Evicted

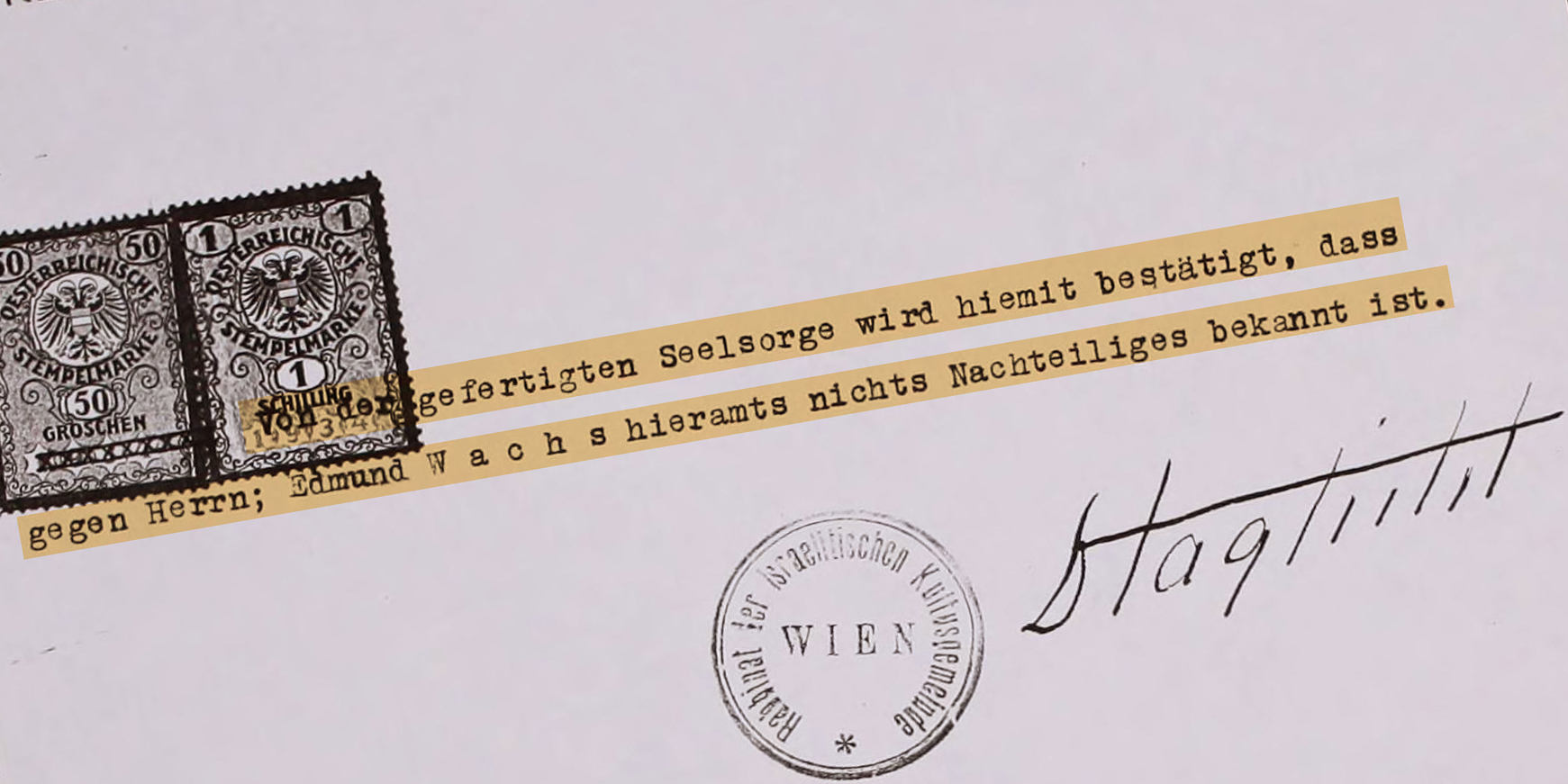

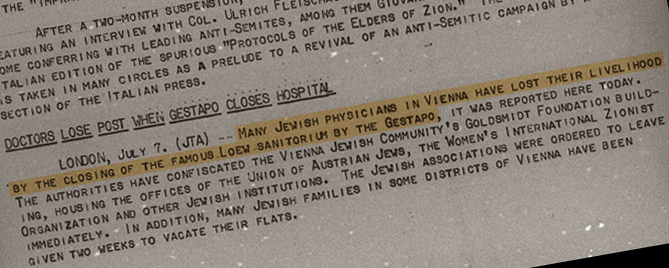

Housing woes reach Jews in Vienna

