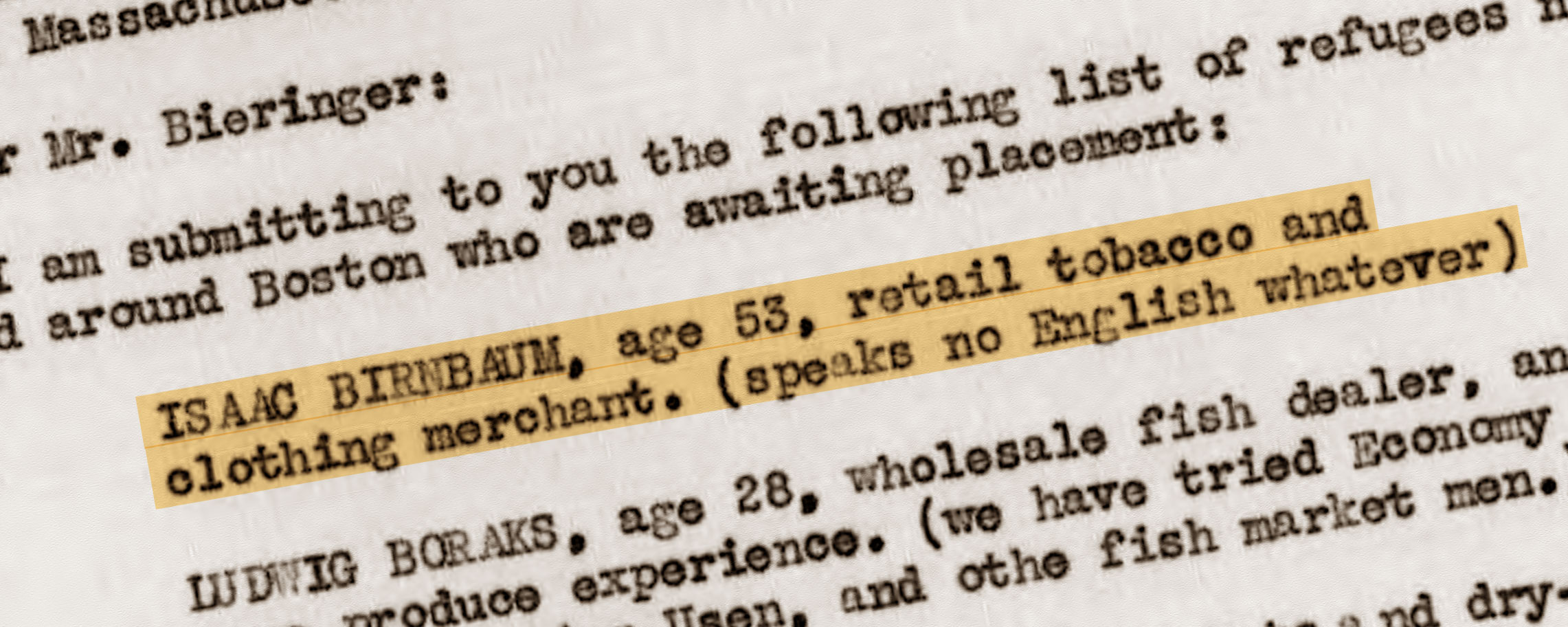

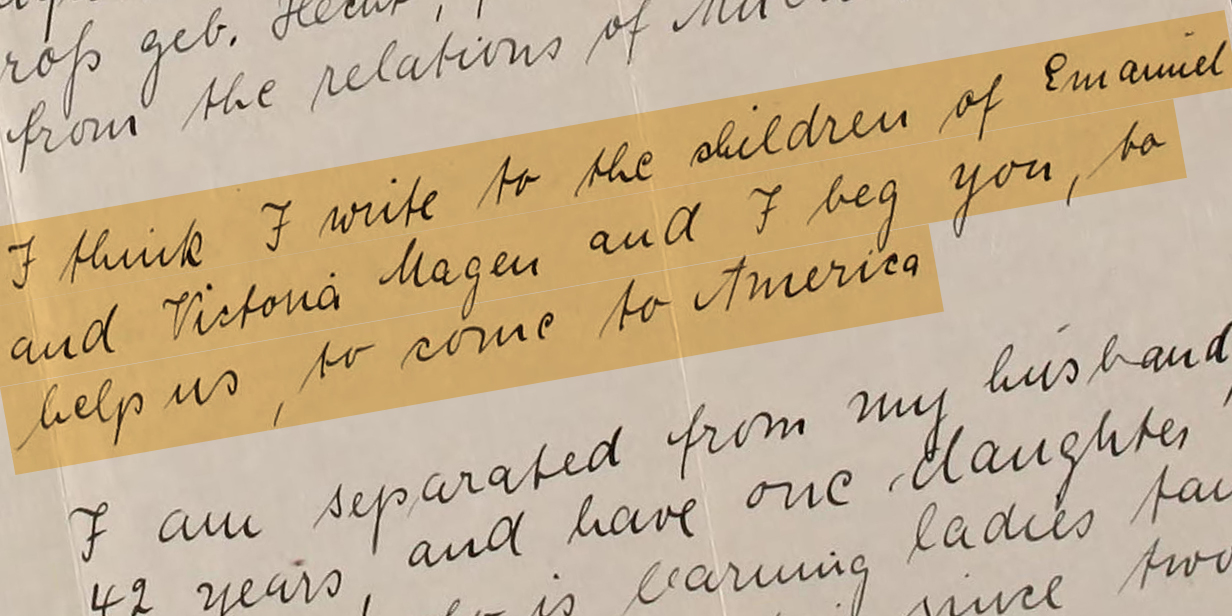

What will he live on in America?

