A super woman

Woman entrepreneur turned housewife takes charge

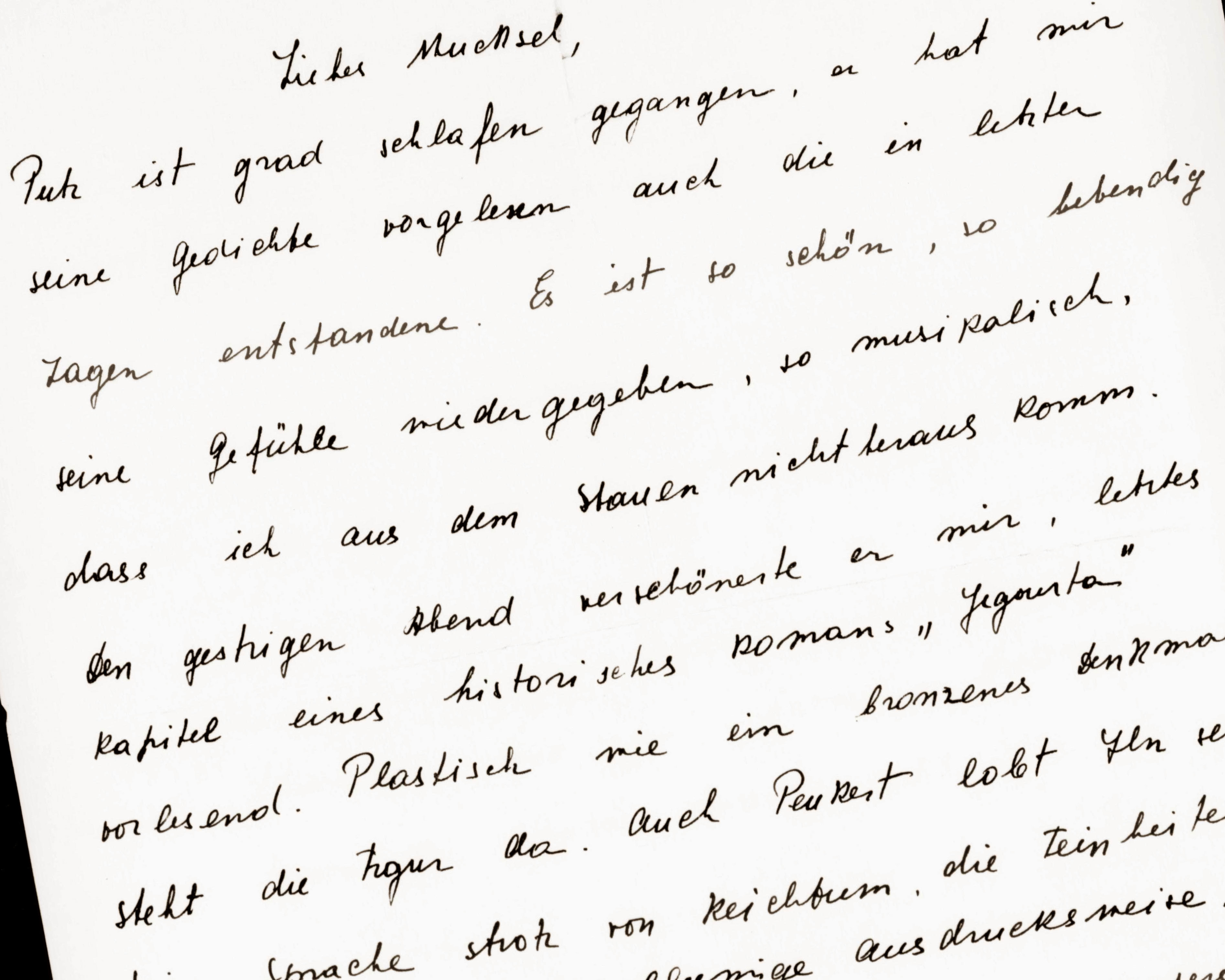

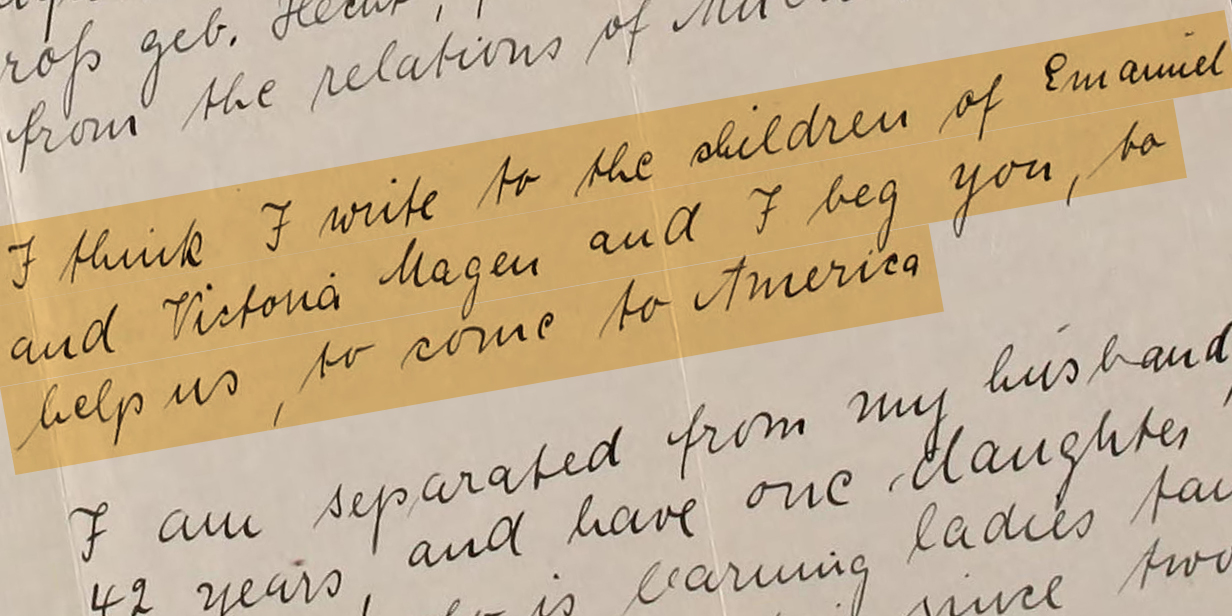

“I think I write to the children of Emanuel and Victoria Magen and I beg you to help us to come to America.”