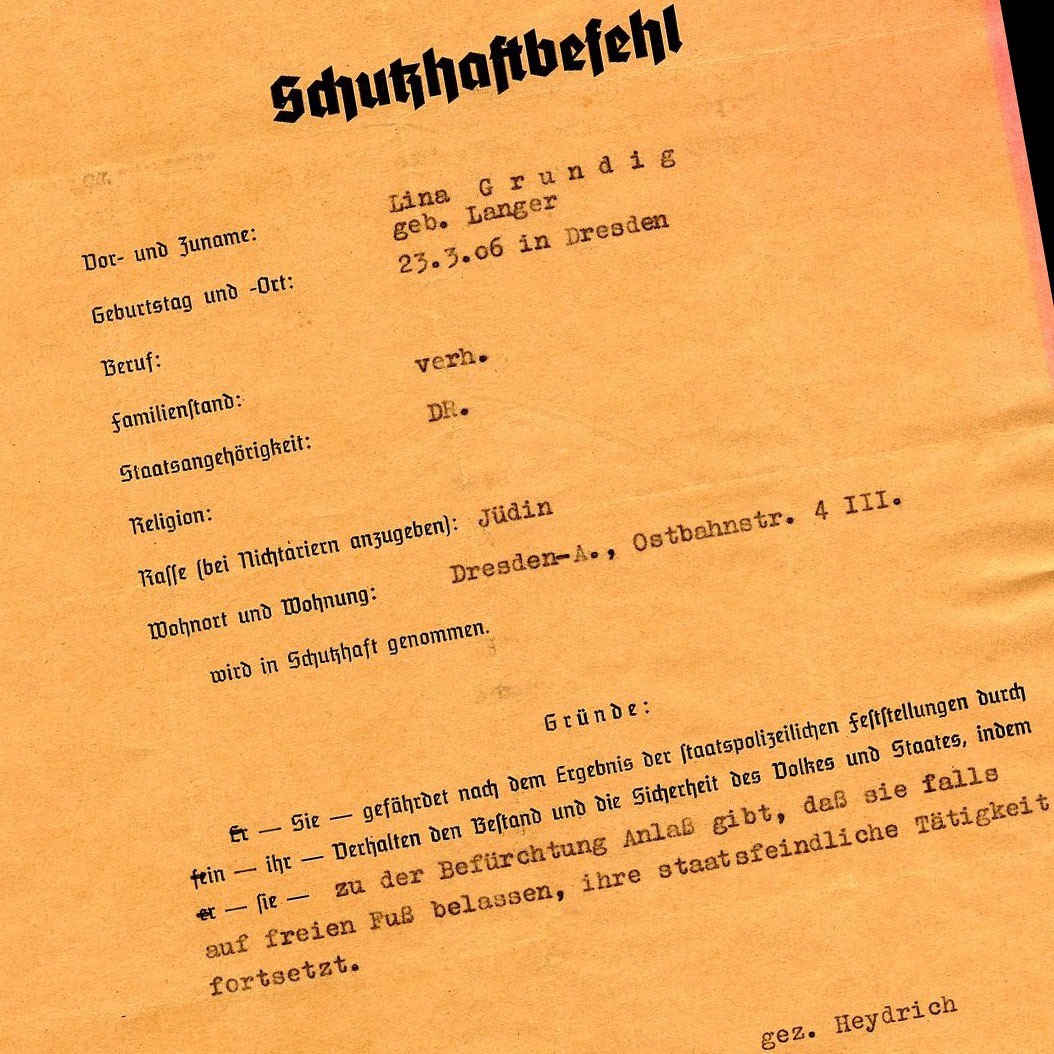

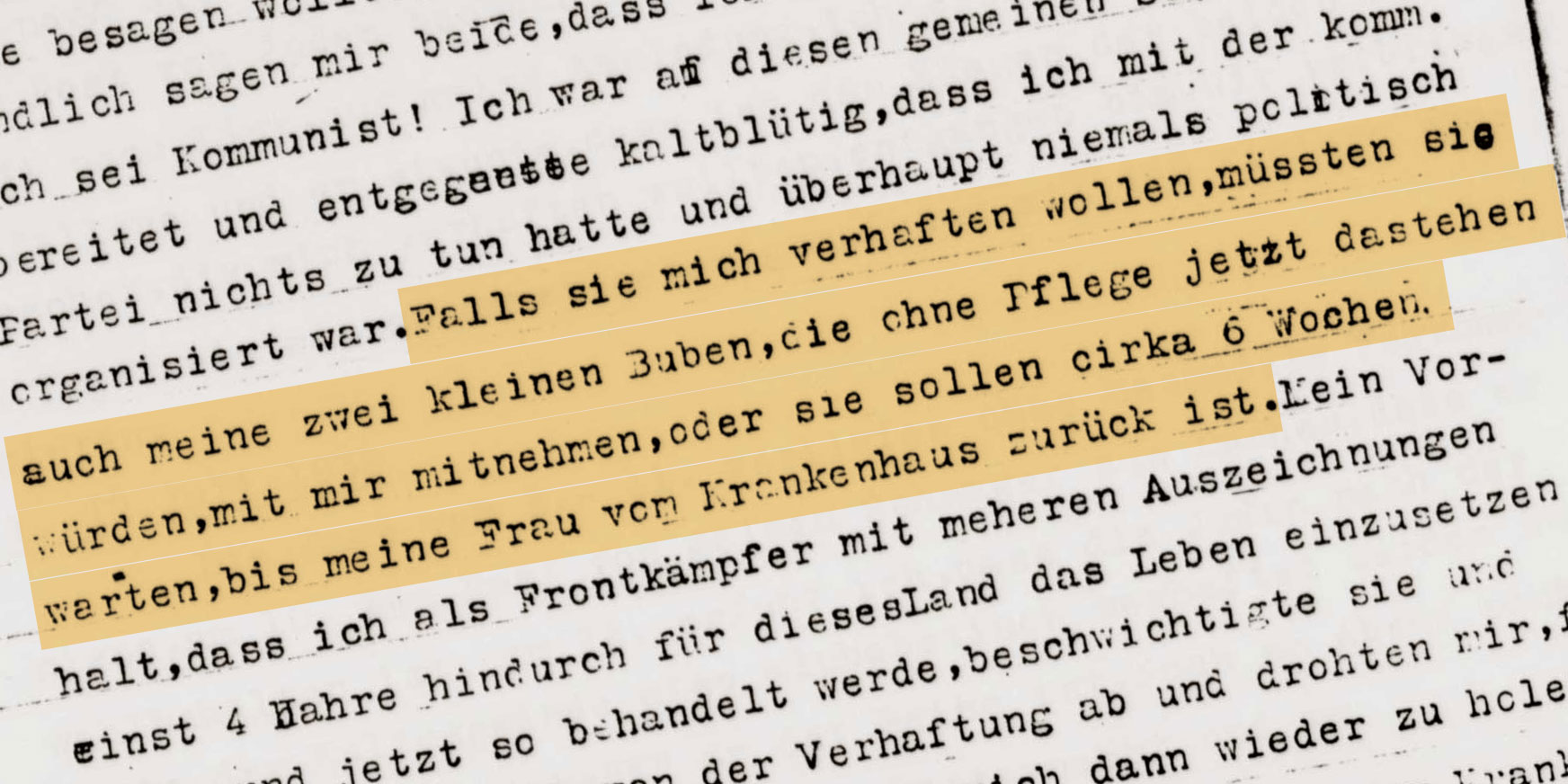

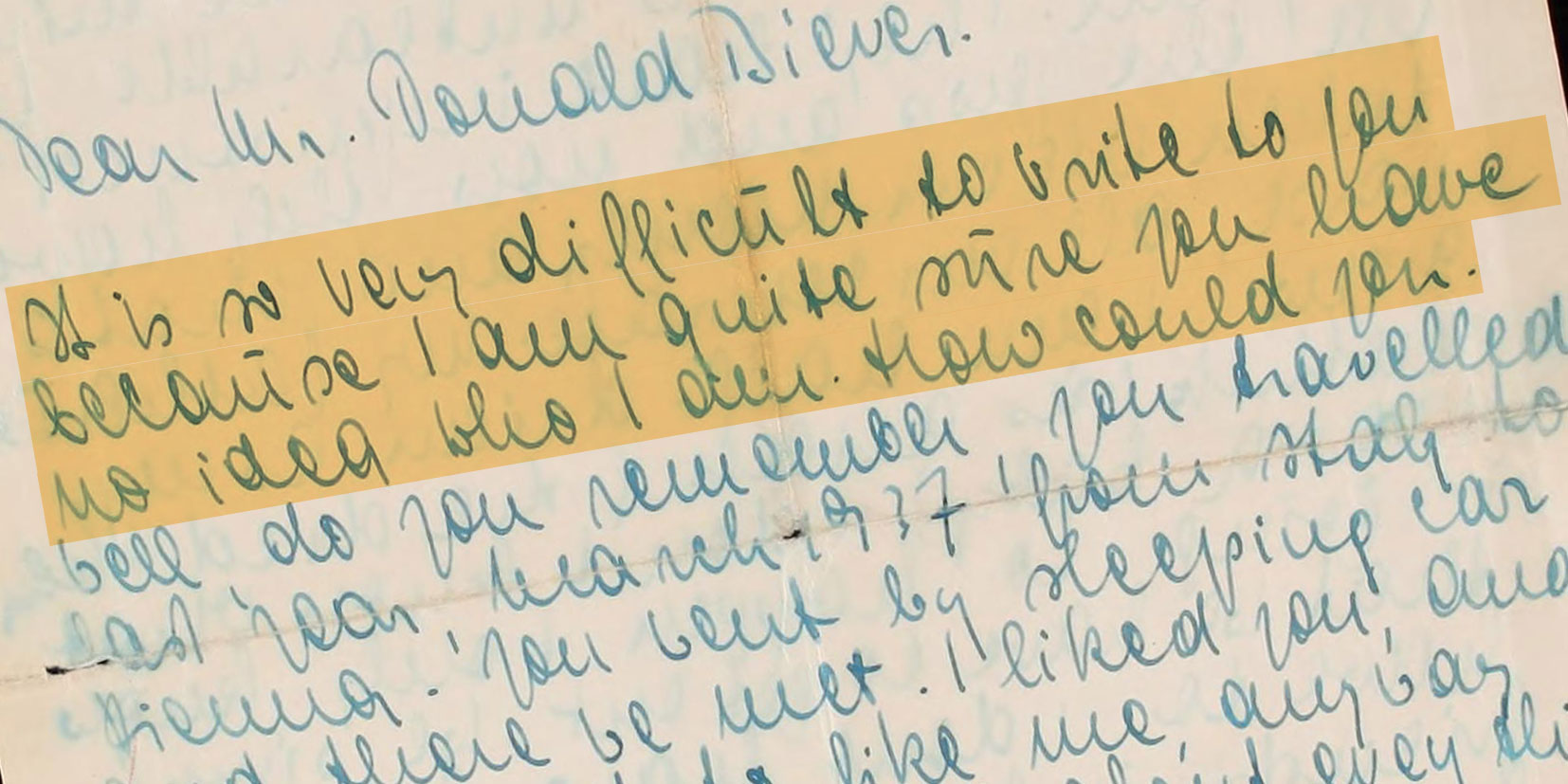

