Not the country of her dreams

Emigrants don't get to choose

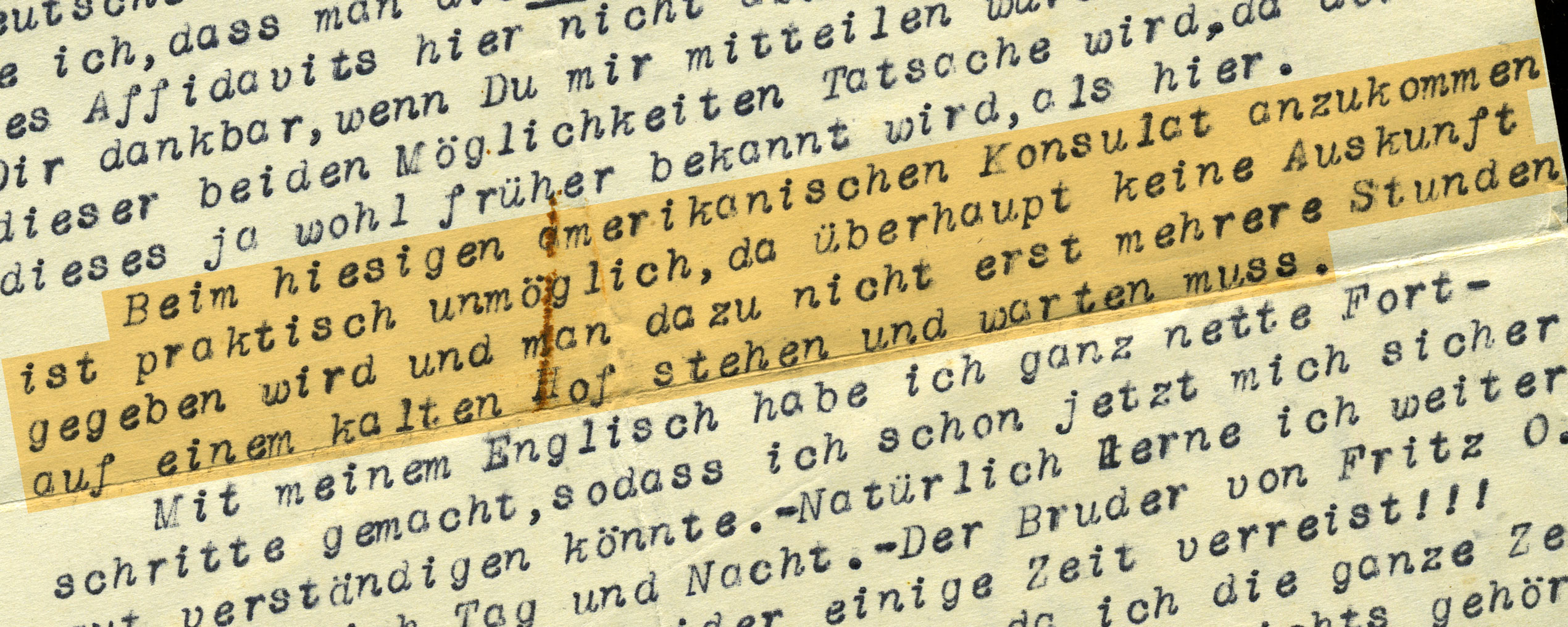

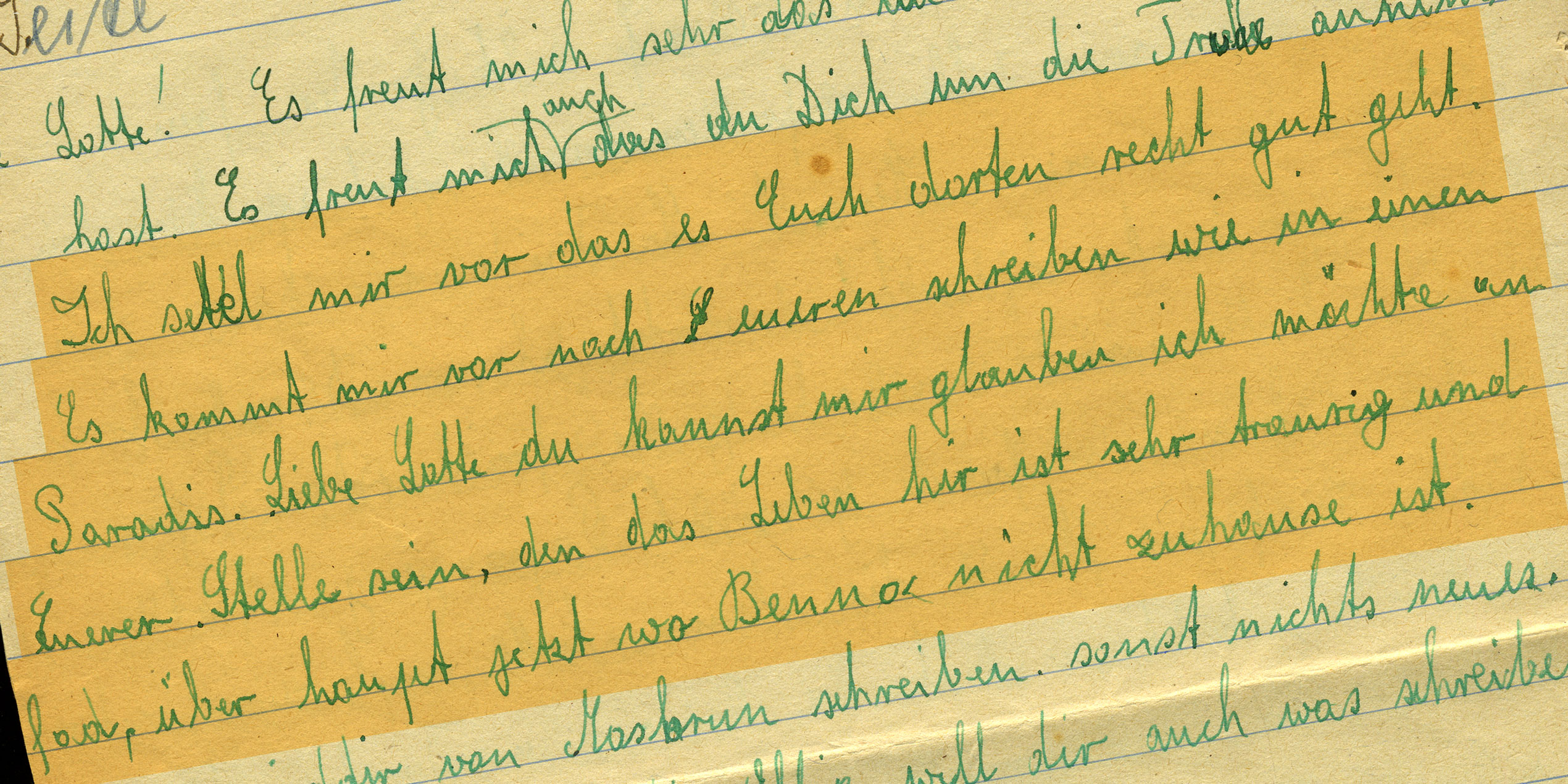

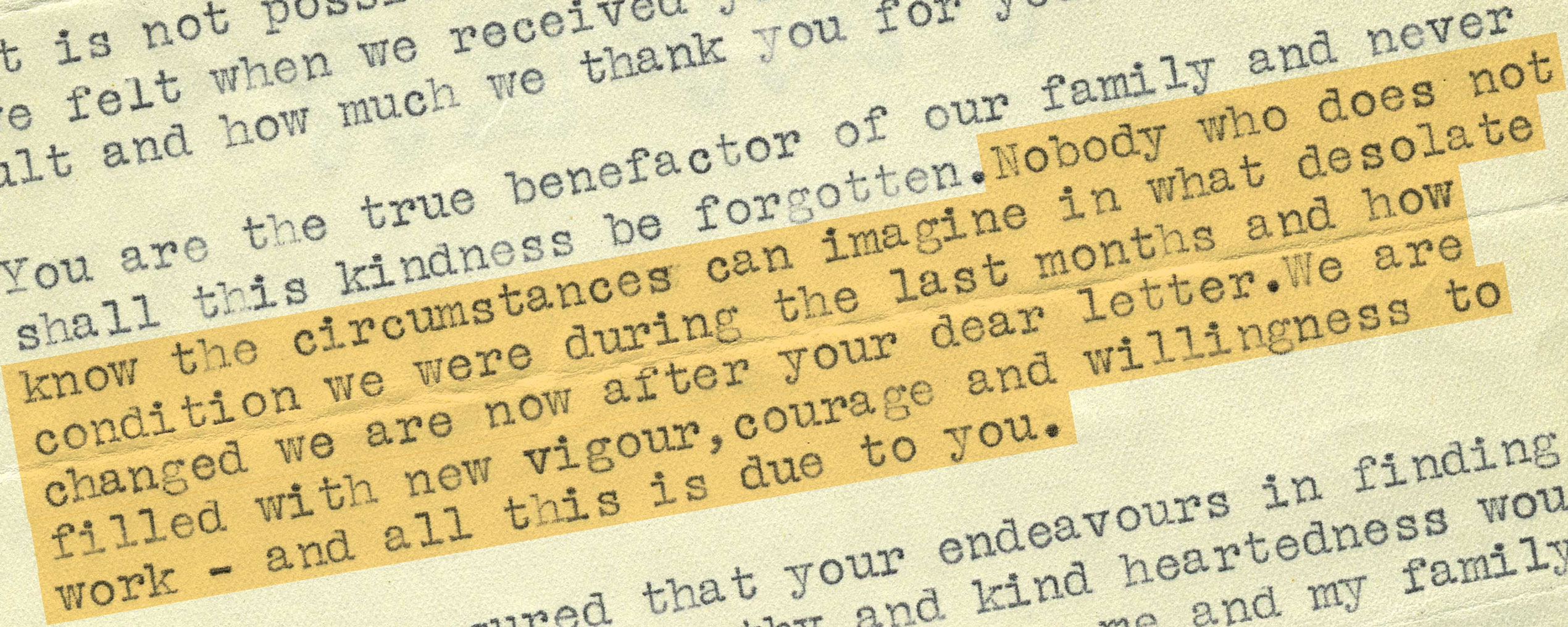

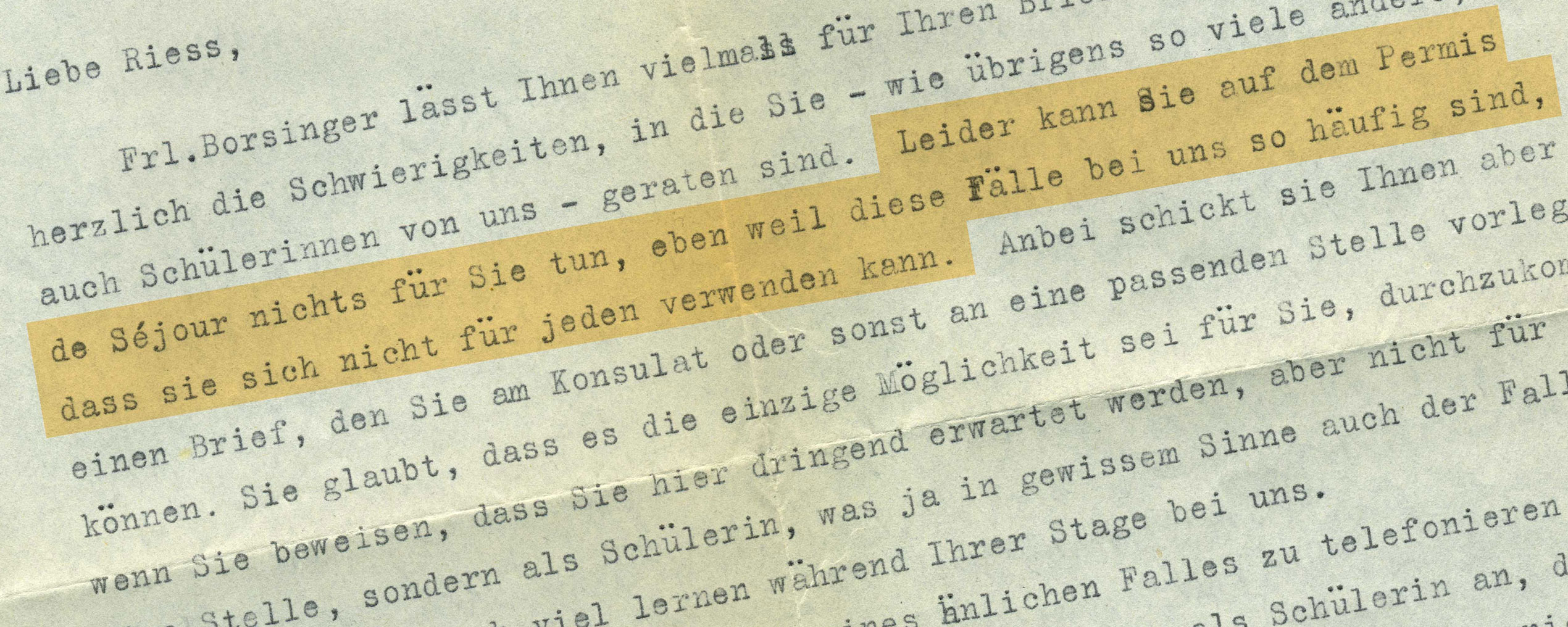