Refugee with no English and few skills needs help finding work

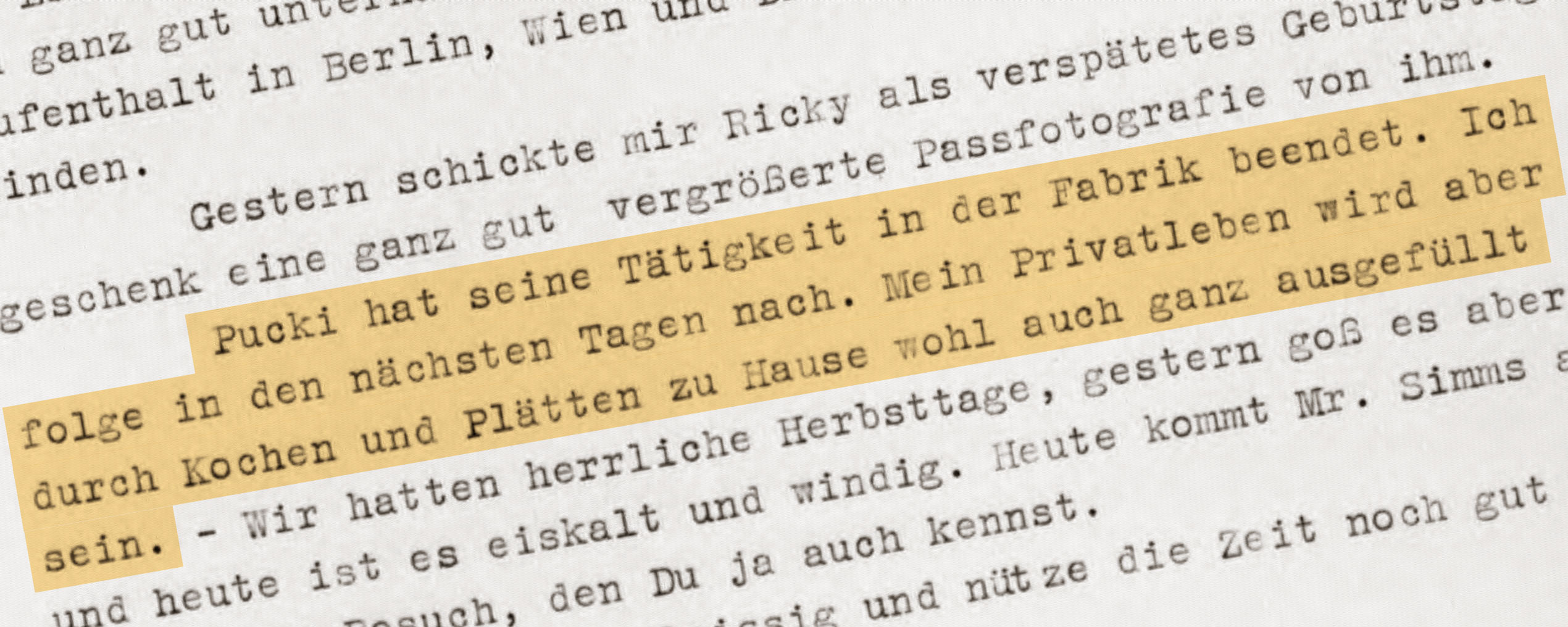

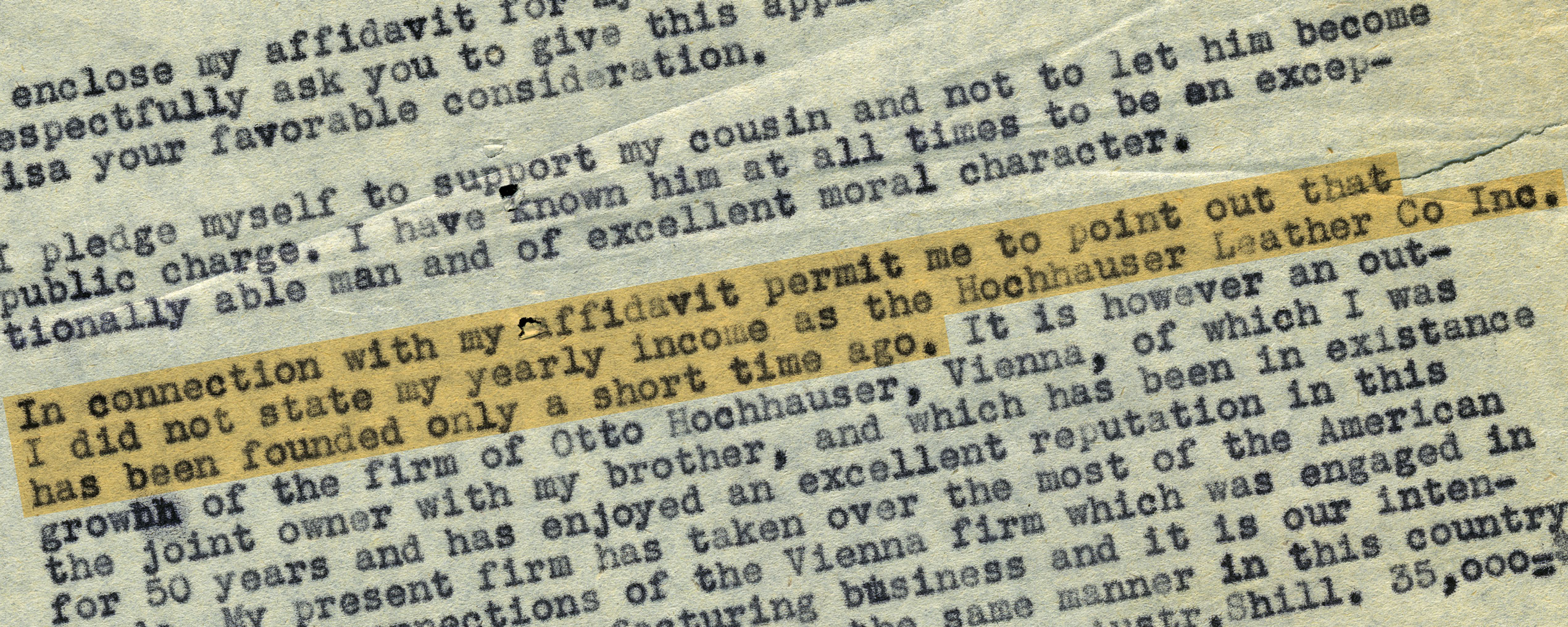

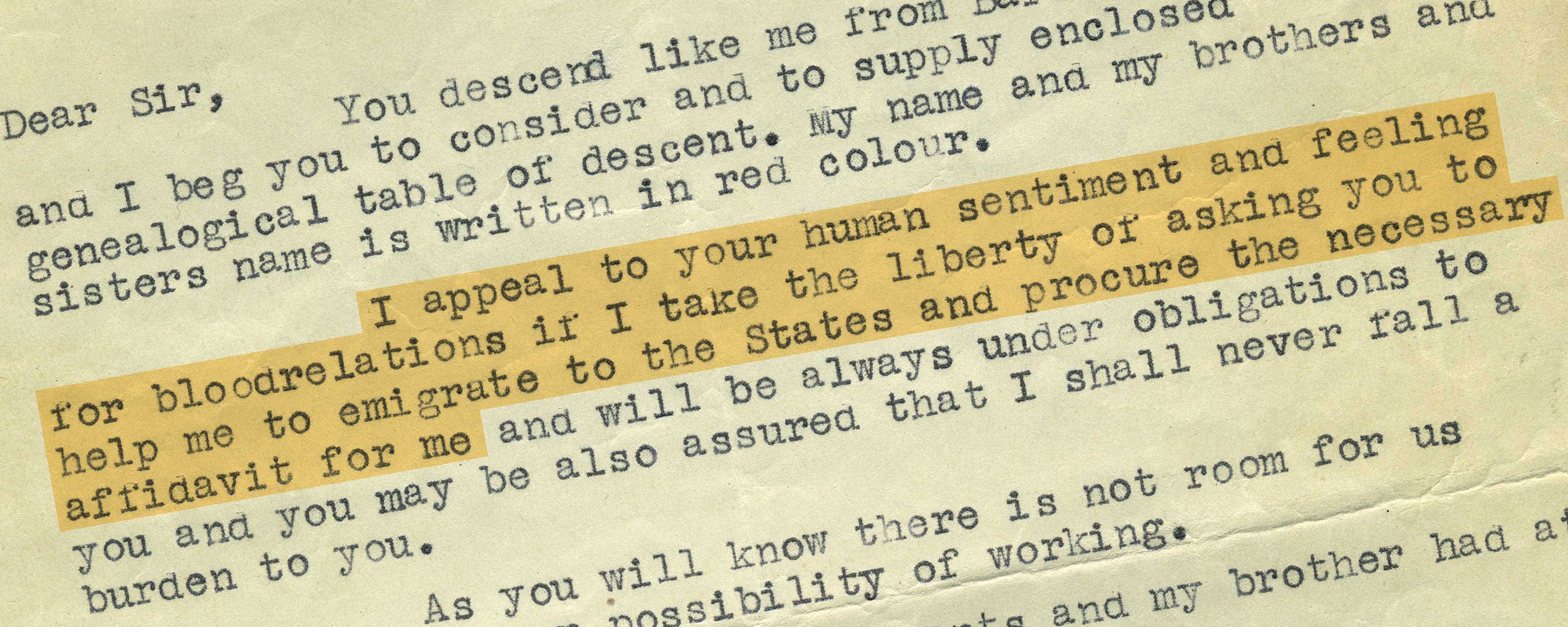

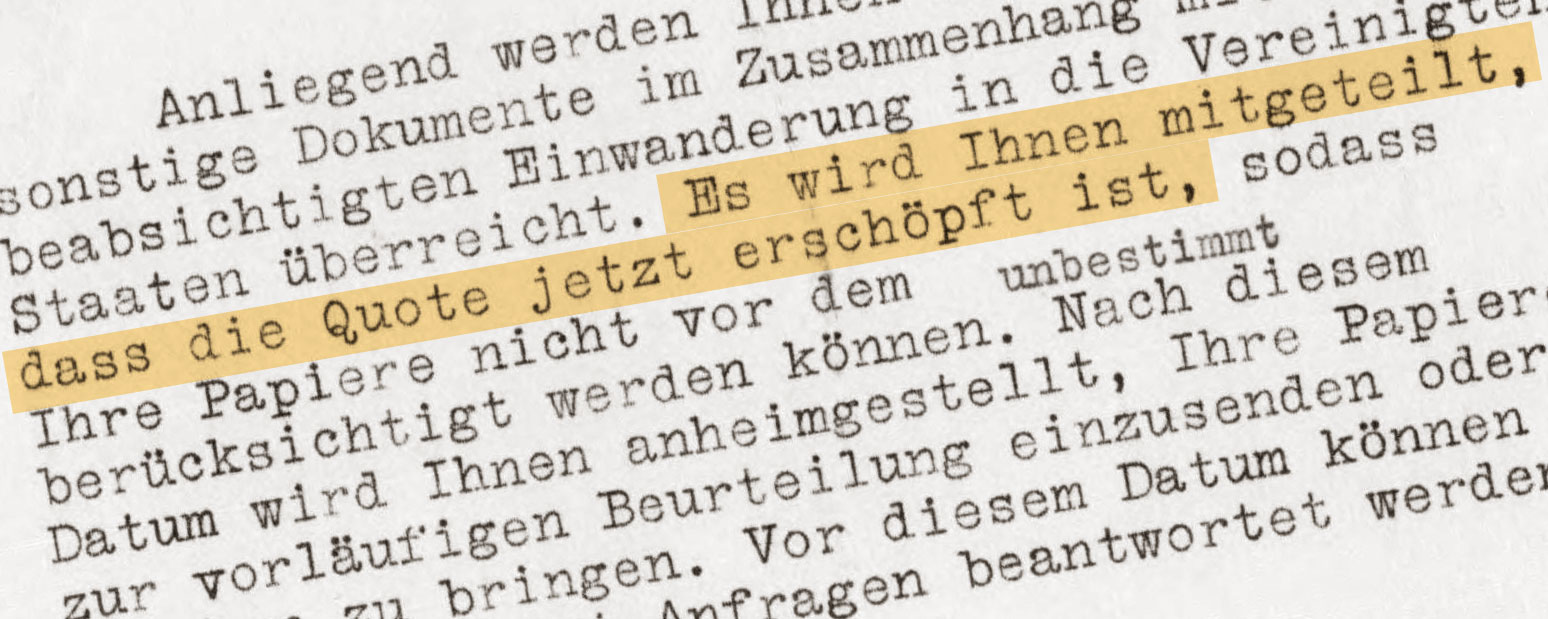