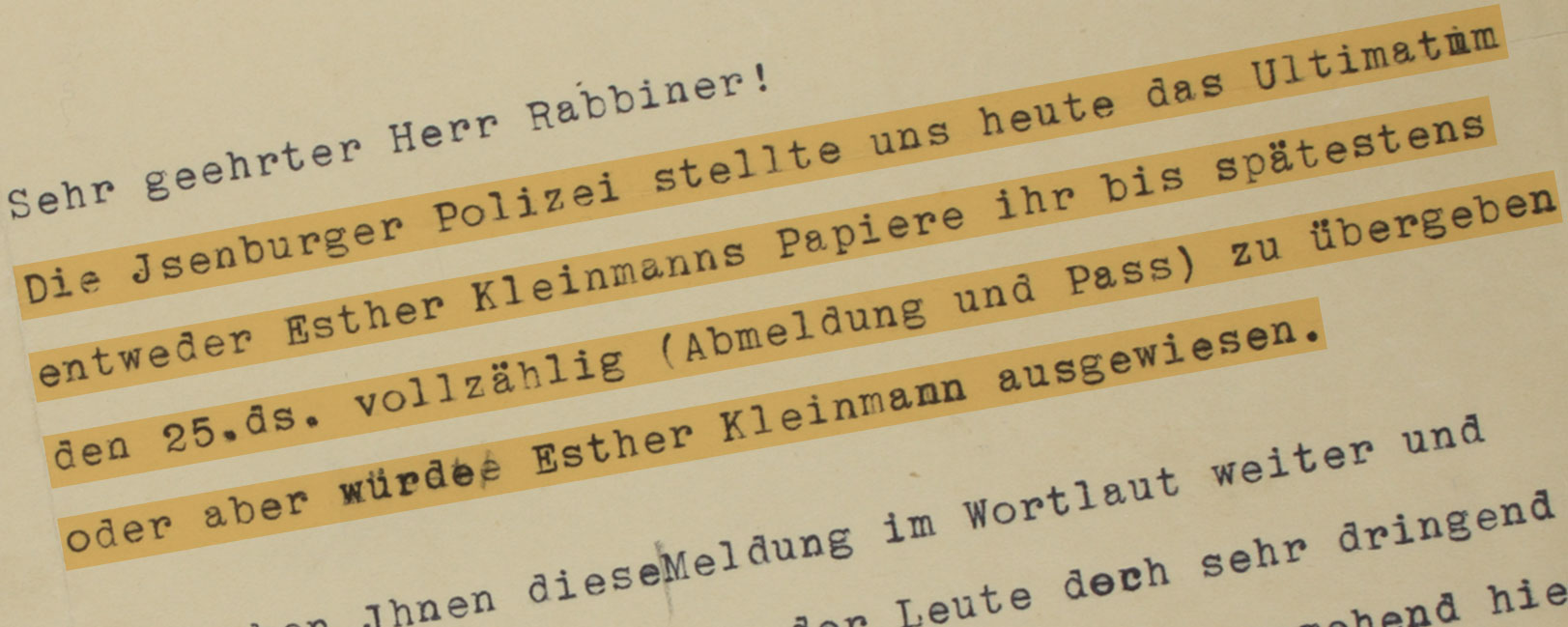

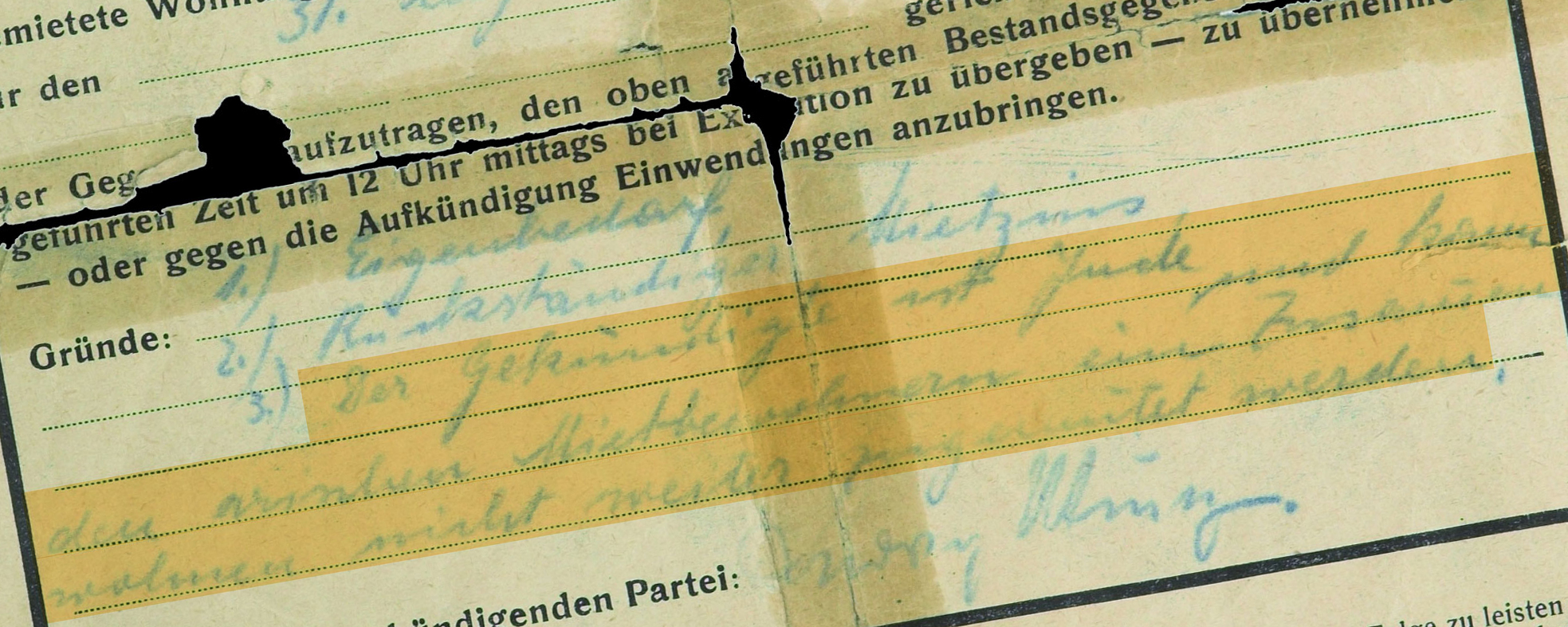

“The tenant, whose lease was terminated, is a Jew, and fellow tenants can no longer be expected to live side-by-side with him.”

