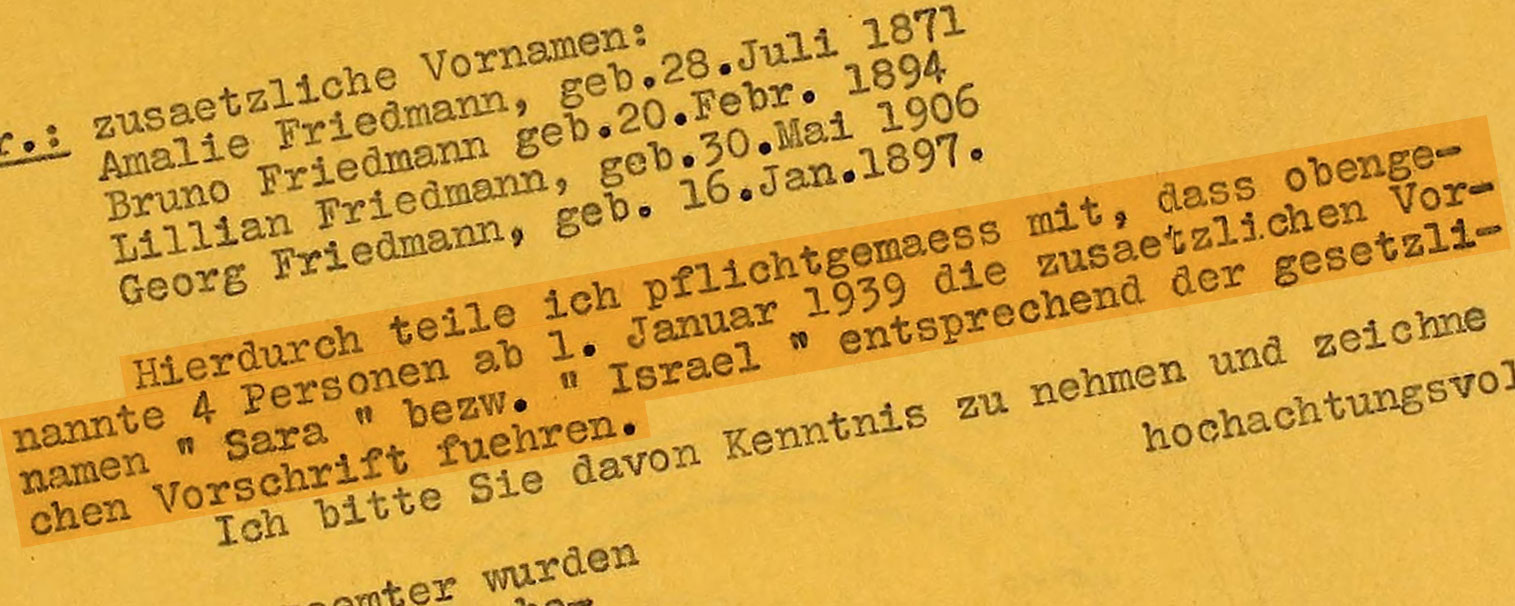

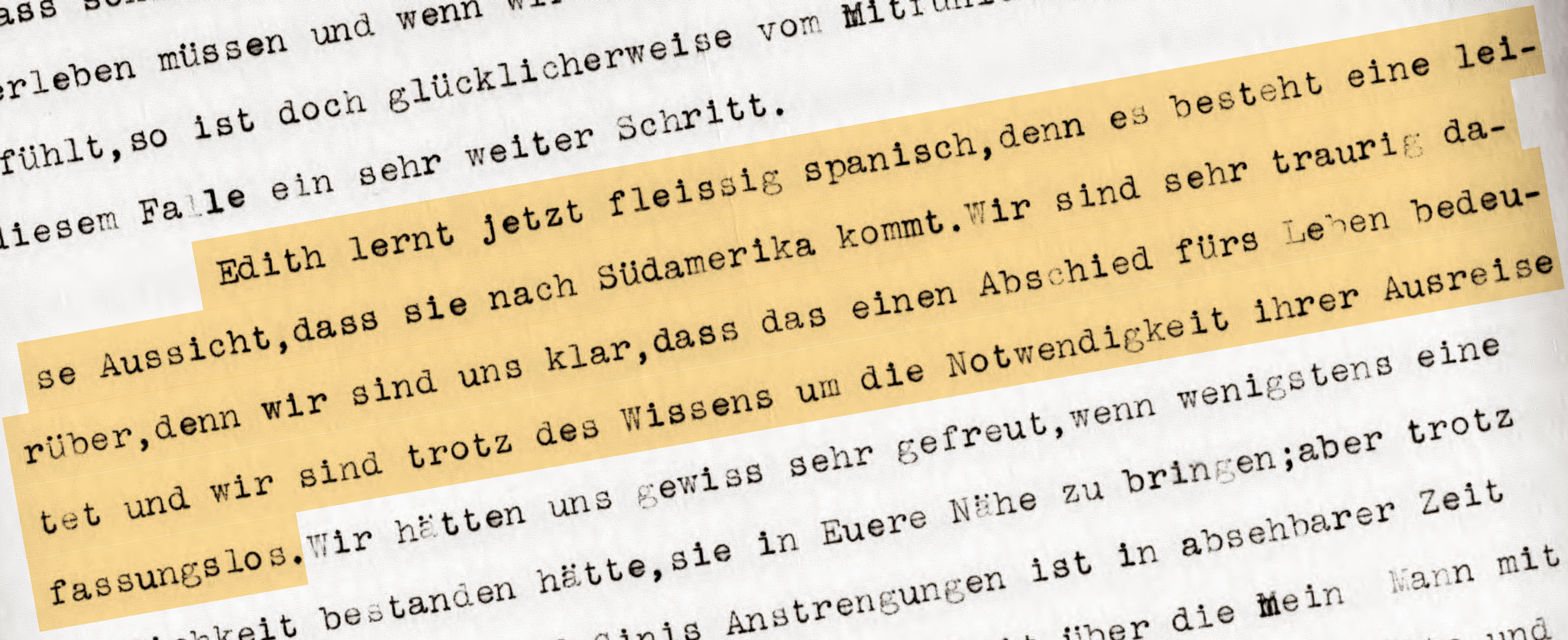

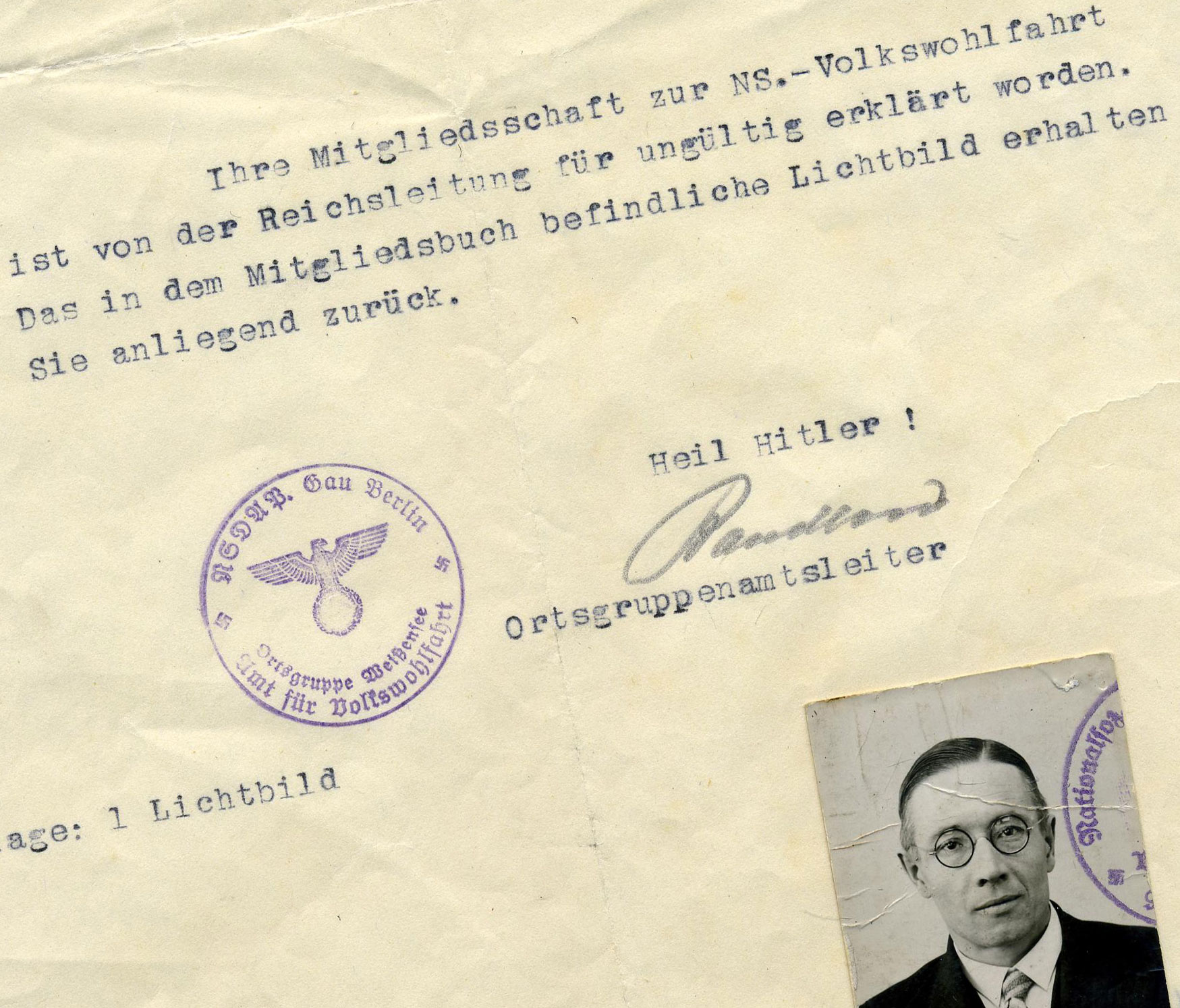

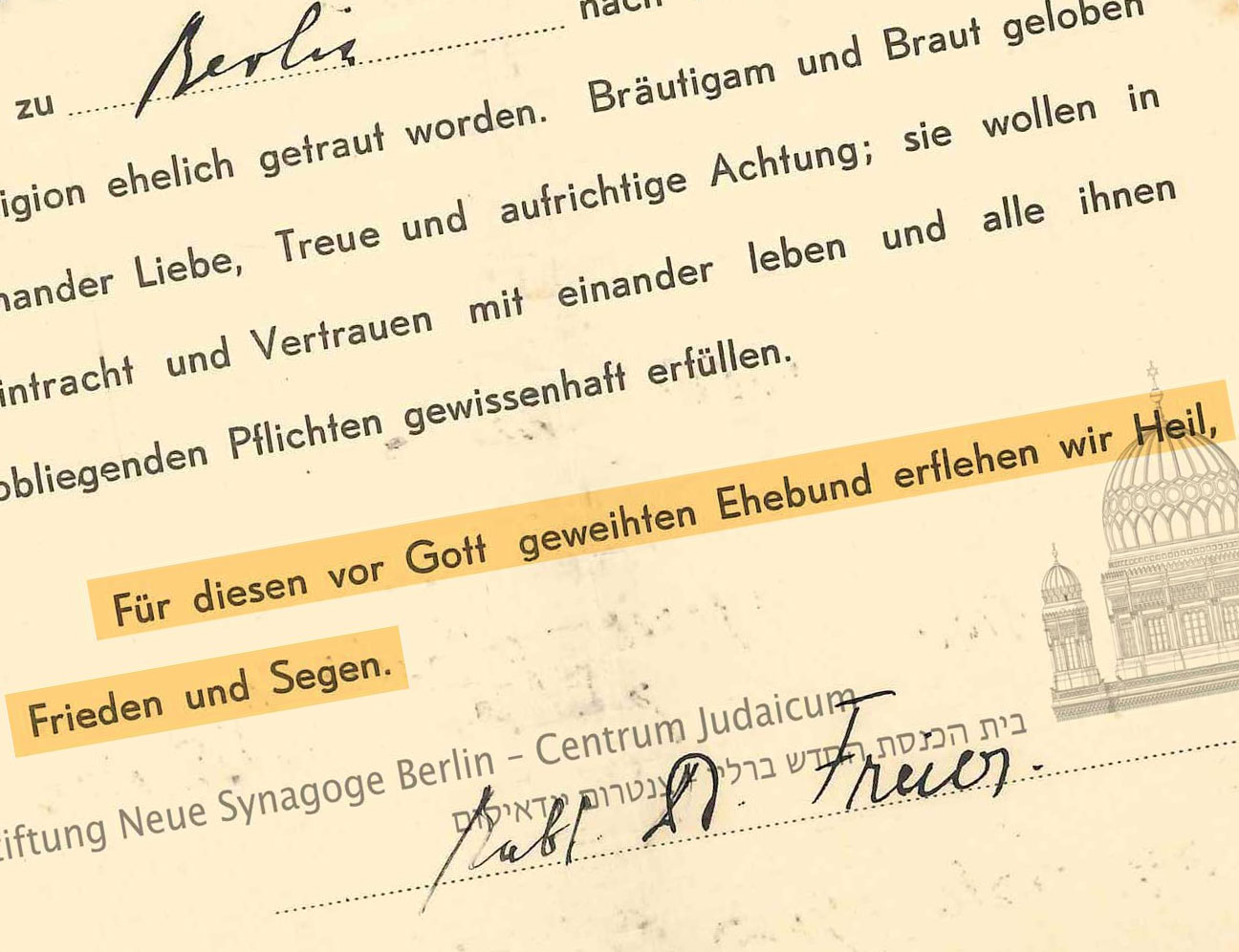

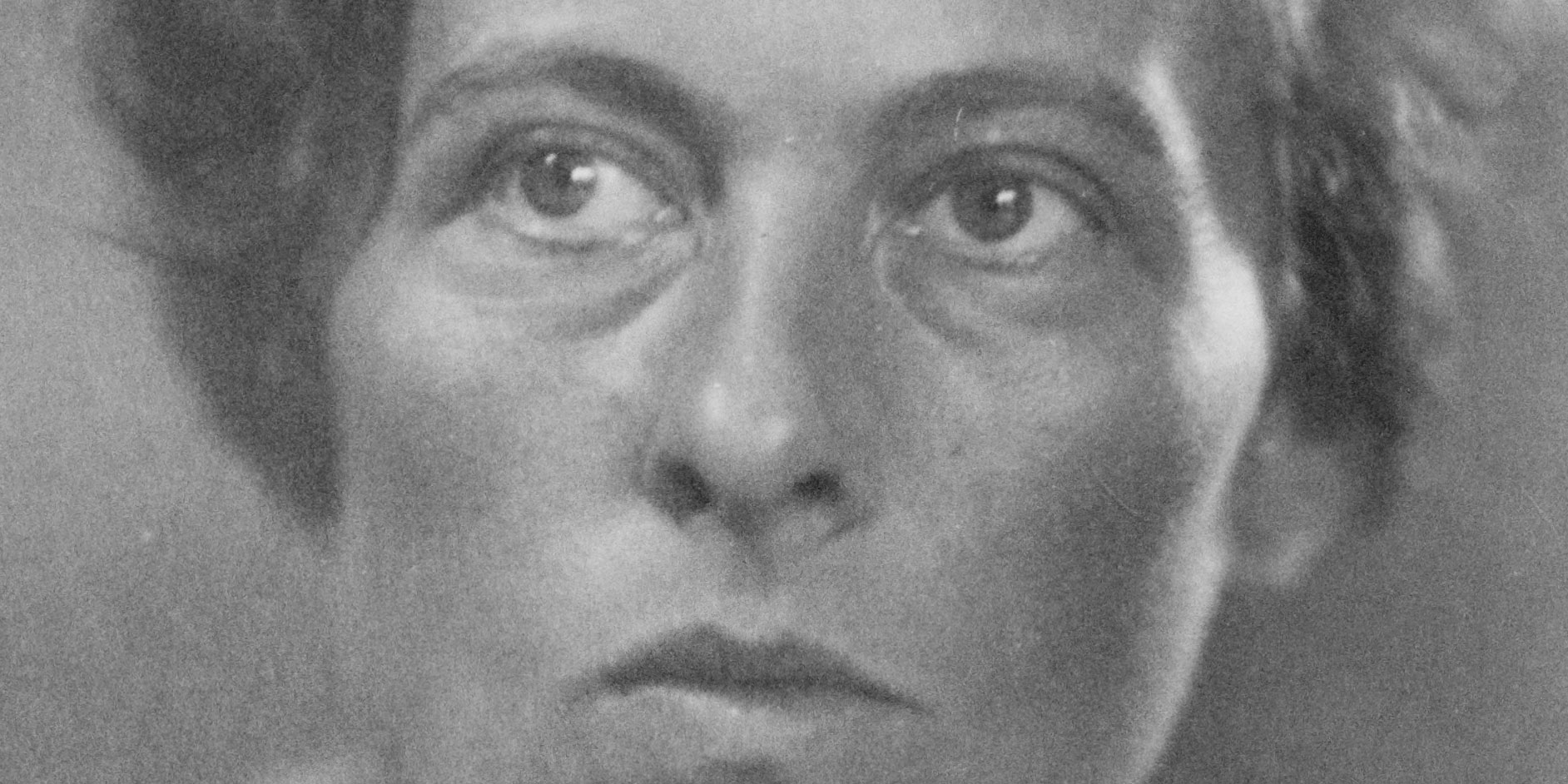

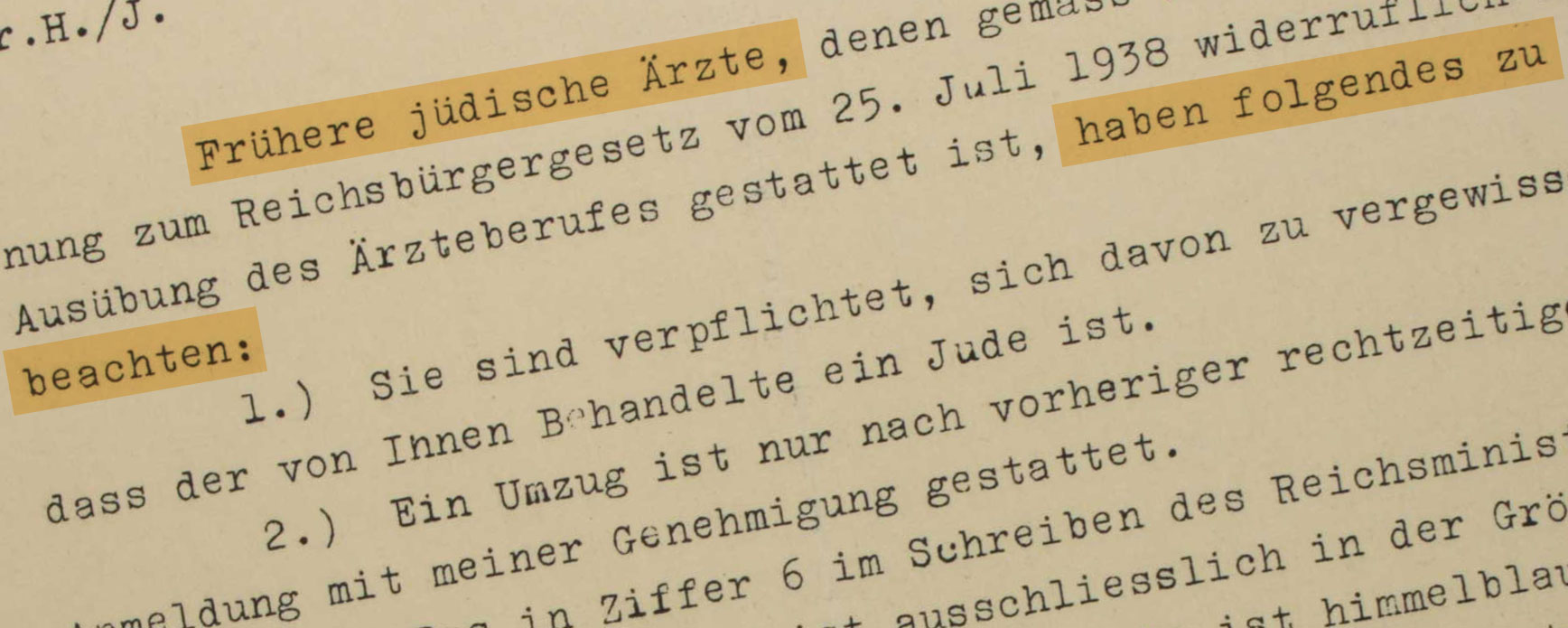

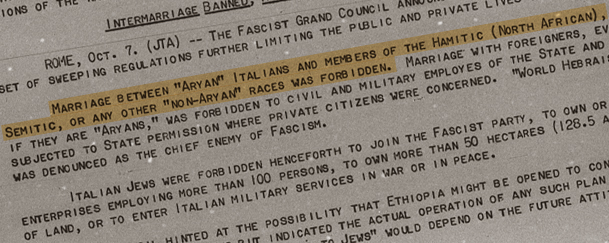

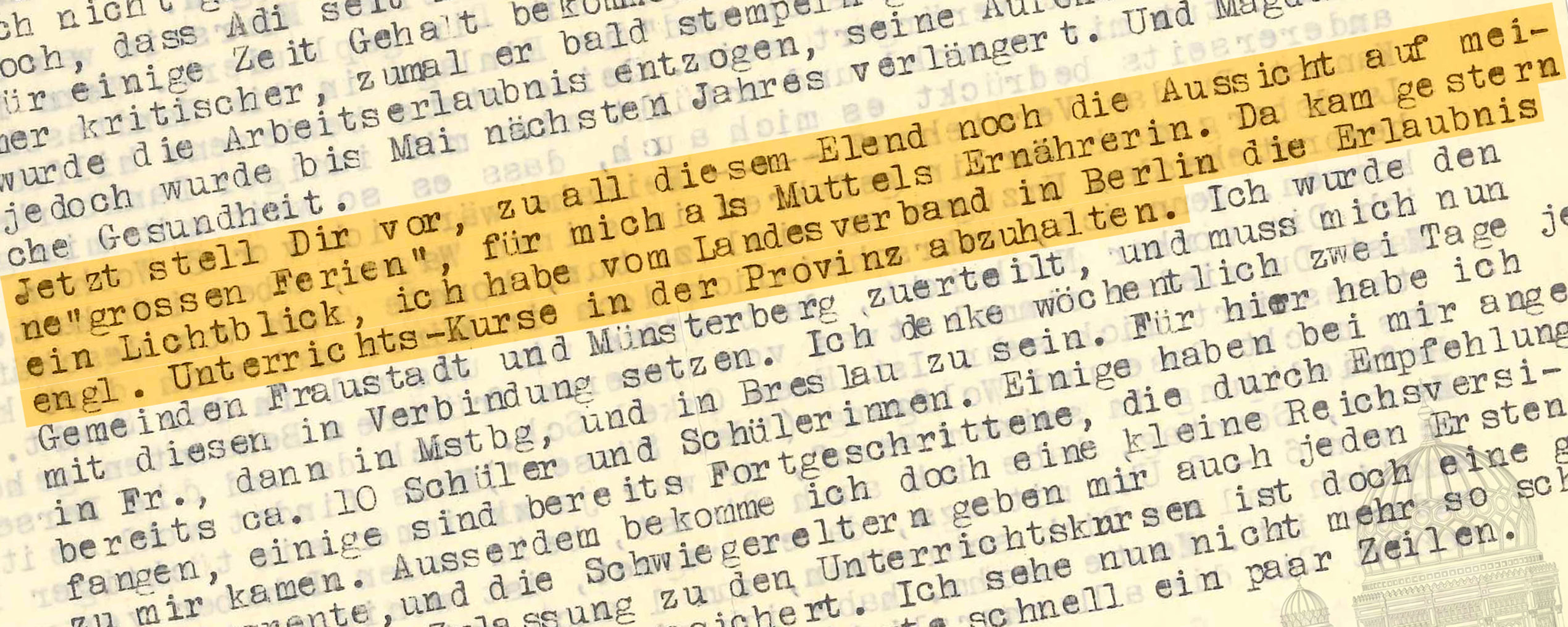

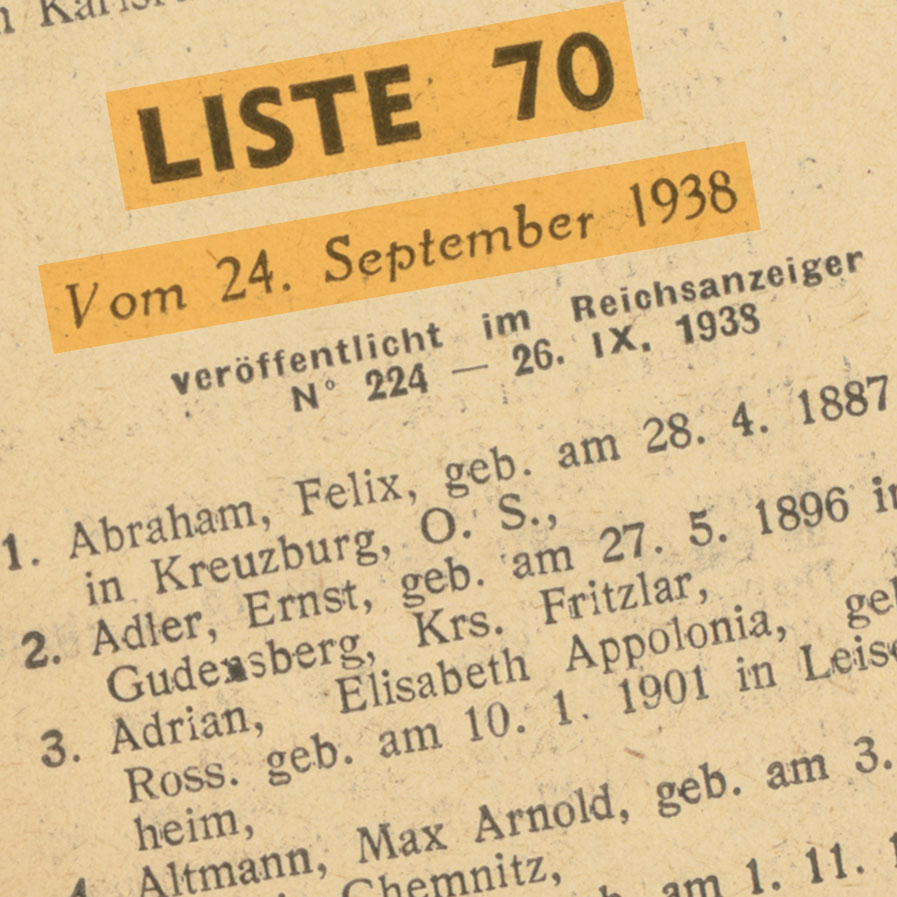

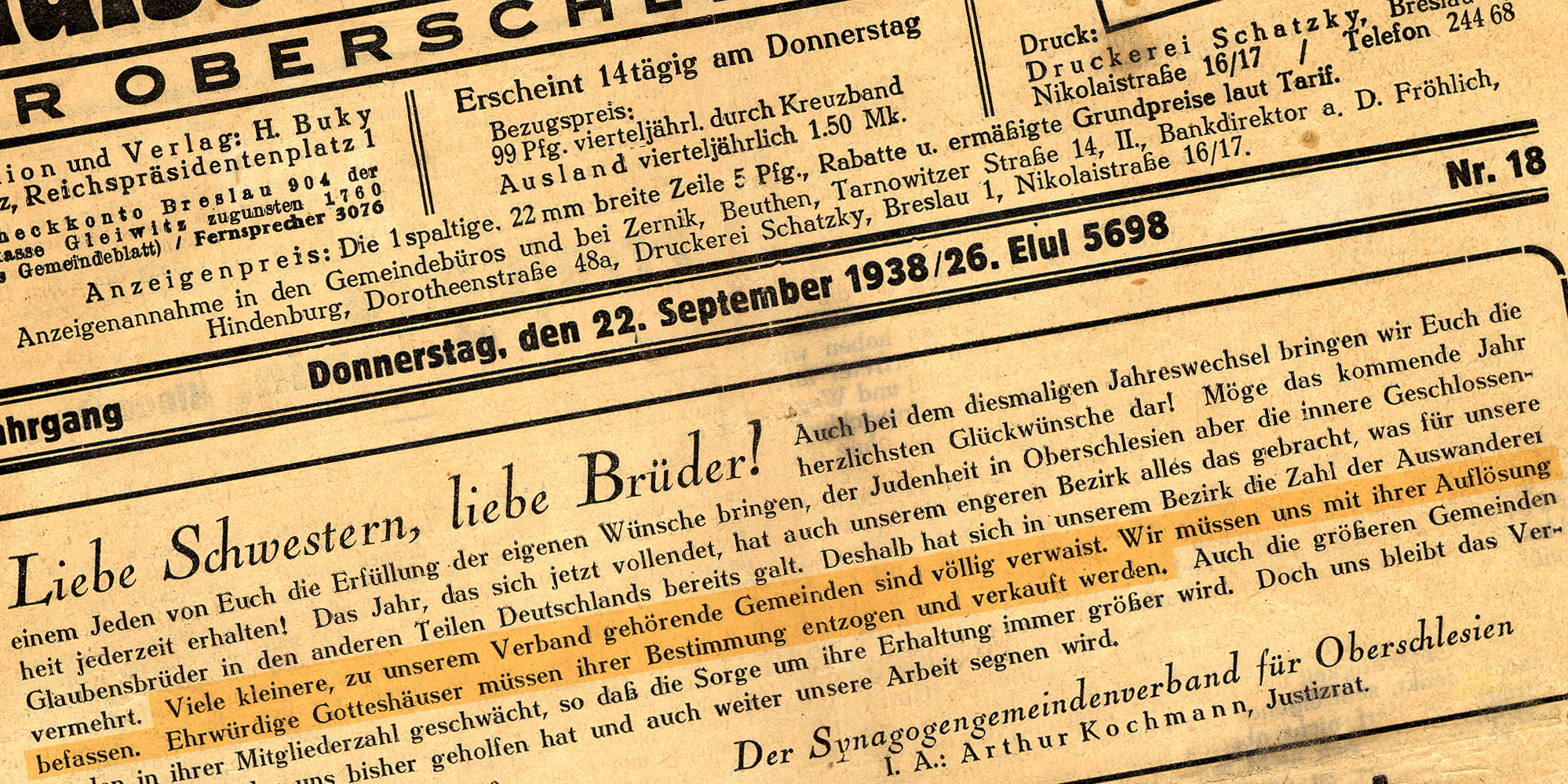

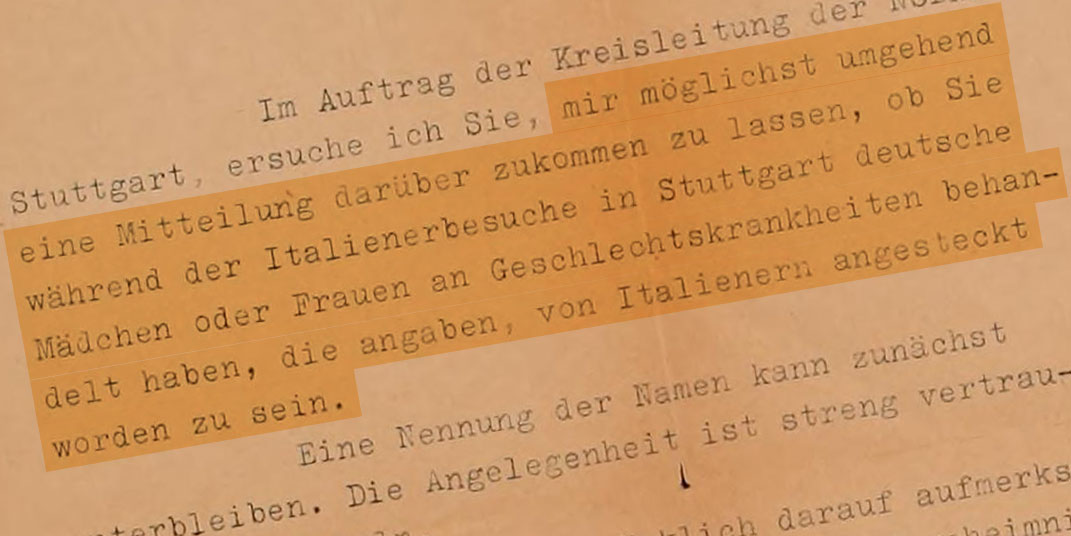

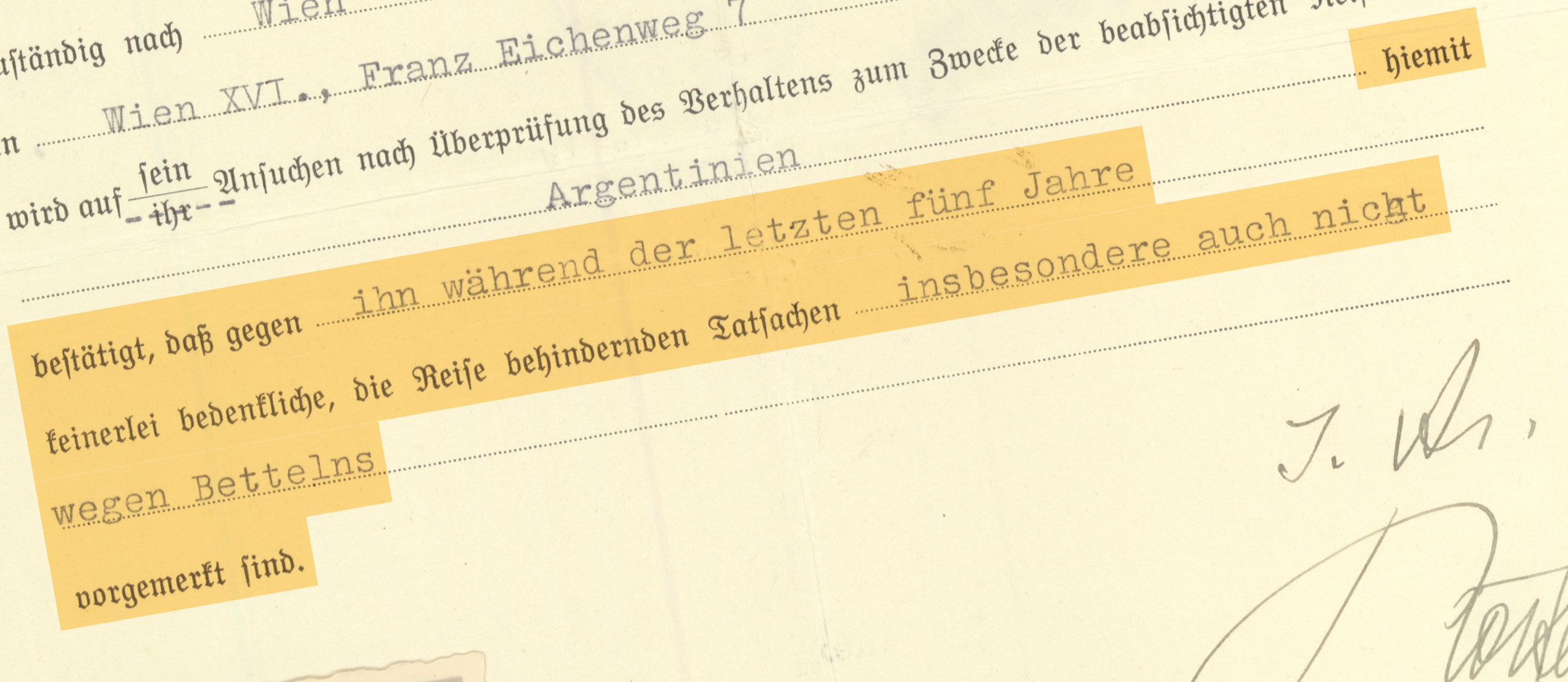

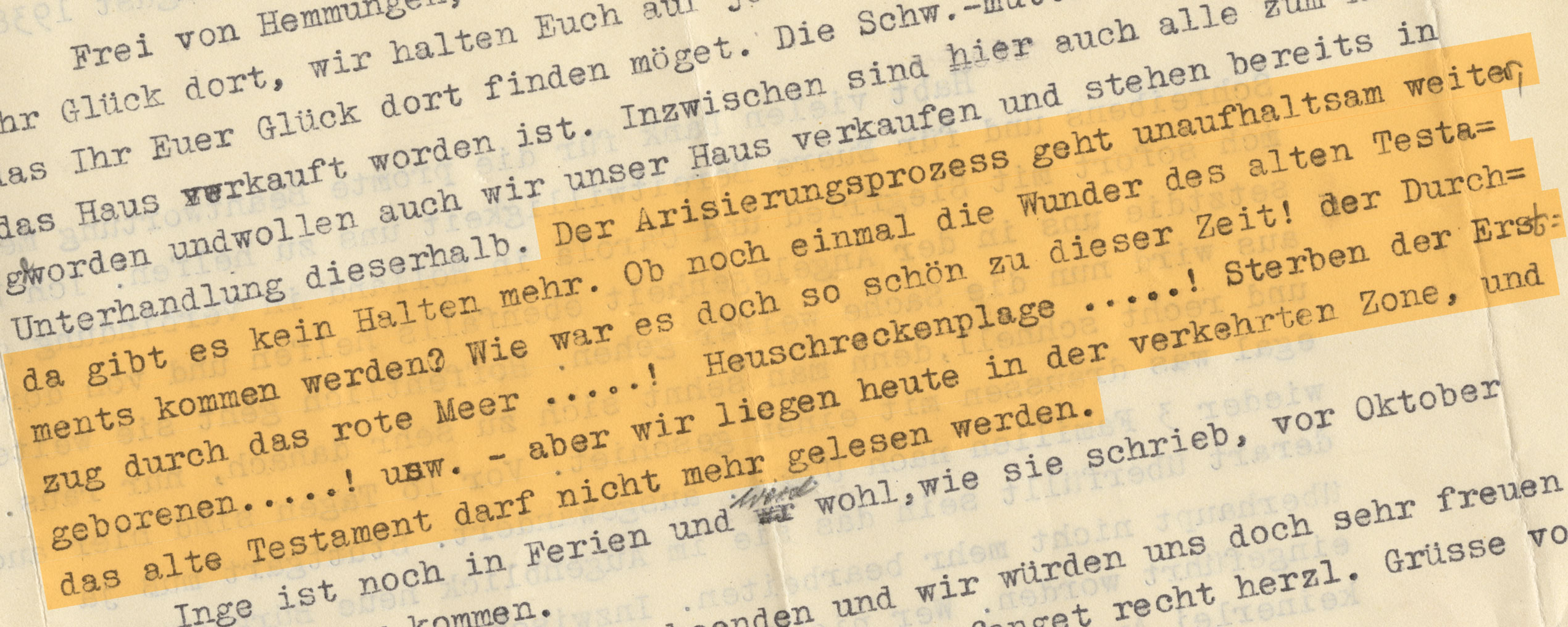

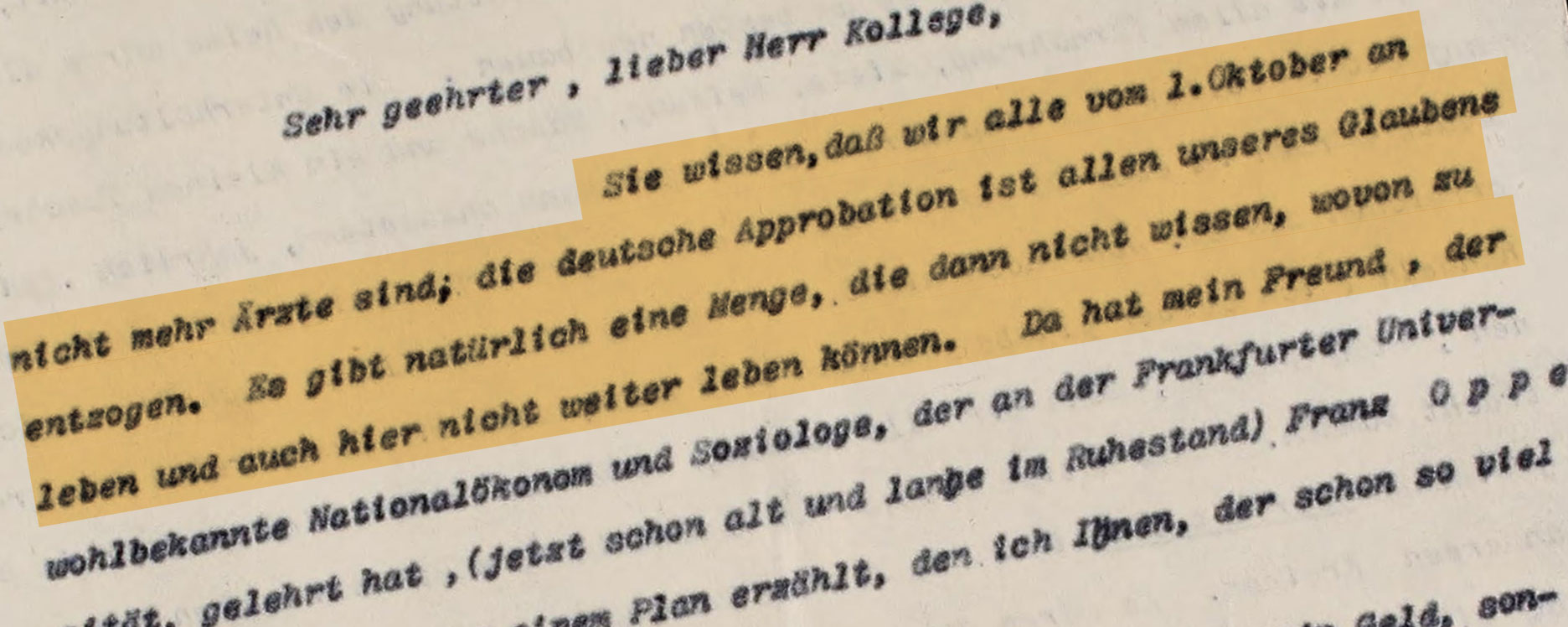

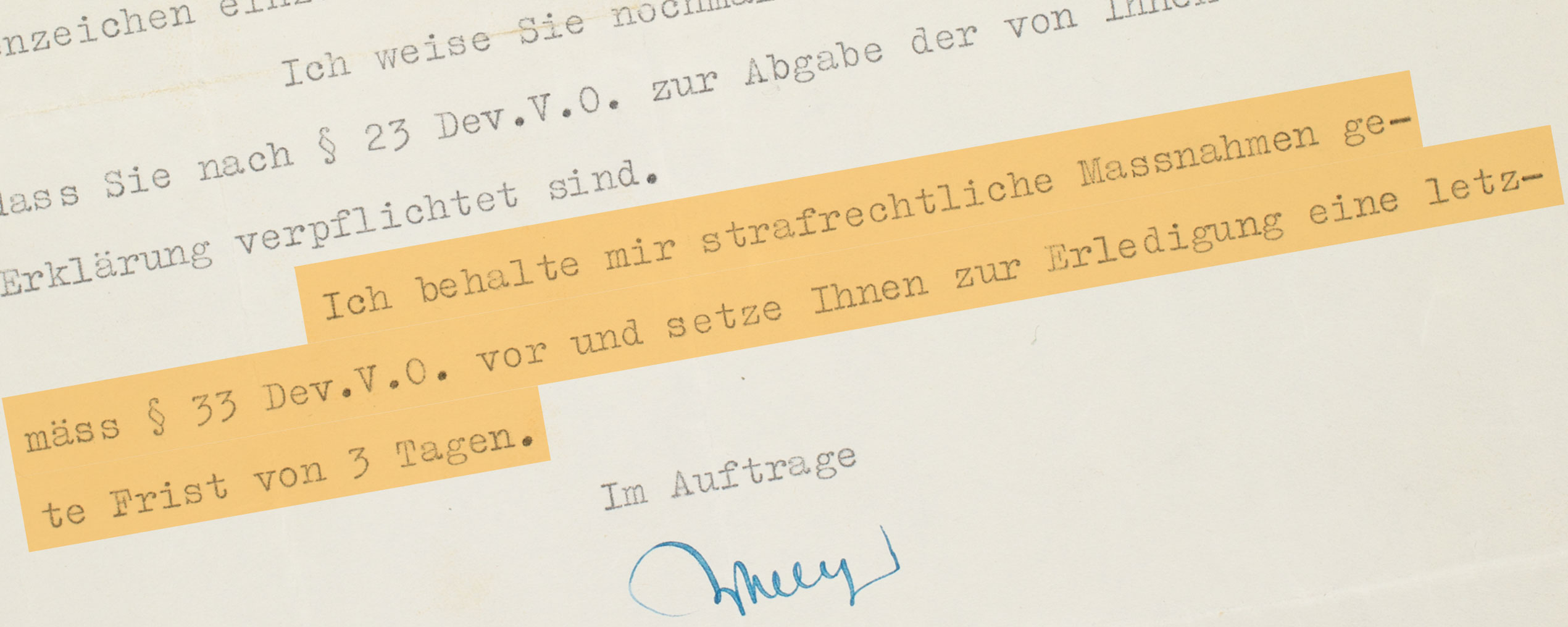

At the mercy of Nazi authorities

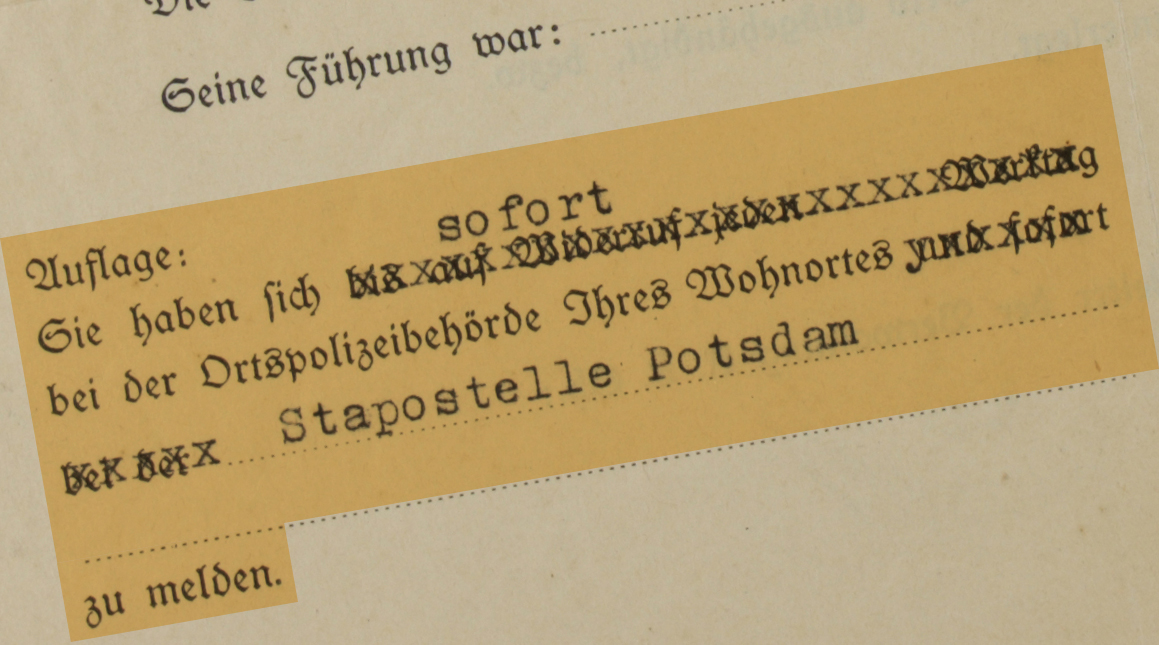

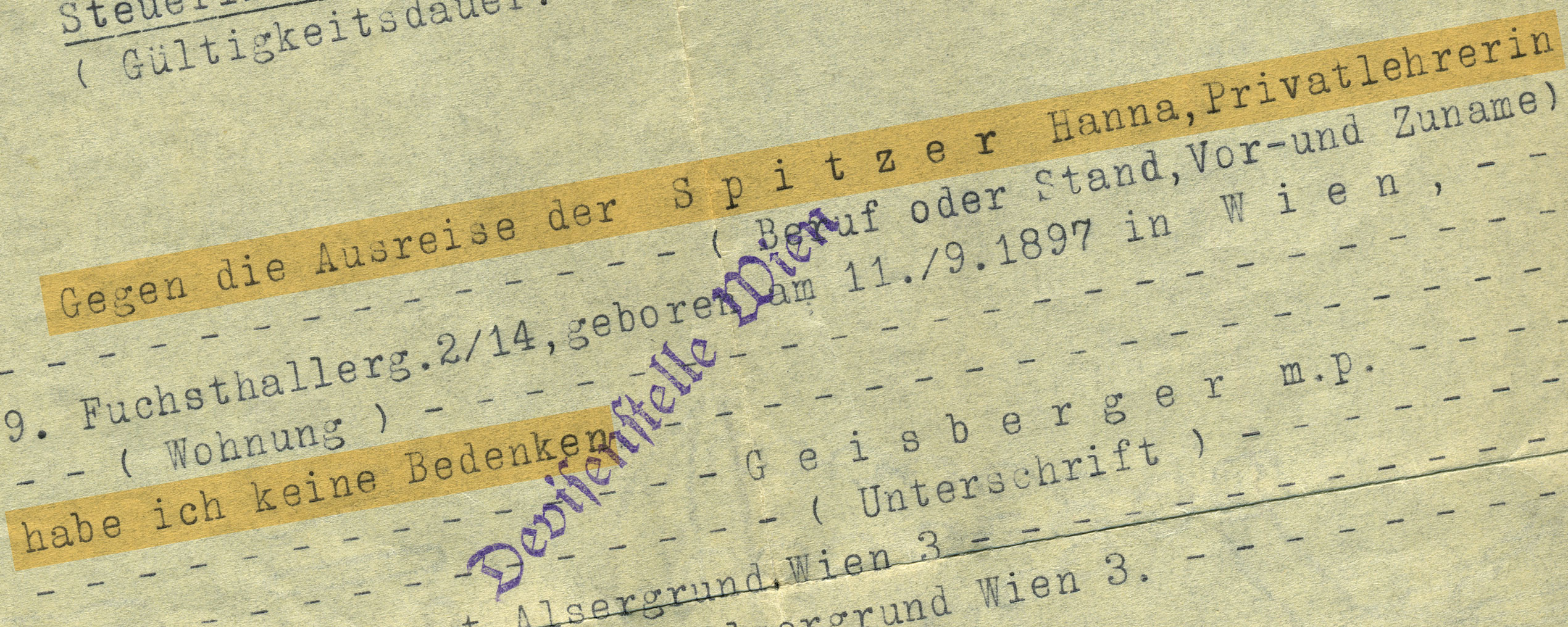

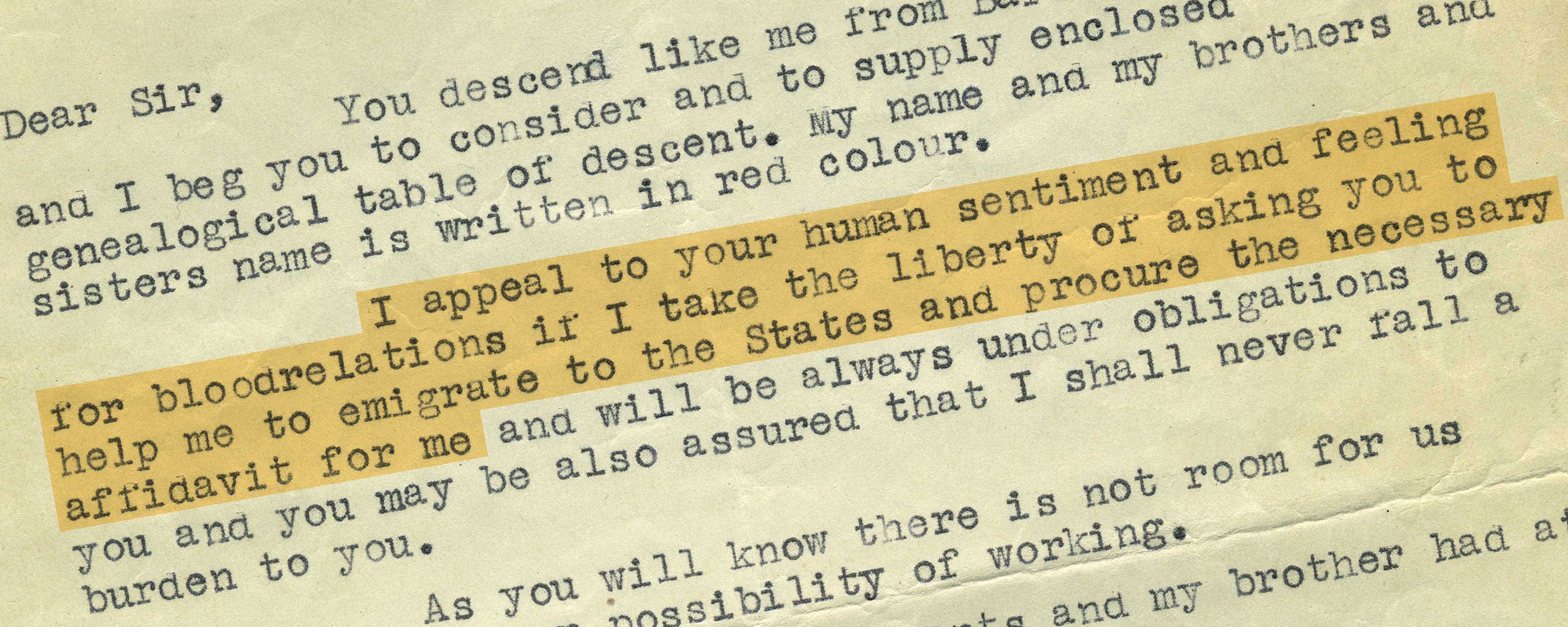

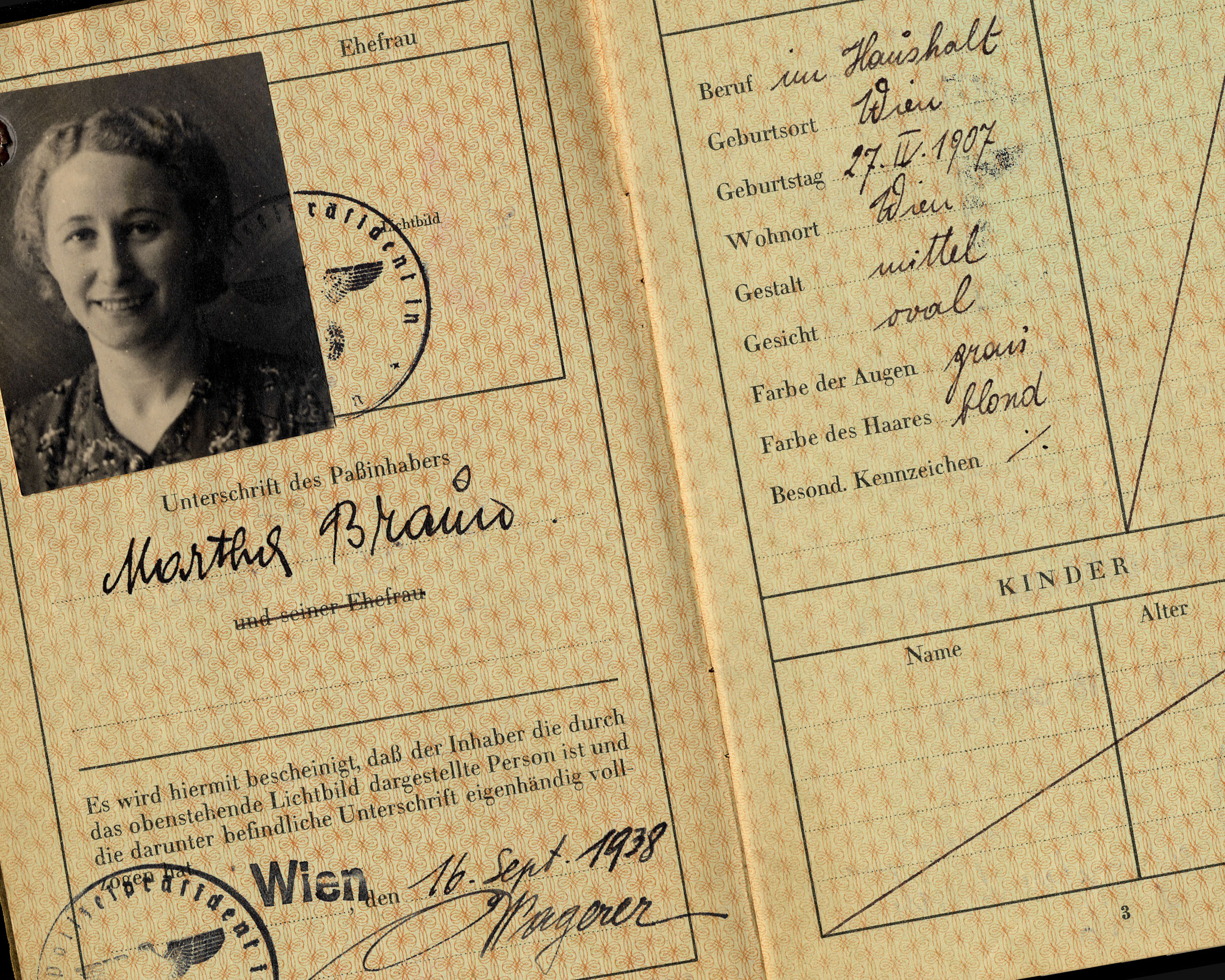

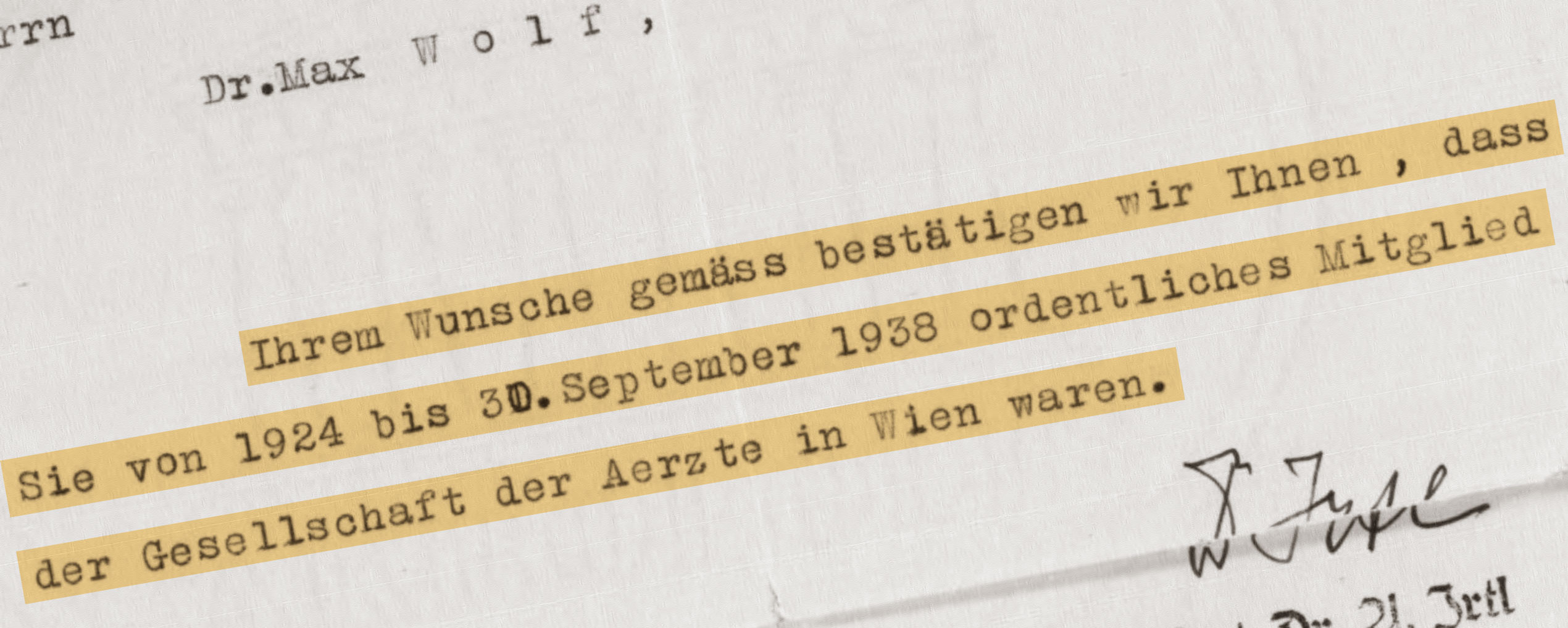

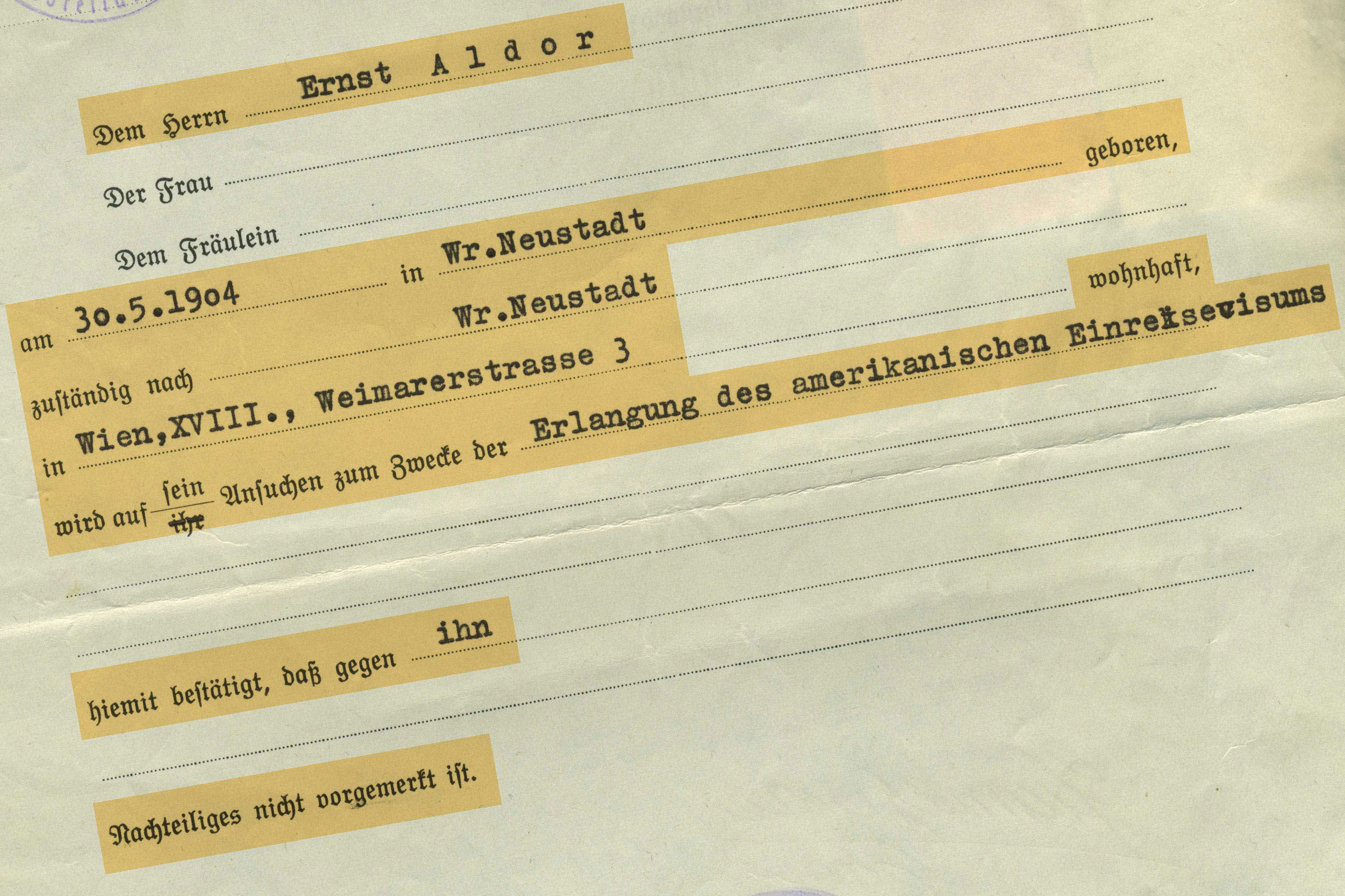

Bureaucratic requirements for emigration

“At the request of Mr. Ernst Aldor, born 05.30.1904 in Wr. Neustadt [a district of Vienna], right of residence in Wr. Neustadt in Vienna, resident at 3 Weimarer Street, it is hereby confirmed, for the purpose of obtaining his American immigration visa, that no adverse information is on record against him.”

Vienna

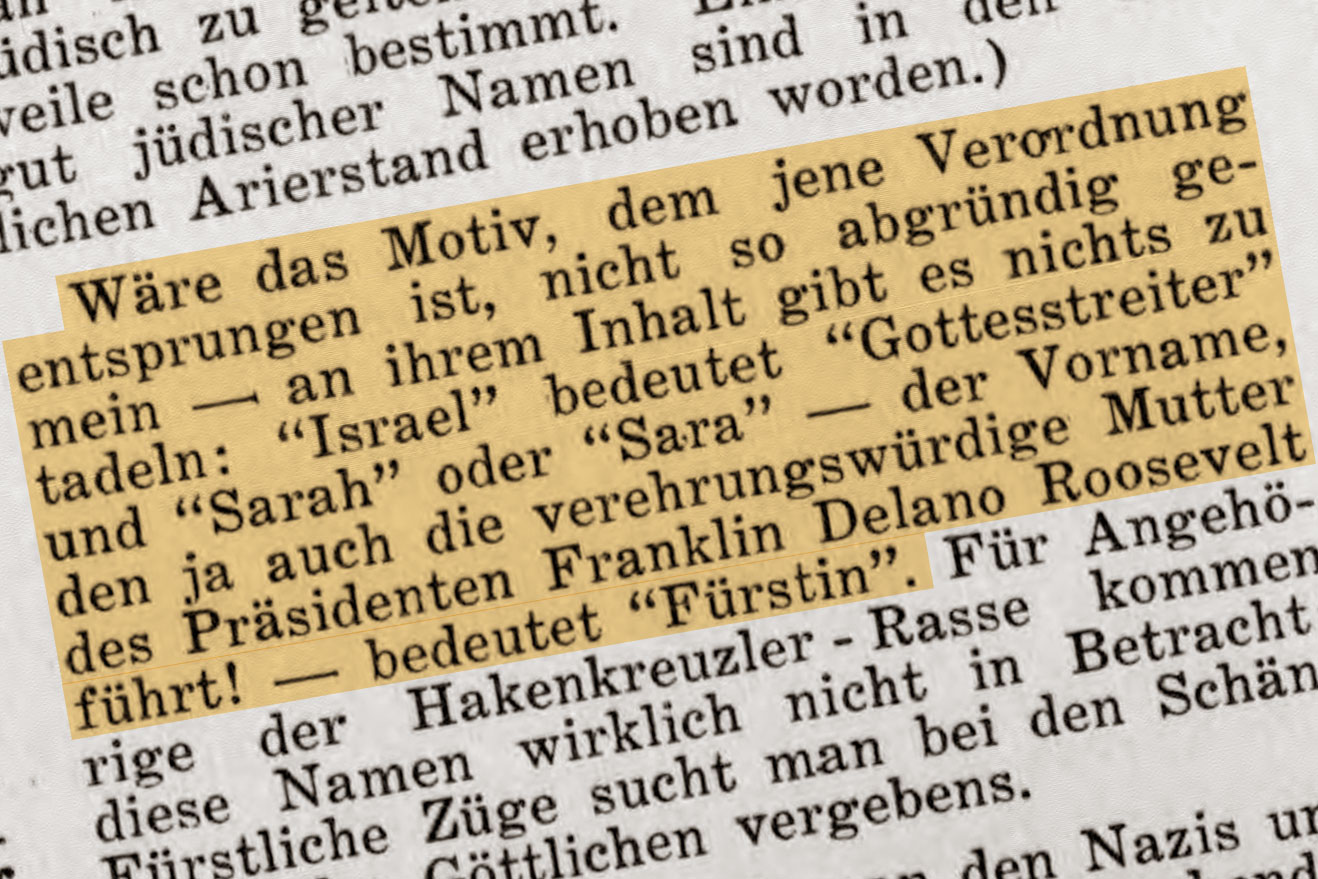

Not long after power was handed to the Nazis, the motto “Police – your friends and helpers,” which already during the Weimar Republic often reflected a hope rather than reality, lost any hint of meaning for opponents of the regime and for the country’s Jews. A law introduced as early as February 1933 stipulated that police officers who resorted to the use of firearms against people perceived as enemies of the regime were to go unpunished. As part of an unholy trinity, in tandem with the SA and SS, the police quickly became an instrument of Nazi terror. Therefore, obtaining a police clearance certificate was probably not the easiest of the requirements of would-be immigrants applying for US visas. On December 24th, 1938, this important document was issued to Ernst Aldor, a resident of Vienna.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Renee Aldor Collection, AR 10986

Original:

Box 1, folder 3

Source available in English