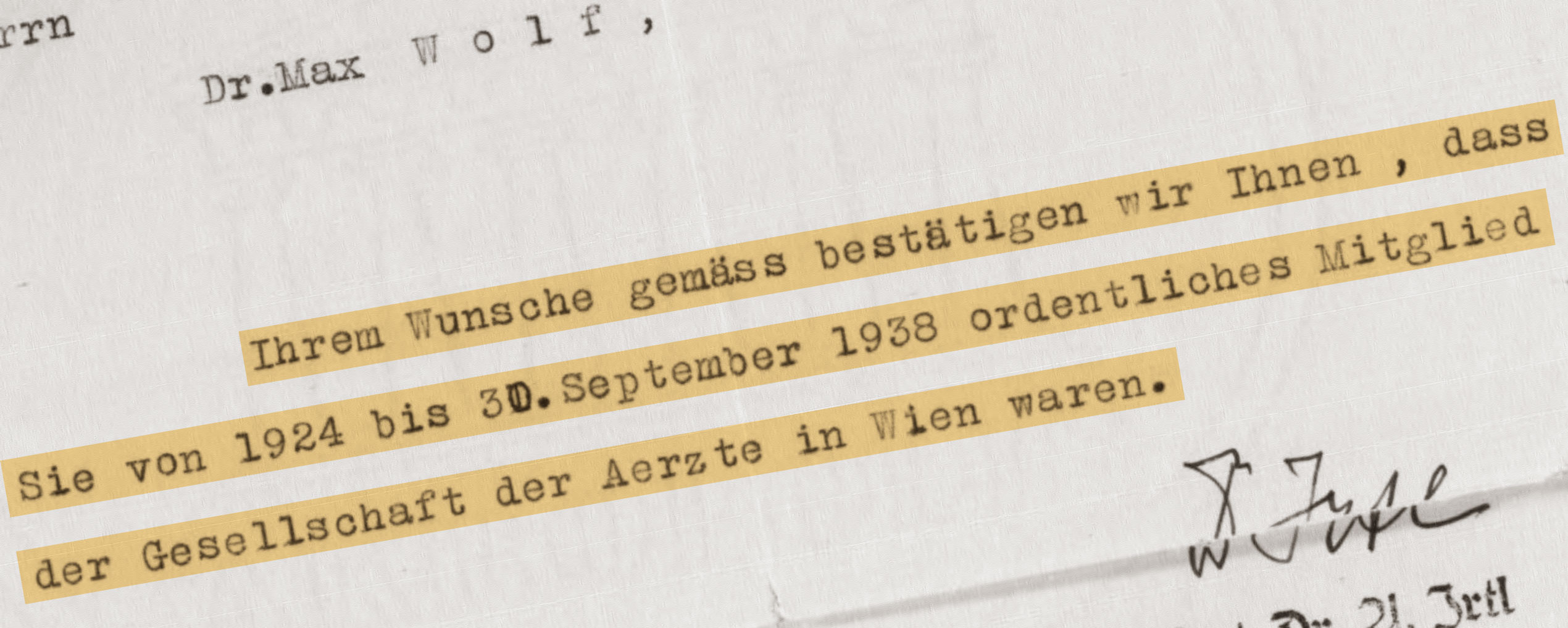

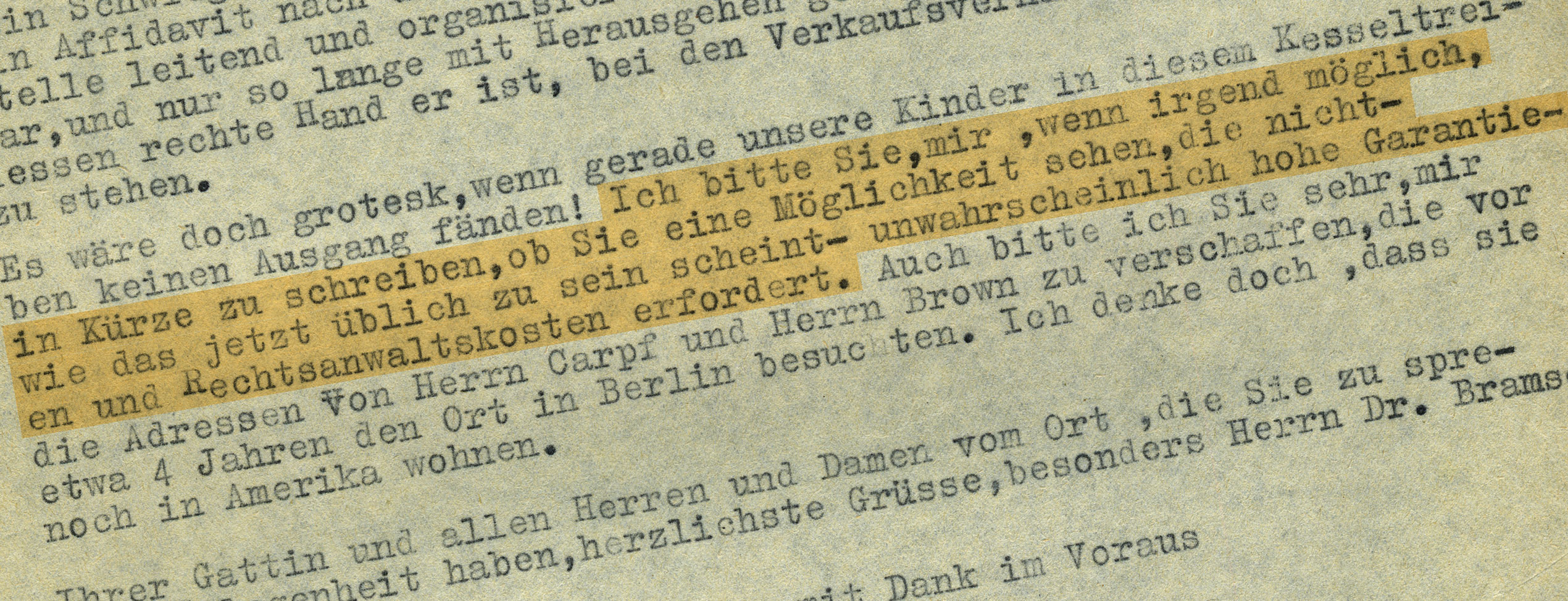

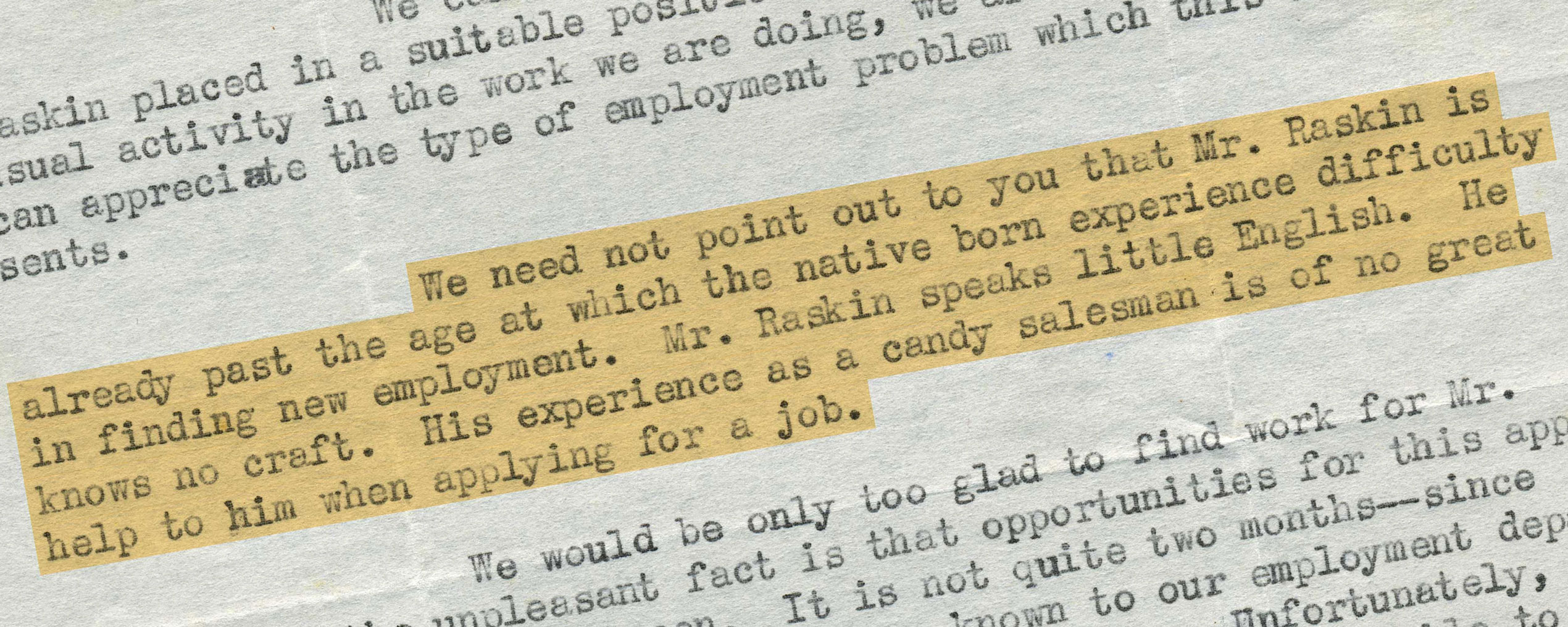

“We need not point out to you that Mr. Raskin is already past the age at which the native born experience difficulty in finding new employment. Mr. Raskin speaks little English. He knows no craft. His experience as a candy salesman is of no great help to him when applying for a new job.”