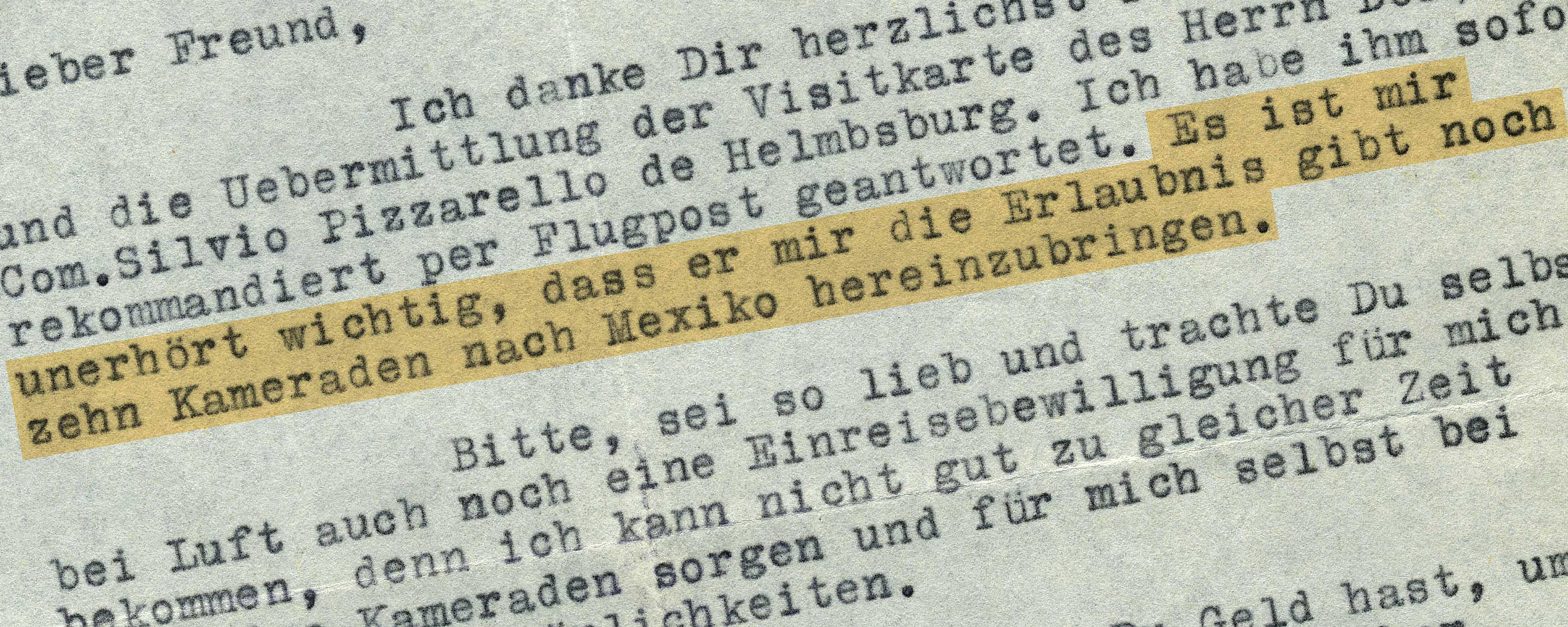

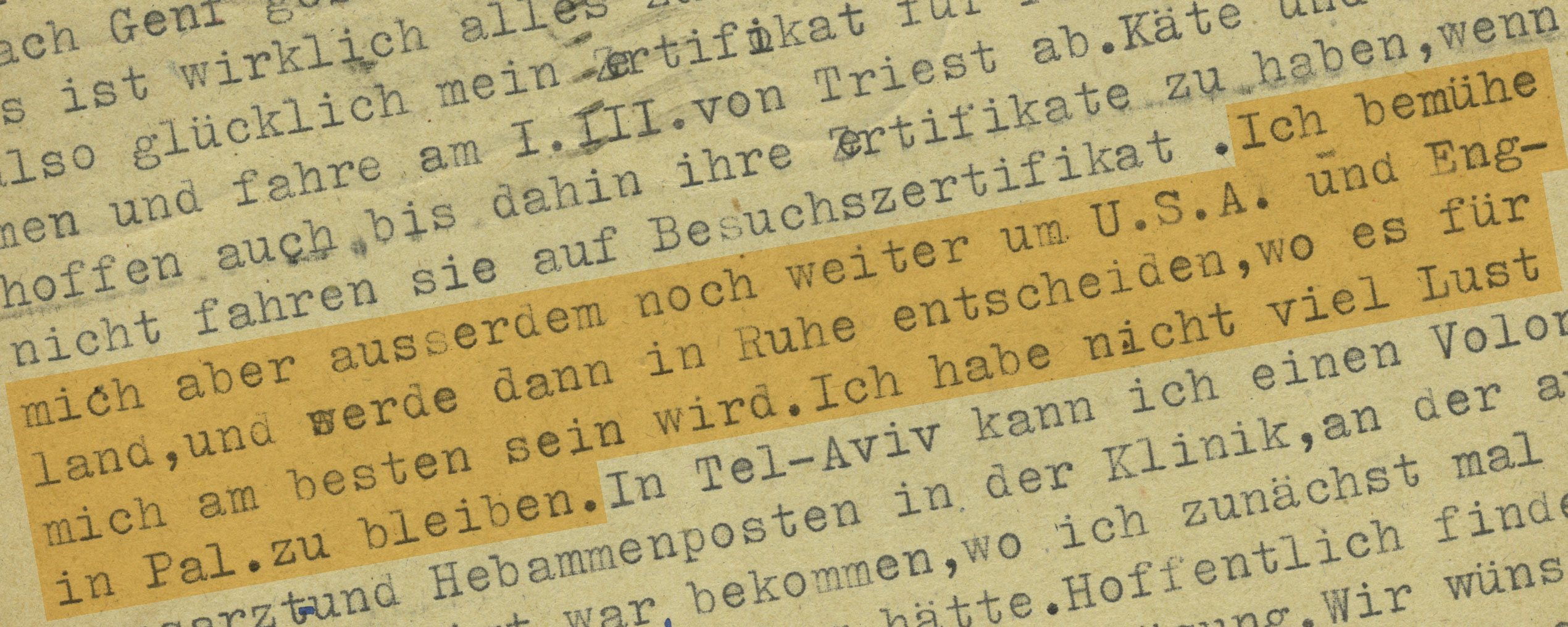

“What's more, I'm actually still trying for the US and England and then, in peace and comfort, will decide where will be best for me. I'm not very eager to stay in Pal[estine].”