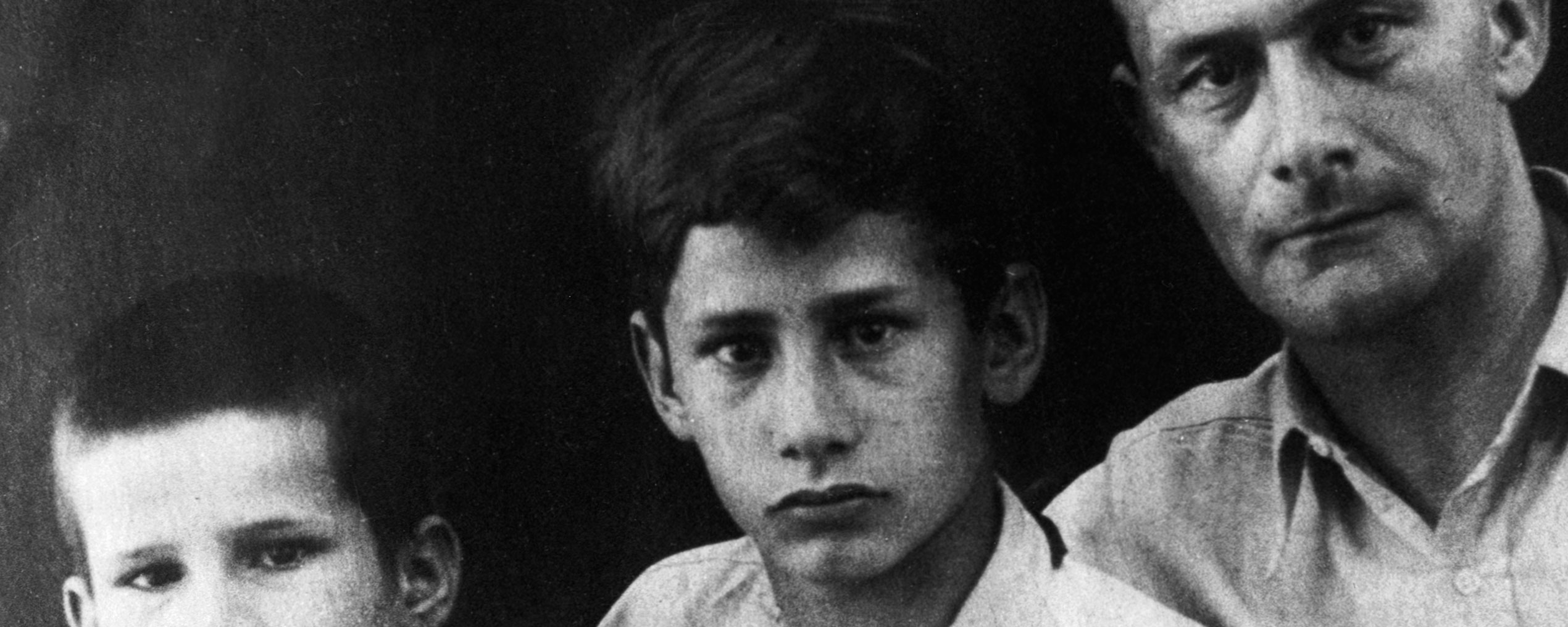

Berlin

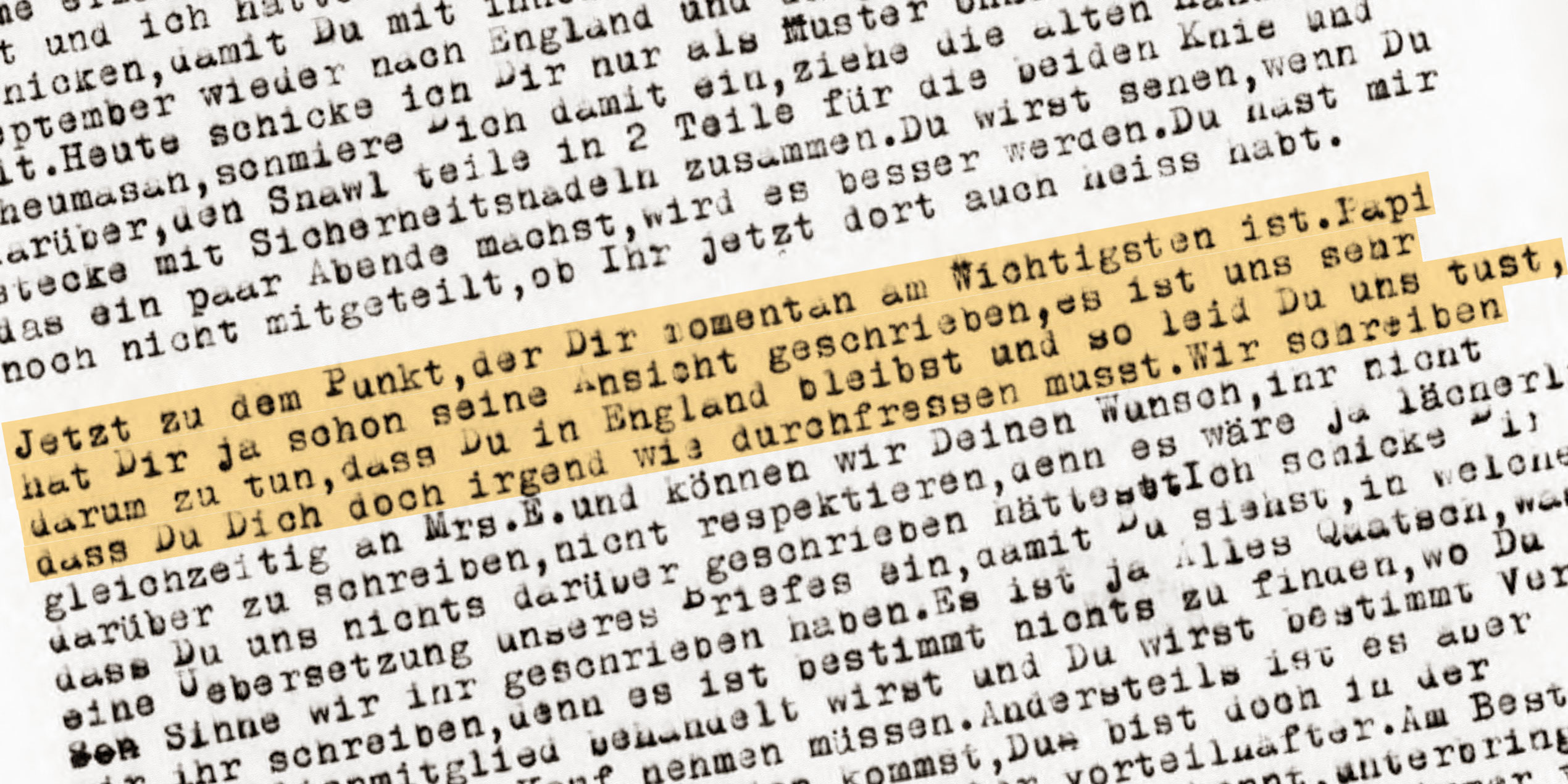

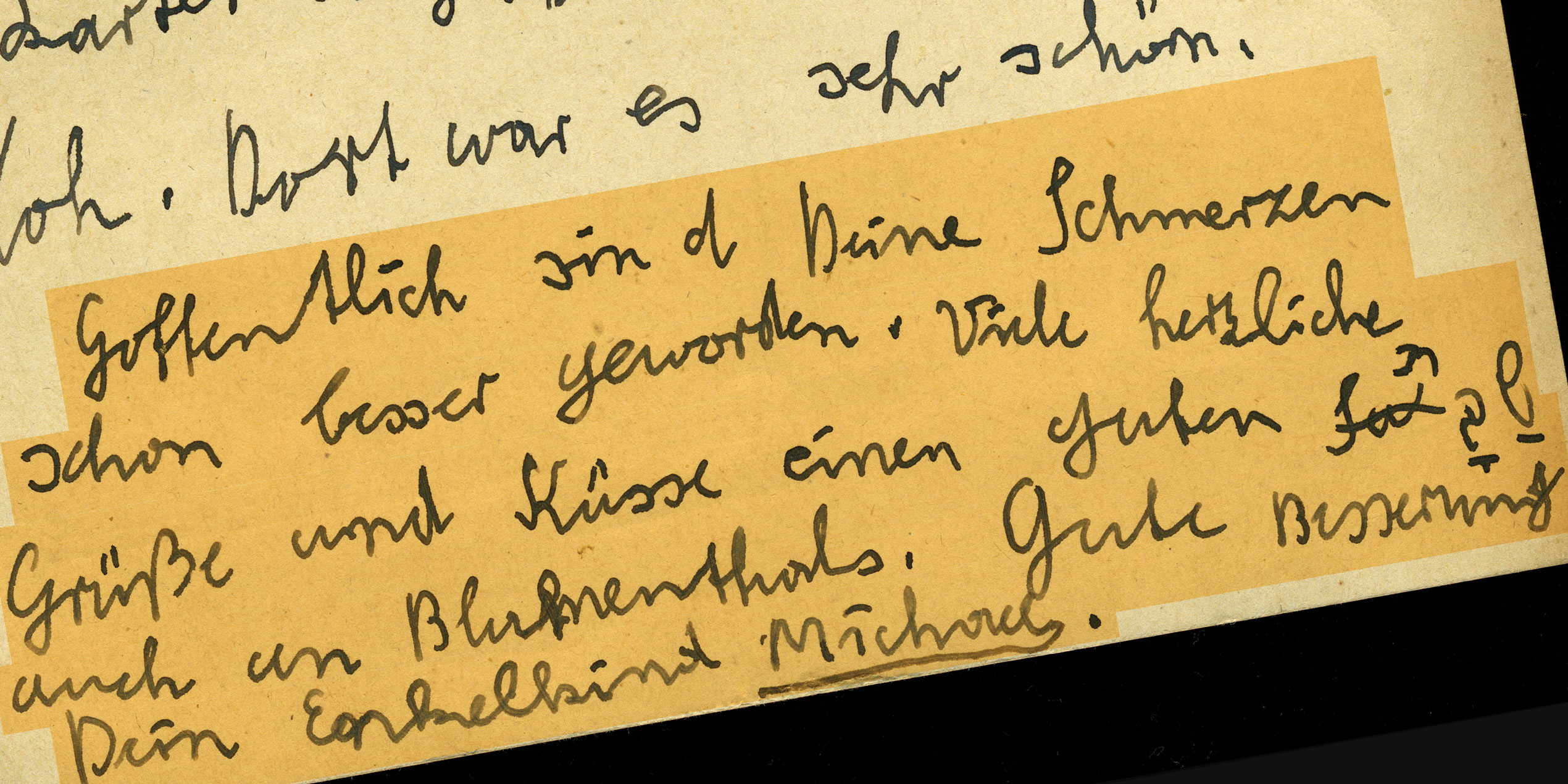

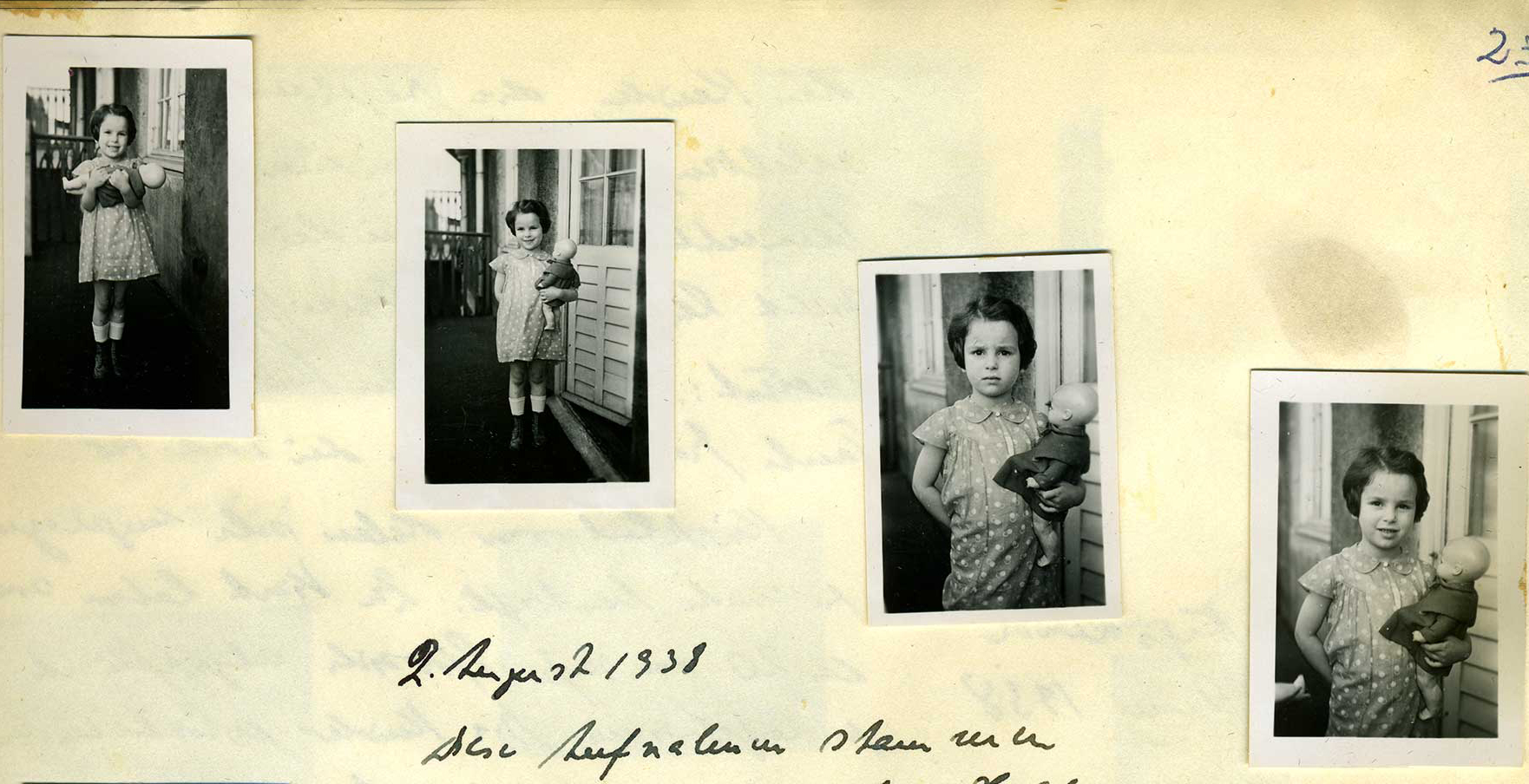

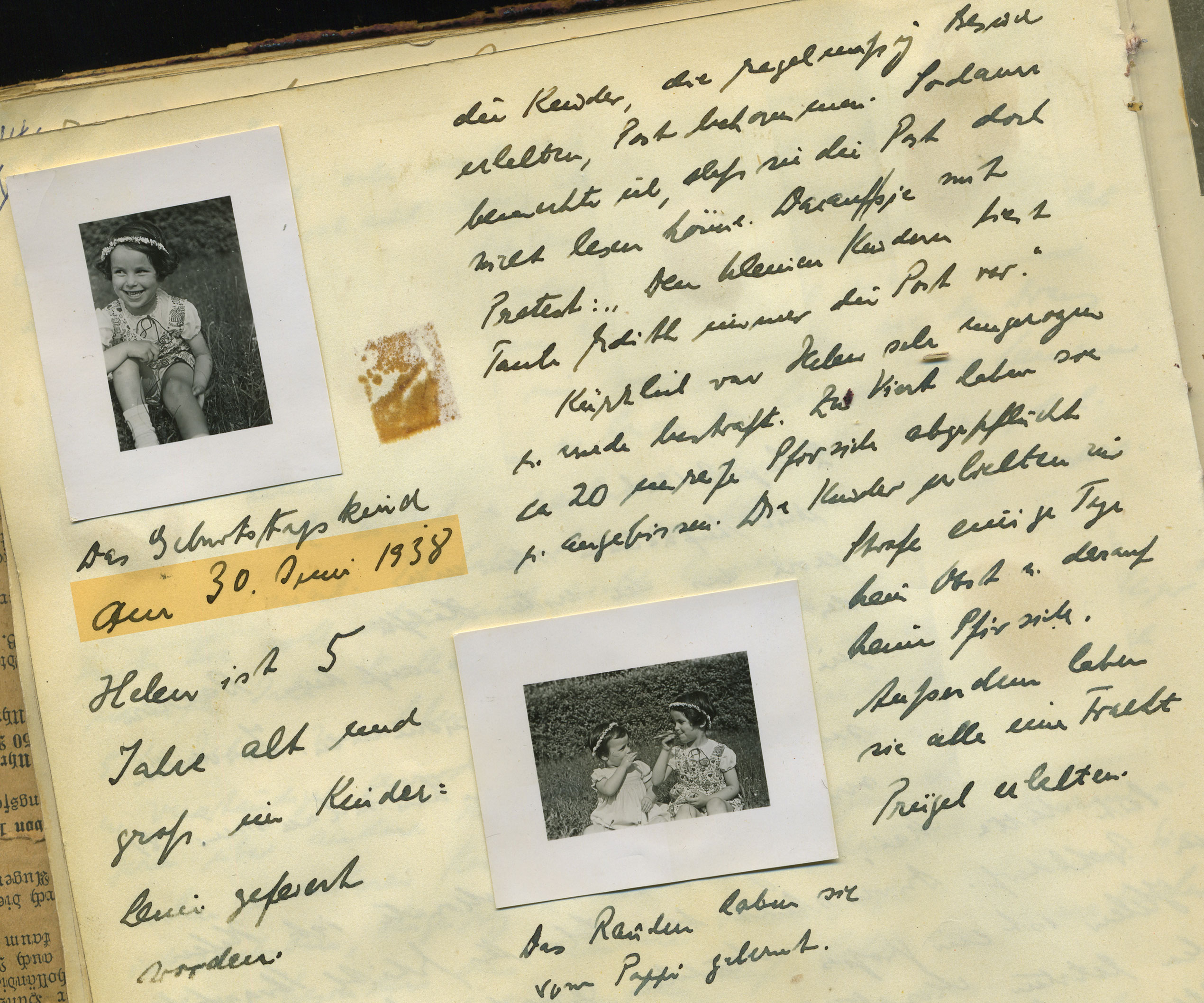

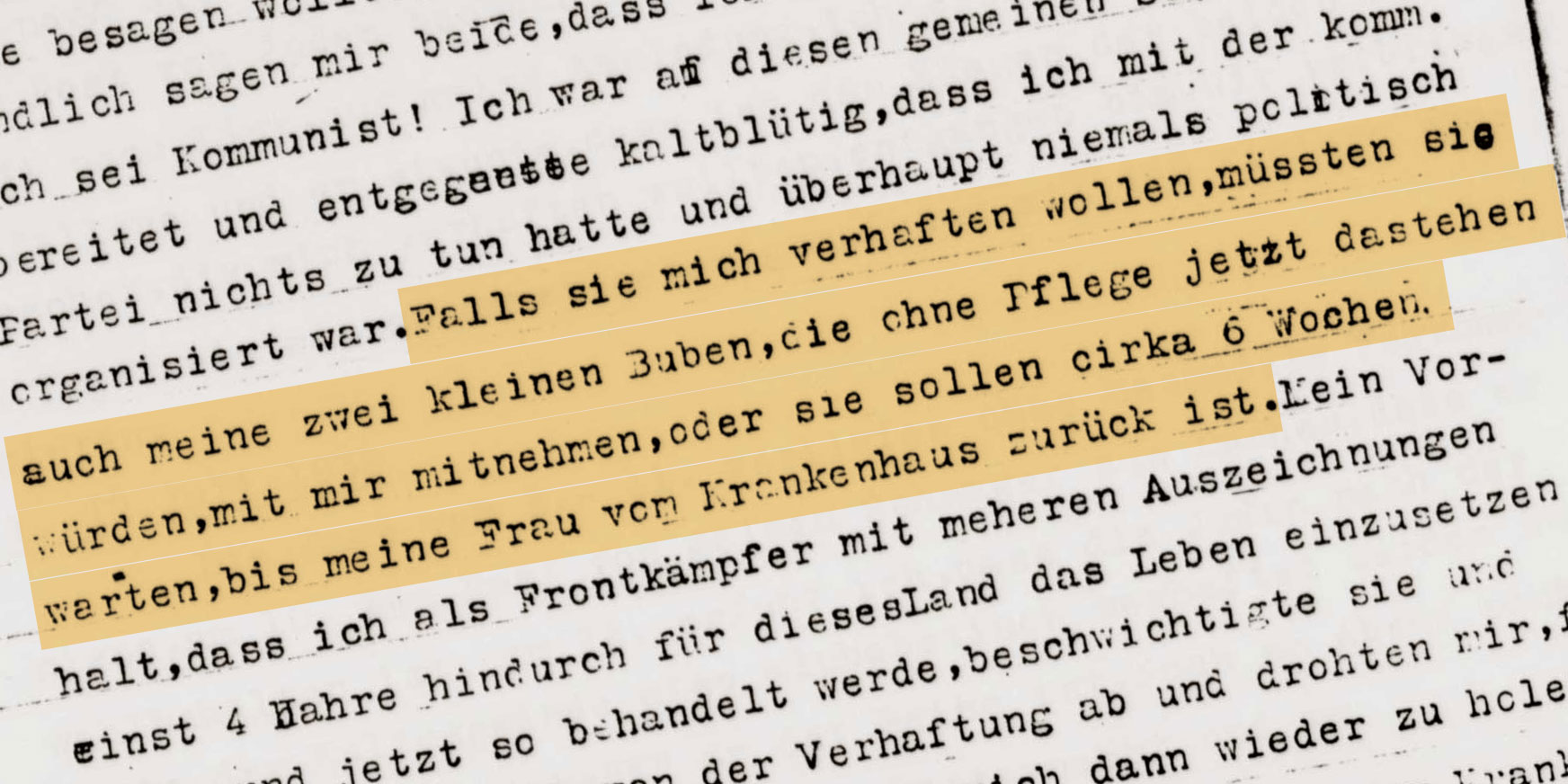