NEW YORK/BOSTON

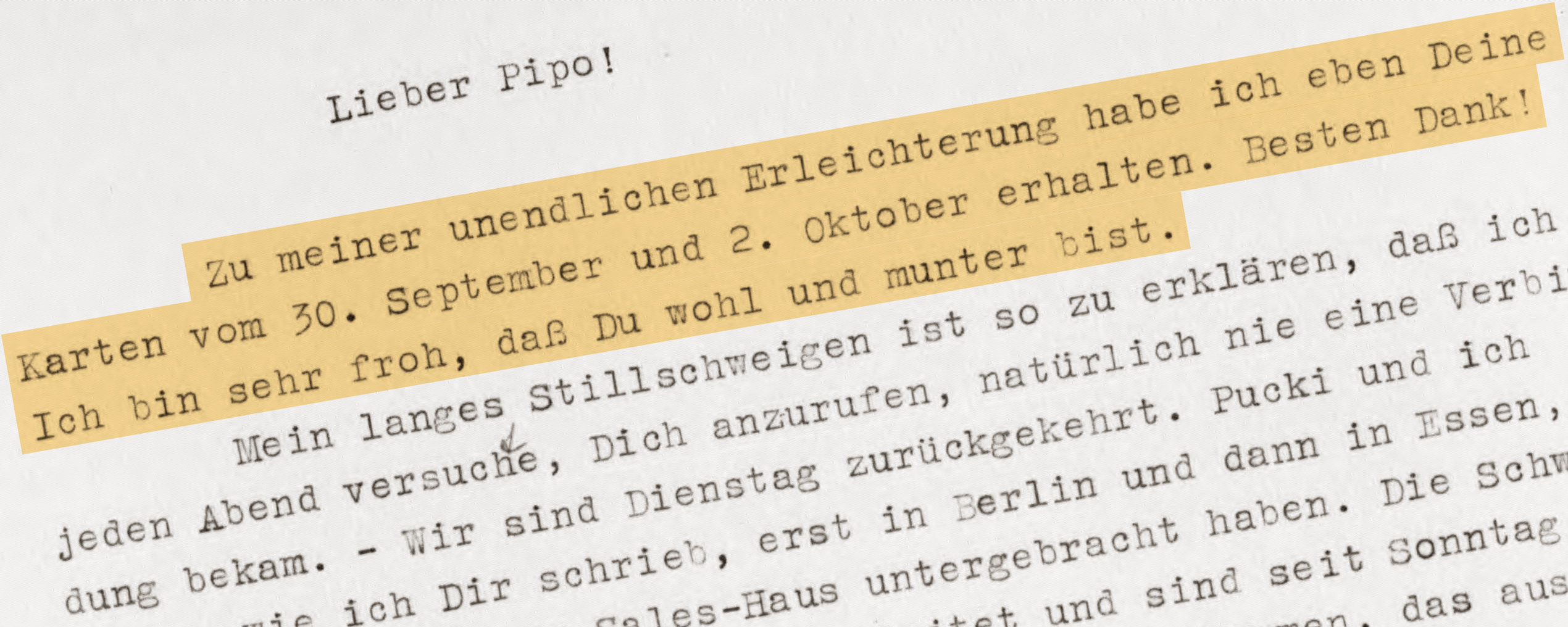

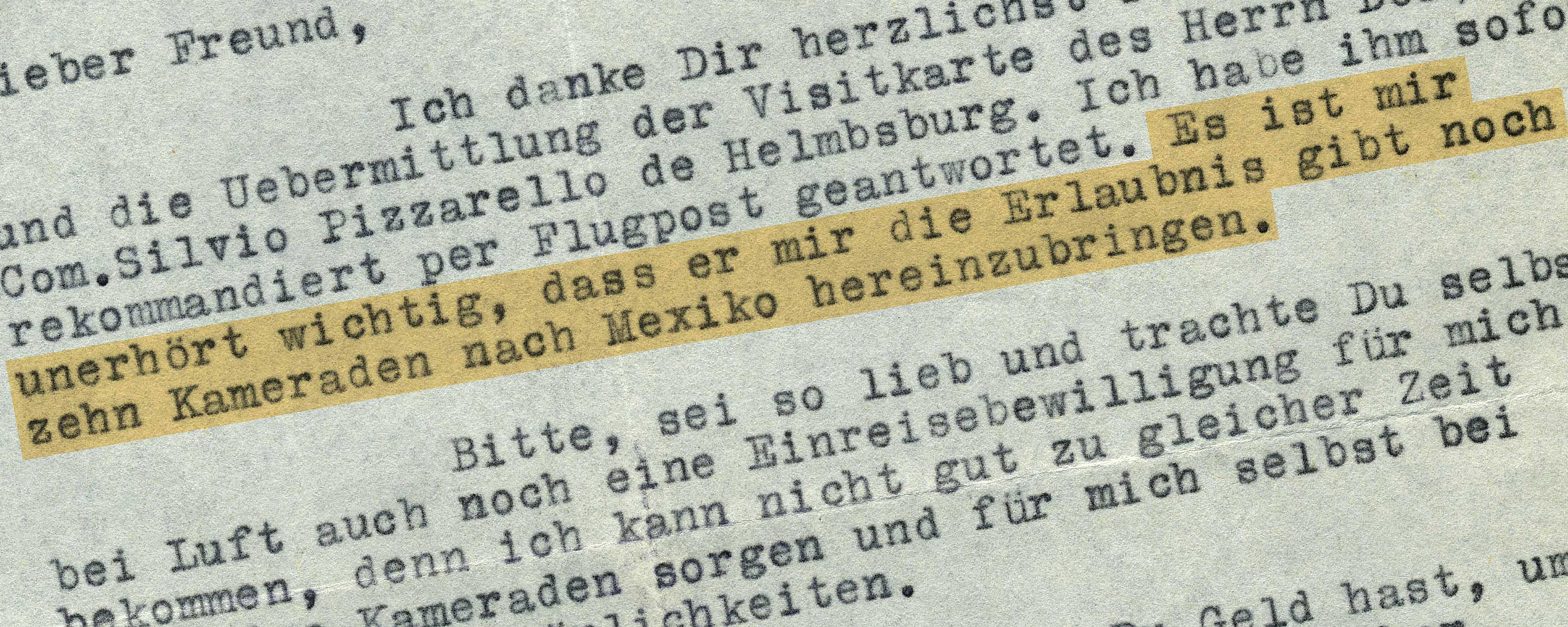

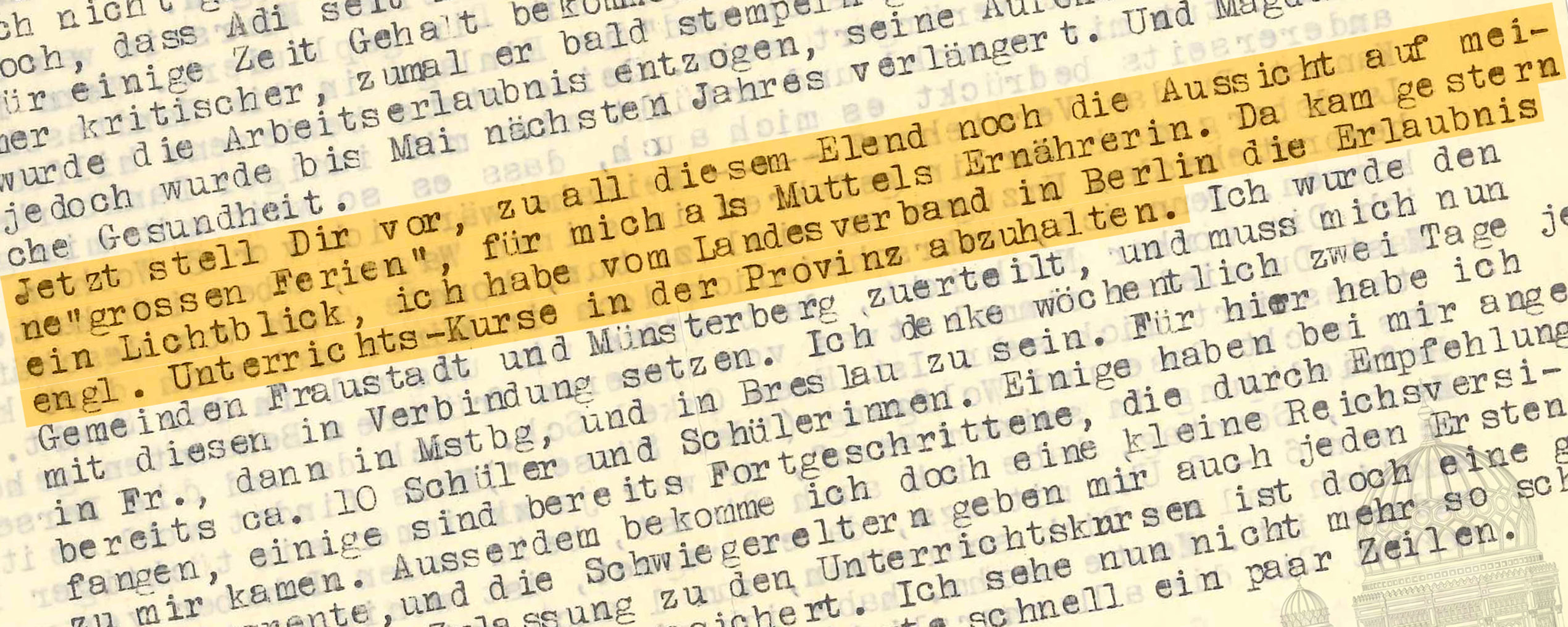

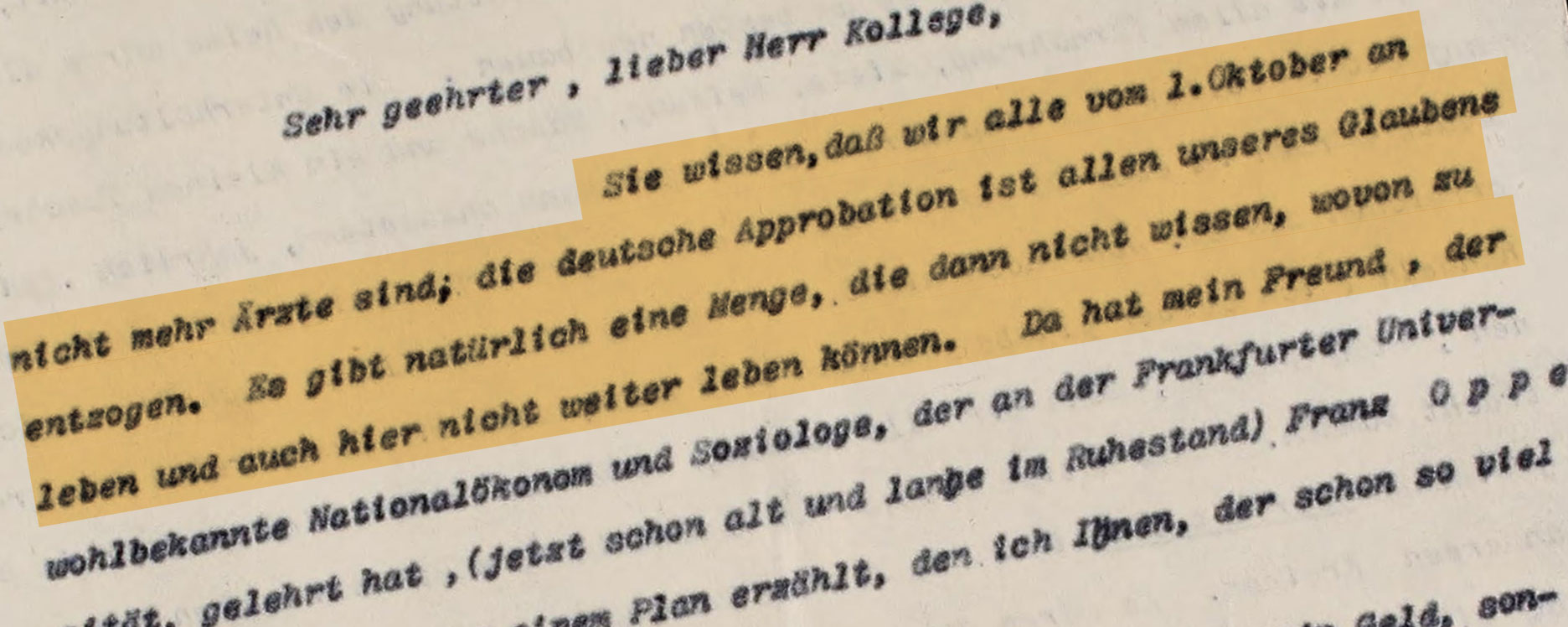

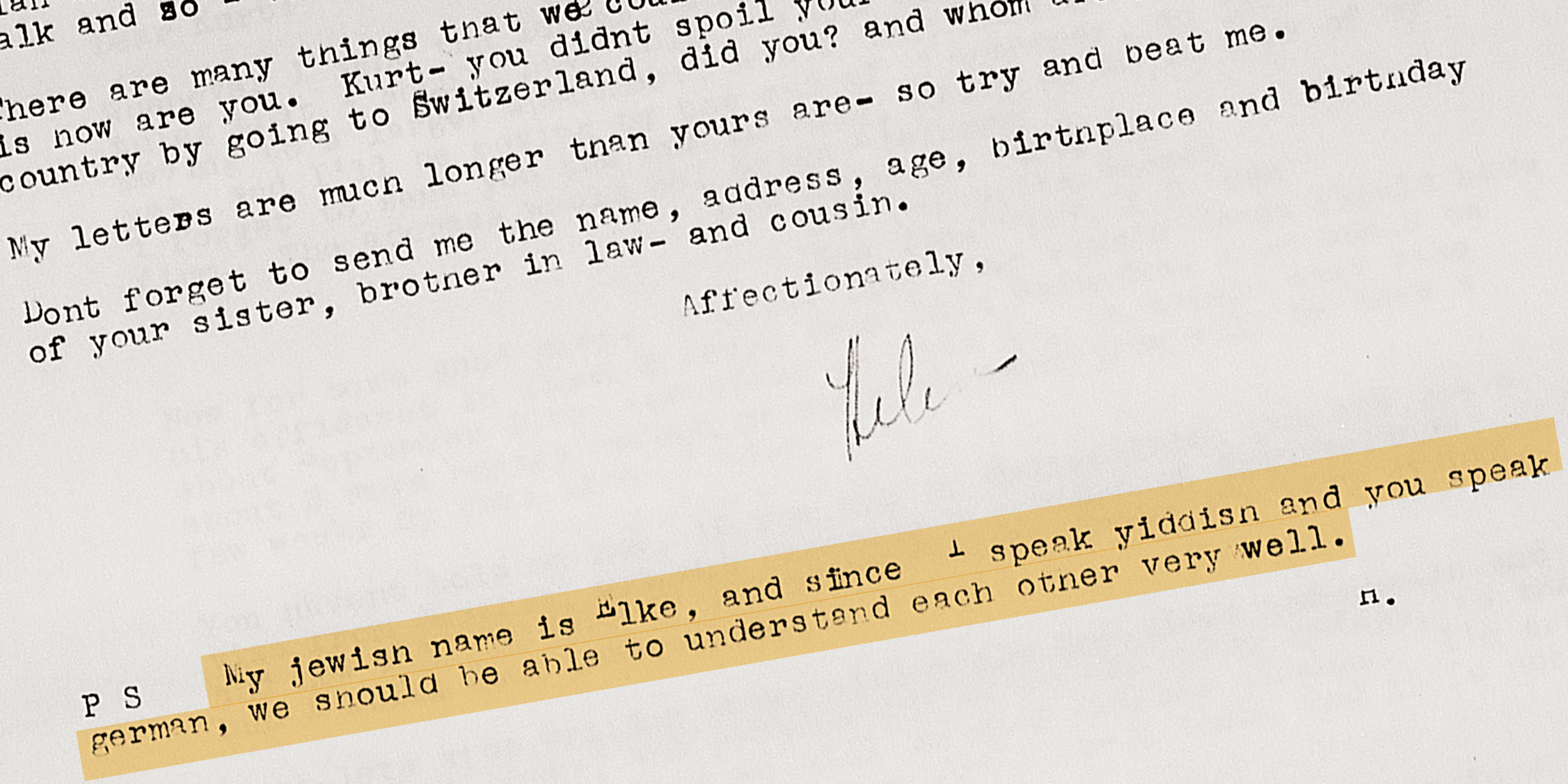

Since the early 1880s, federal immigration law in the US included a provision seeking to keep out people likely to become a “public charge.” Under the impact of the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover reinforced the ban in 1930. Aid organizations were hard pressed to find employment for the newcomers: on October 26, a representative of the Employment Department of the Greater New York Coordinating Committee for German Refugees explains to Willy Nordwind of the Boston Committee for Refugees the challenges of finding work for a man who had managed to enter the country but barely spoke any English and had no work experience to boast save as a candy salesman. Nevertheless, the representative promises to continue his efforts on the immigrant’s behalf.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Willy Nordwind Collection, AR 10551

Original:

