The future of humanity and culture

A call to action in bad times

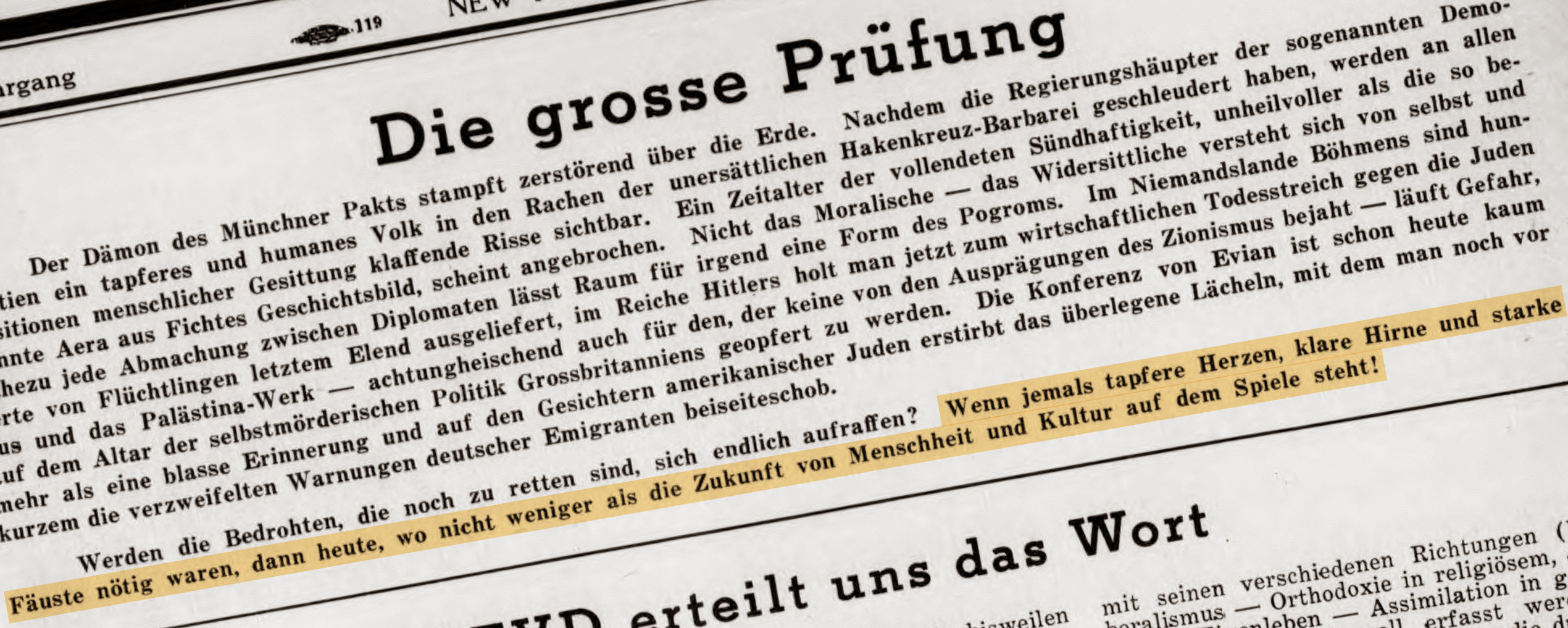

“If ever there was a need for brave hearts, clear minds and strong fists, it is today, as nothing less than the future of humanity and culture is at stake!”

