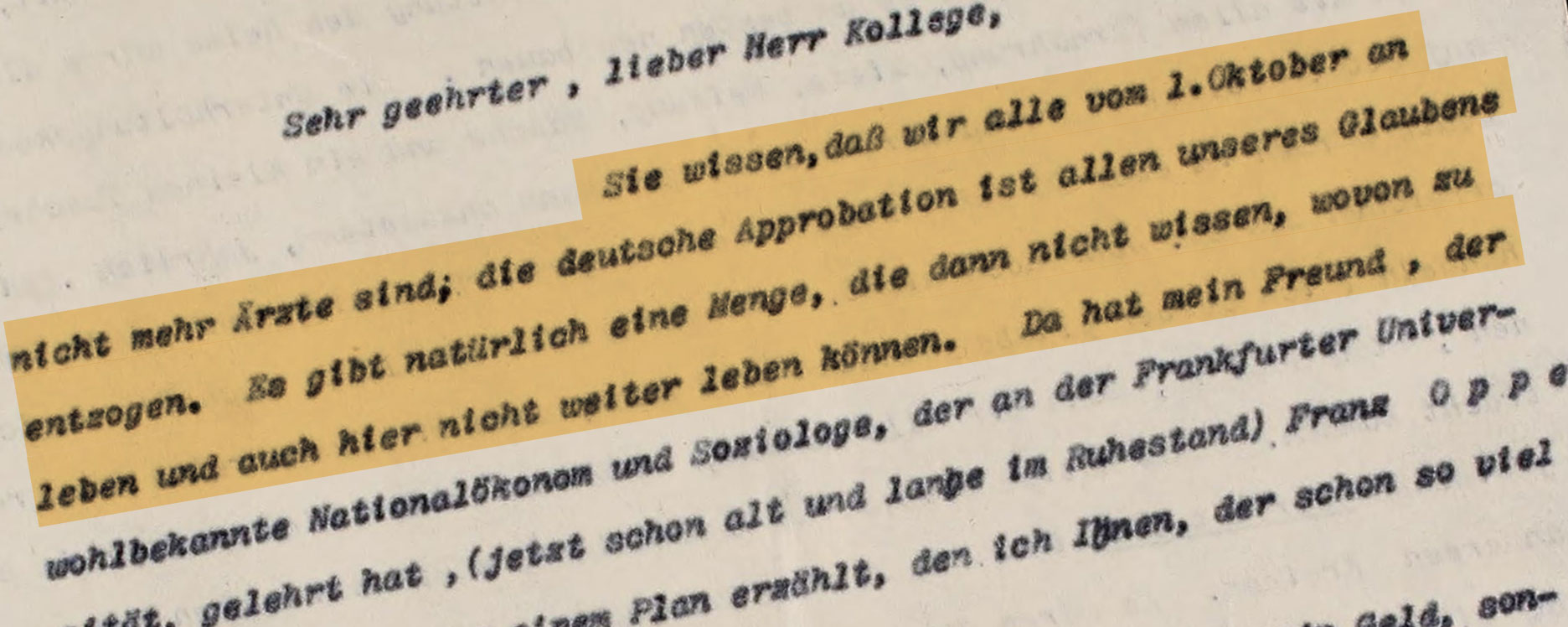

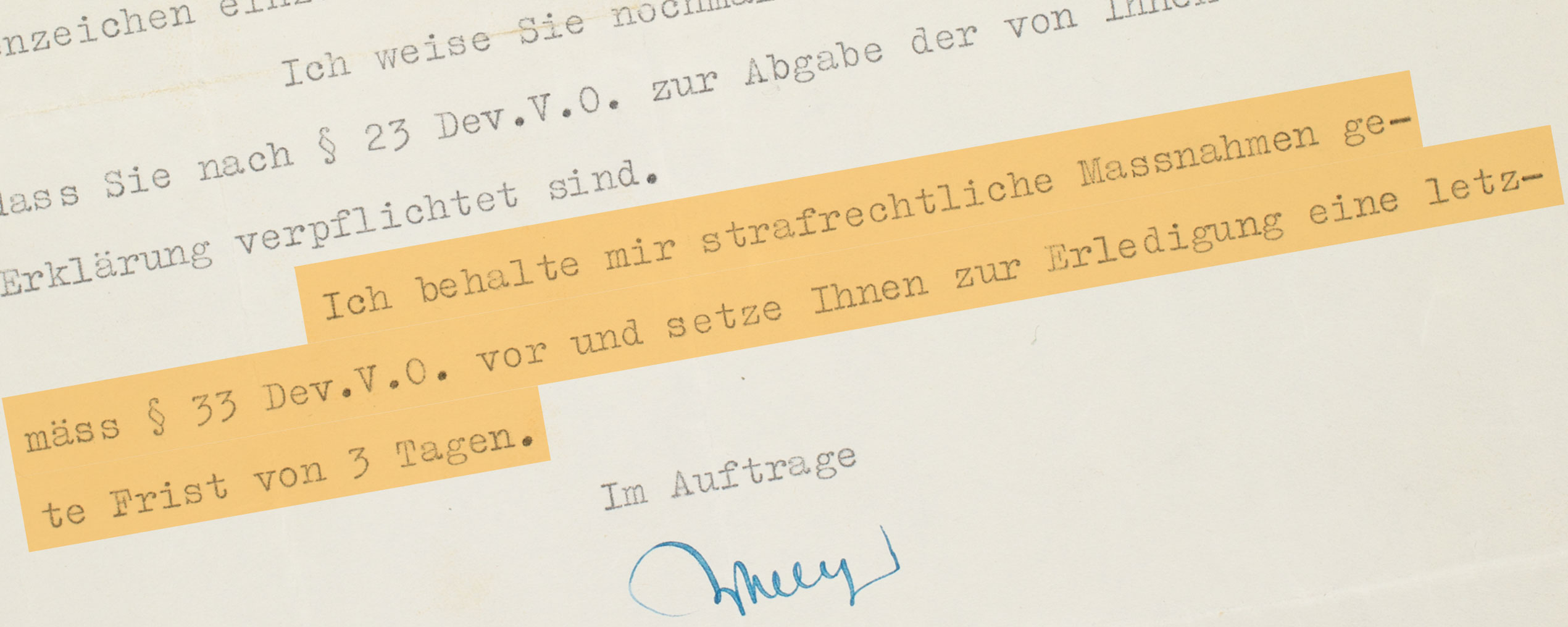

Fake generosity

Forced emigration from Burgenland

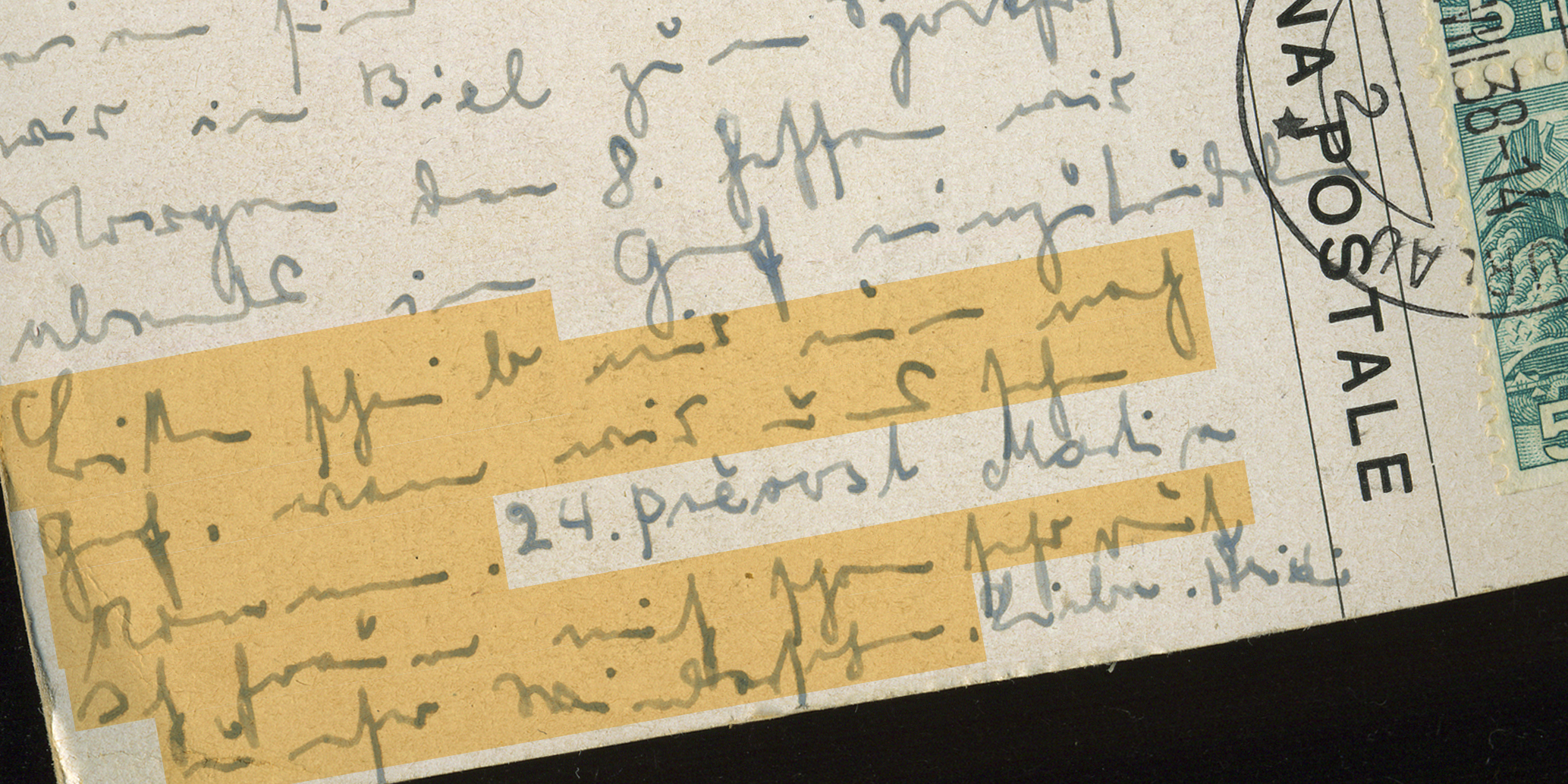

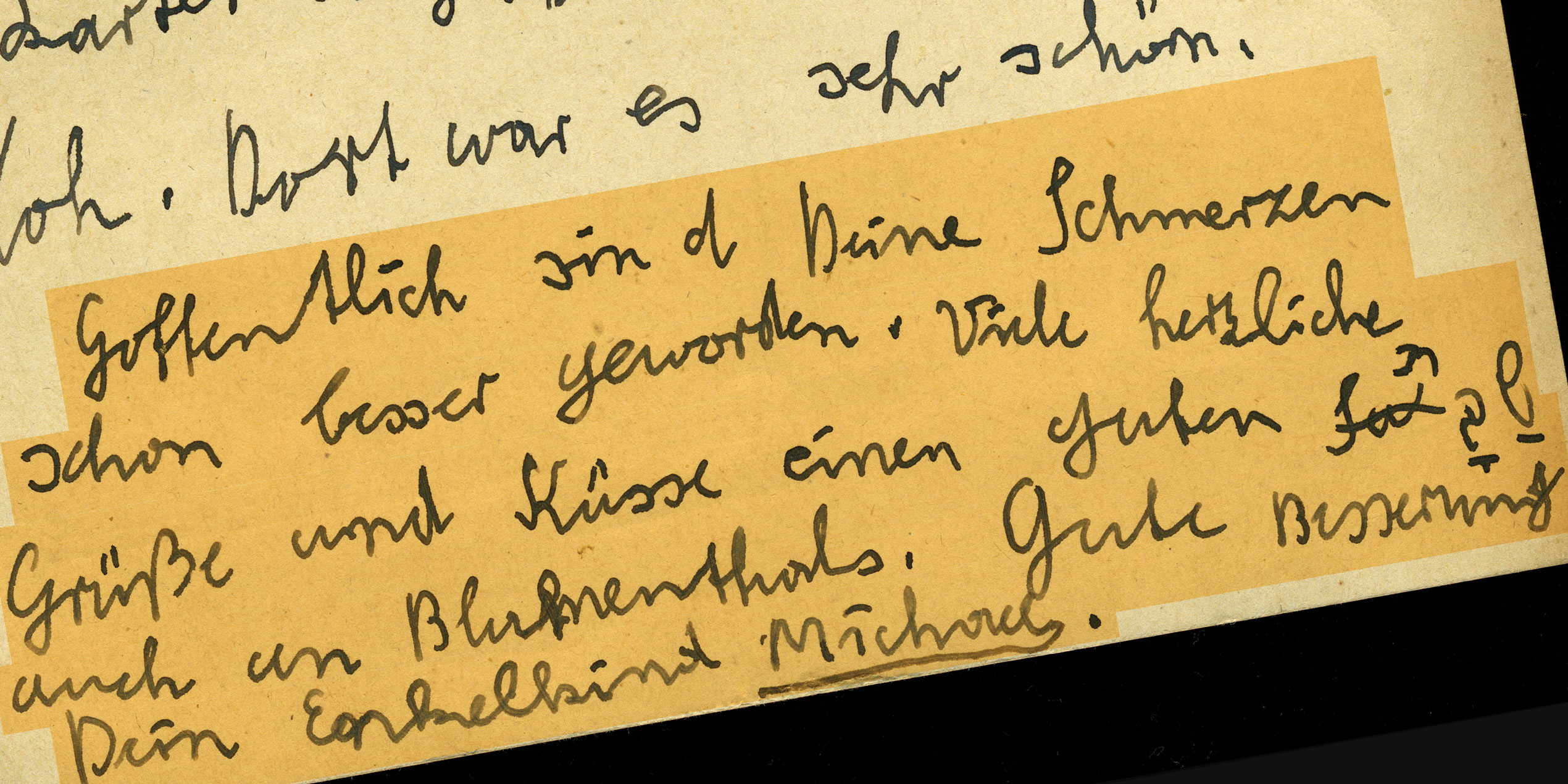

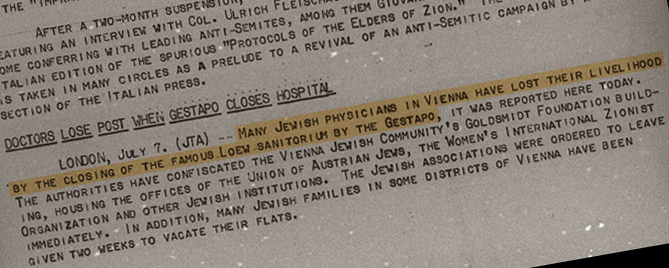

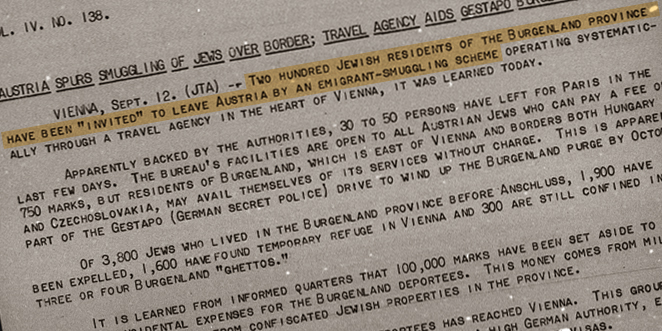

“Two hundred Jewish residents of Burgenland province were ‘invited’ to leave Austria by an emigrant-smuggling scheme.”

