Between a rock and a hard place

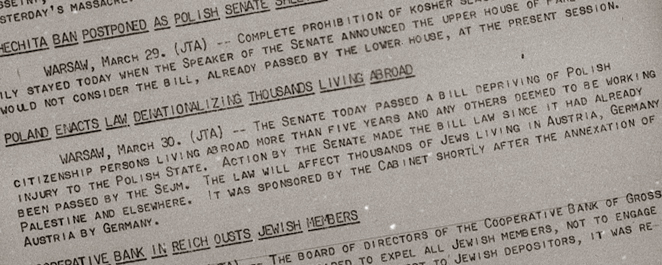

Fears mount near the border between Czechoslovakia and Poland

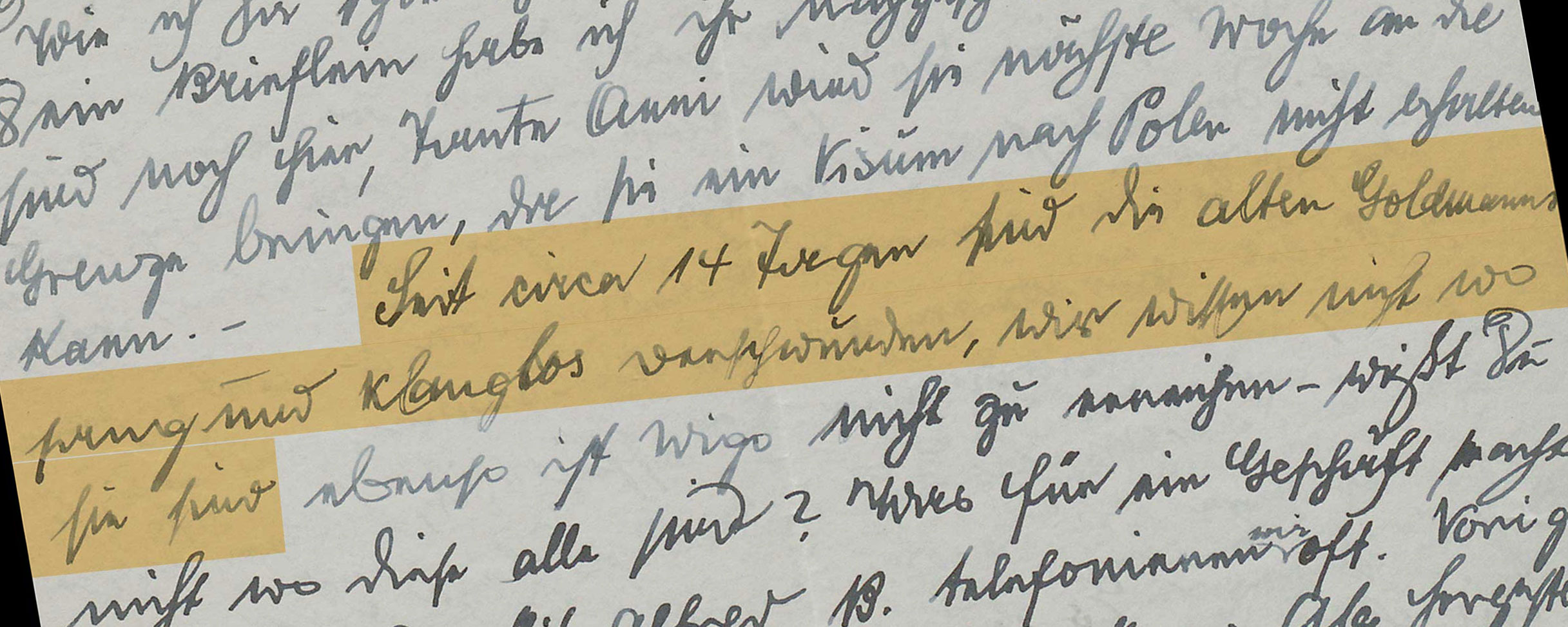