Source available in English

Chronology of major events in 1938

The Polenaktion

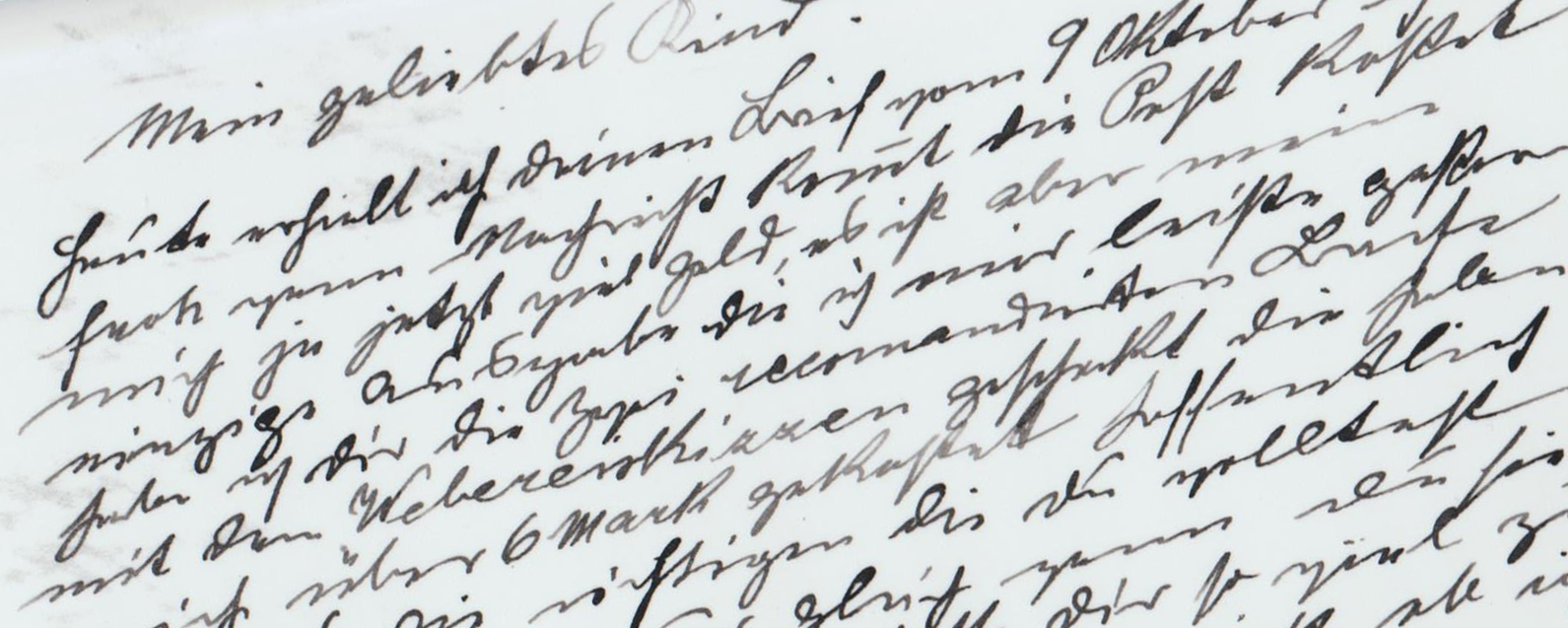

A photograph capturing the "Polenaktion".

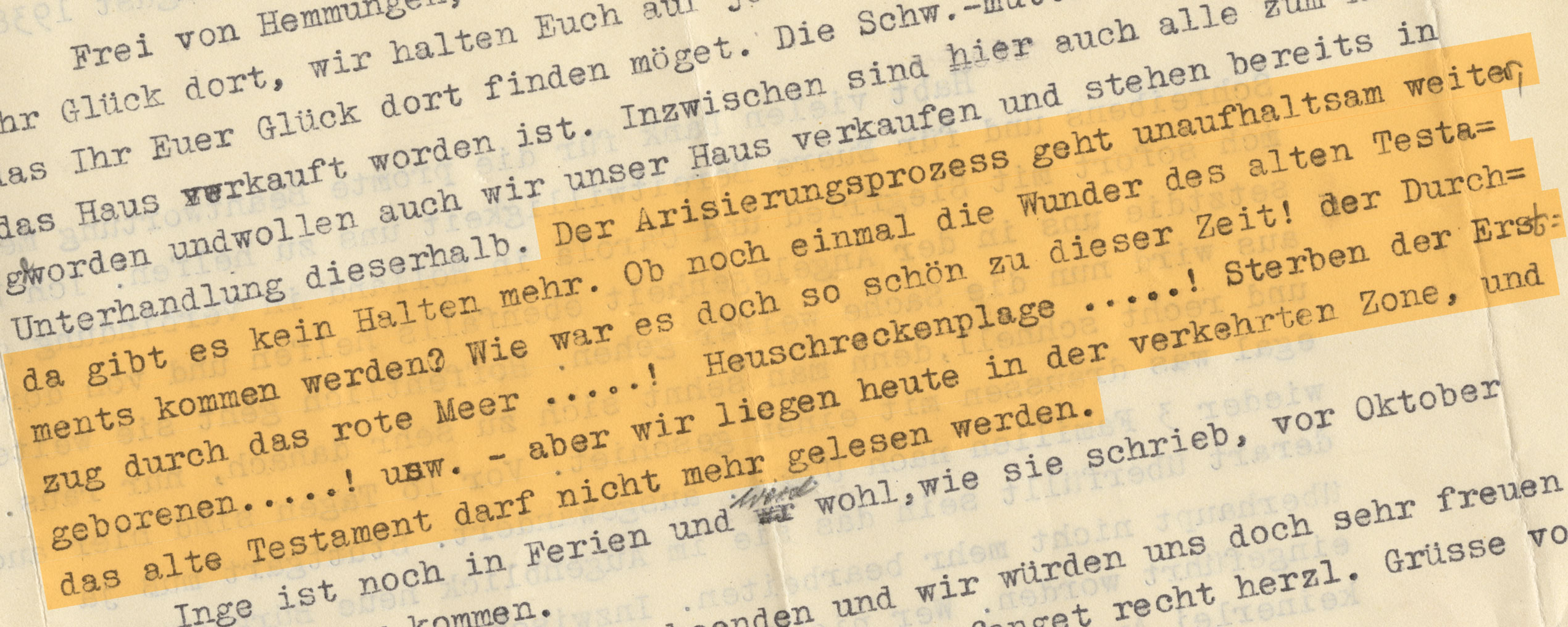

The National Socialists deport about 17,000 Polish Jews from the German Reich. The mass deportation is referred to as the Polenaktion (Polish Measure), and it is a new high water mark in anti-Jewish discrimination. The Polish parliament issued laws in March and October that threatened to revoke the citizenship of Polish citizens living abroad. For example, passports that were issued abroad were declared invalid starting October 30, unless they were inspected and approved by the Polish Consulates. Through these measures, the Polish government hoped to prevent the mass emigration of tens of thousands of Polish Jews from the German Reich to Poland. When the German Embassy in Warsaw learned of the invalidation of Polish passports in October, the National Socialists responded with deportation orders, mass arrests, and transports to the Polish border.

View chronology of major events in 1938