Embracing tomorrow

A refugee gives advice to refugees

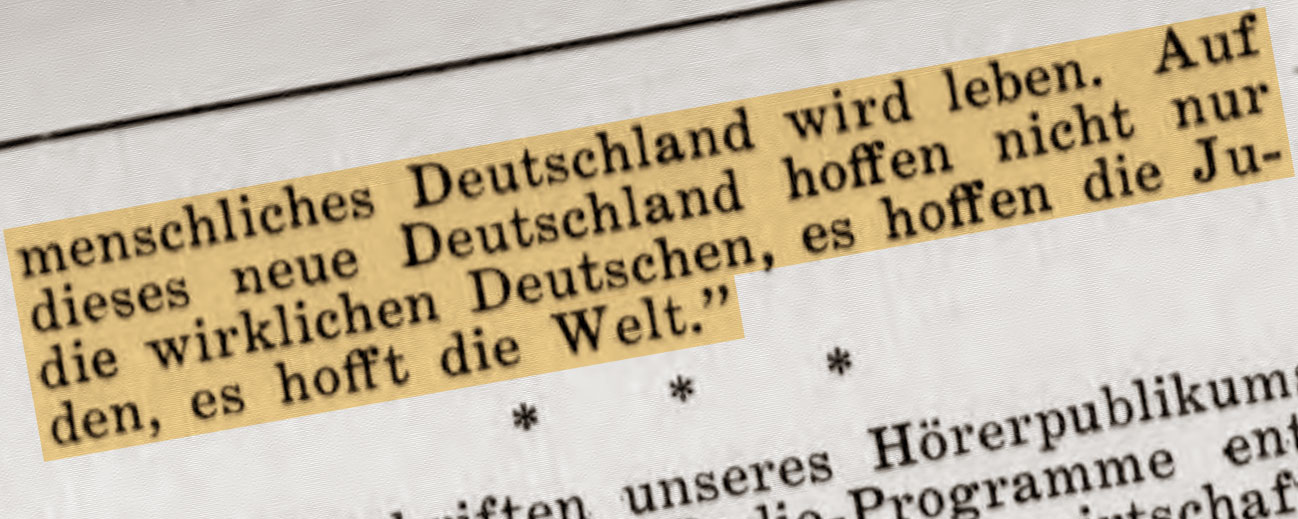

“We remain fighters for a free, just, clean Germany. This underworld must come to an end, it will come to an end! A humane Germany will live. Not only are the real Germans hoping for this real Germany, but the Jews are hoping, the world is hoping.”

New York

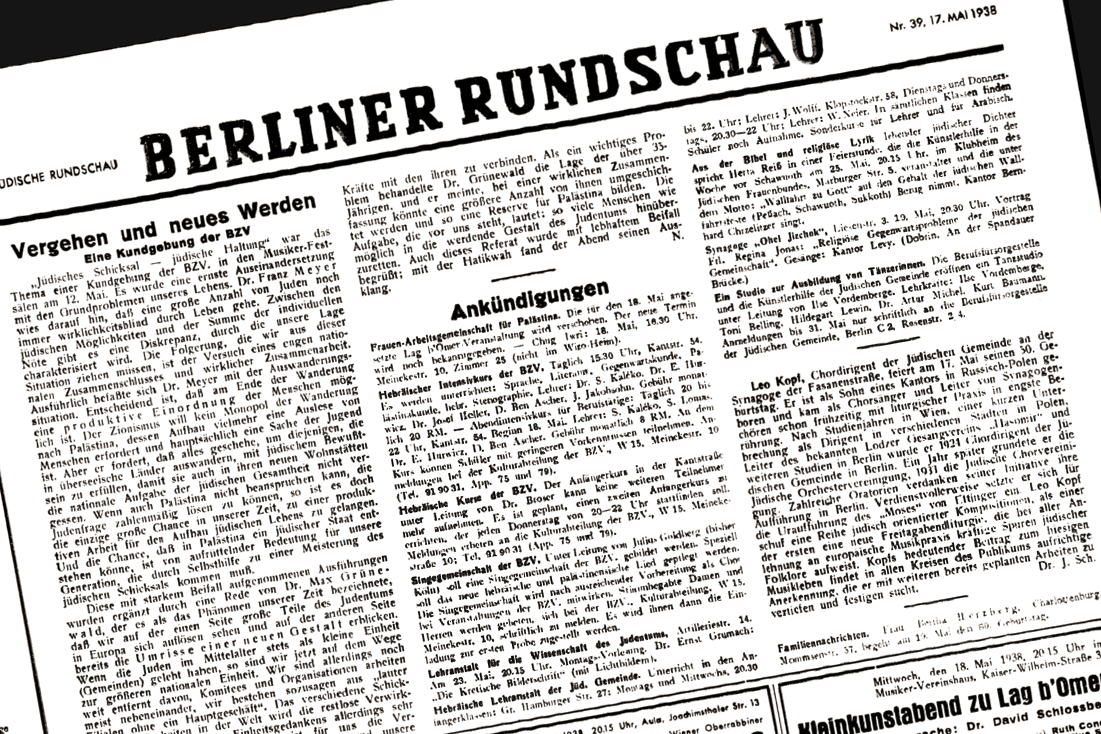

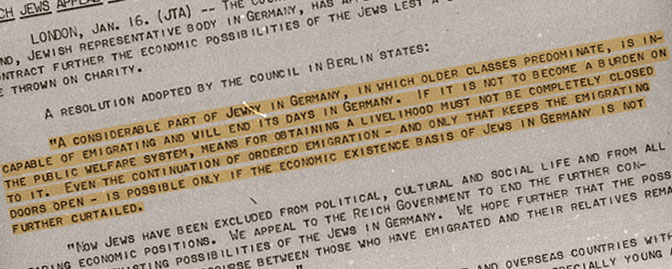

For four years, Aufbau, the newsletter of the German-Jewish Club in New York, had served immigrants as a cultural and emotional anchor and as a source of useful information. The December issue brings a gushing report on the Club’s newly established weekly radio program. Among the prominent speakers who were asked to contribute speeches to inaugurate the program was Dr. Joachim Prinz, a former Berlin rabbi and outspoken opponent of the Nazis. Forging a bridge from the days of the exodus from Egypt via a history of emigrations to the present predicament, he made no attempt to minimize the emigrants’ plight. At the same time, likening the situation of his community to that of Jewish refugees from the Spanish Inquisition, he saw the potential in the challenges of emigrant life in America. The new program, he felt, was “an important instrument of education as Jews and as people of freedom.” The call of the moment was clear: “We must embrace Tomorrow and bury Yesterday. We must try to be happy again.”