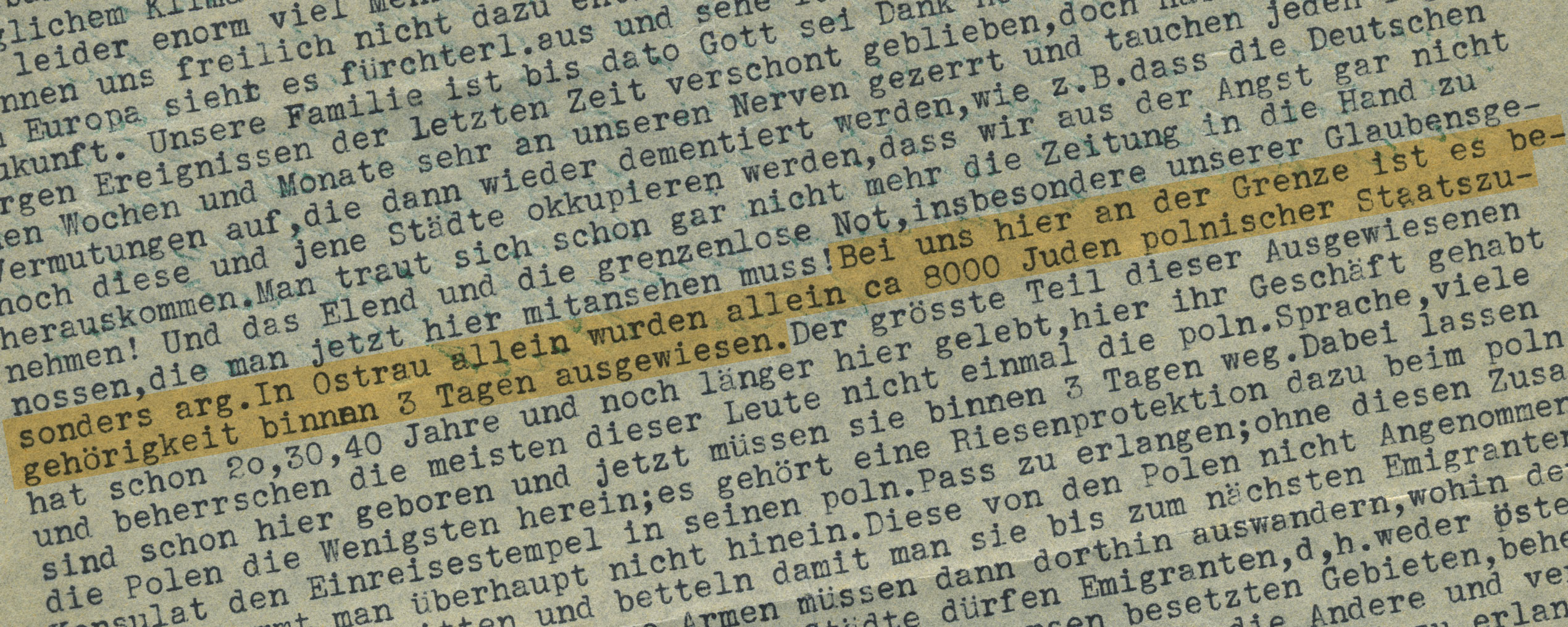

“Here with us near the border it is especially bad. In Ostrau alone, 8,000 Jews of Polish nationality were expelled within 3 days.”