Siena/Turin

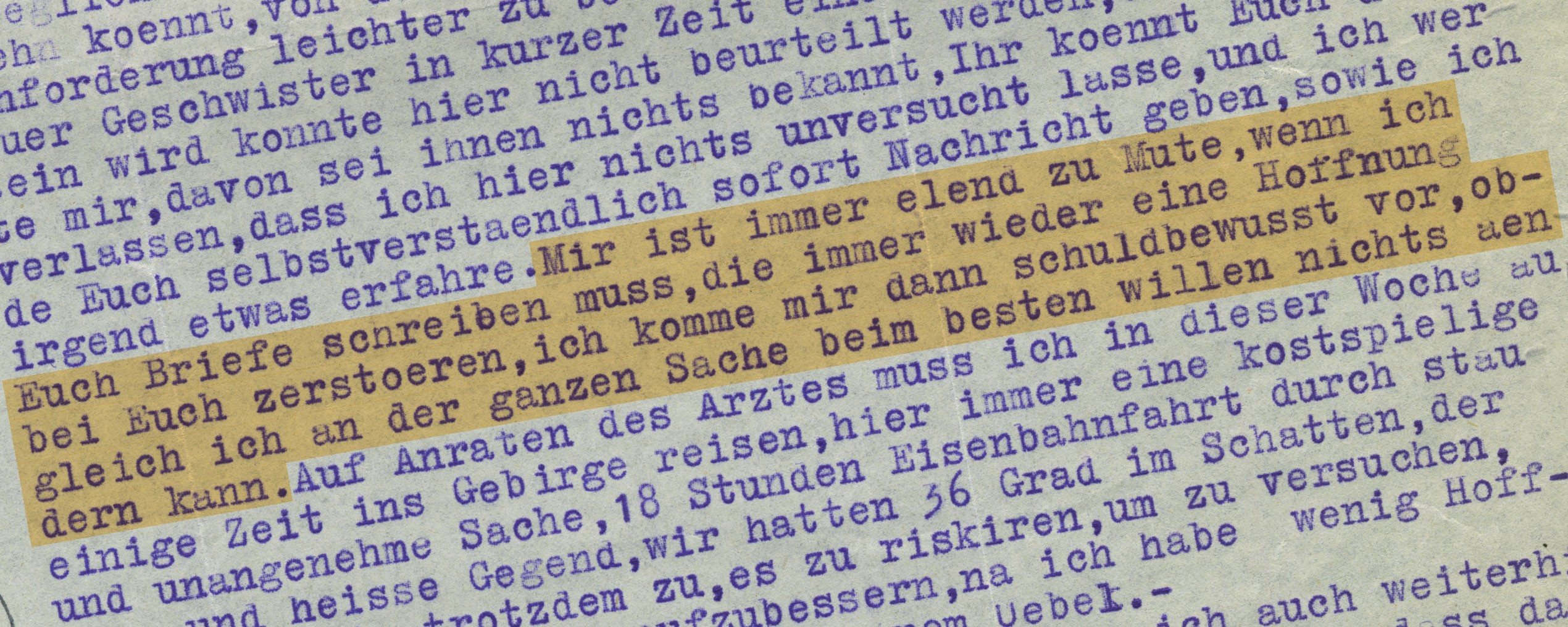

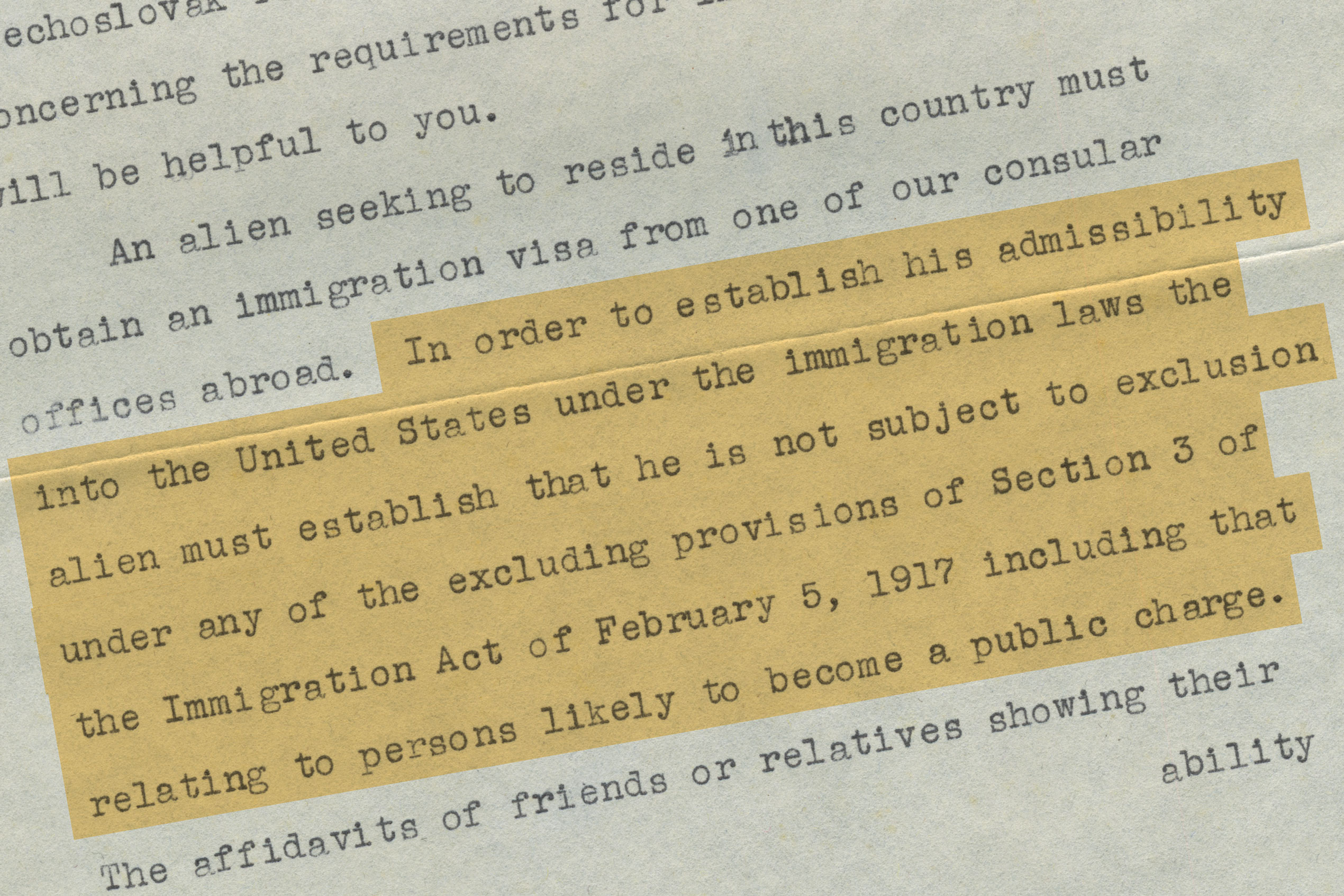

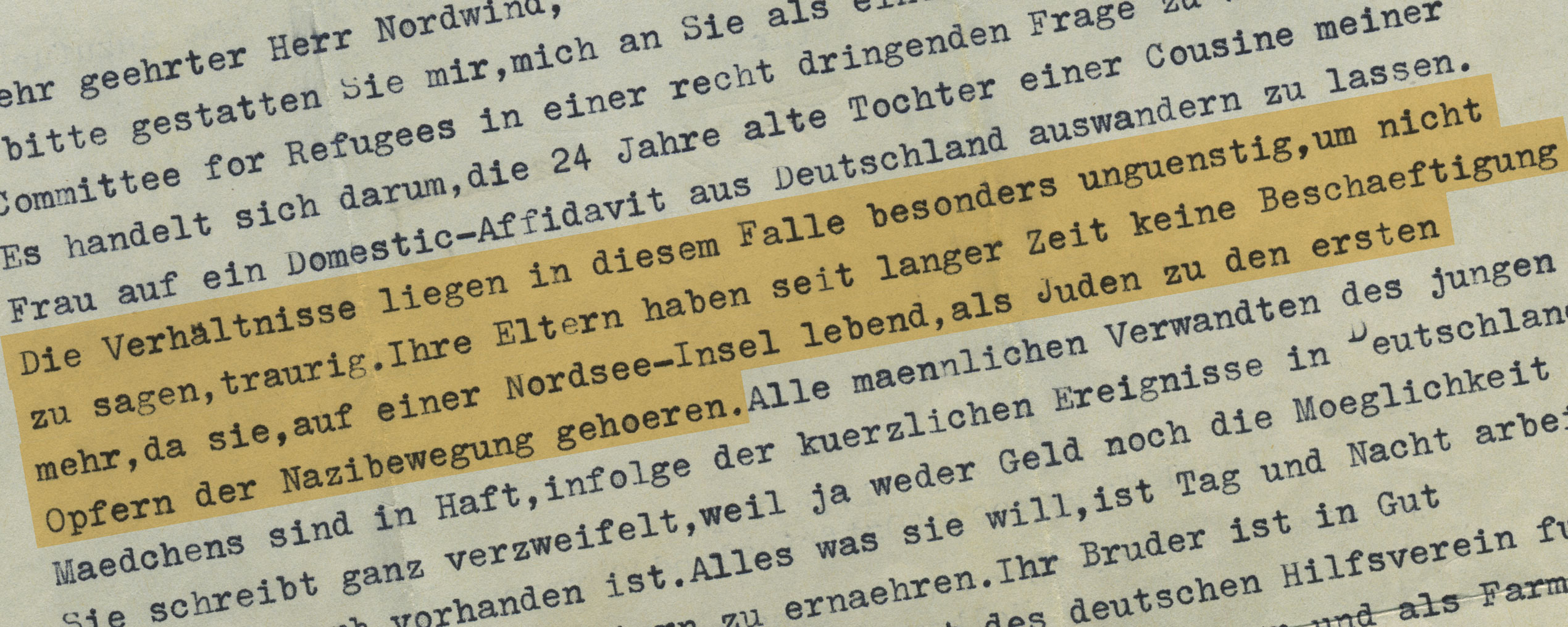

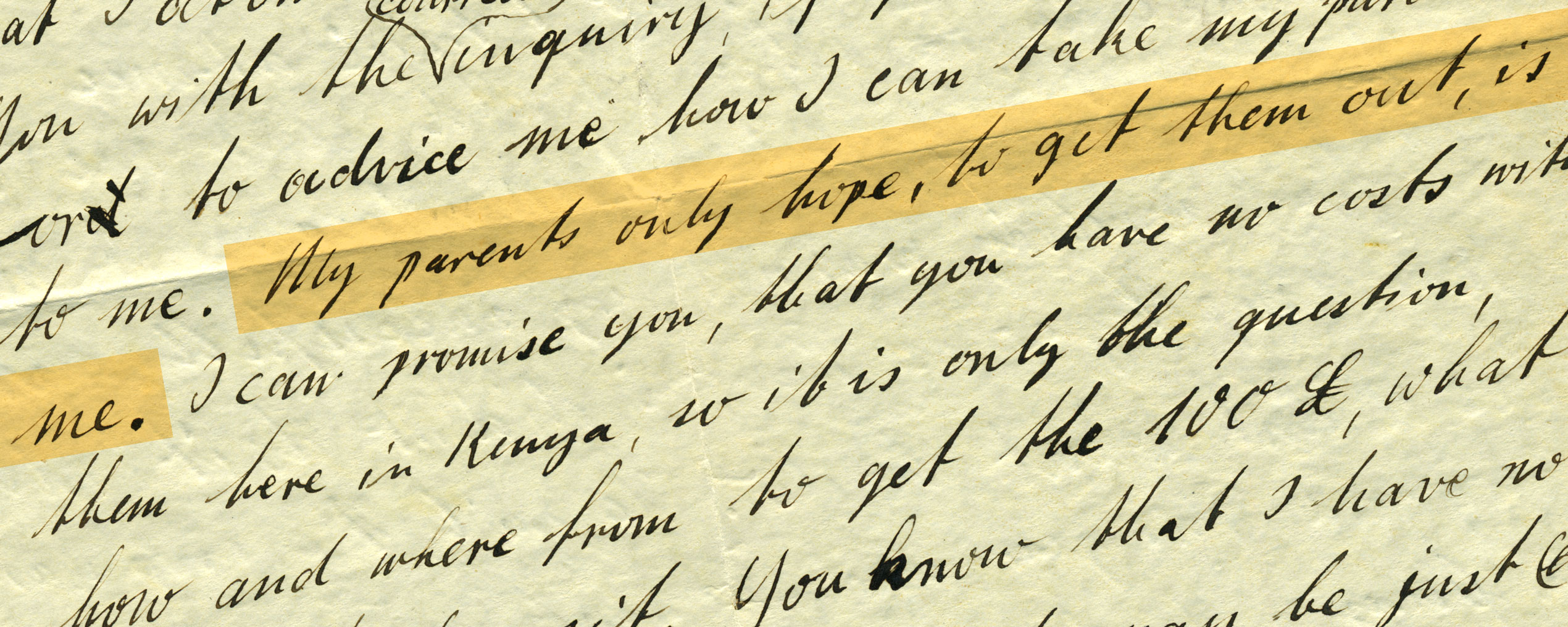

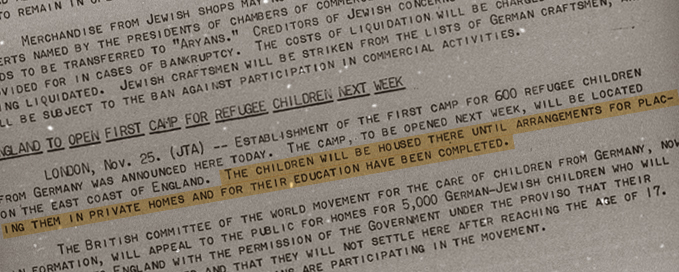

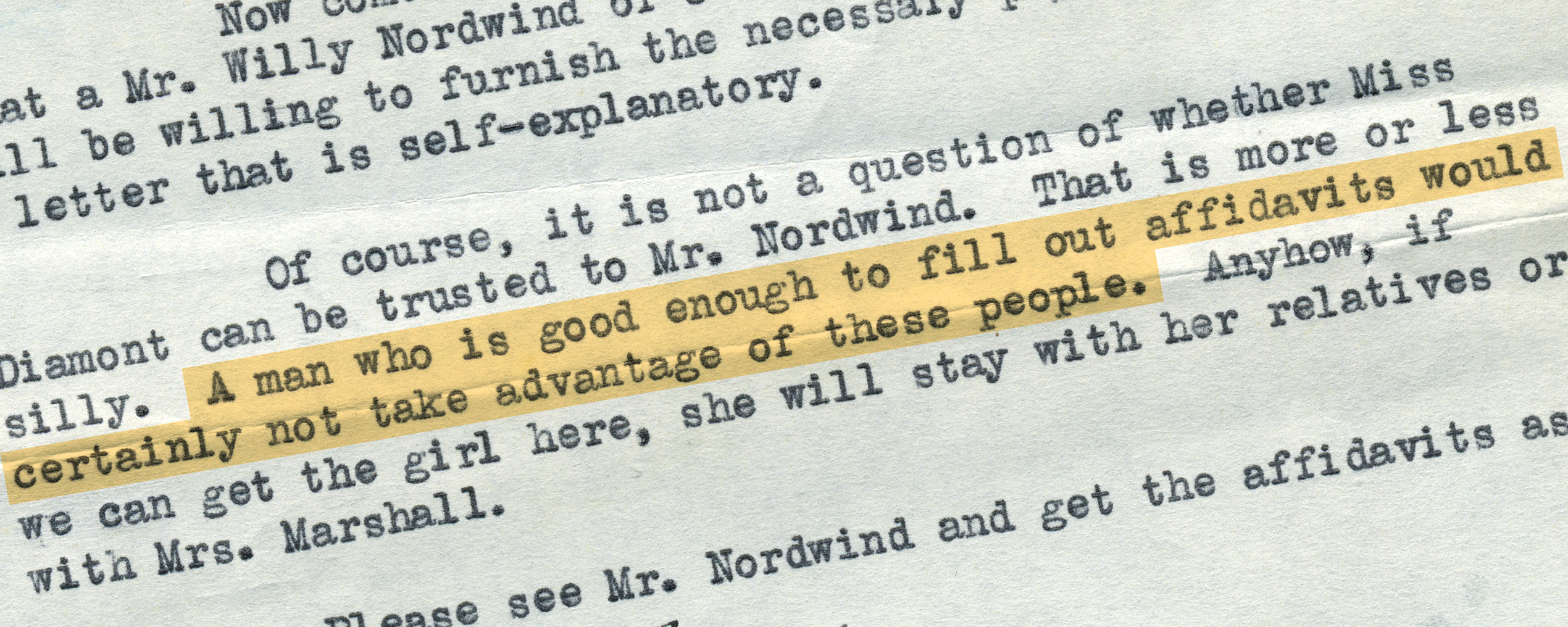

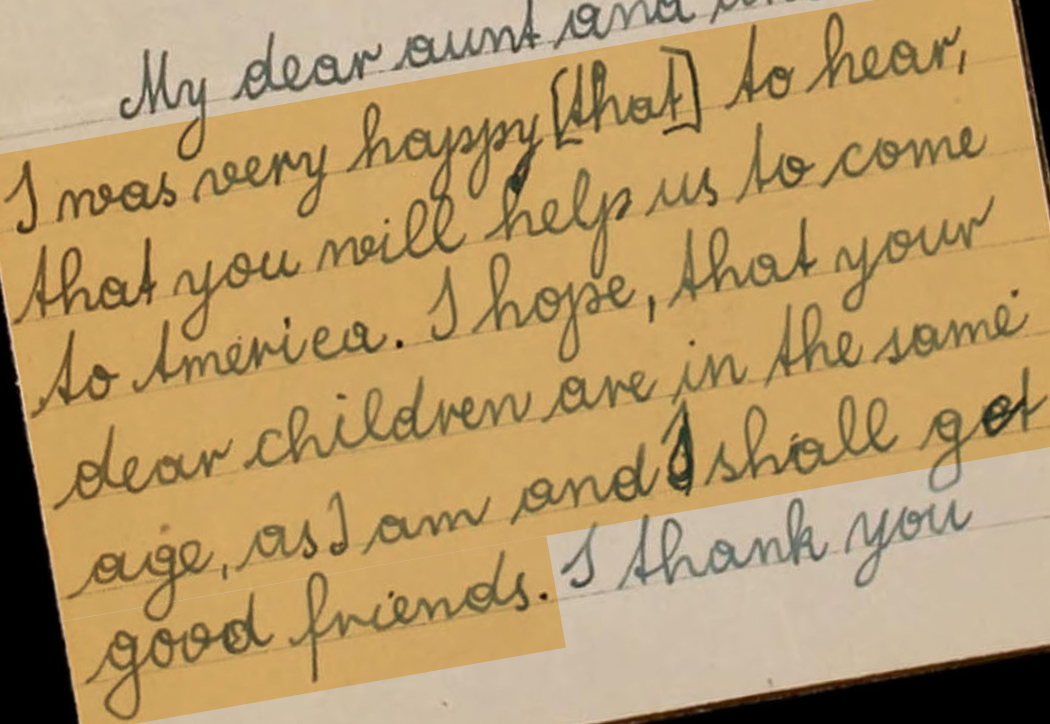

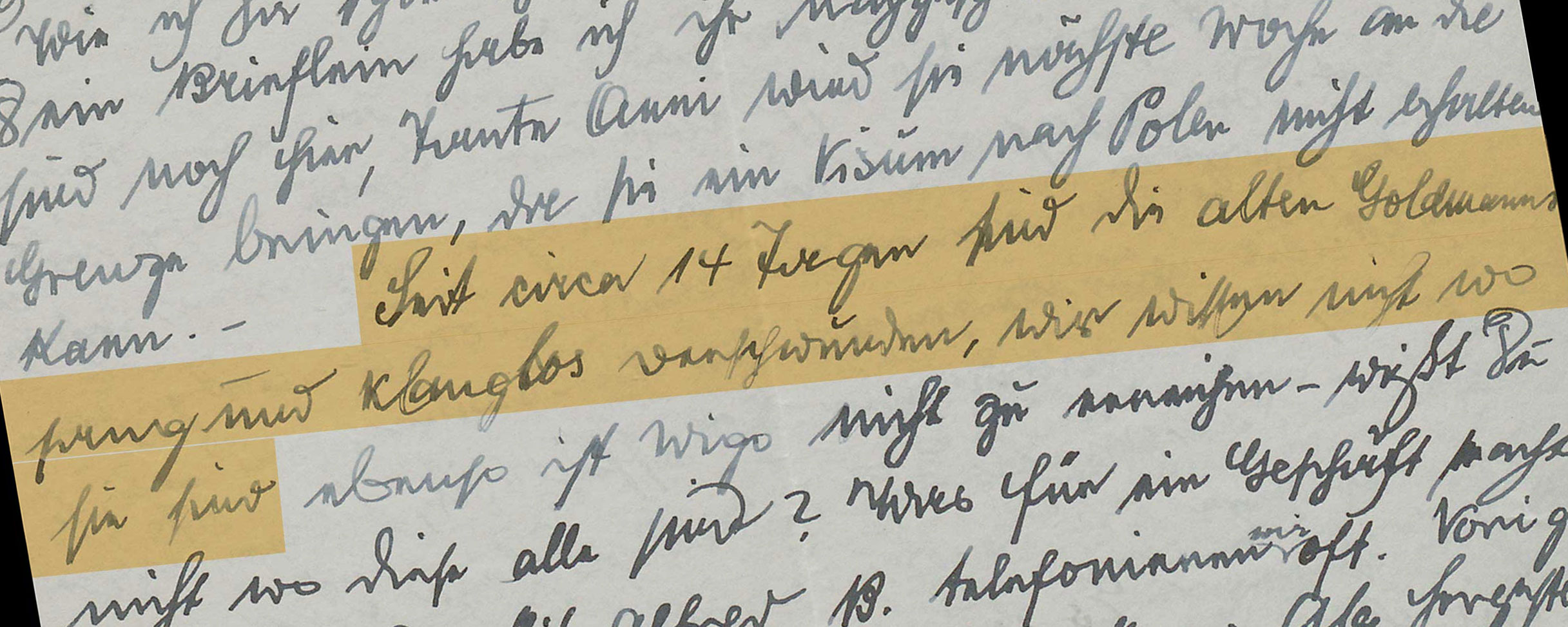

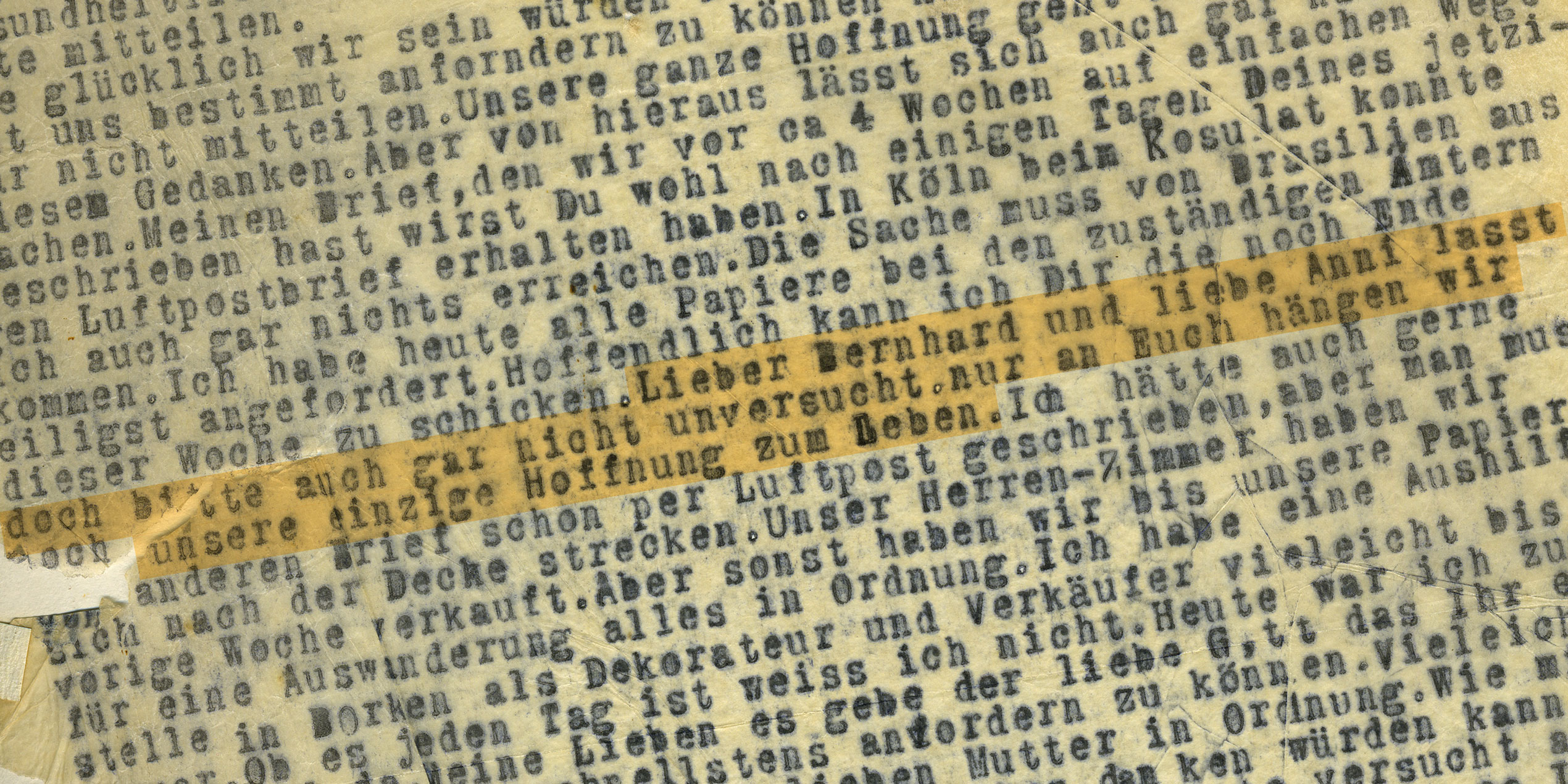

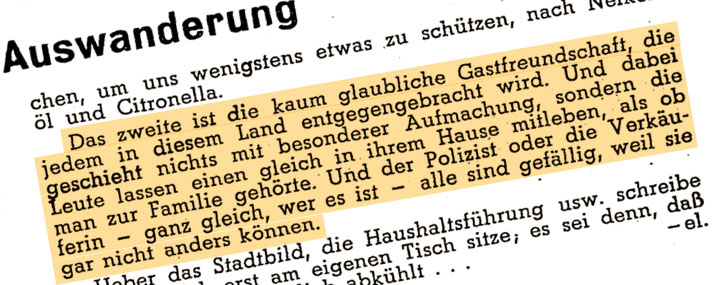

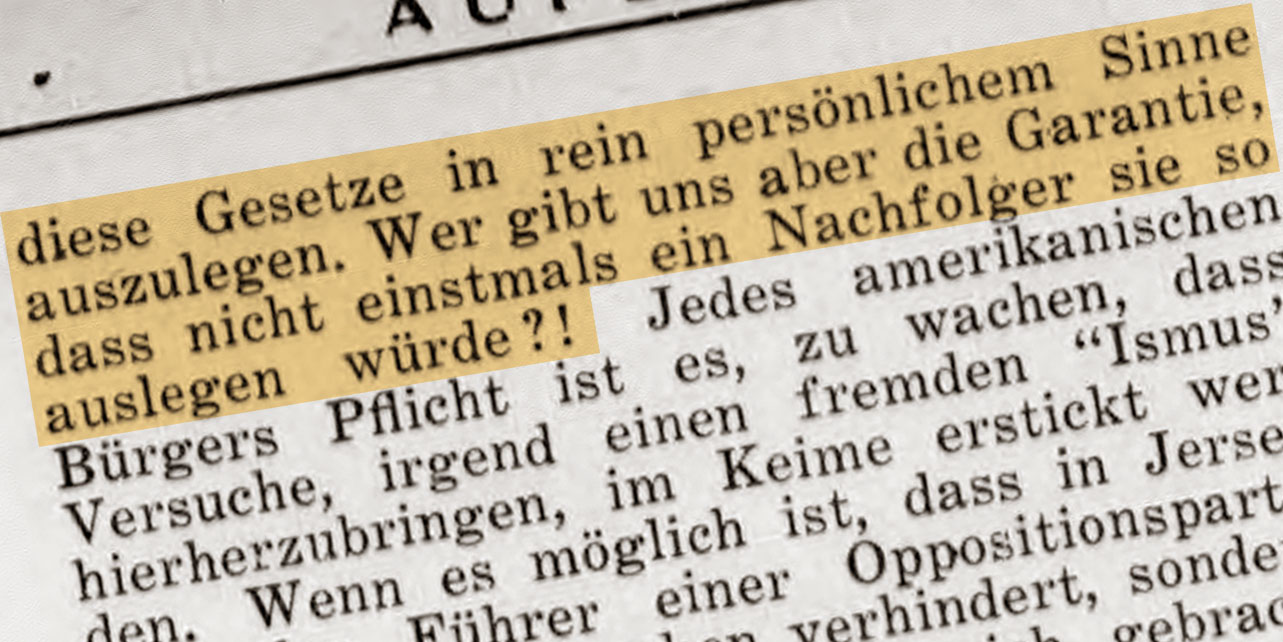

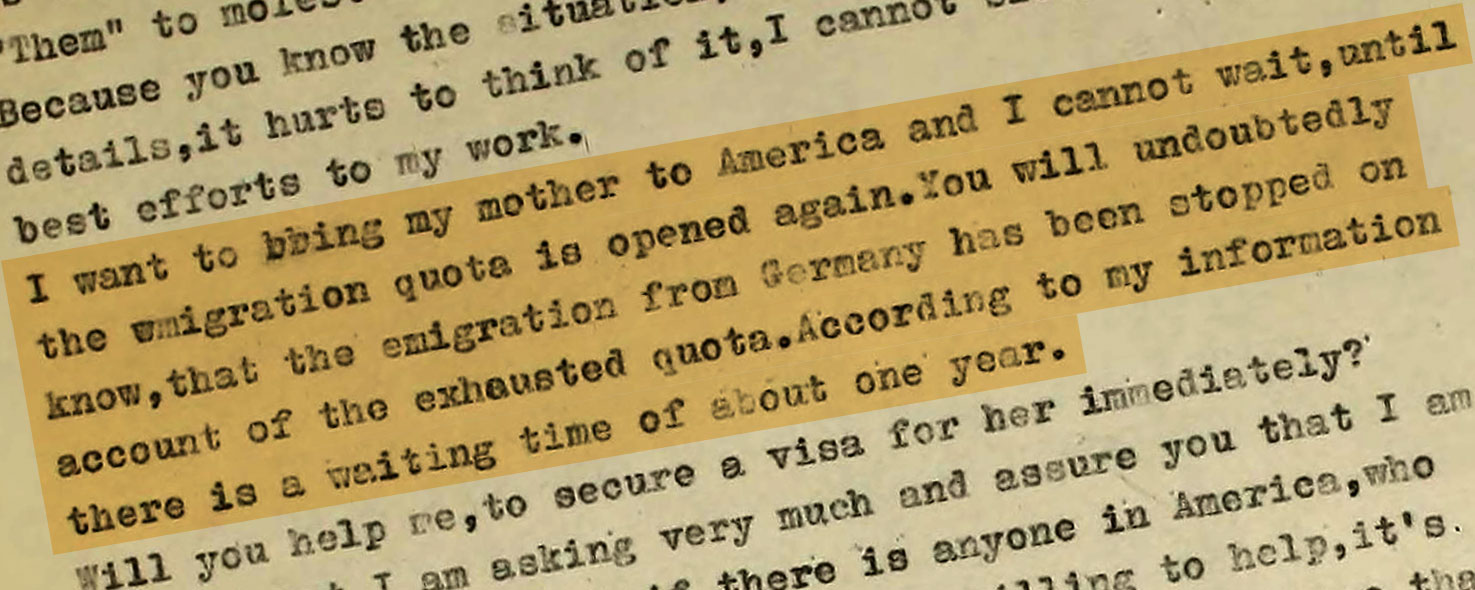

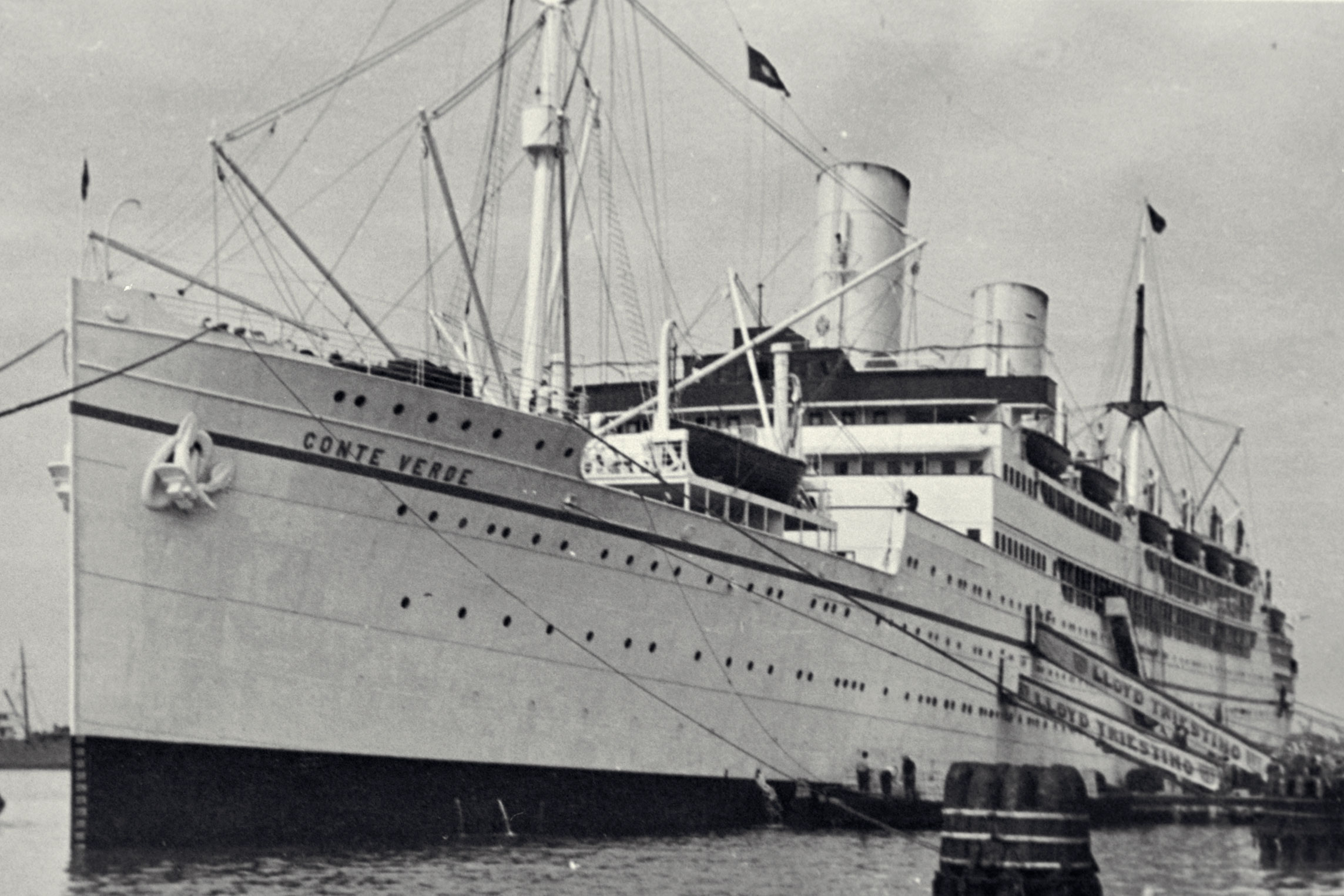

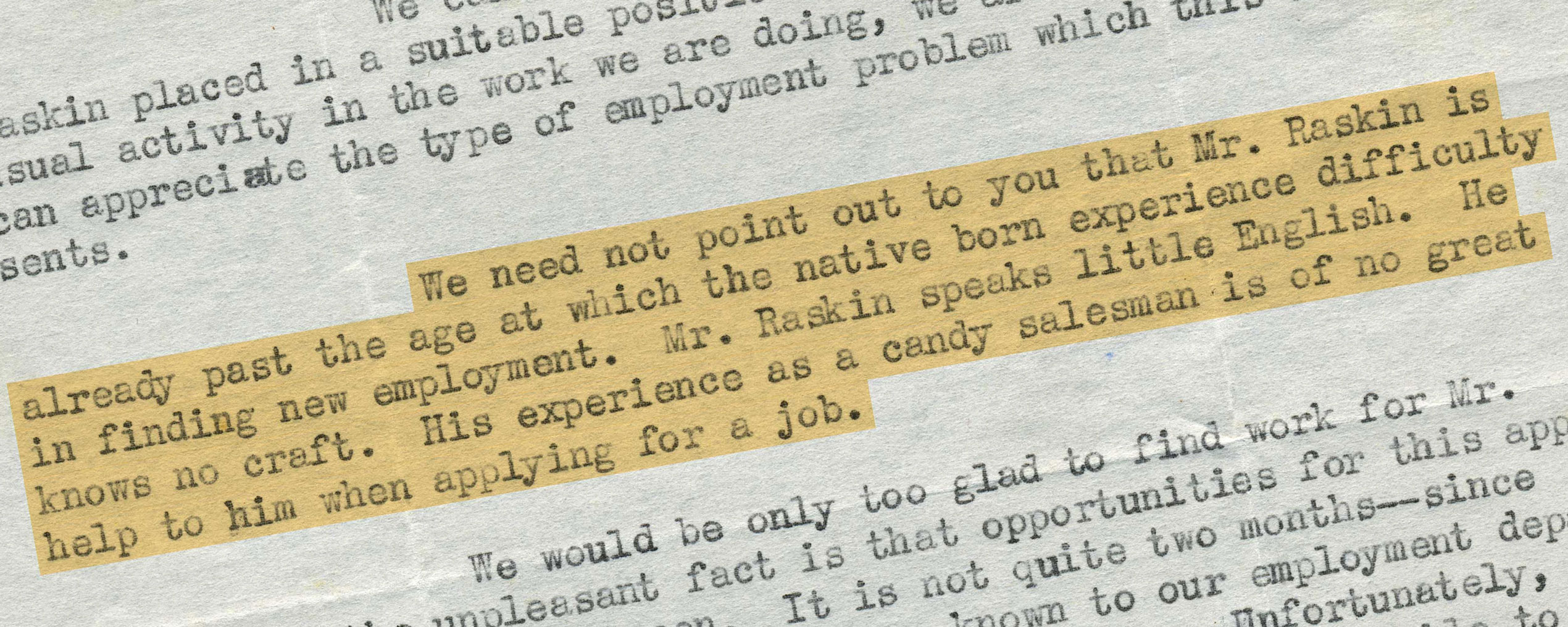

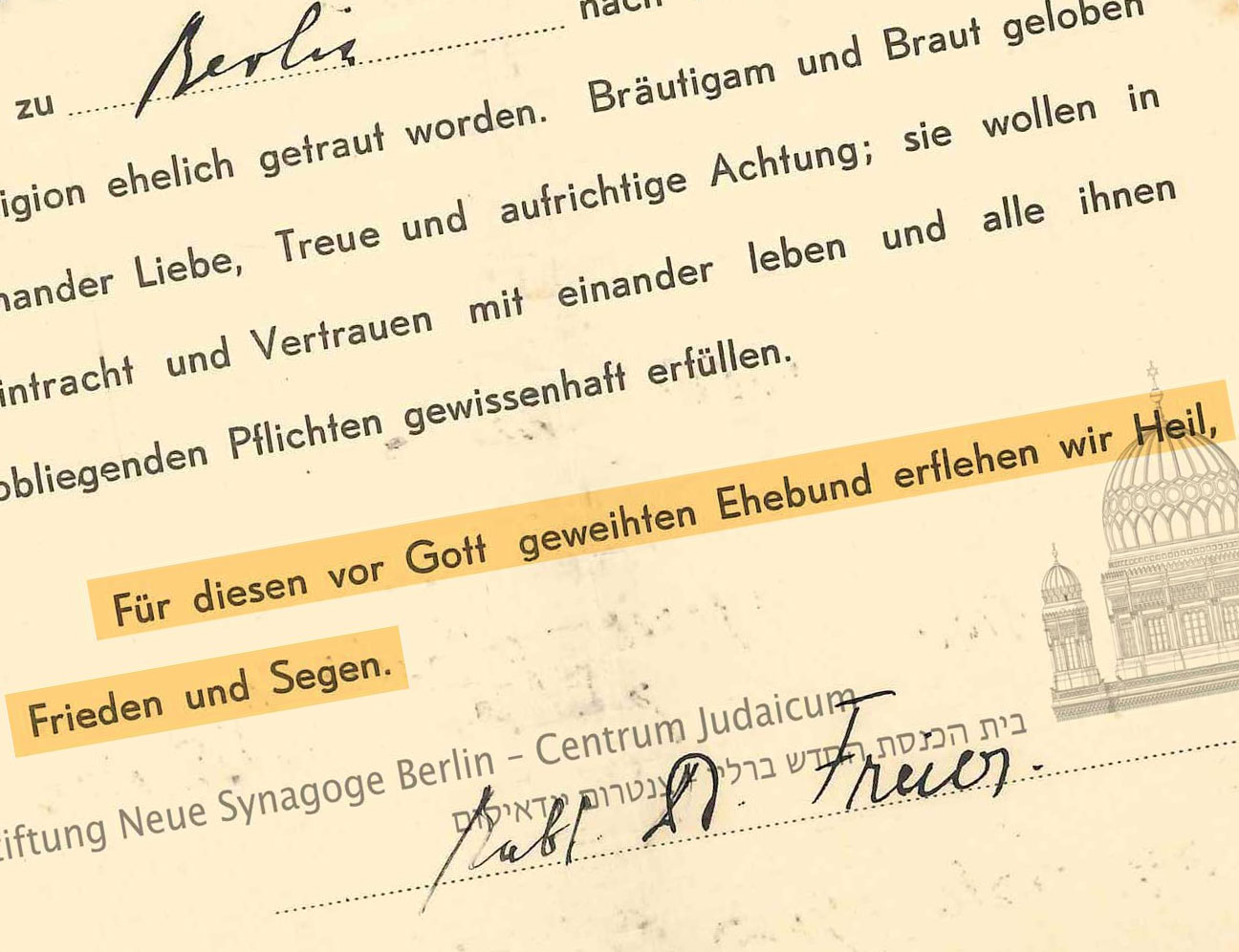

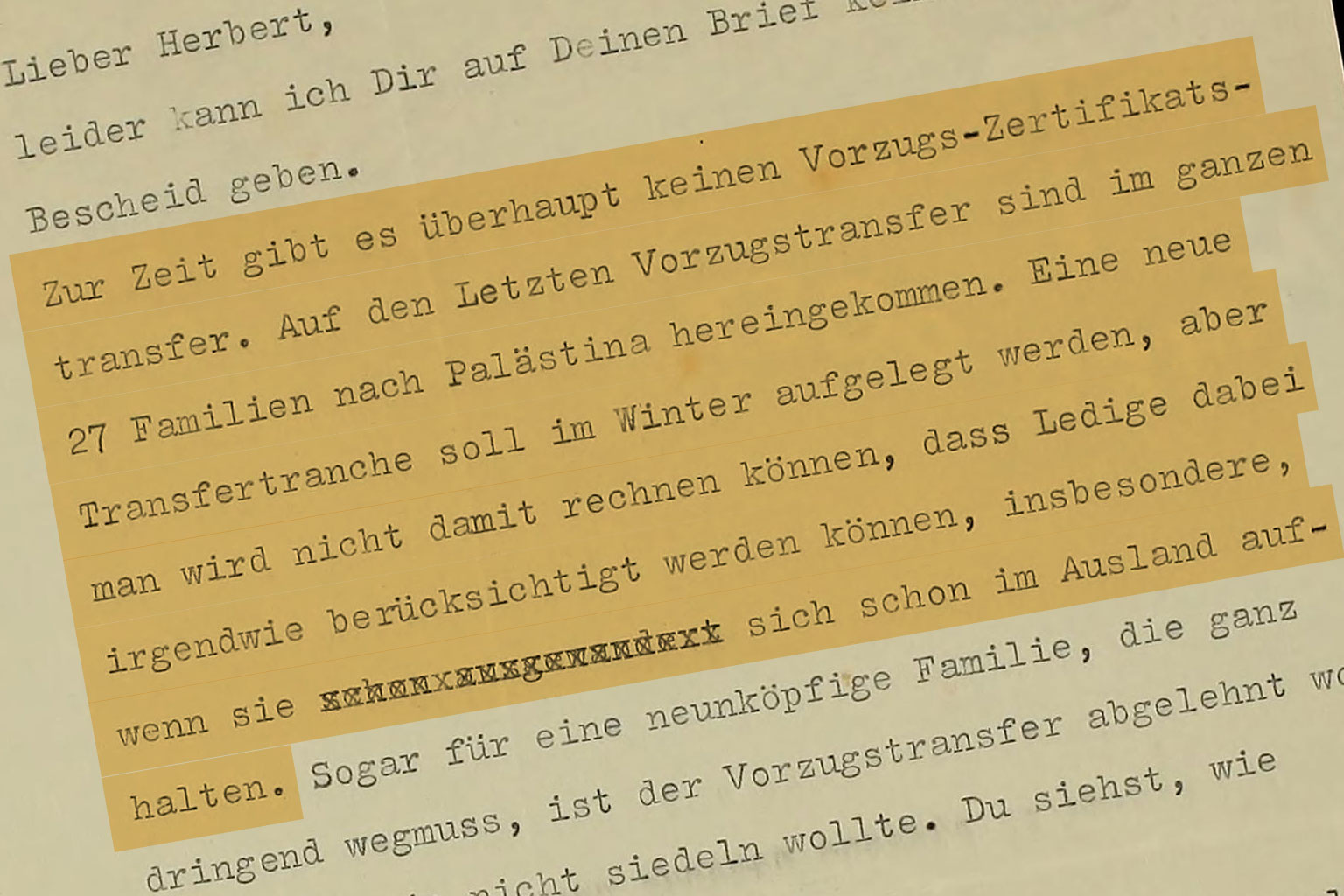