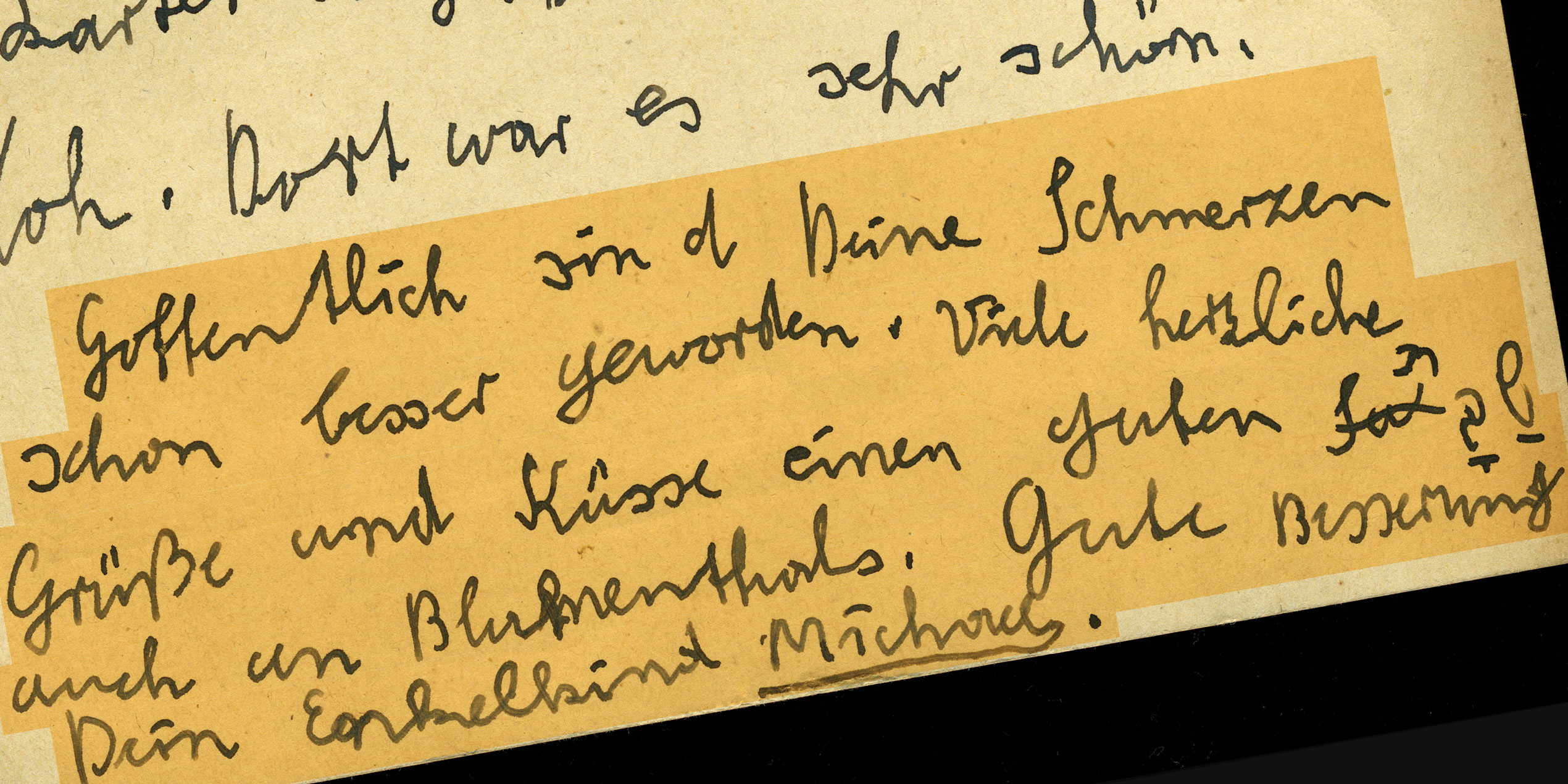

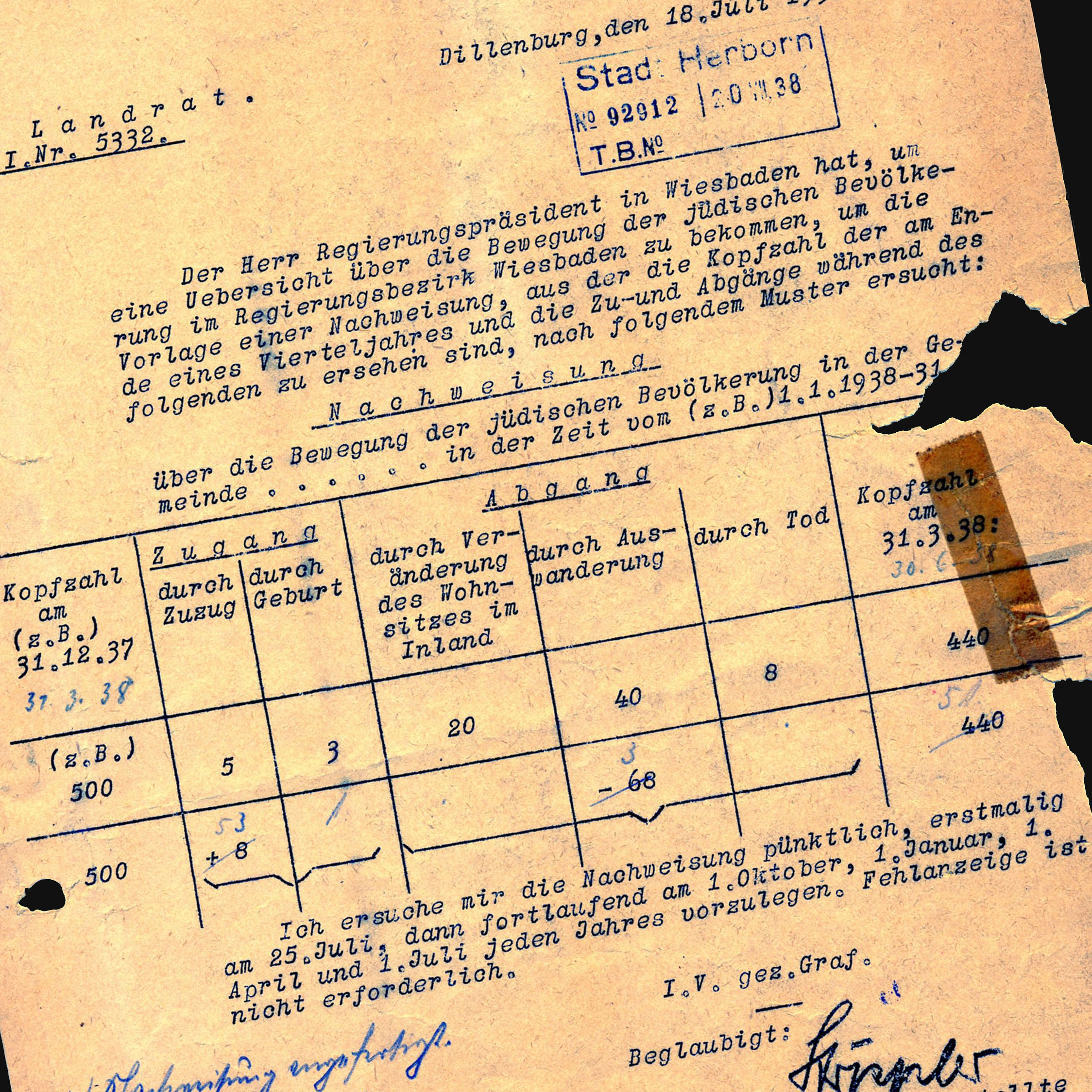

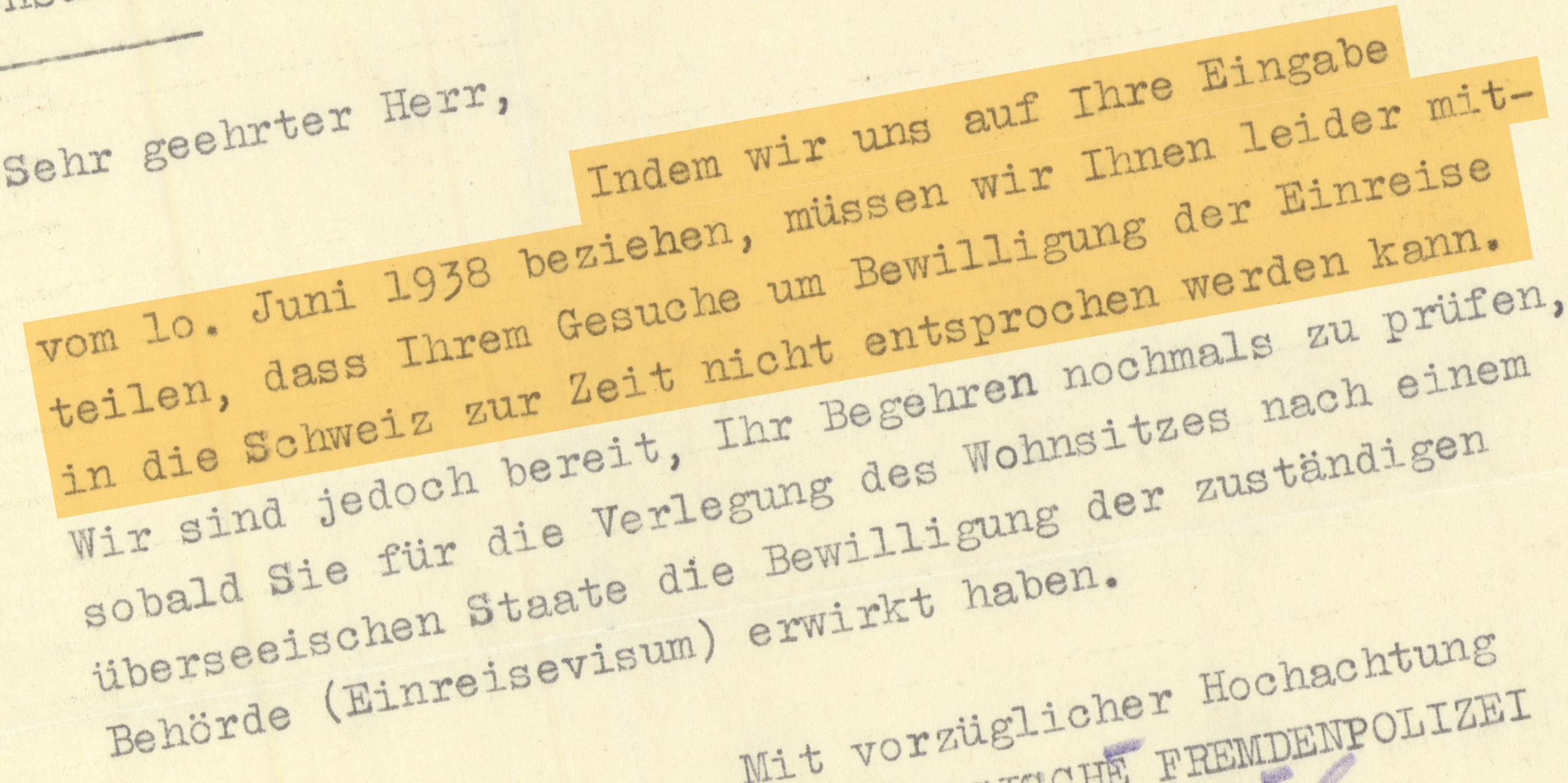

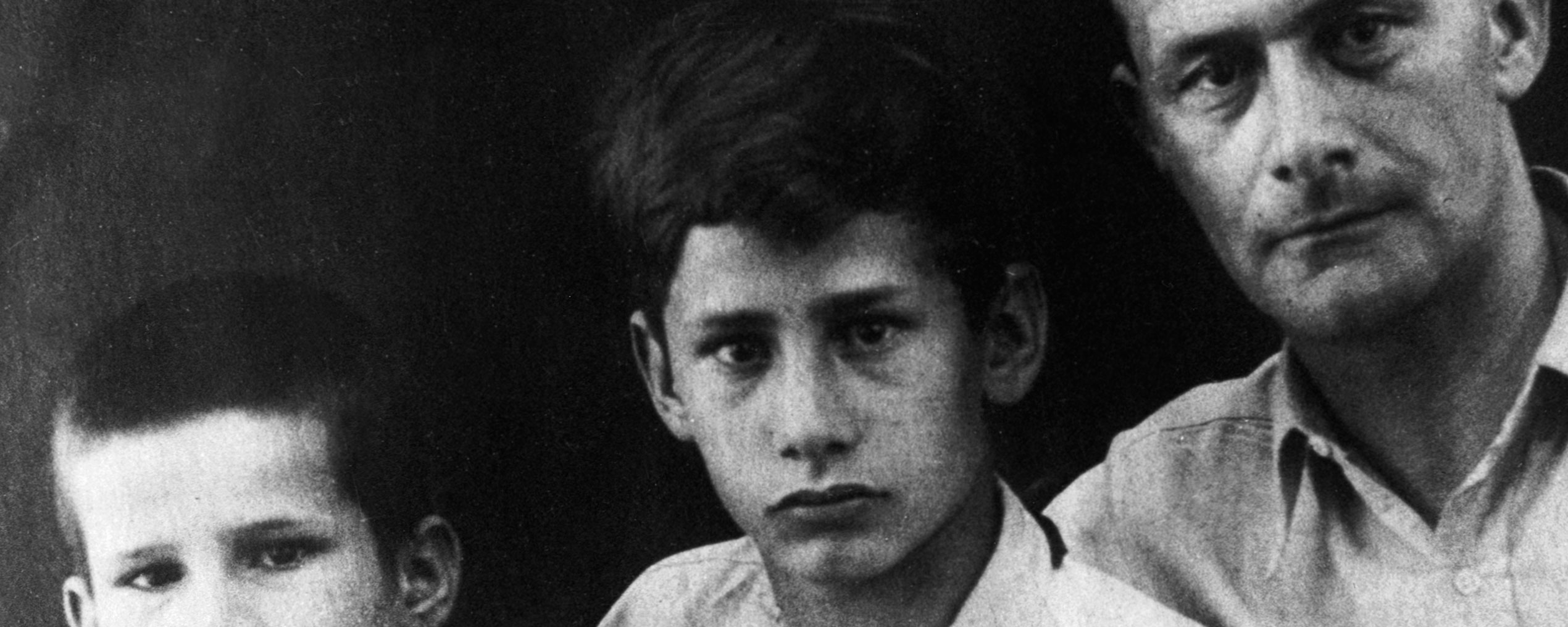

VIENNA

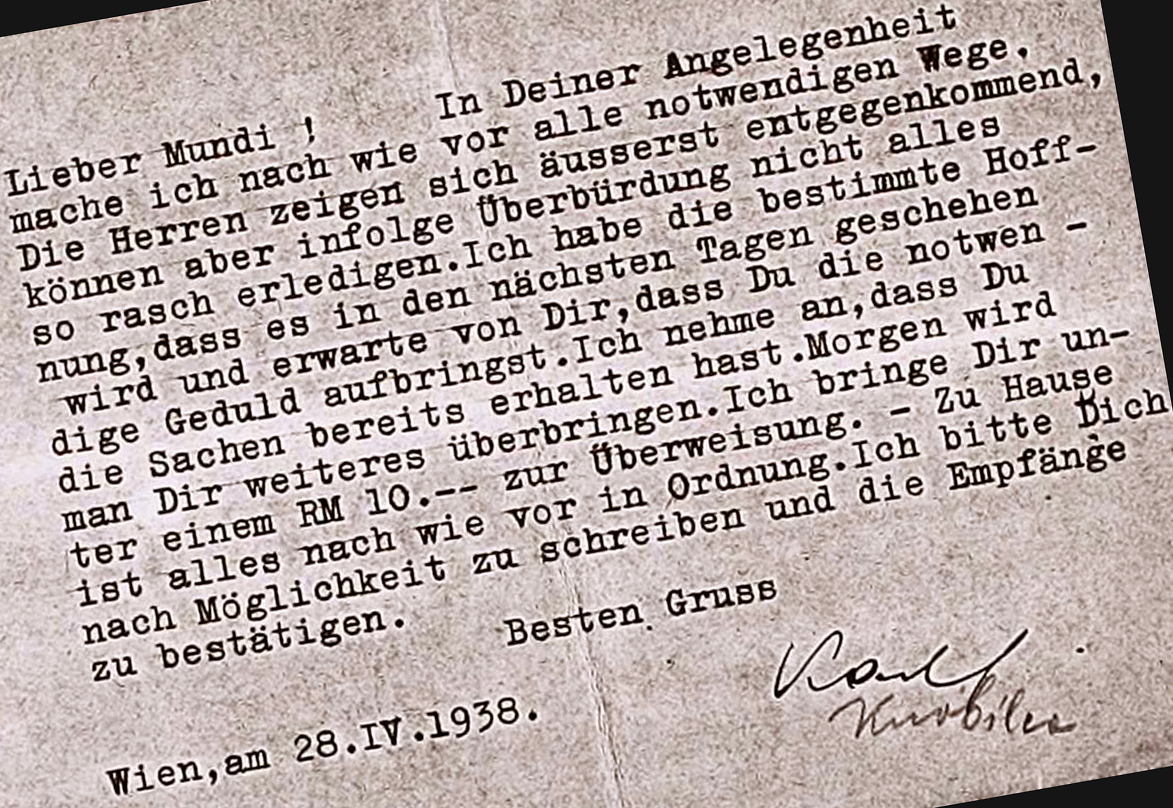

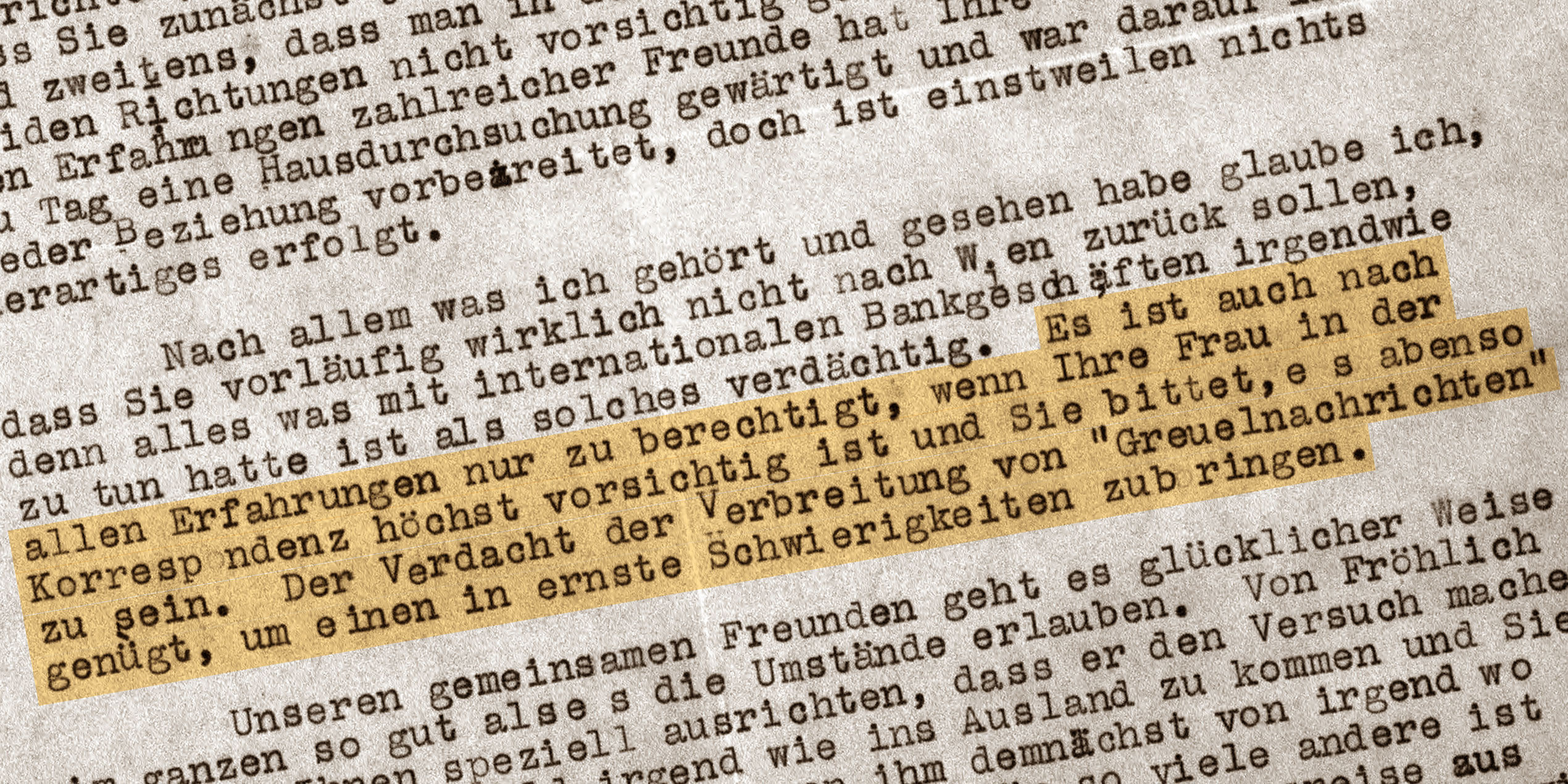

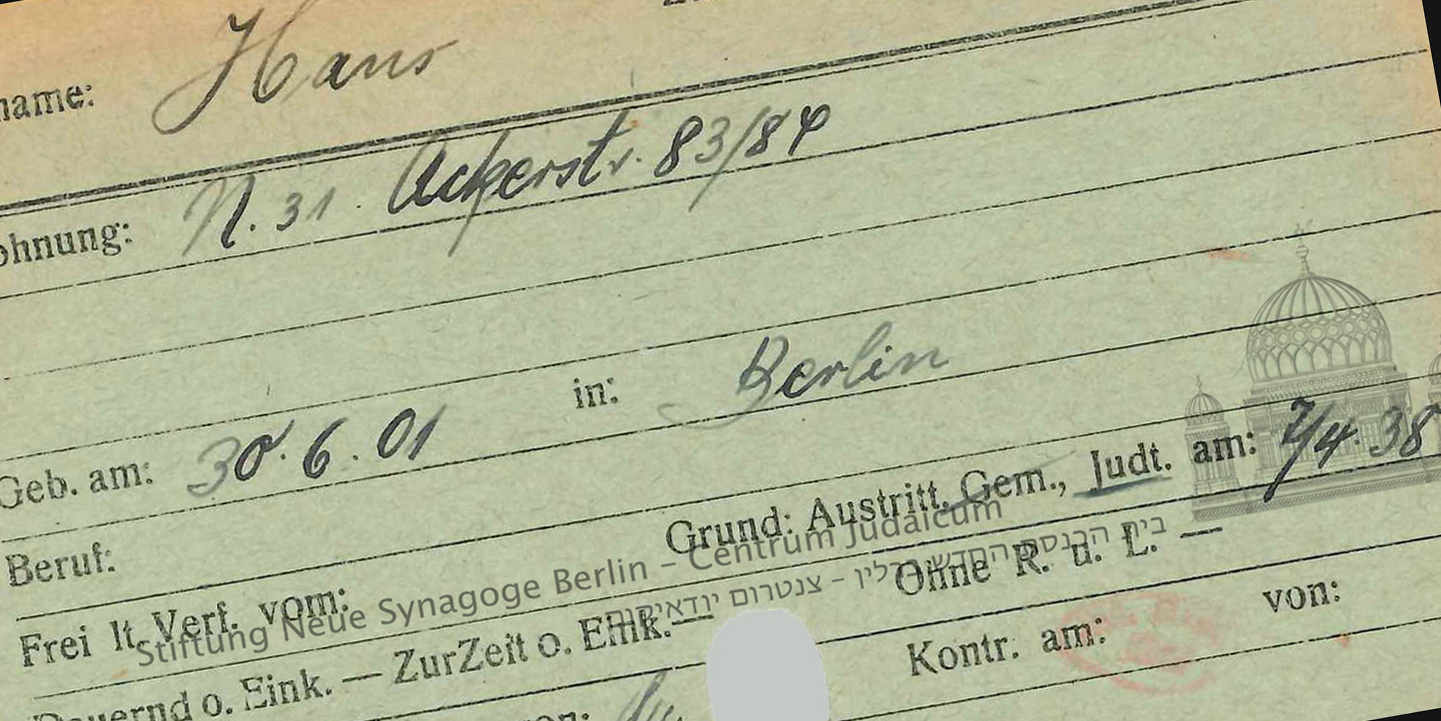

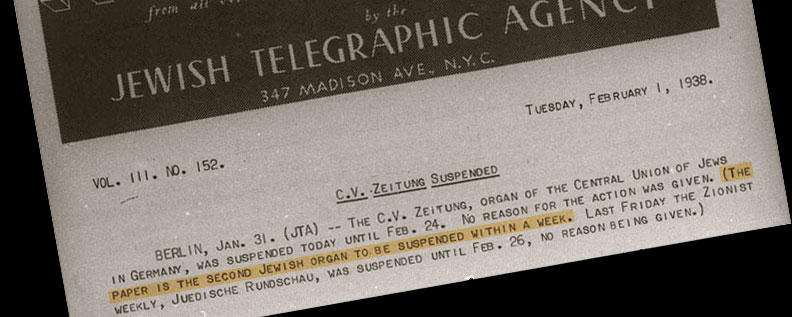

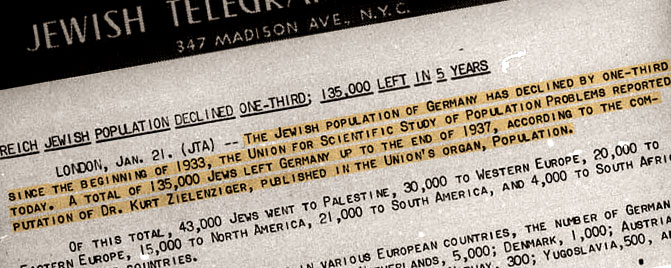

Until 1938, about 60,000 Jews lived in the Leopoldstadt district of Vienna, a fact that earned it the moniker “Isle of Matzos.” Between the end of World War I and the rise of “Austrofascism” in 1934, the Social-Democratic municipal government began to create public housing. By the time of the Anschluss in March 1938, there was a massive housing shortage in the city. The Nazis began to evict Jewish tenants from public housing. In light of the tendency of the police to ignore encroachment on Jewish property, it was easy for antisemitic private landlords to follow this example. Being a Jew was enough of a reason for eviction. When house owner Ludwig Munz filled in the eviction order form for his tenants Georg and Hermine Topra, he came up with as many as three reasons: his own purported need for the place, back rent, and consideration for the neighbors, who could not be expected to put up with having to live side-by-side with Jews.