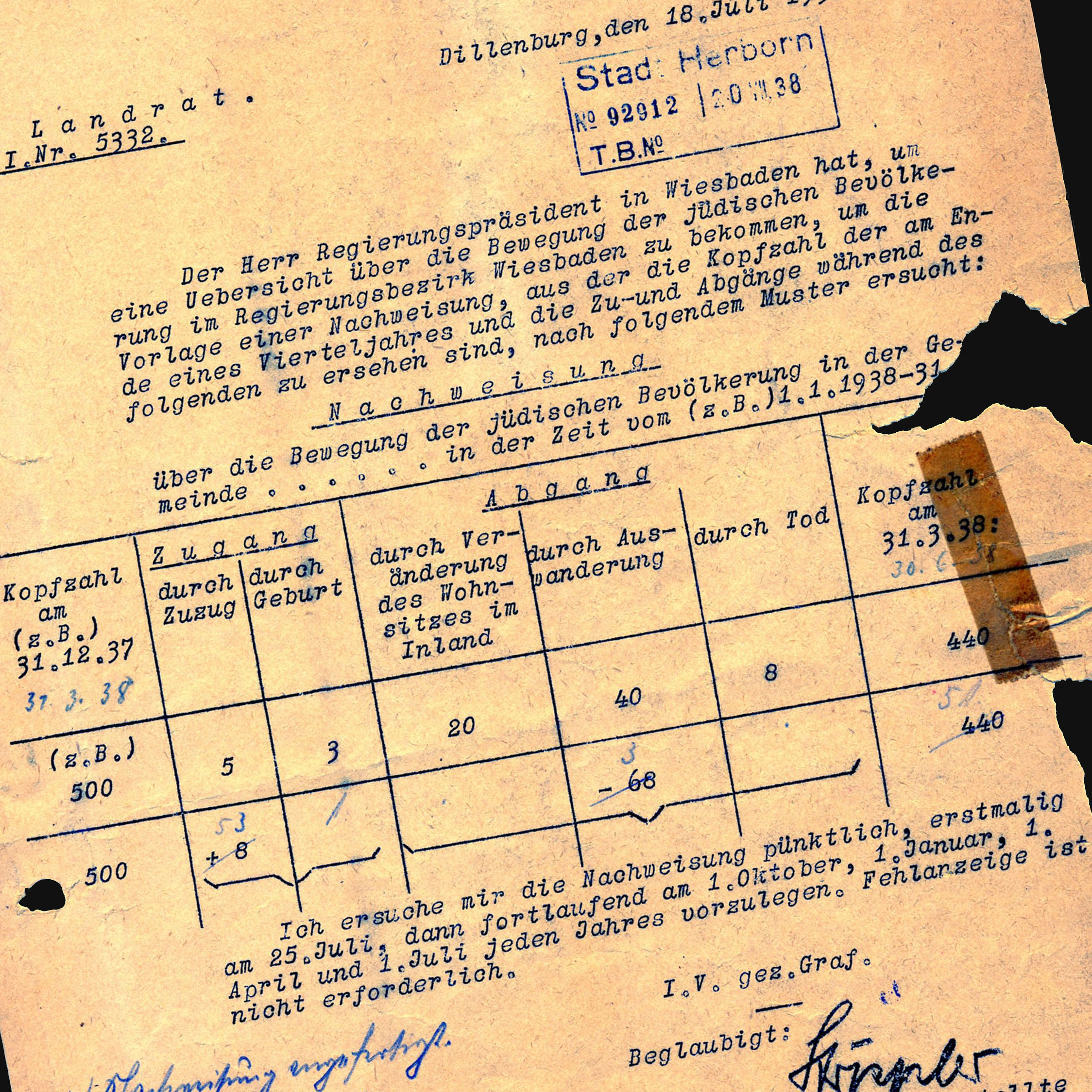

Eisenstadt, Burgenland

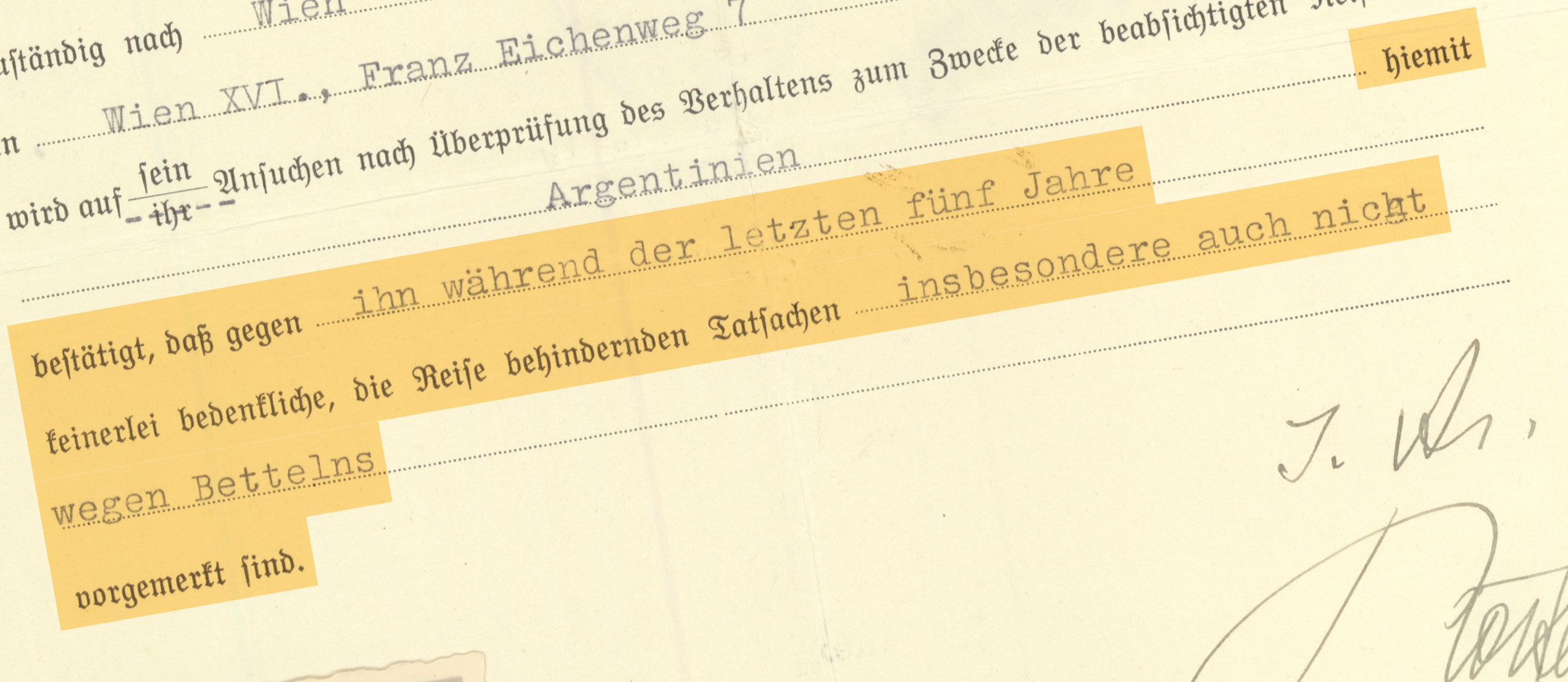

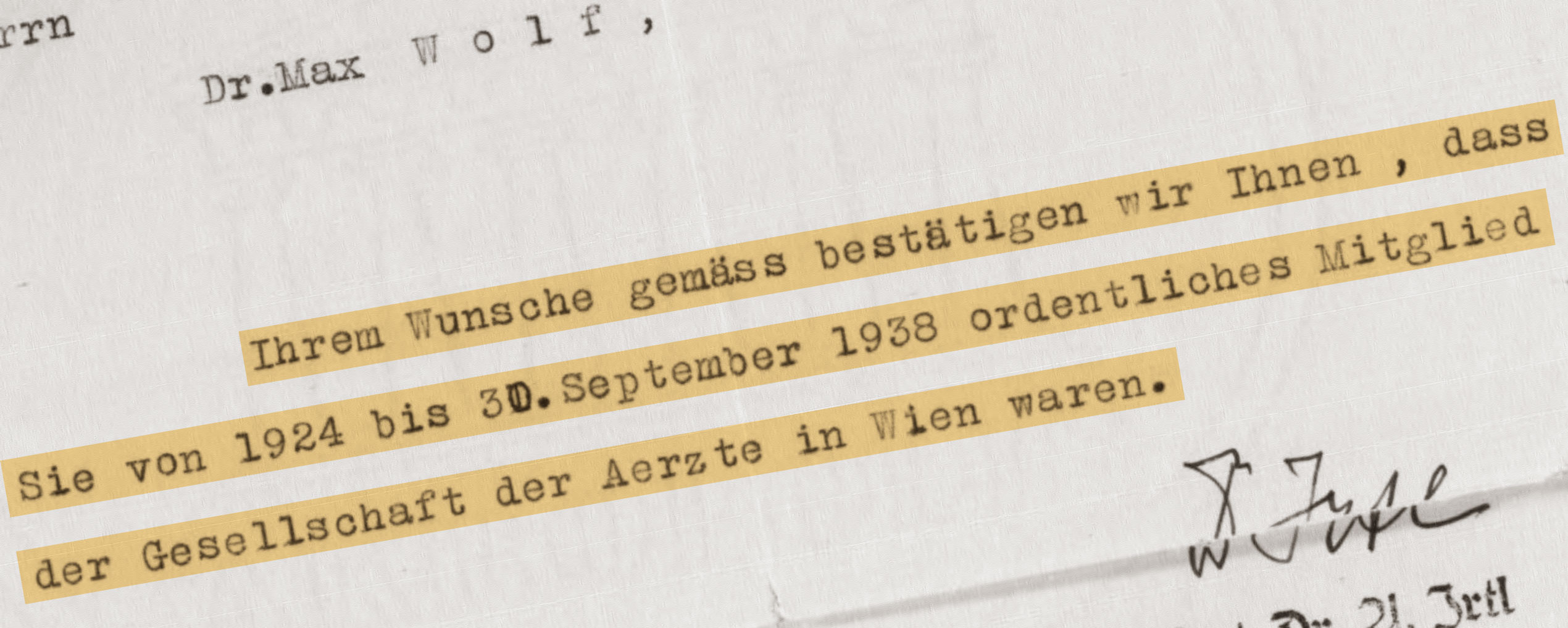

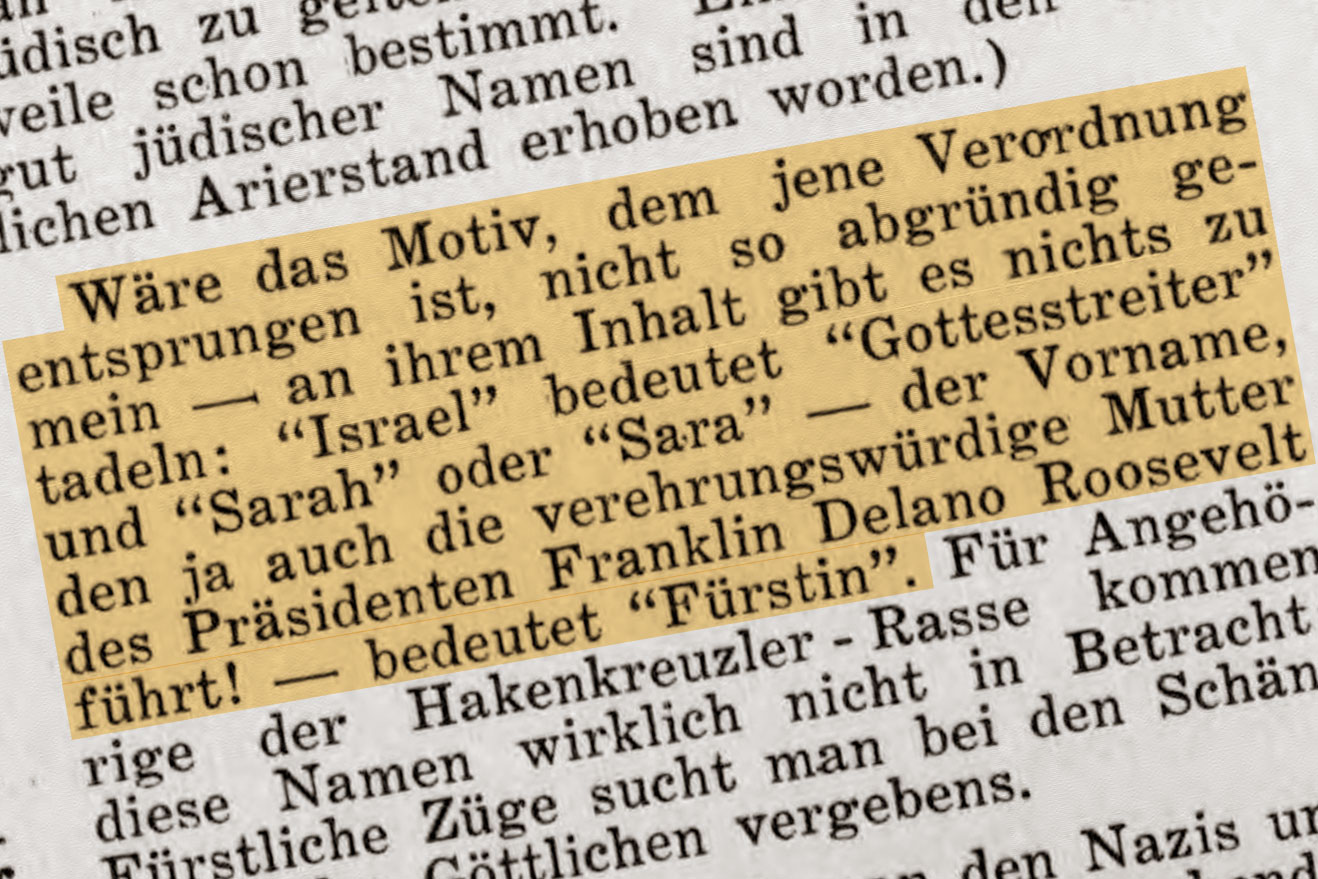

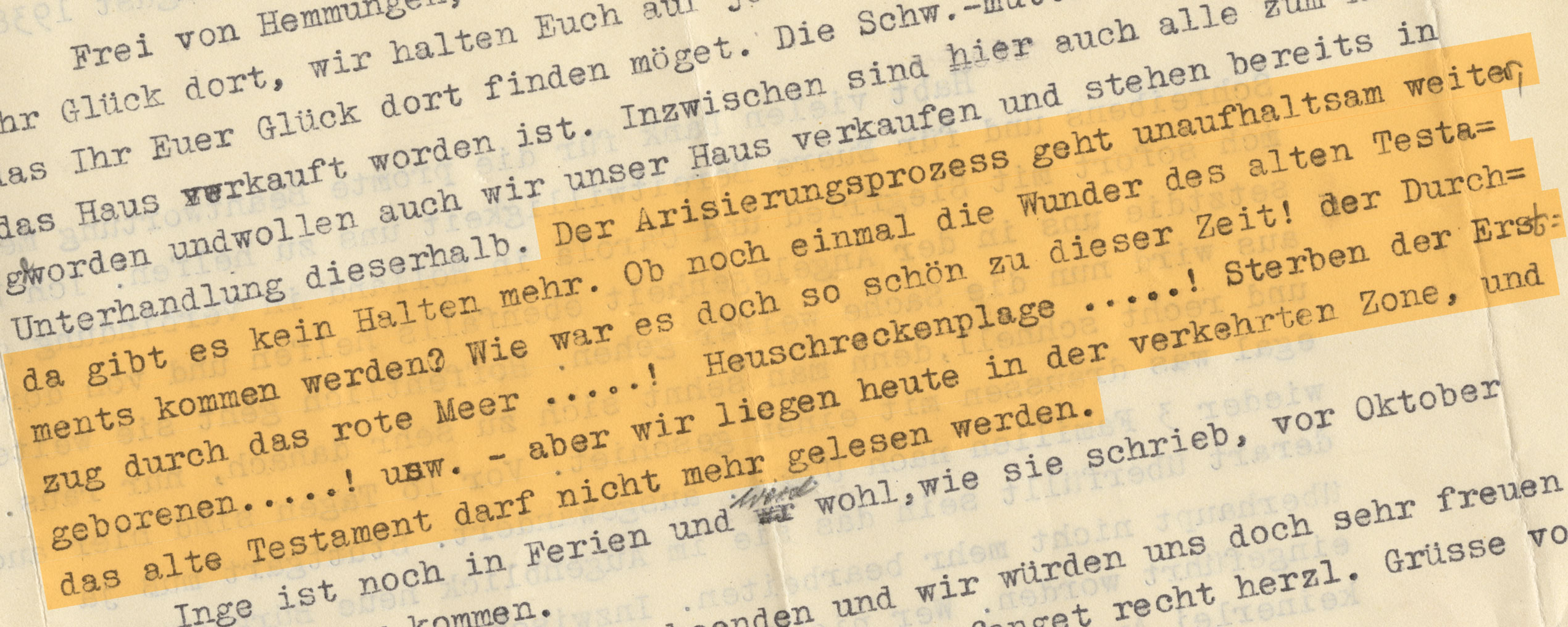

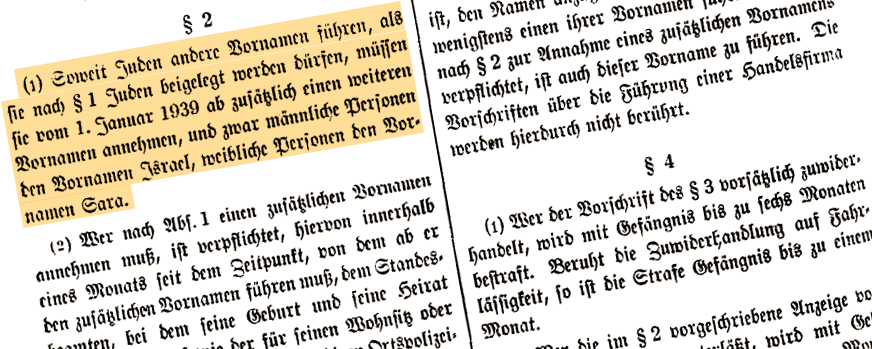

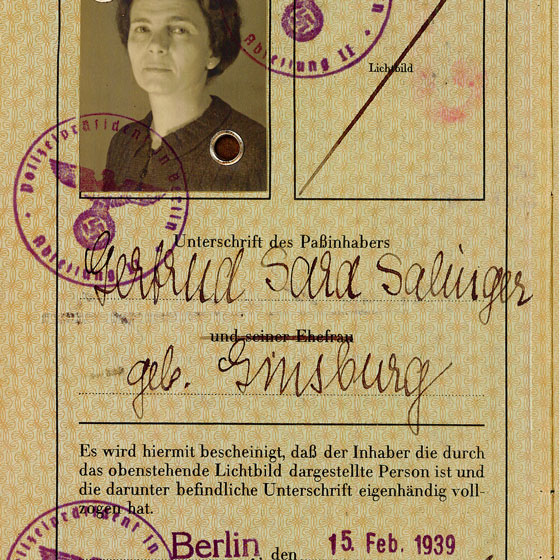

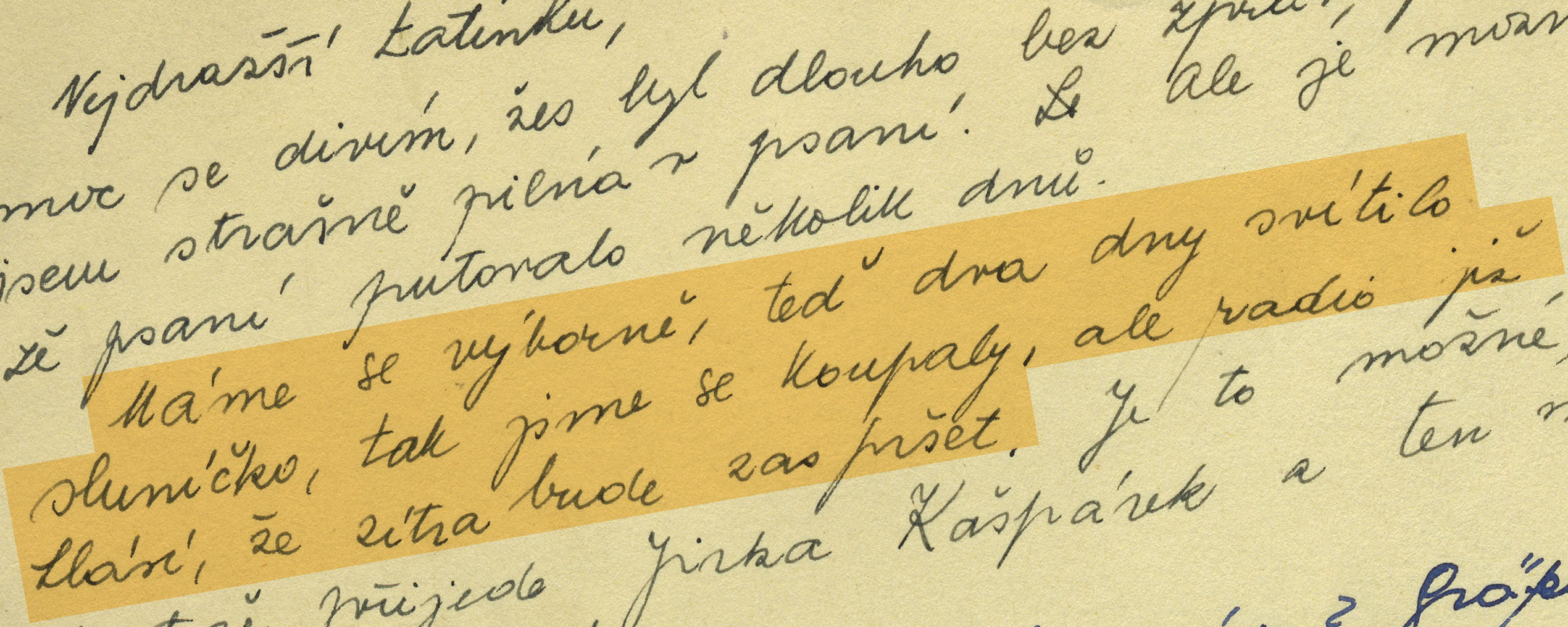

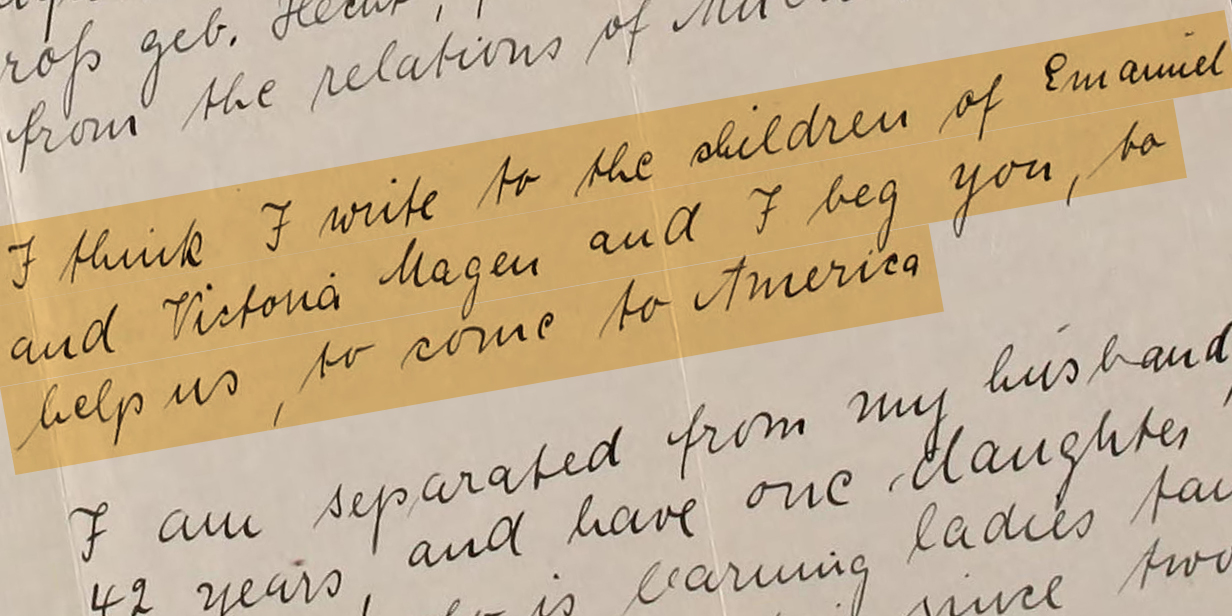

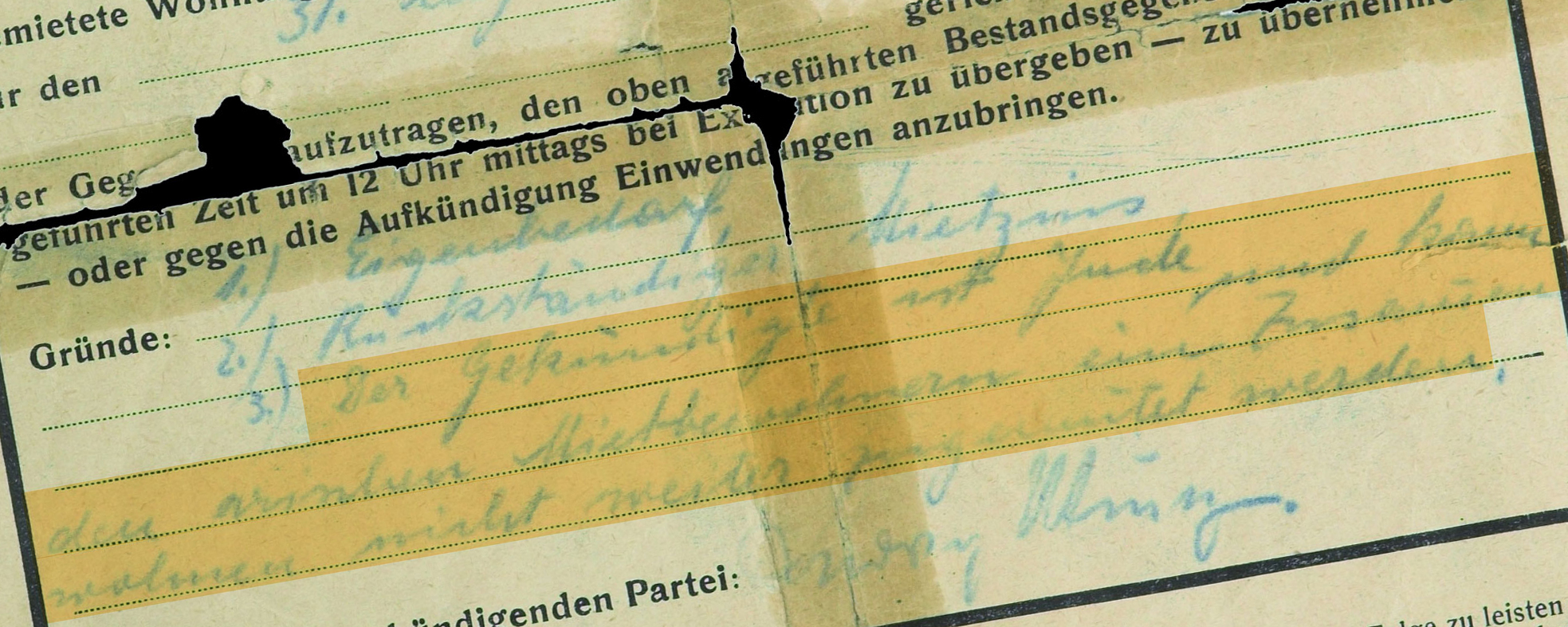

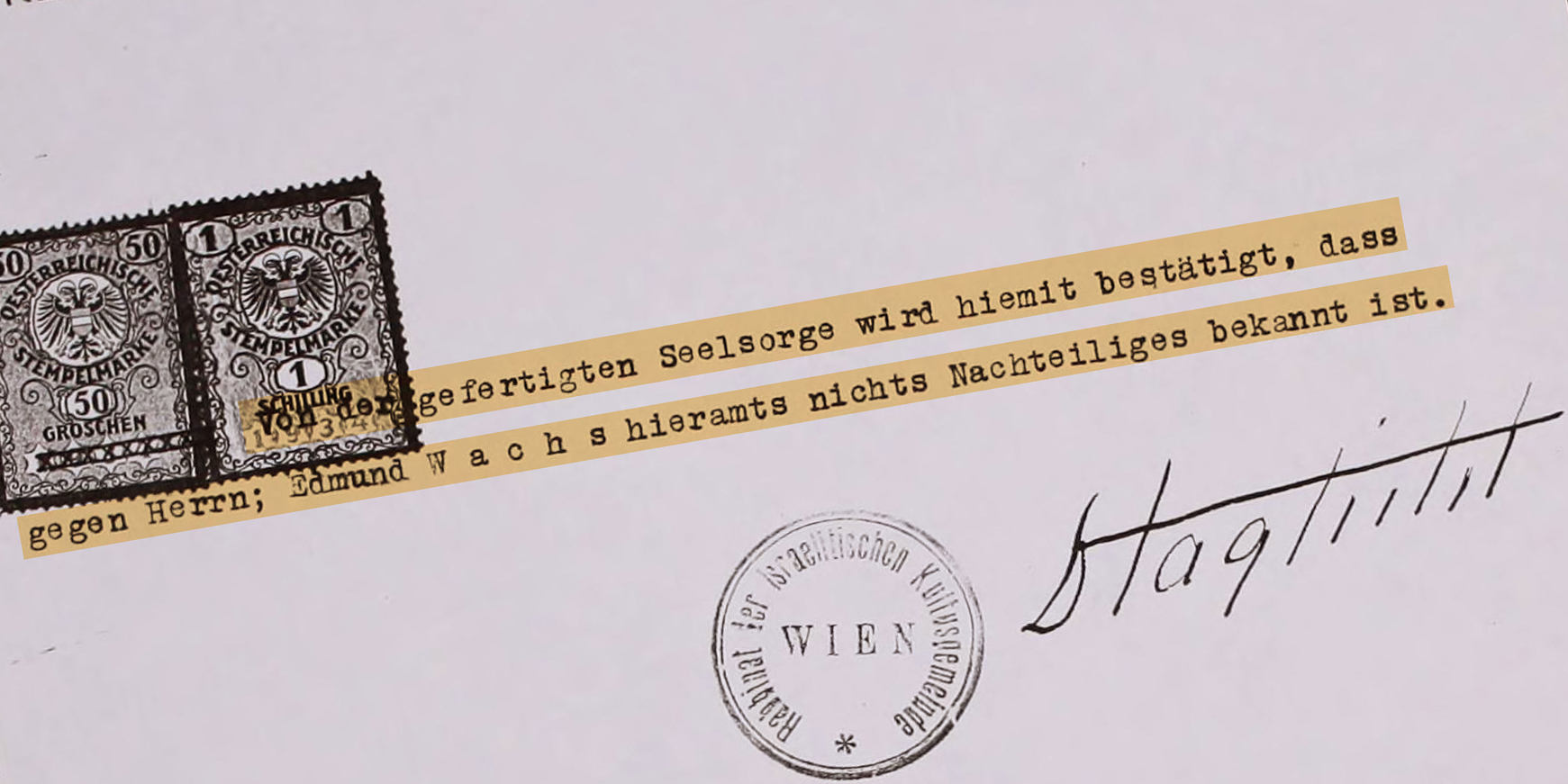

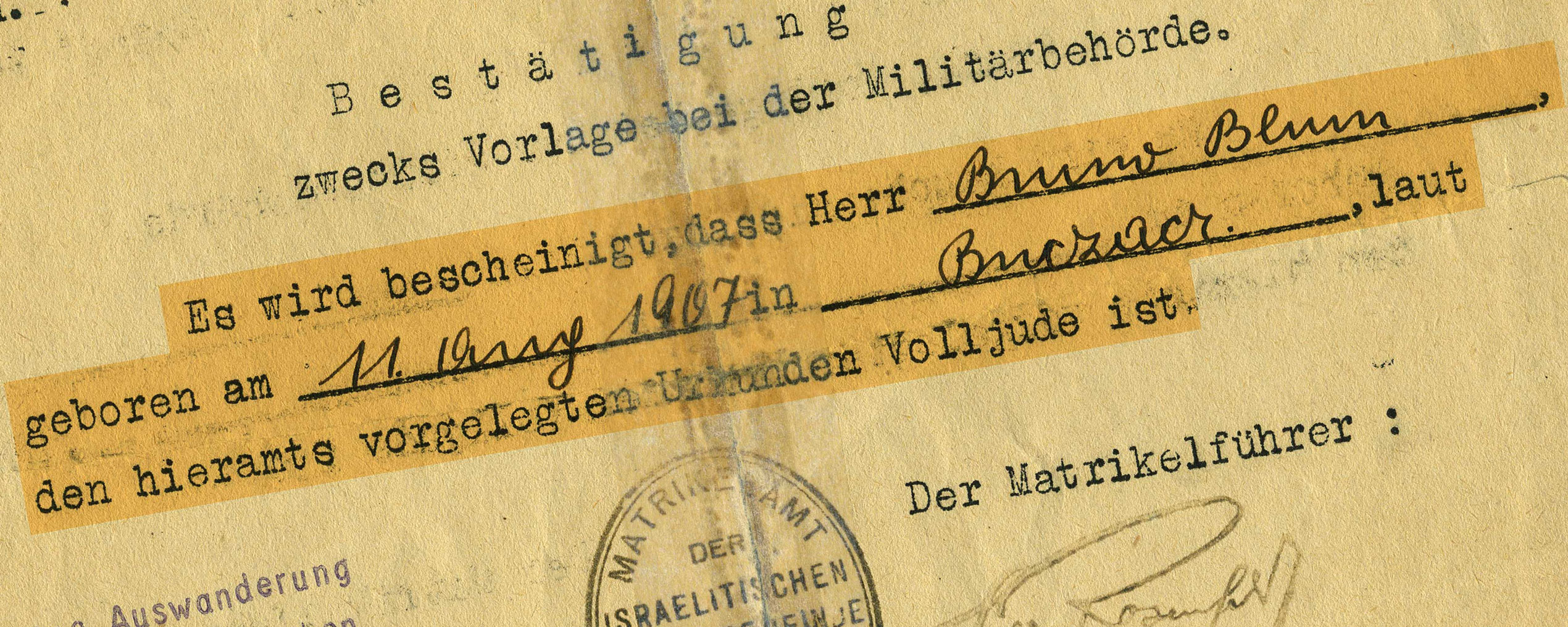

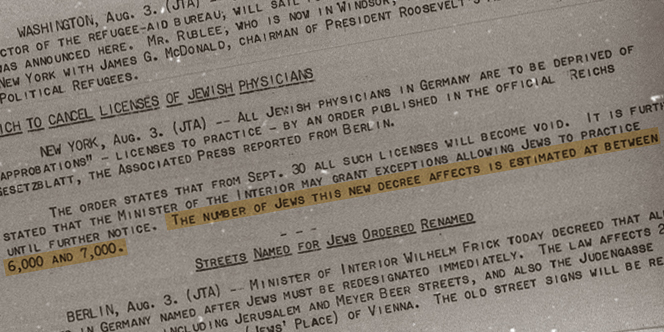

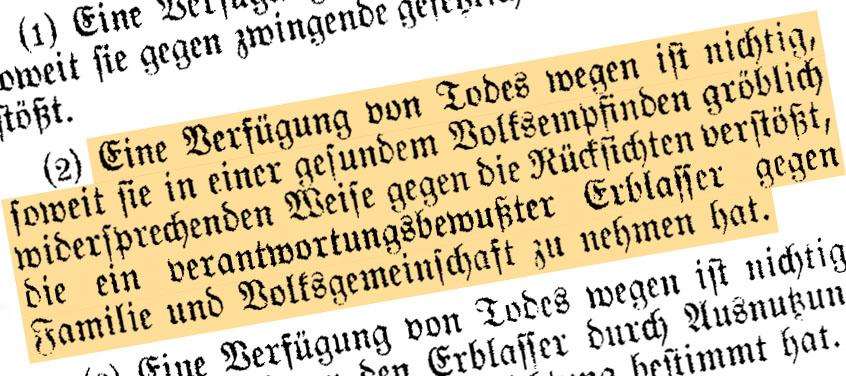

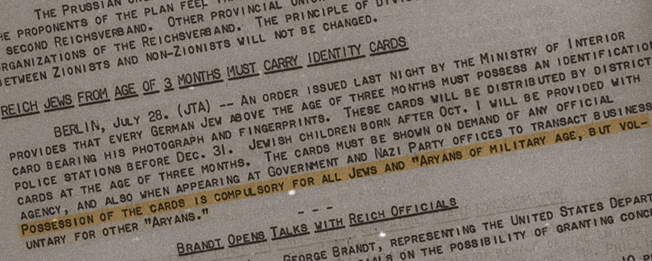

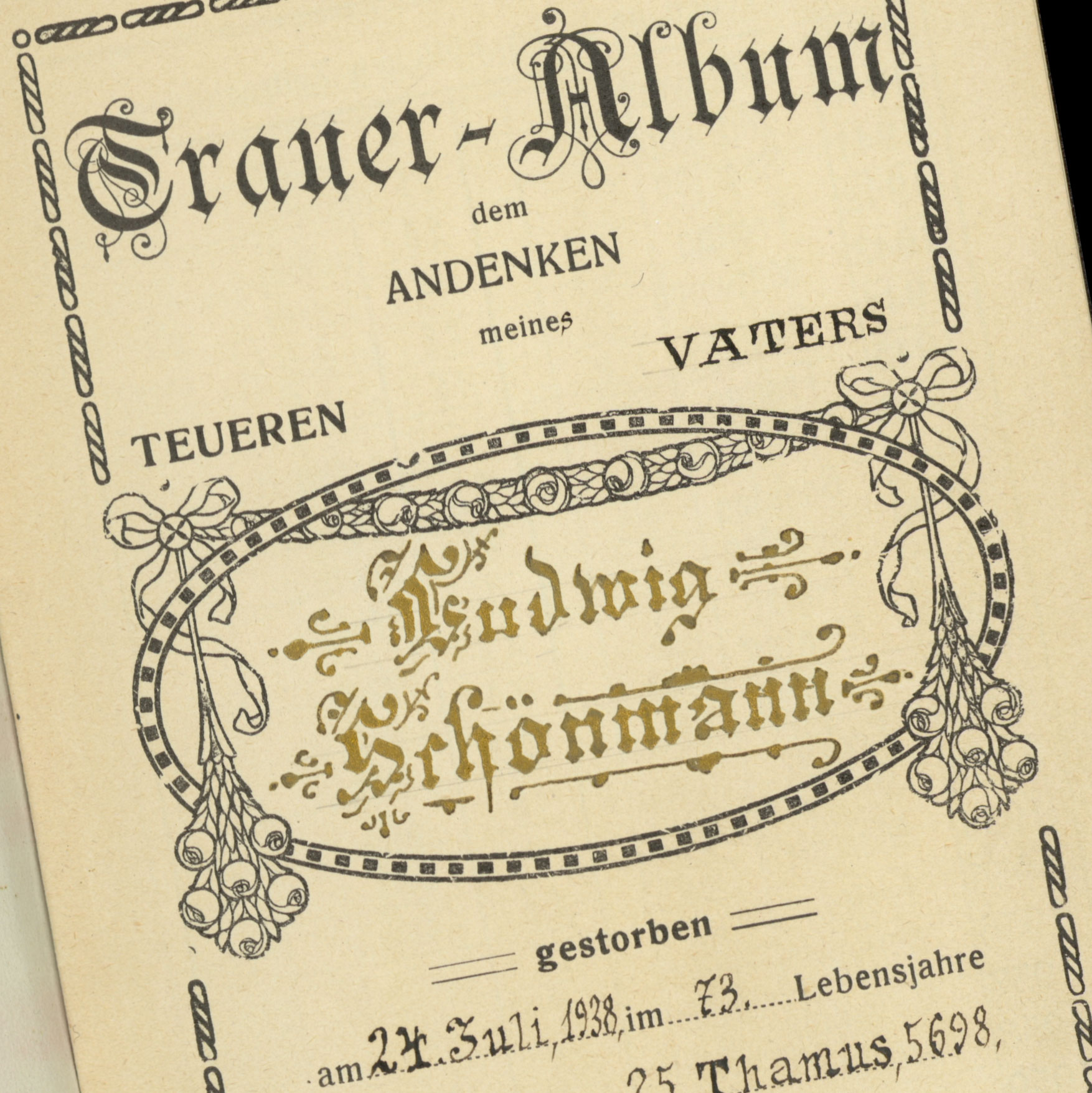

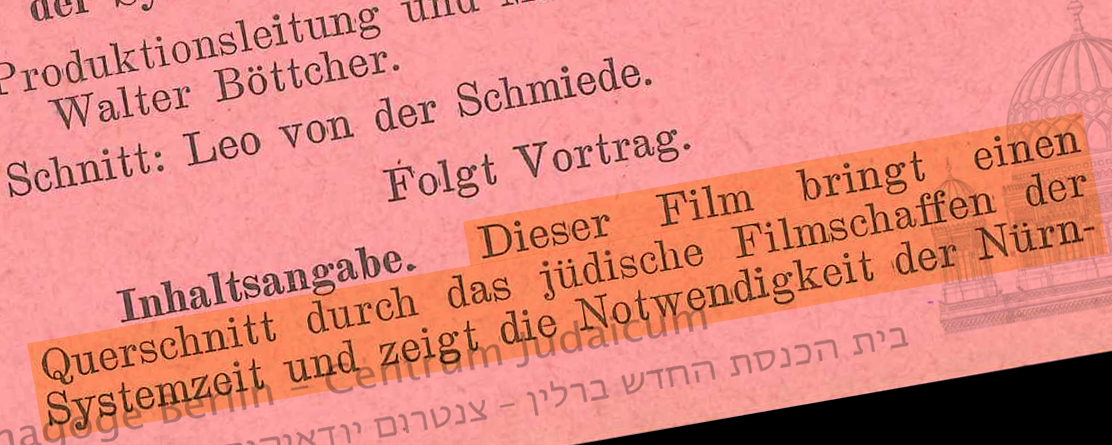

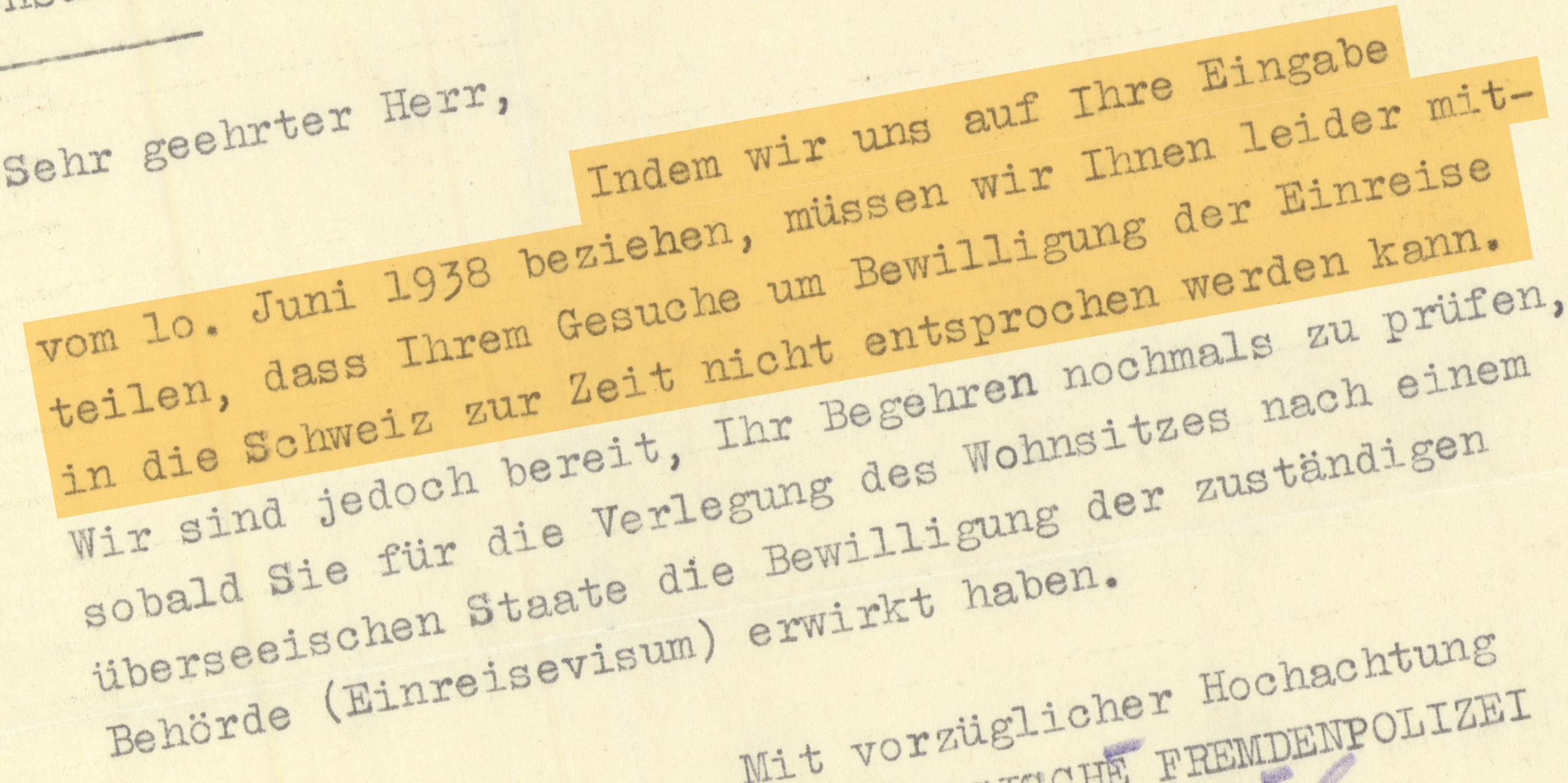

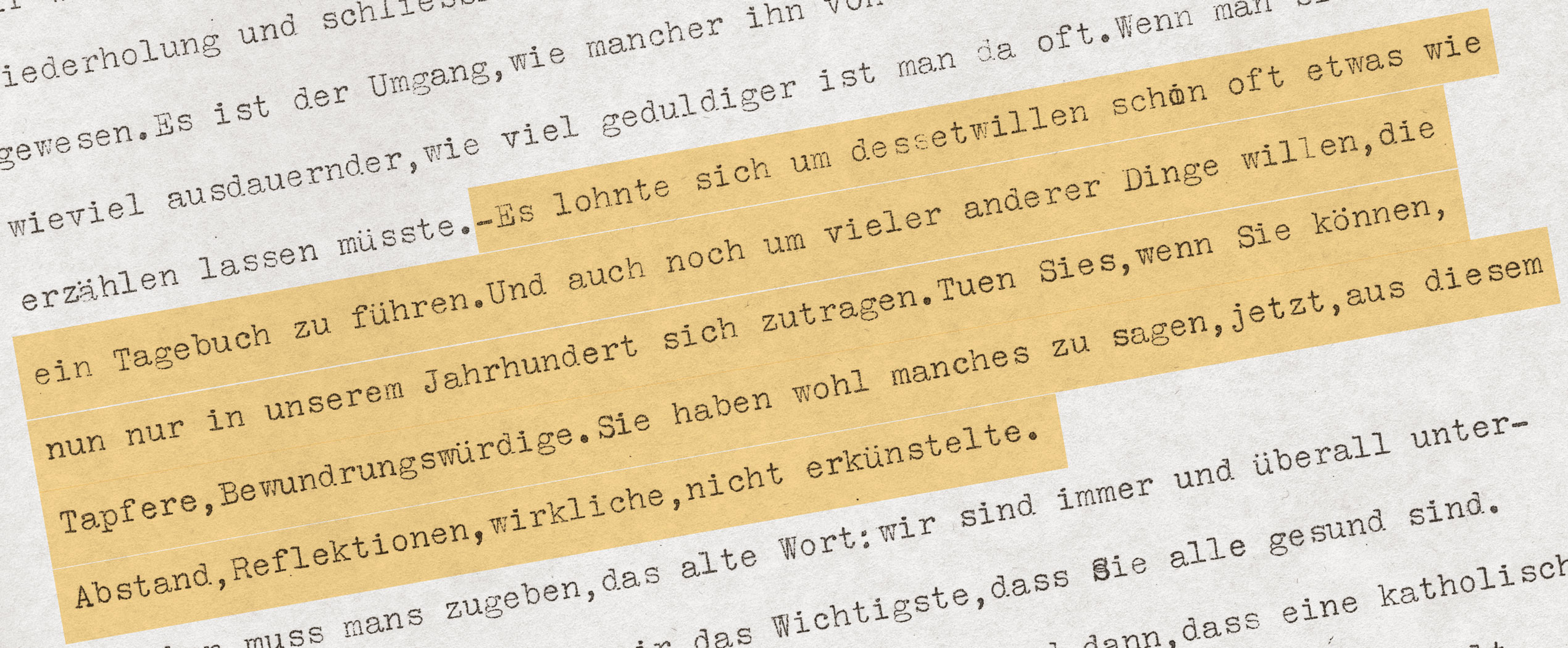

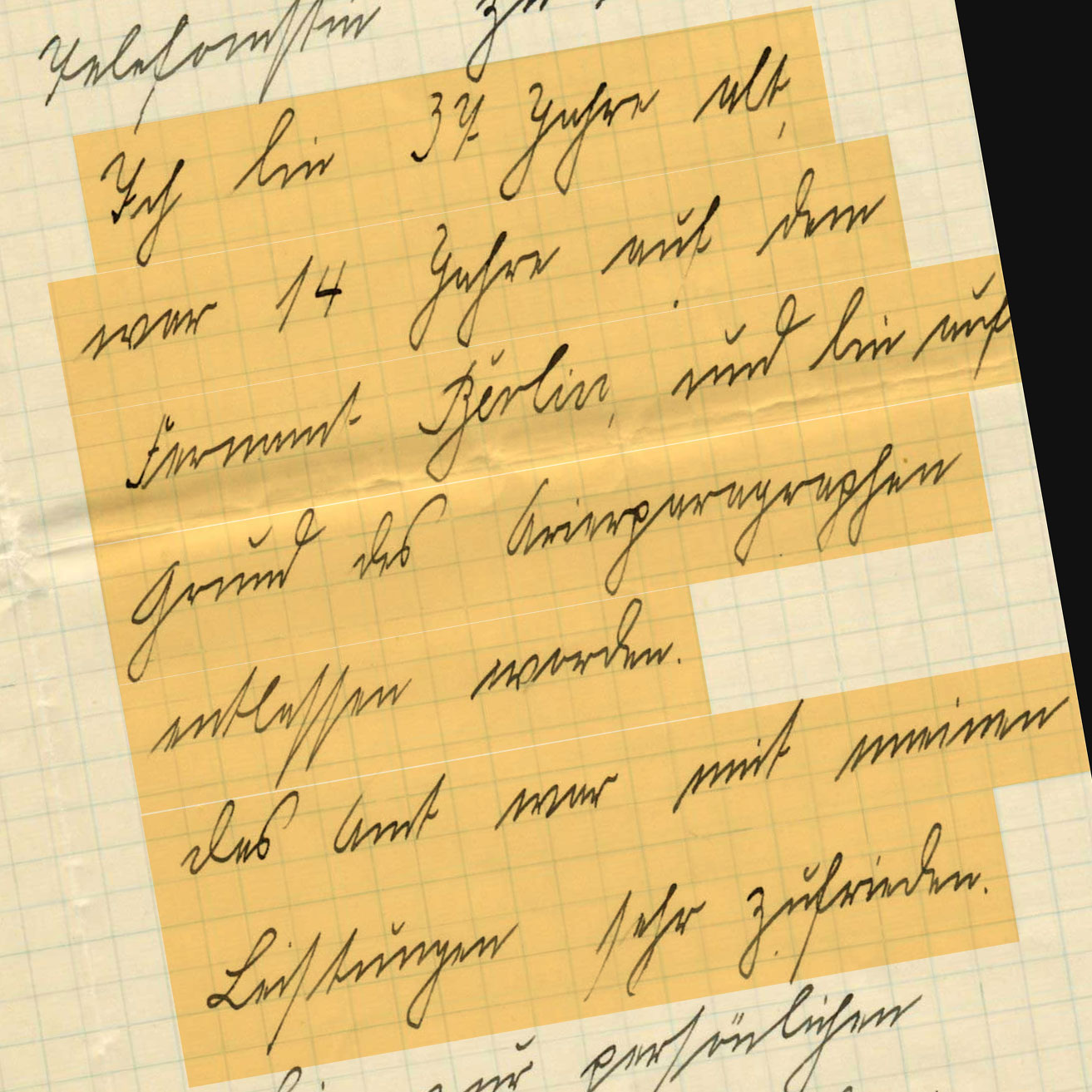

“Free-of-charge”: it may seem like a generous “offer,” but behind this “free-of-charge” offer was ice-cold calculation. The Nazis’ evil intent was that all Jews still remaining in Burgenland, Austria, should leave the region. In Nazi jargon, this was called cleansing. After the “Anschluss,” Burgenland was the first Austrian region in which they had begun to systematically dispossess and expel the Jewish population. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported on September 12th that out of the 3,800 Jews, who had previously lived in Burgenland, 1,900 had already been expelled, 1,600 people had fled temporarily to Vienna, and another 300 were interned in ghettos in Burgenland. According to JTA, the “offer” of the emigrant-smuggling group was financed by the Gestapo with 100,000 marks from the assets of the recently dispossessed Jews of the region.

SOURCE

Institution:

Collection:

“Austria Spurs Smuggling of Jews over Border; Travel Agency Aids Gestapo Burgenland Purge”

Source available in English