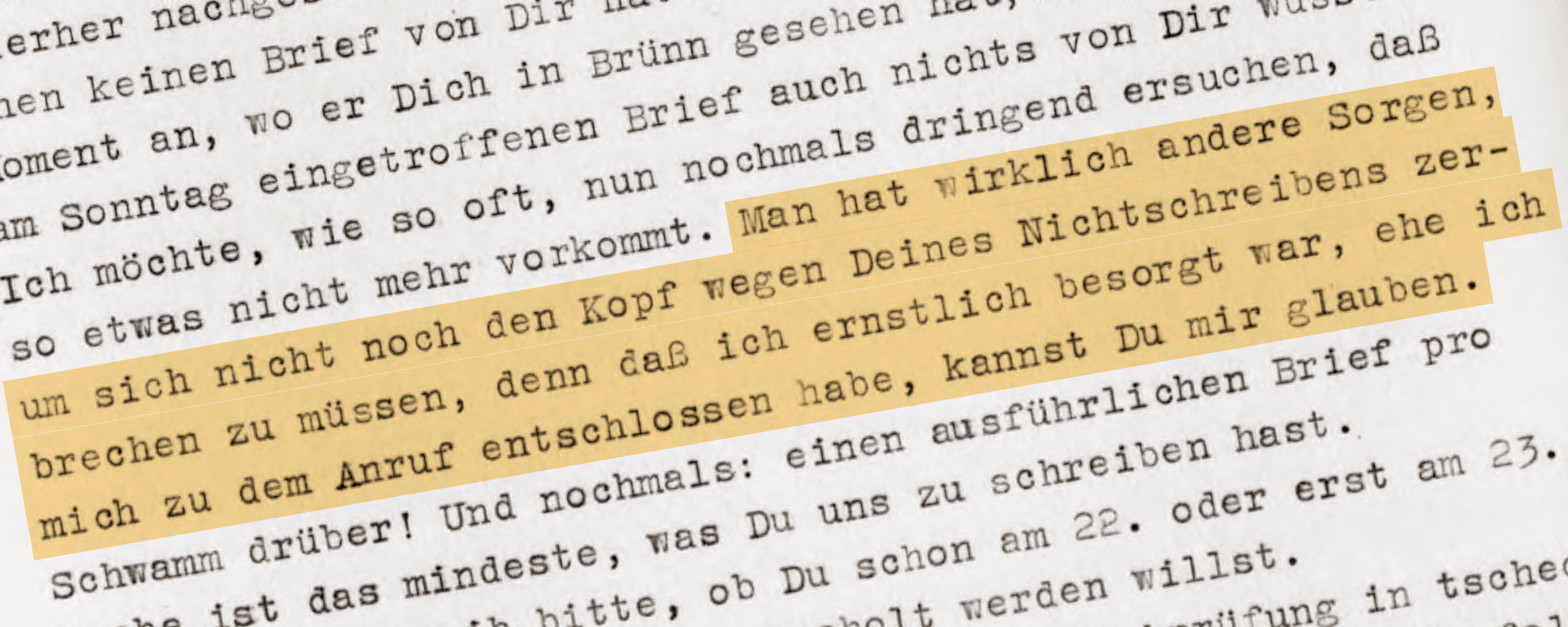

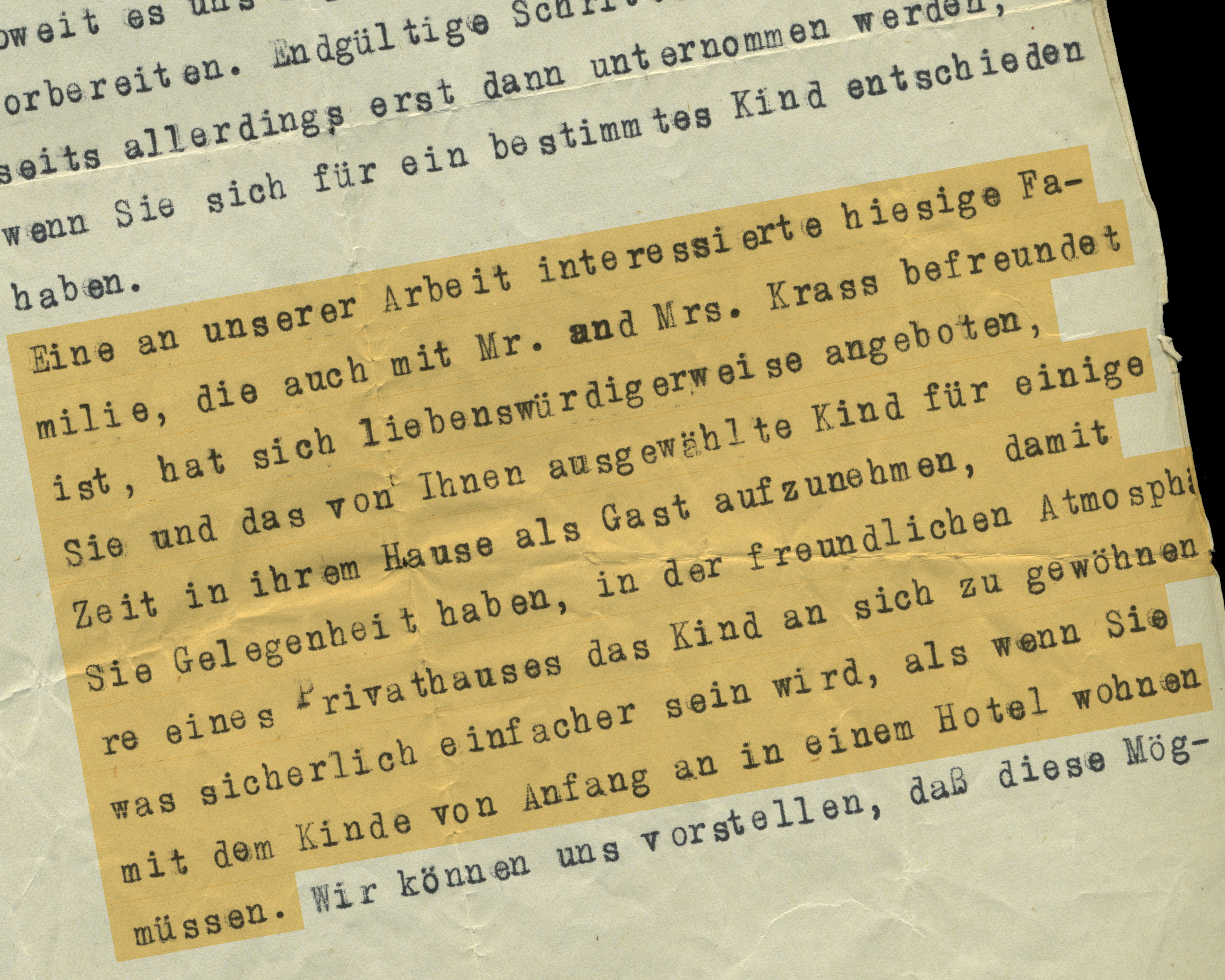

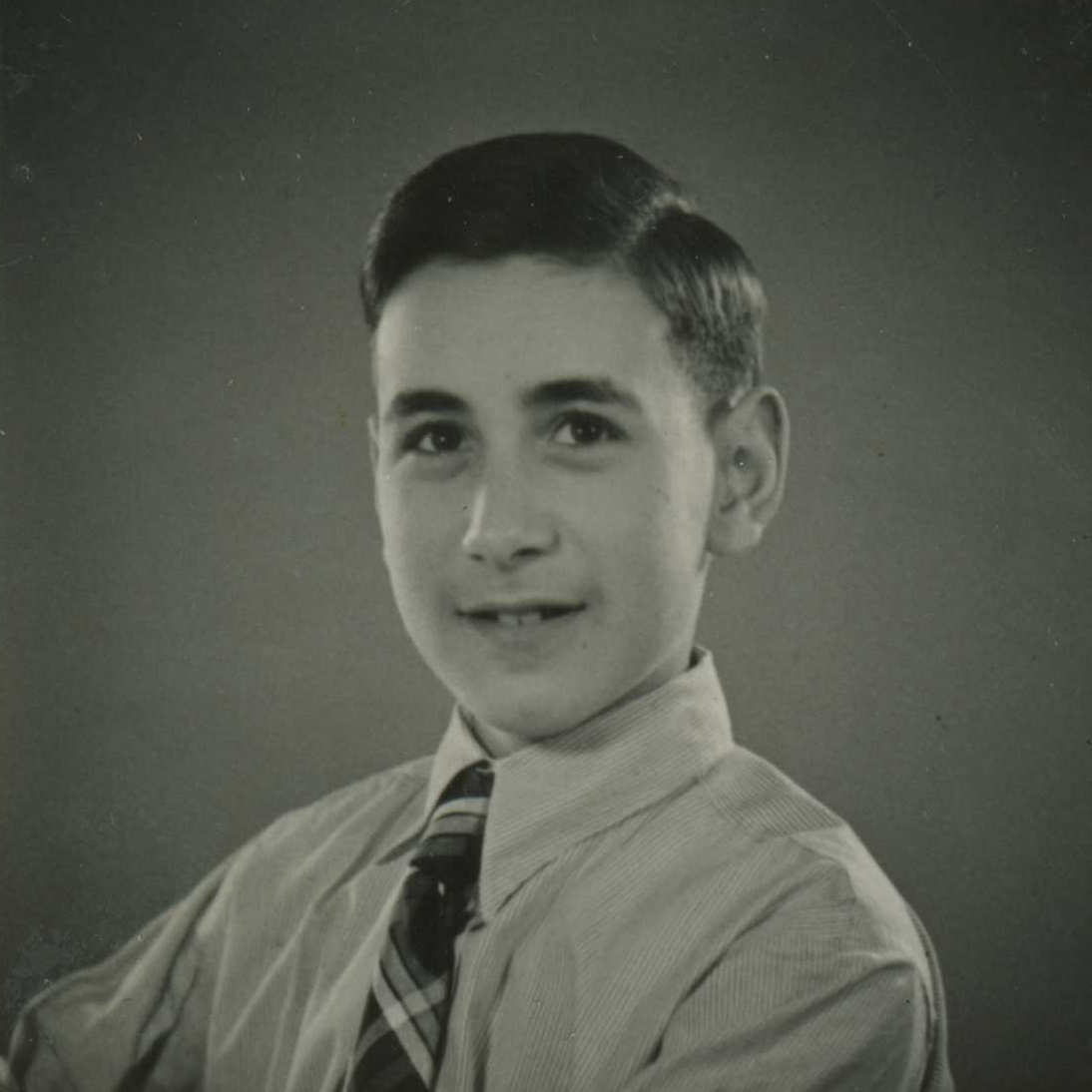

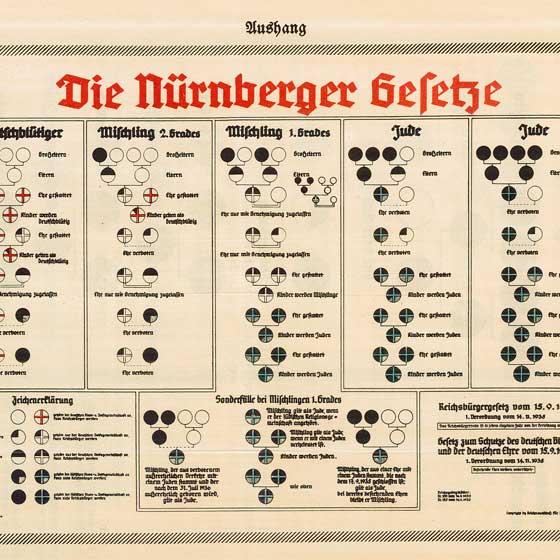

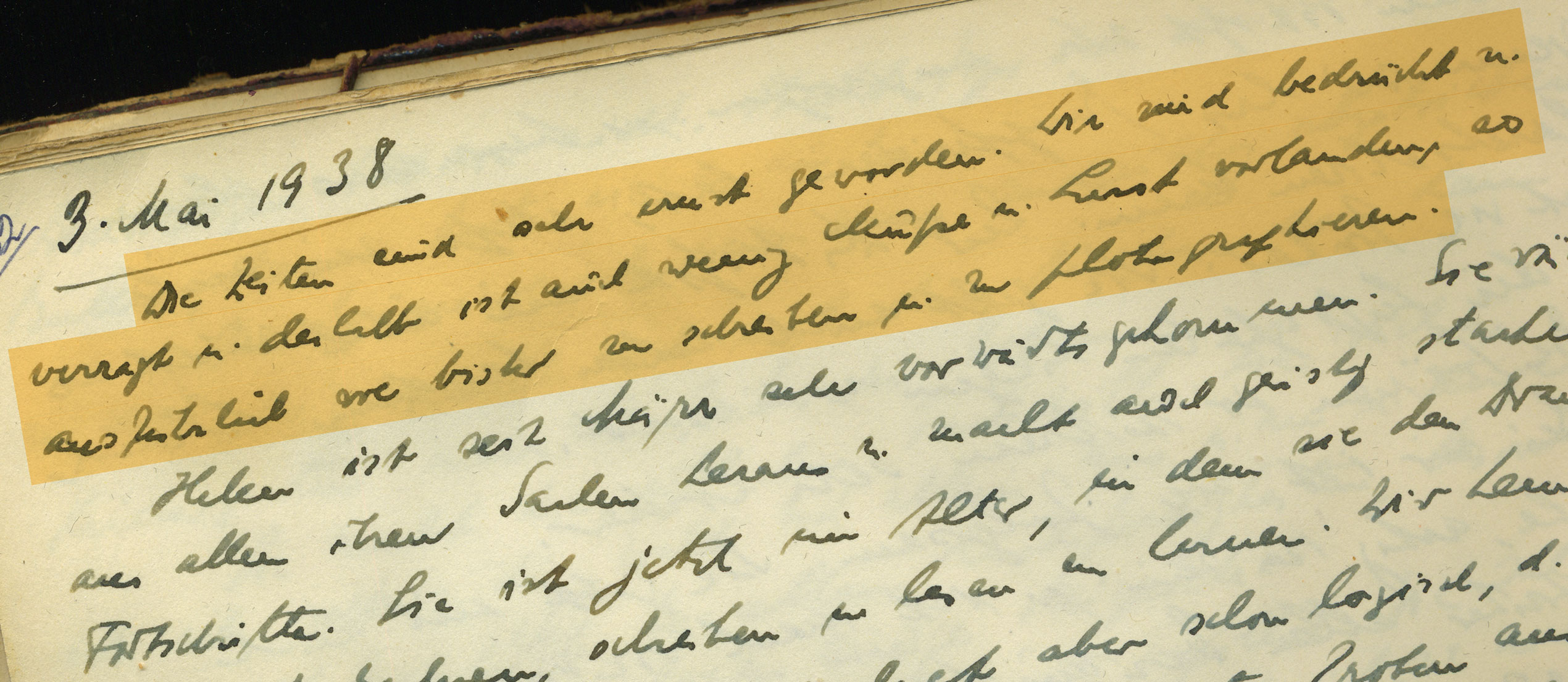

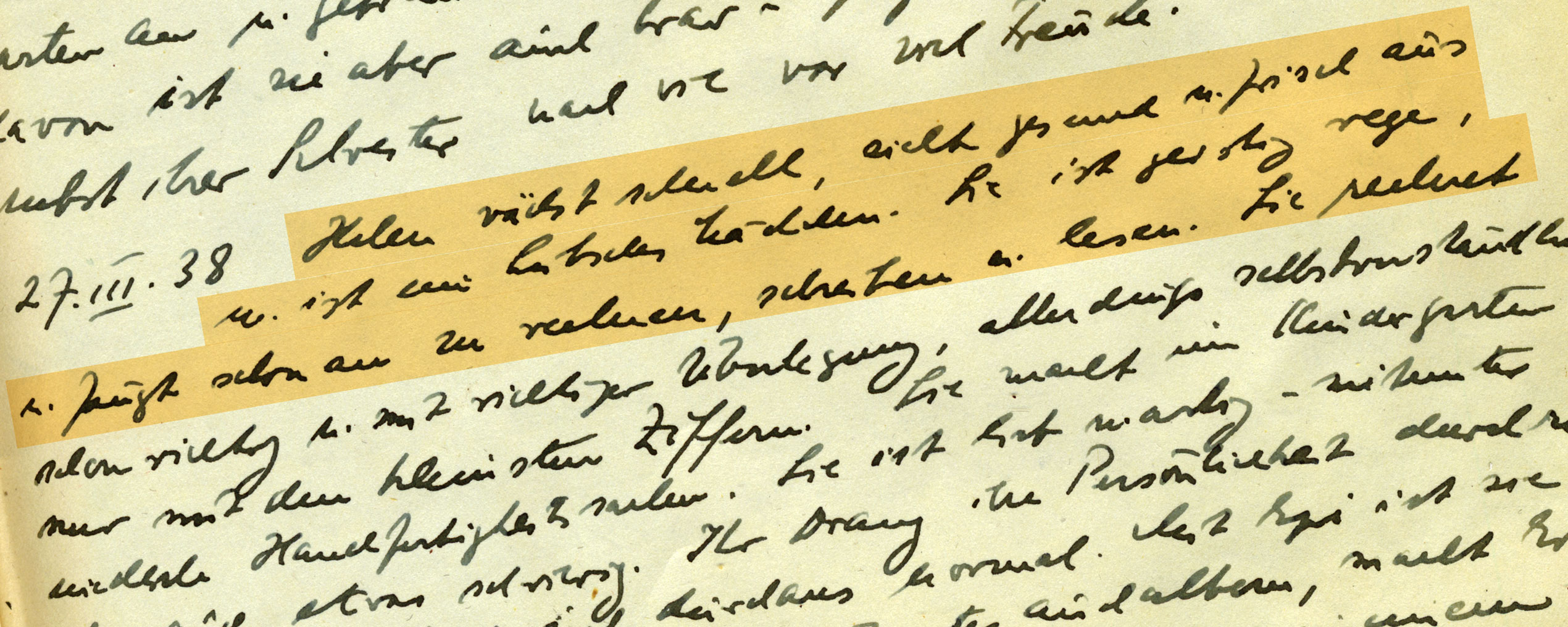