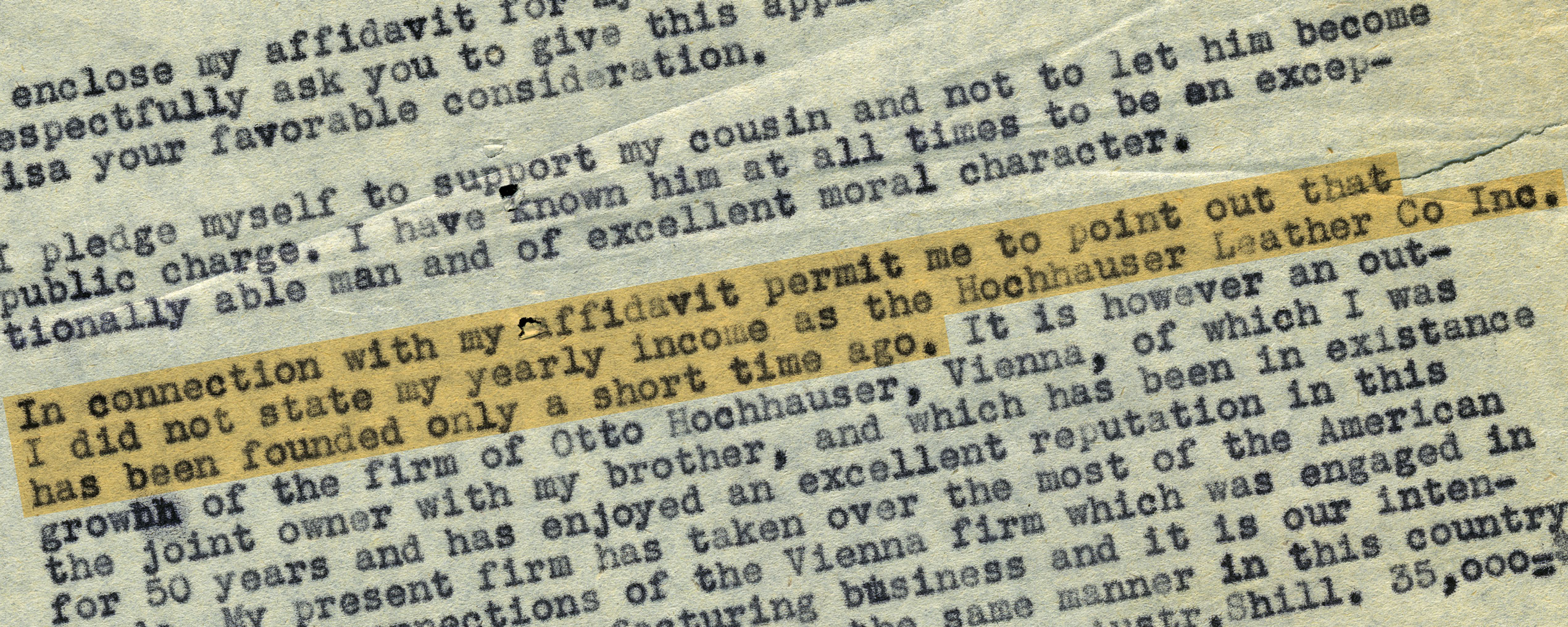

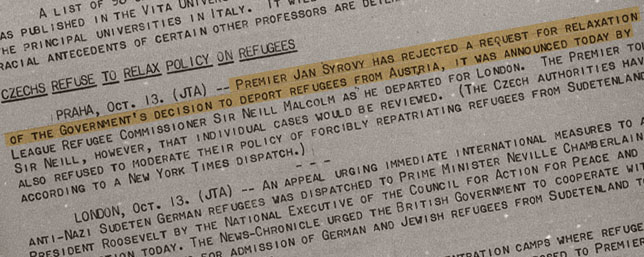

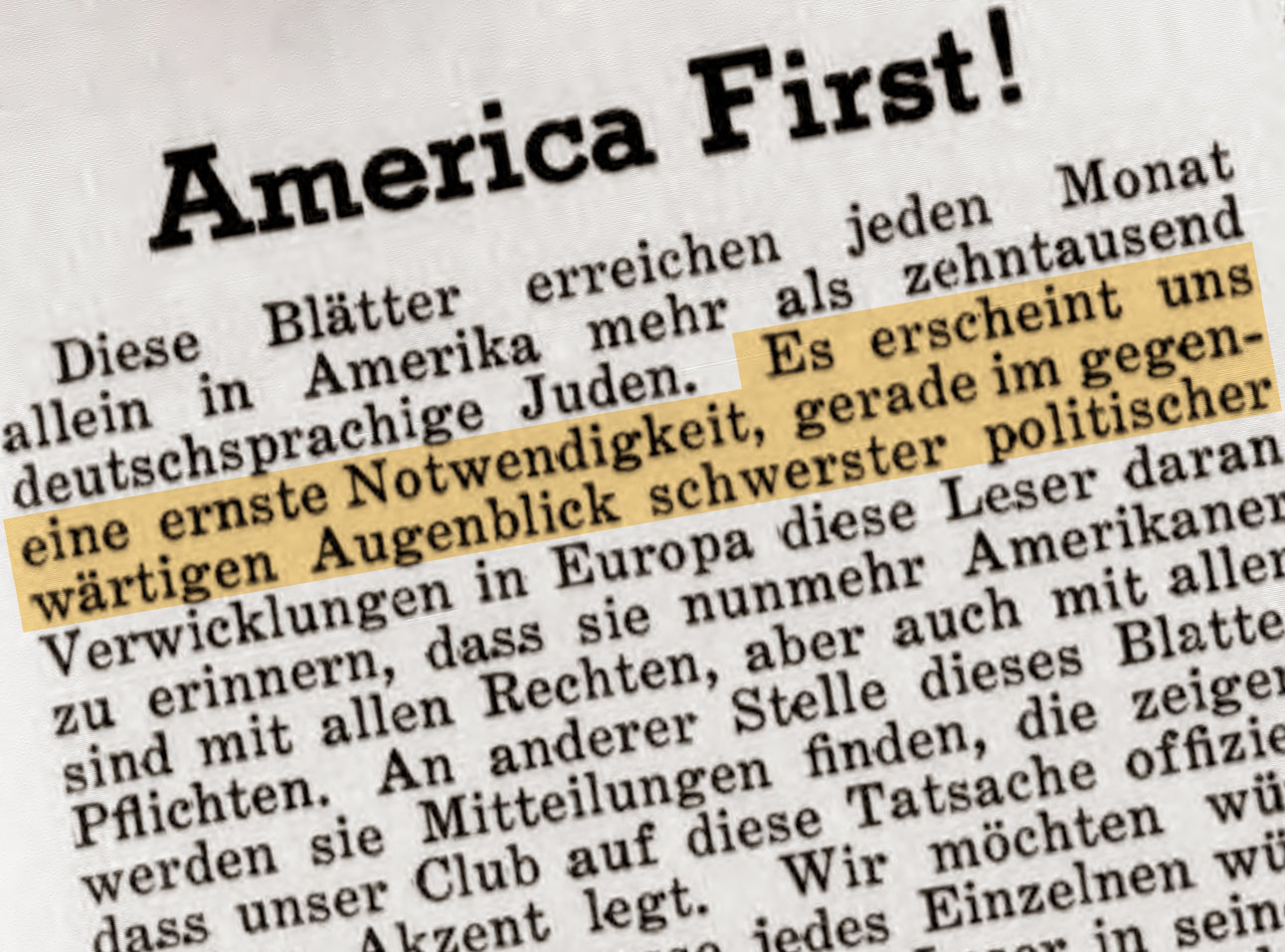

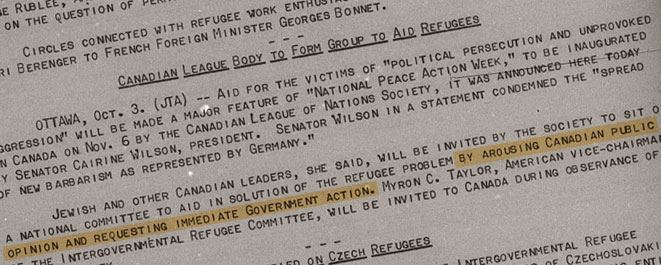

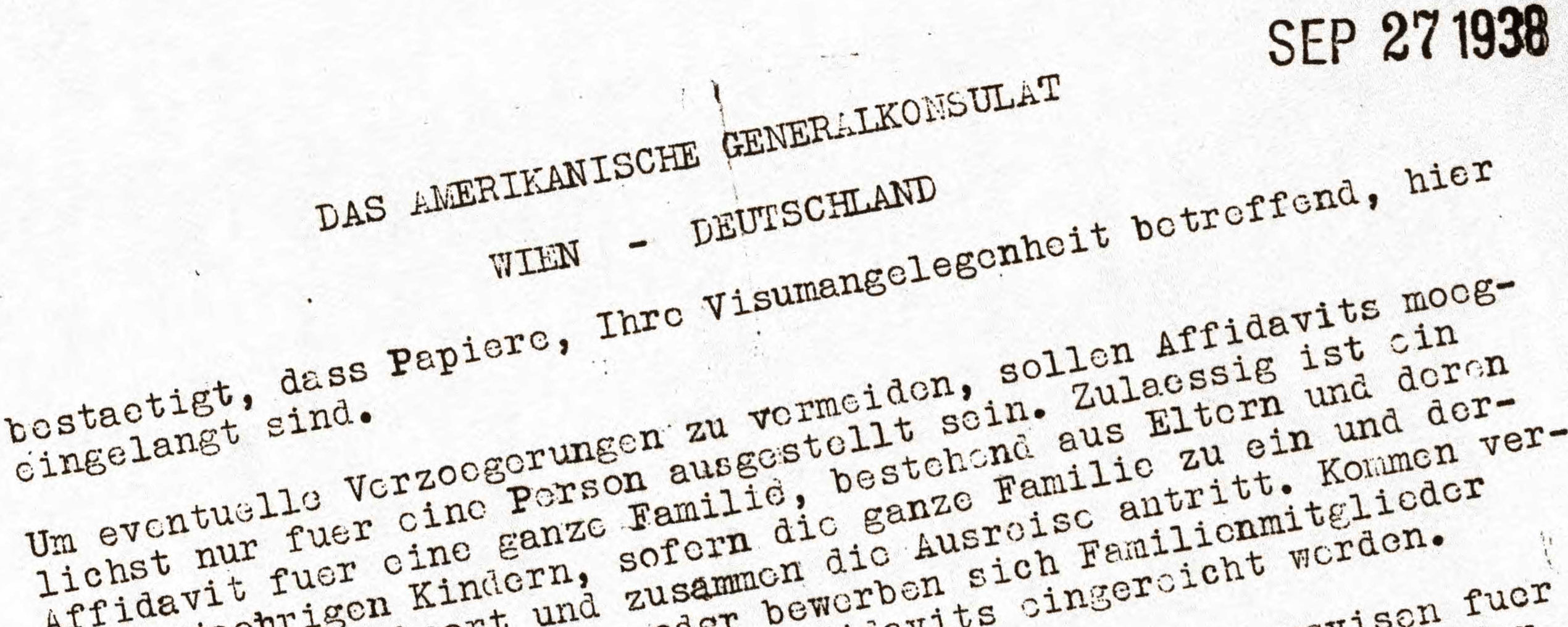

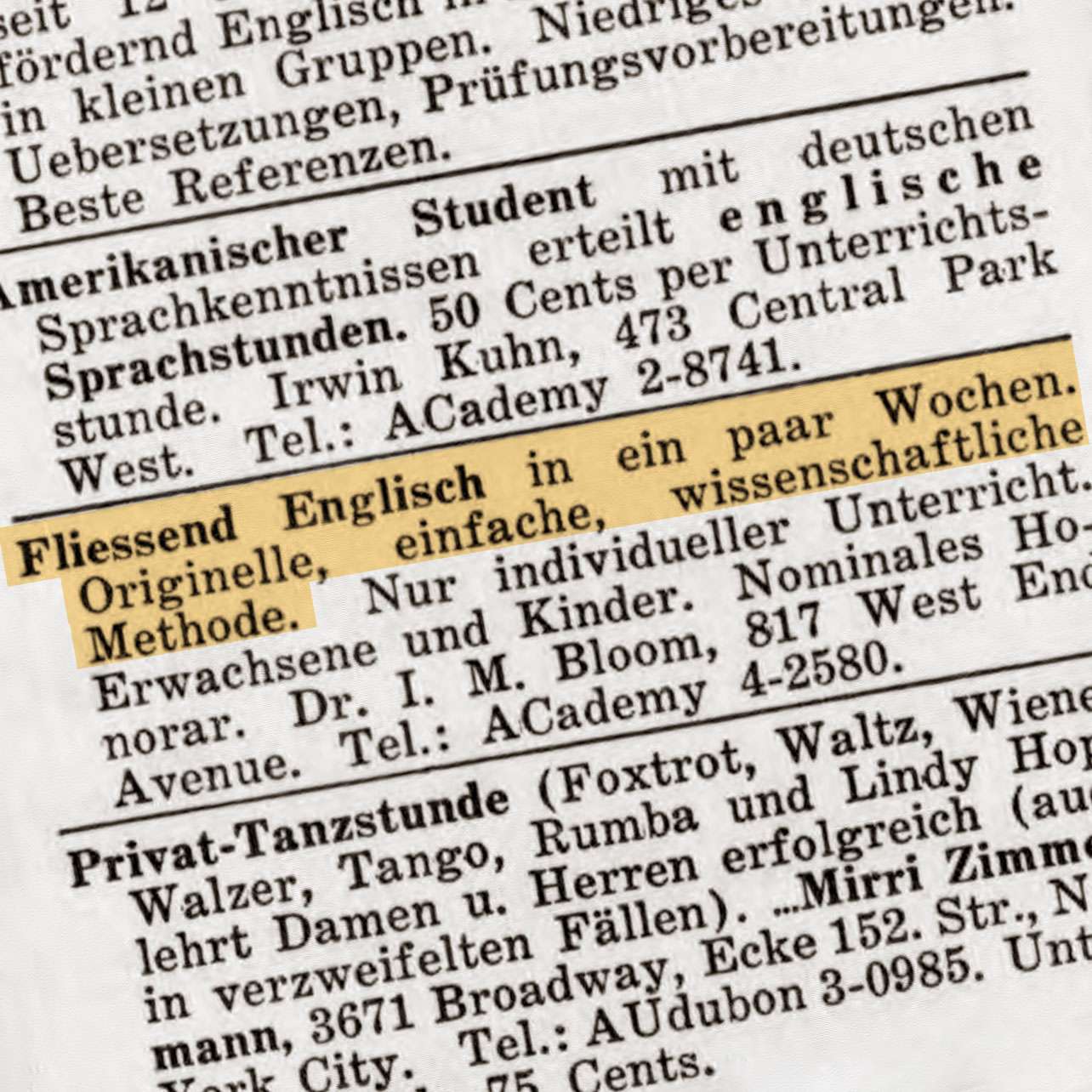

Stella was not thrilled about the idea of living in Palestine. Like her friend, Annemarie Riess, with whom she shared her feelings on December 28th, she had fled to Italy. But as a Jew, she was no longer welcome there, either. According to the fascist regime’s new racial laws, non-native Jews were to leave the country within six months. 2,000 of the 10,000 foreign Jews who had settled down in Italy before 1919 were exempt from the provision. At least Stella had an immigration certificate for Palestine, issued by the Mandatory Government, and at a Tel Aviv clinic, an unpaid position that came with free room and board was waiting for her. Nevertheless, she continued to try to get permission to enter the US or England. Actually, even the offer on an unpaid position was more than many immigrant physicians could expect in Palestine. Since 1936, there was a surplus of physicians in the land, and a new wave of immigration after the annexation of Austria in February 1938 (“Anschluss”) had aggravated the situation even more.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Anneliese Riess Collection, AR 10019

Original:

Box 1, folder 10