New York

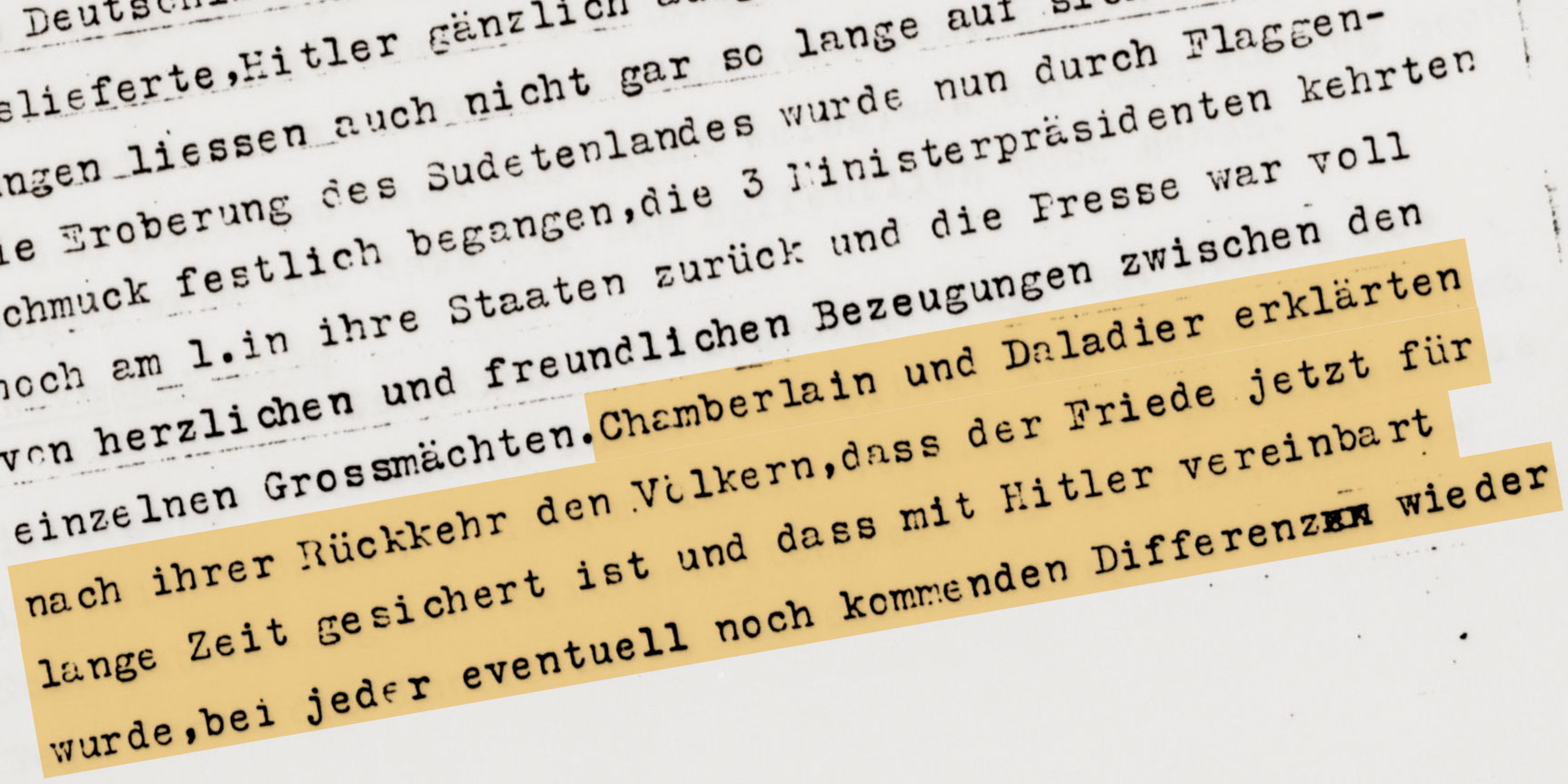

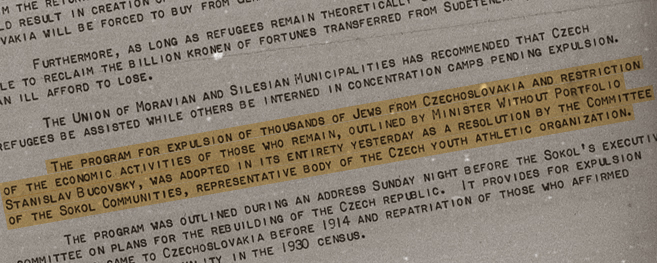

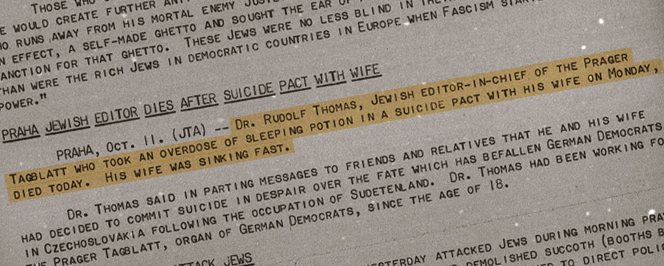

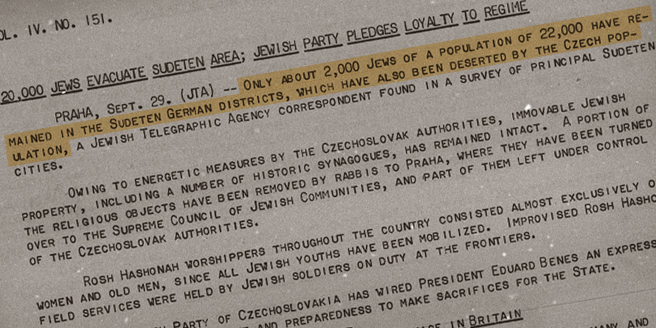

No one reading the November issue of the Aufbau could have missed the front-page editorial message in bold print: under the heading “The Great Trial,” forceful language is employed to decry the abject failure of “the heads of state of the so-called democracies,” who have sacrificed Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany. Jewish refugees are left stranded in no man’s land in Bohemia, in Germany, the Nazis are dealing an “economic death blow” to the Jews, the British are jeopardizing the Zionist project, and “little more than a faint memory” remains of the Evian Conference, summoned in July to tackle the problem of resettling Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. Surely, this is “an era of complete sinfulness.” Will those under threat finally brace up?

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

"Die große Prüfung," Editorial, Aufbau, Vol. 4, No. 12, p. 1