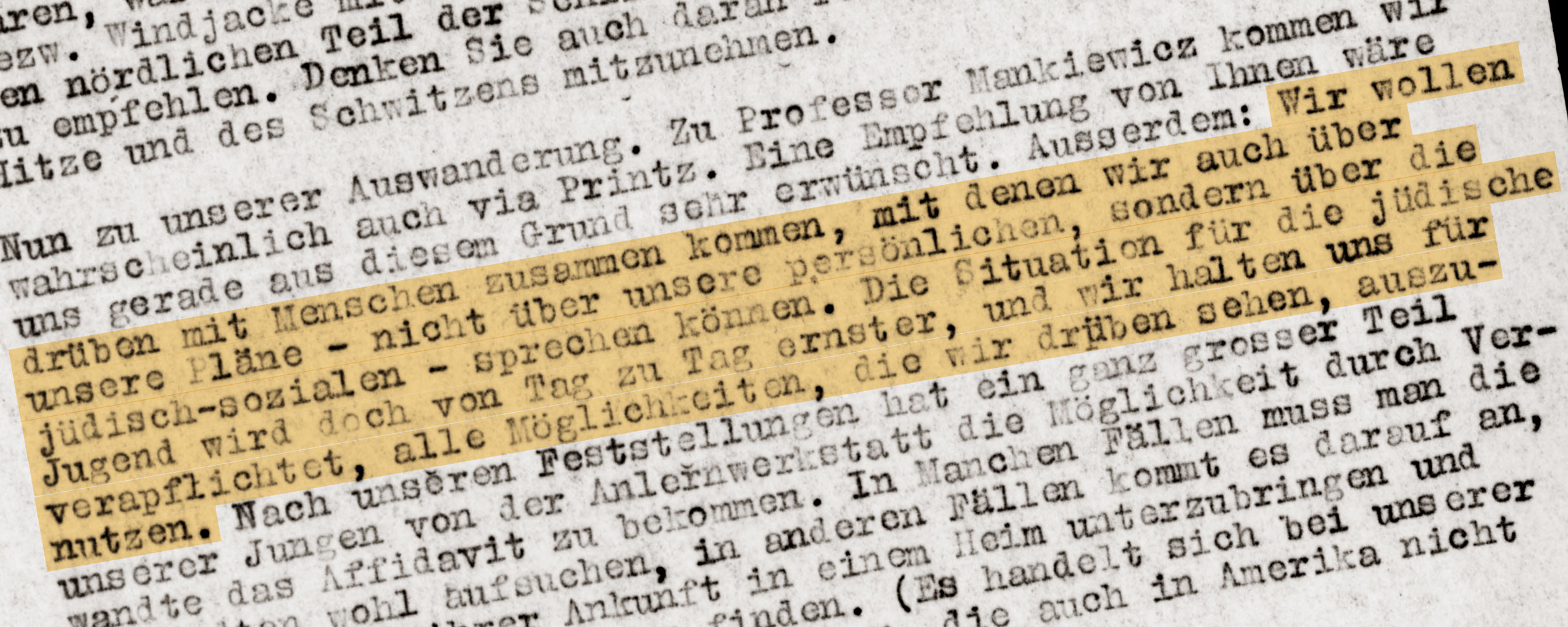

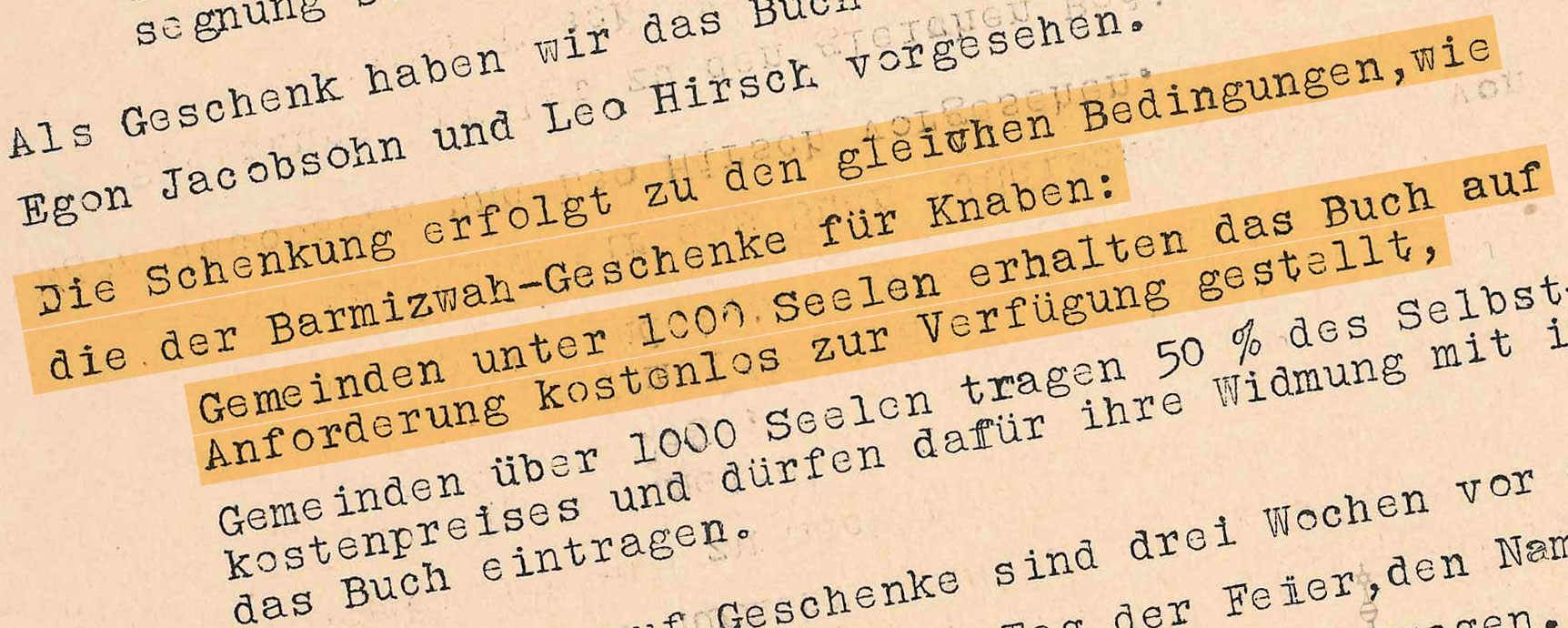

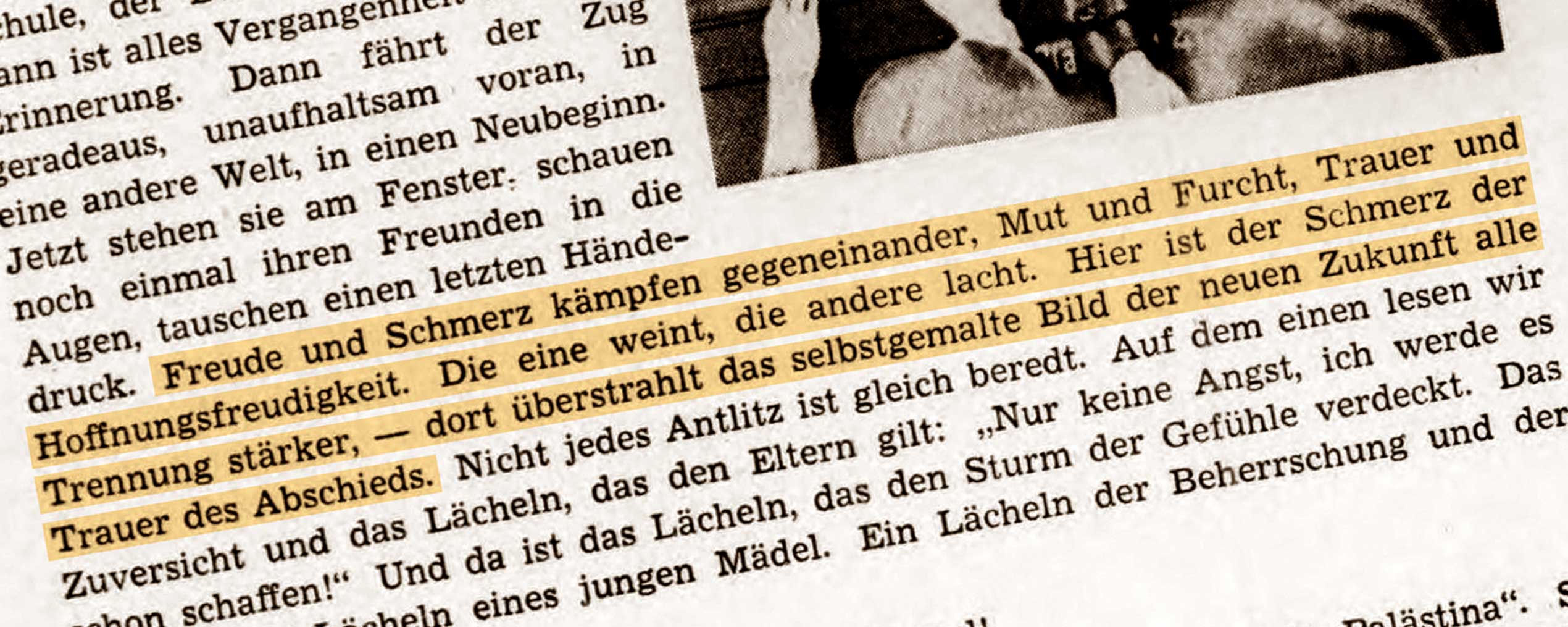

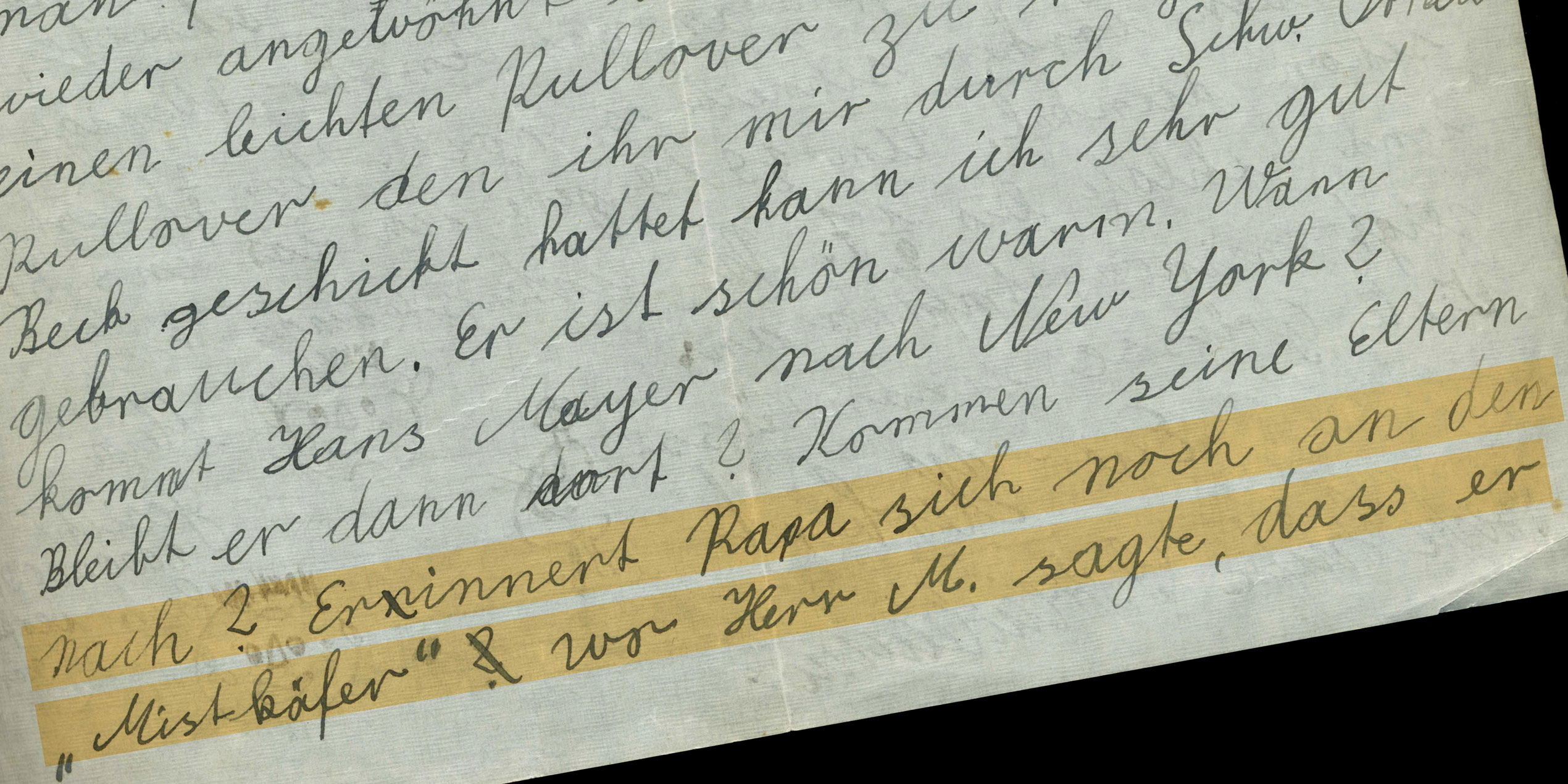

Gusty Bendheim, a Berliner, had never met the American branch of her family. As a 42-year-old divorcee, she had no other choice but to turn to her overseas relatives. She asked these quasi-strangers for help facilitating emigration for herself and her children, Ralph (13) and Margot (17). Gusty was an enterprising sort: by the time she got married to Arthur Bendheim, a businessman from Frankfurt/Main, around 1920, she had established three button stores. After the wedding, Arthur took over management and Gusty became a housewife. In spite of the increasingly alarming anti-Jewish measures taken by the Nazi government, Arthur was not willing to leave. After the couple’s divorce in 1937, Gusty took matters into her own hands. In this August 14th, 1938 letter to her unknown relatives, in addition to her request for help, she states that her former husband is ready to pay the costs of travel for her and their children to the United States.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Margot Friedlander Collection, AR 11397

Original:

Box 1, folder 1

Source available in English