Mährisch Ostrau, Moravia

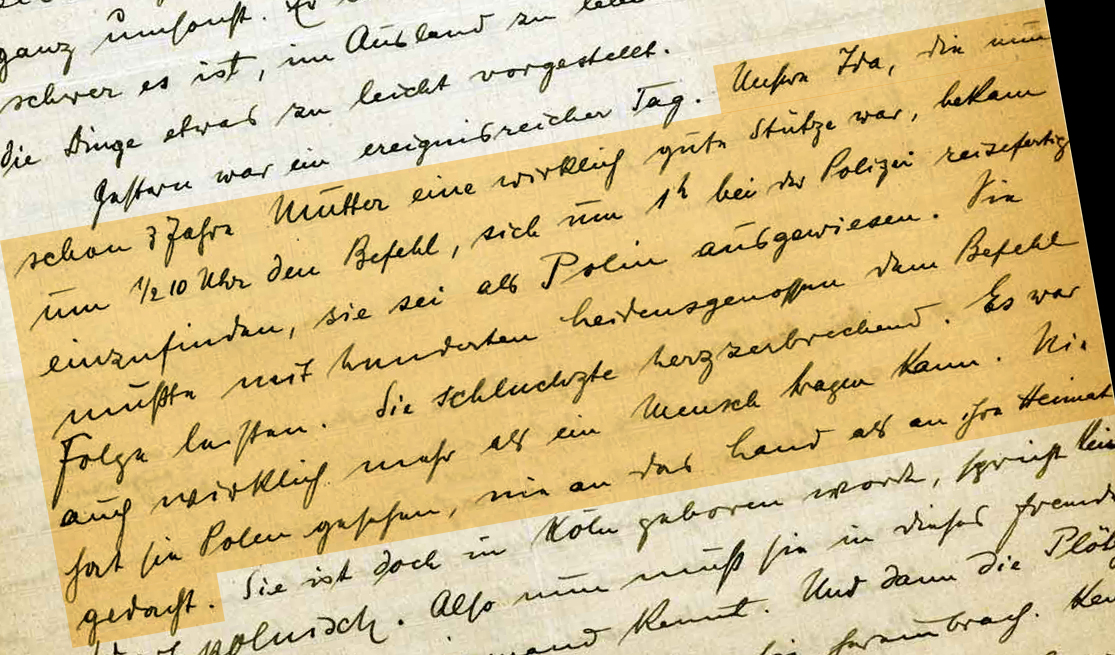

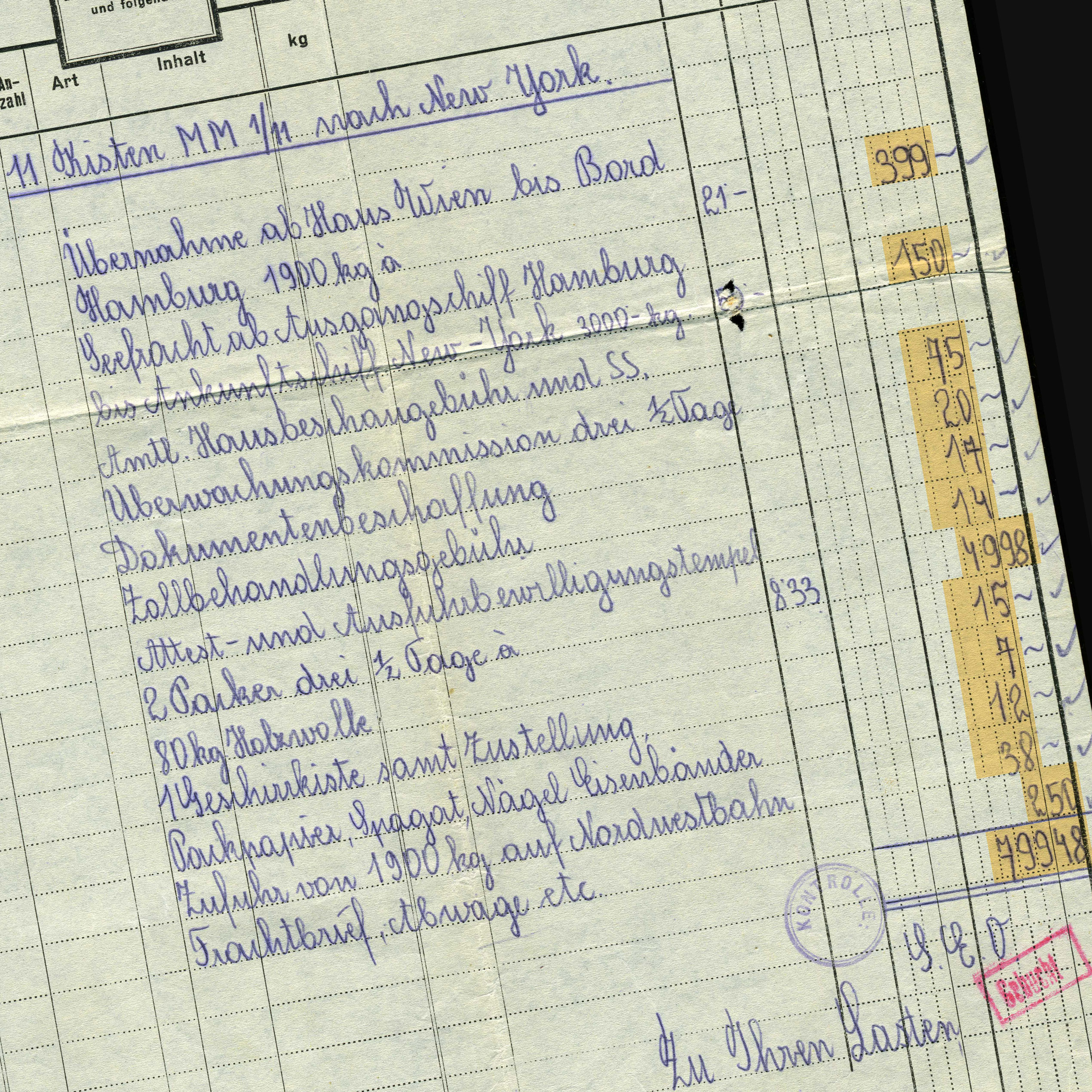

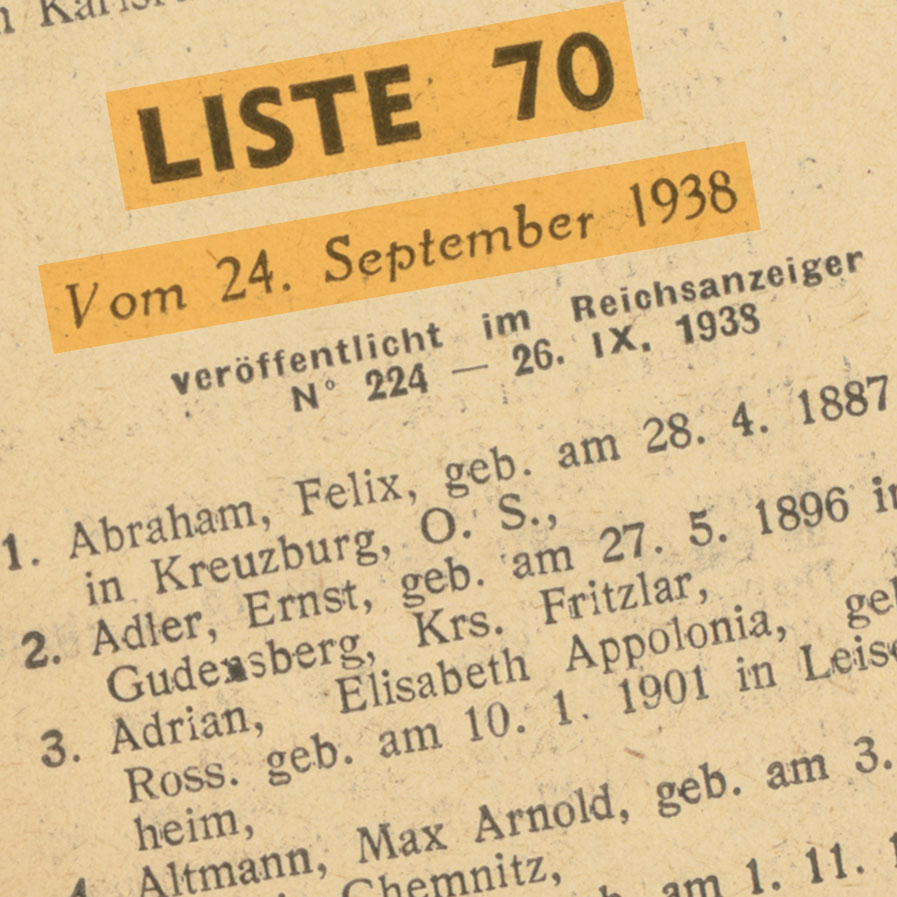

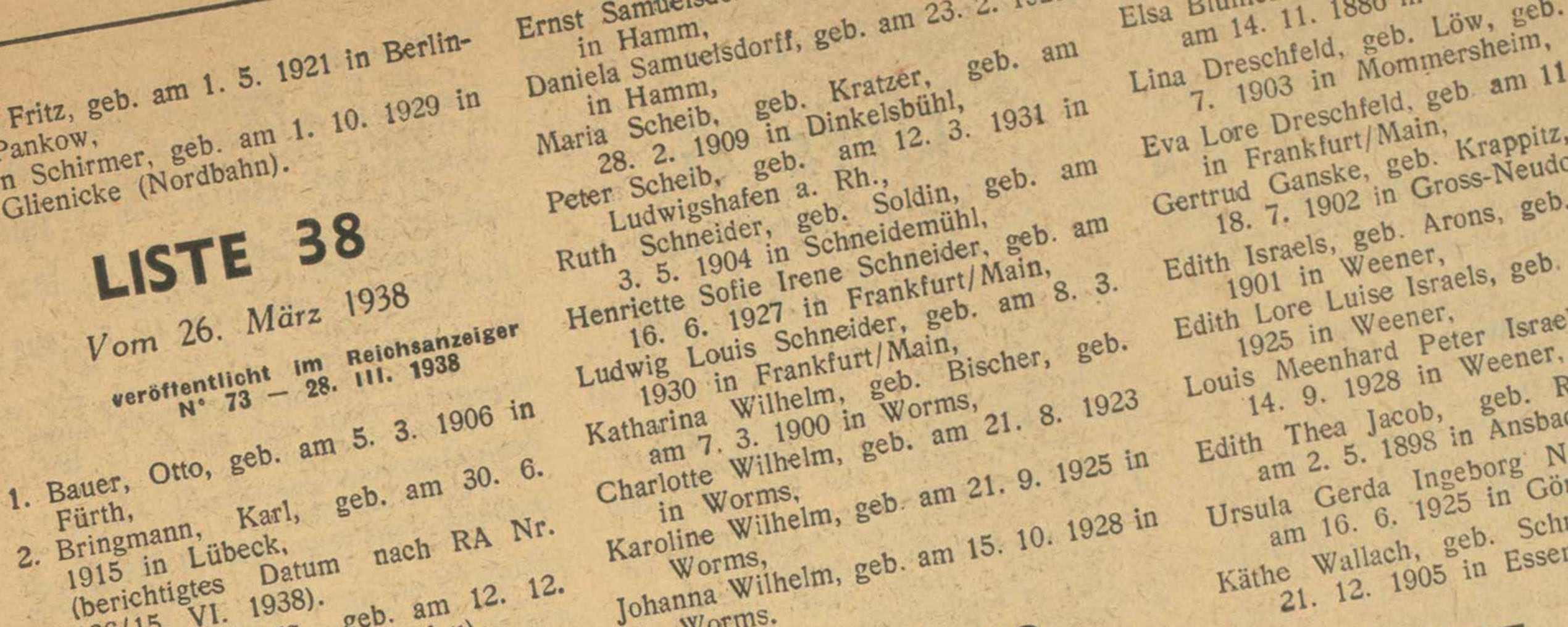

Lilly and Sim, a married couple in Mährisch Ostrau (Moravia), had so far been spared major hardship – at least on a personal level. But fear was mounting in the city near the Czech-Polish border because new rumors came up on a daily basis about which cities the Germans would occupy next. The worst news was about the fate of fellow Jews: in this December 10th, 1938, letter, Lilly tells her friends abroad about no fewer than 8,000 Jews of Polish extraction, who within three days had been forced to leave the city, some of them after having lived there for 20, 30 or even 40 years. Her greatest wish – getting out – was hard to realize, and she simply could not face joining a refugee transport to a random country “with an impossible climate” to work as farm hands. Meanwhile, Sim was facing a promotion, but given the total uncertainty of the future – with an agreement between Czechoslovakia and Poland pending, the couple did not even know which nationality they were at this point – the prospect did not occasion much joy.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Willy Nordwind Collection, AR 10551

Original: