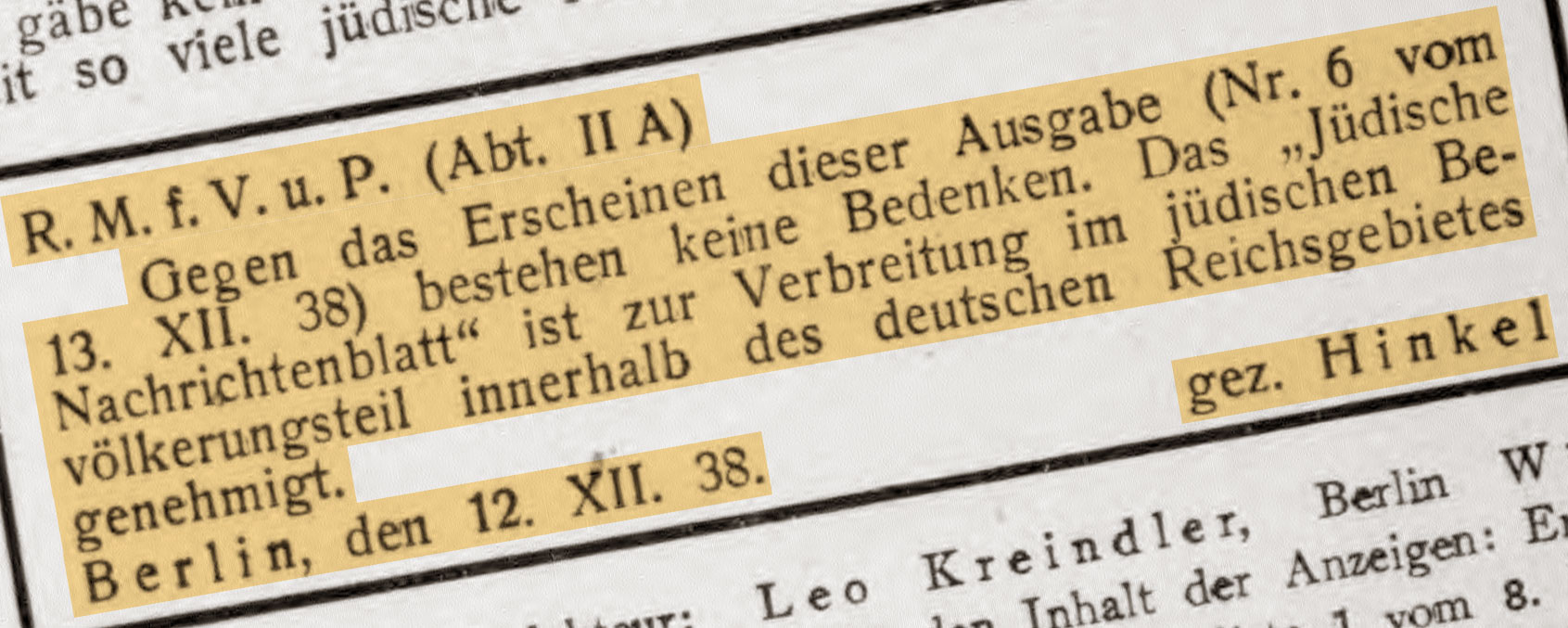

A totalitarian regime fears the free press

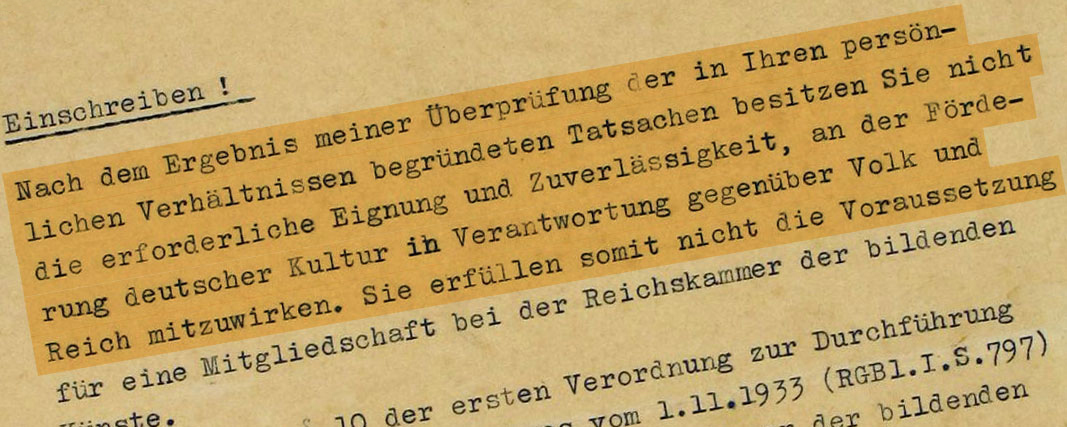

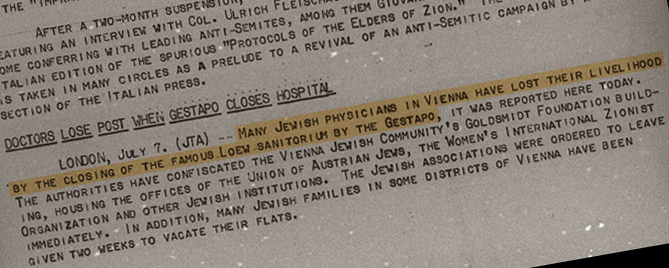

Victims of Nazi employment bans meet in exile

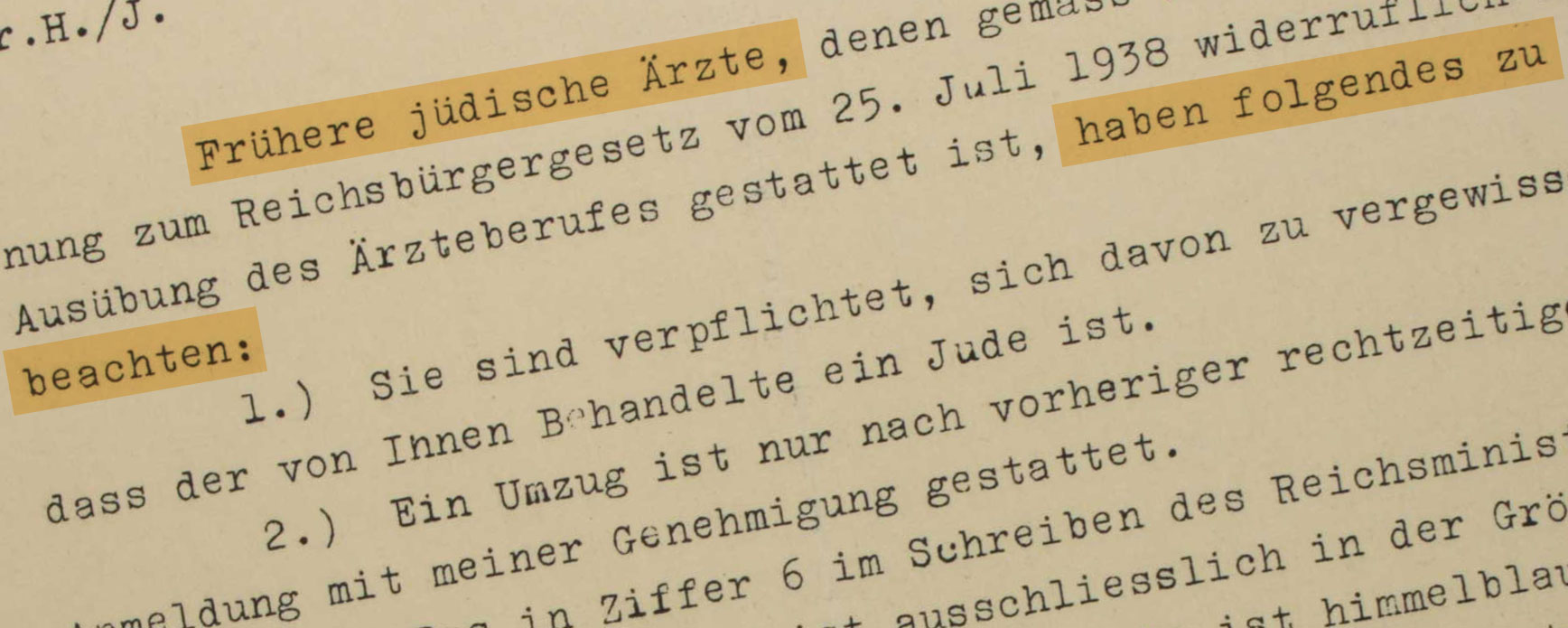

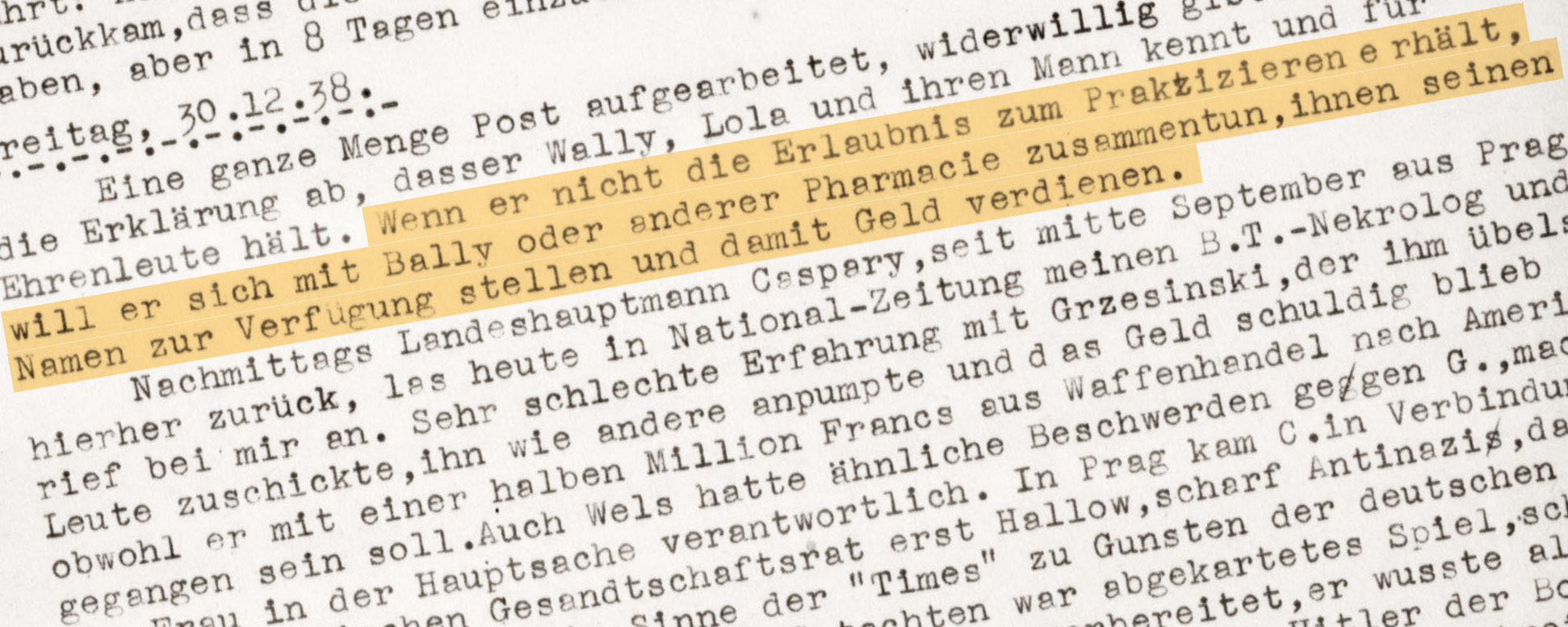

“If he [Dr. Selmar Aschheim] does not get permission to practice, he will team up with Bally or another pharmacy, allow them to use his name and make money with it.”

Paris

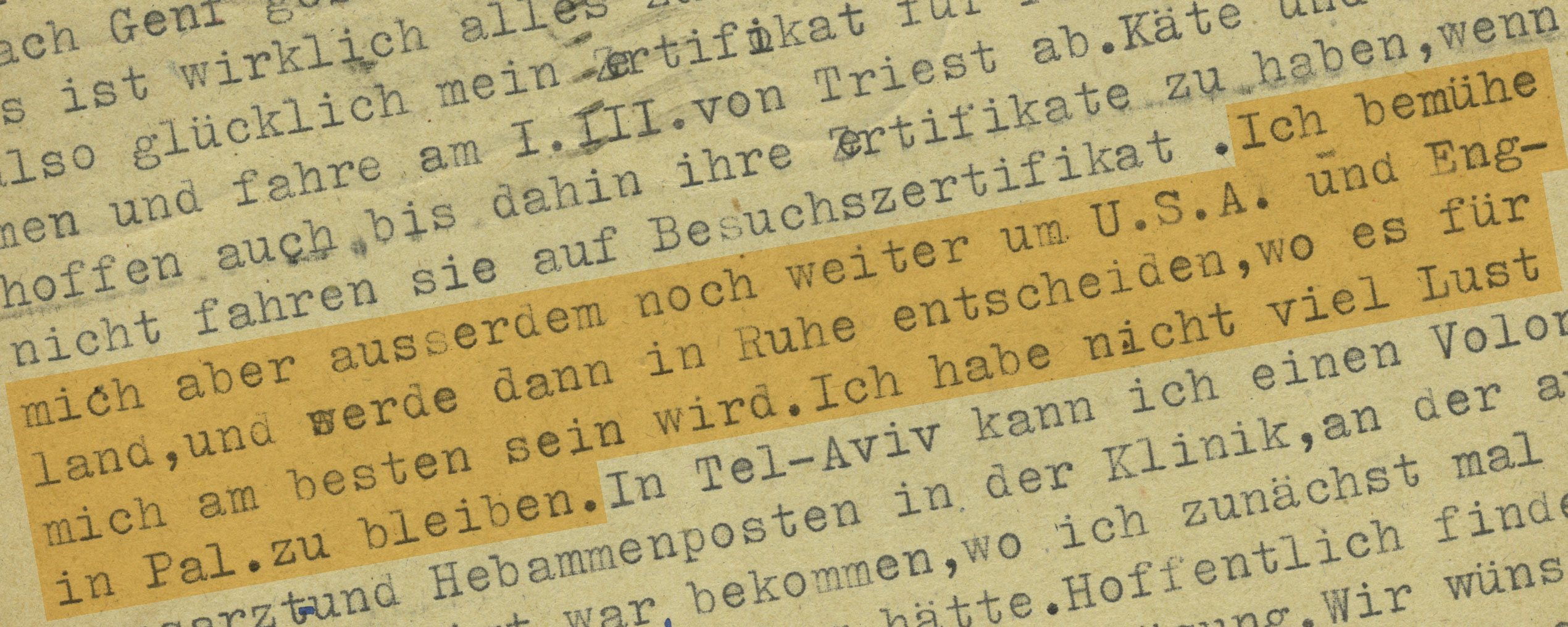

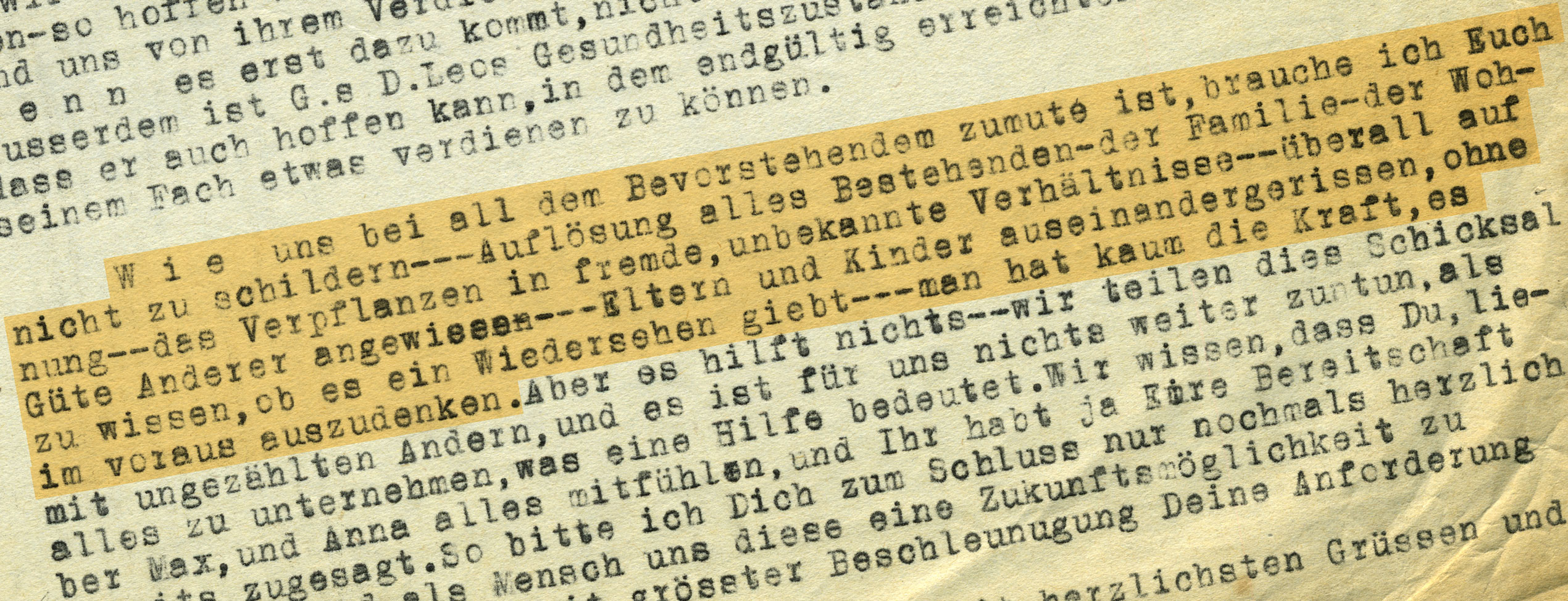

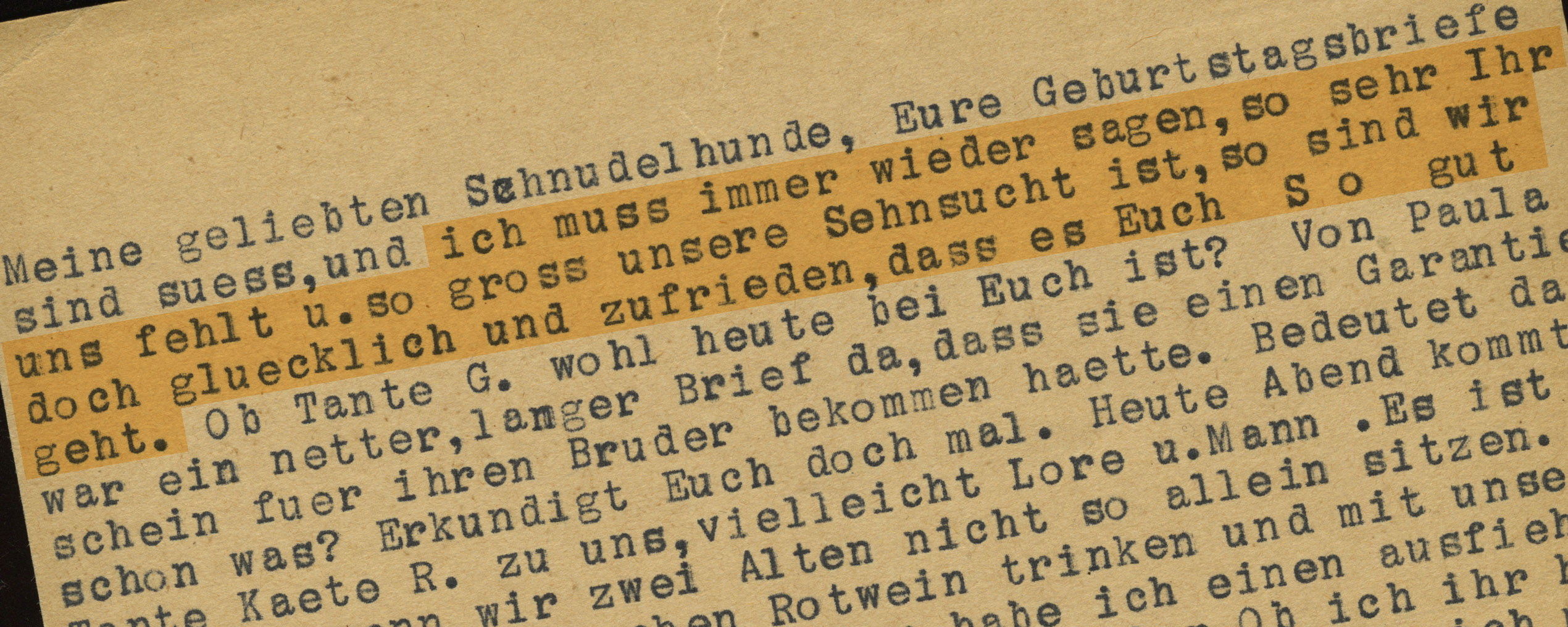

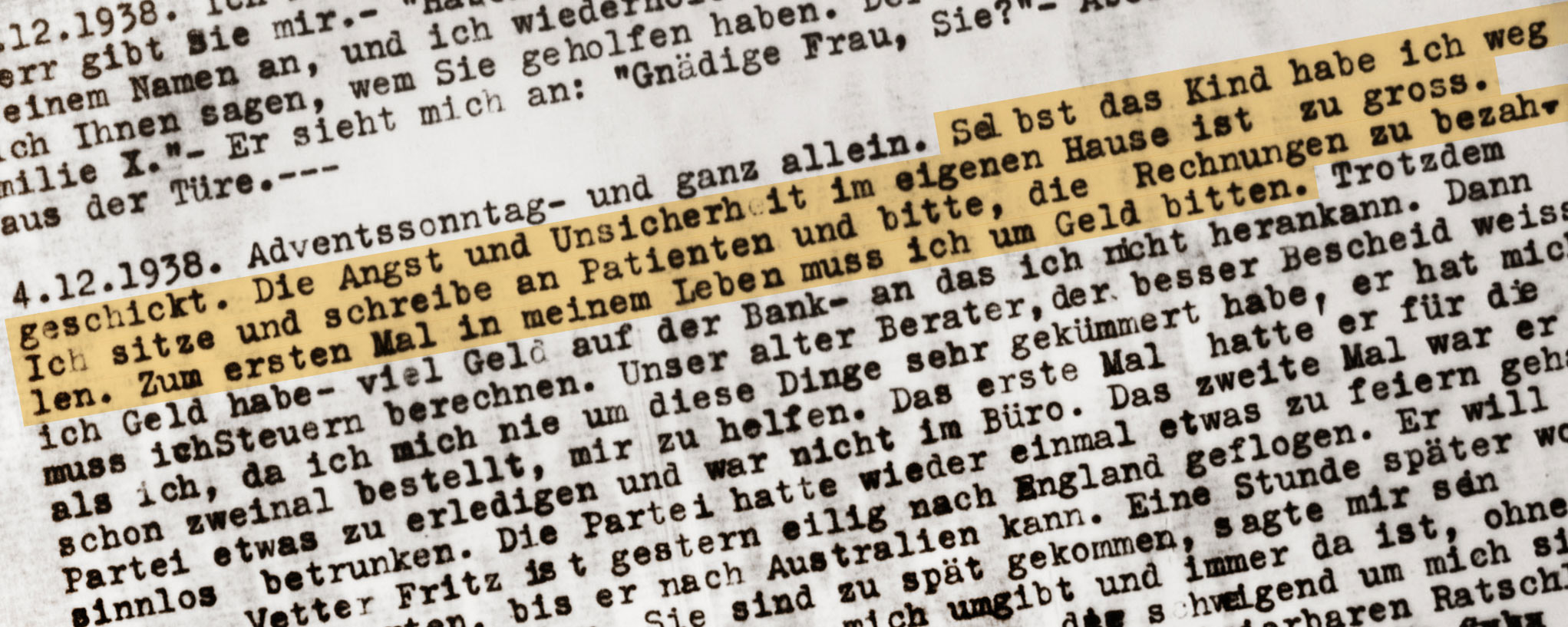

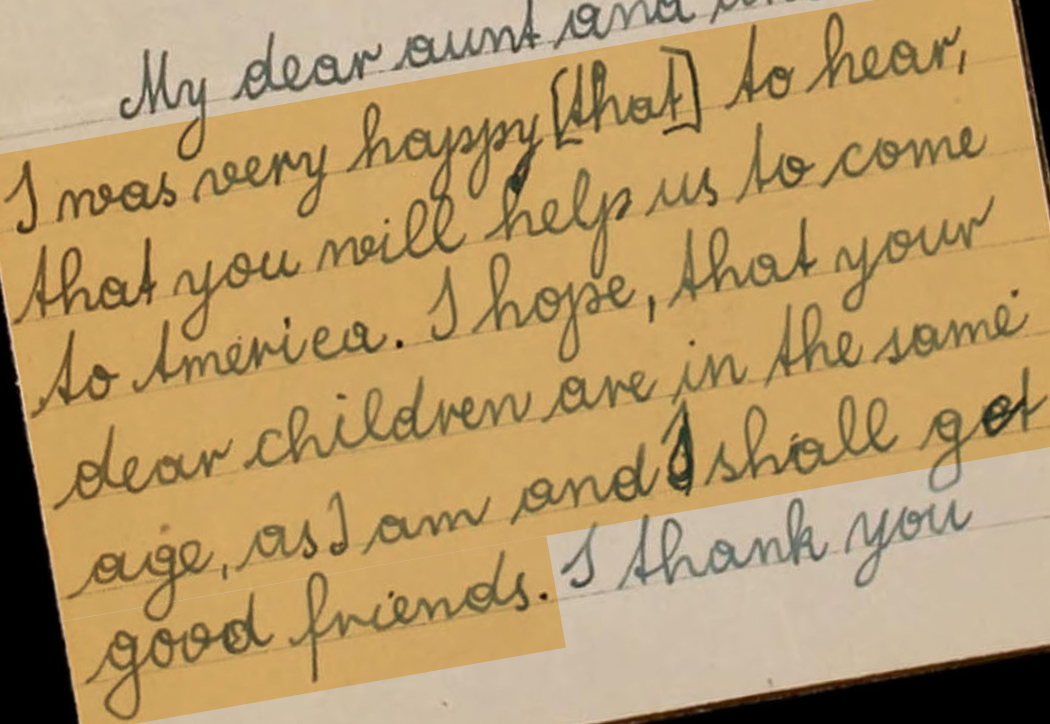

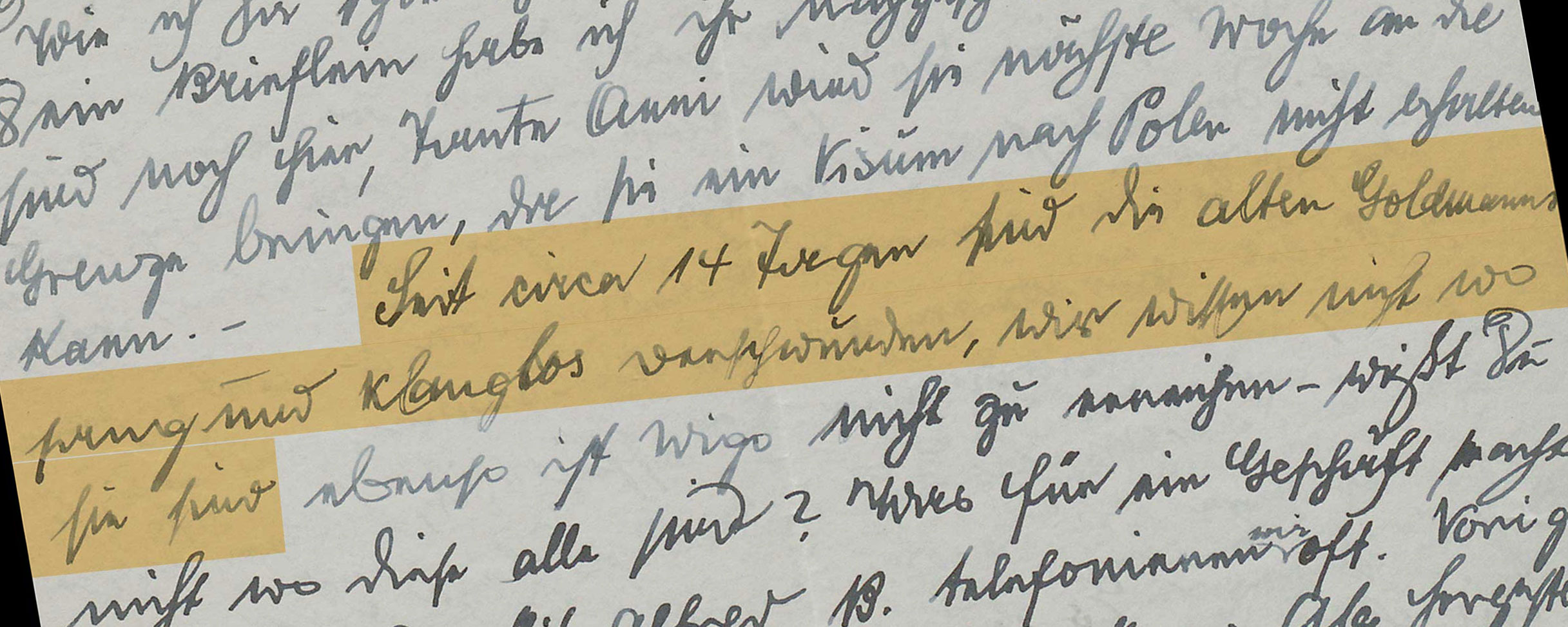

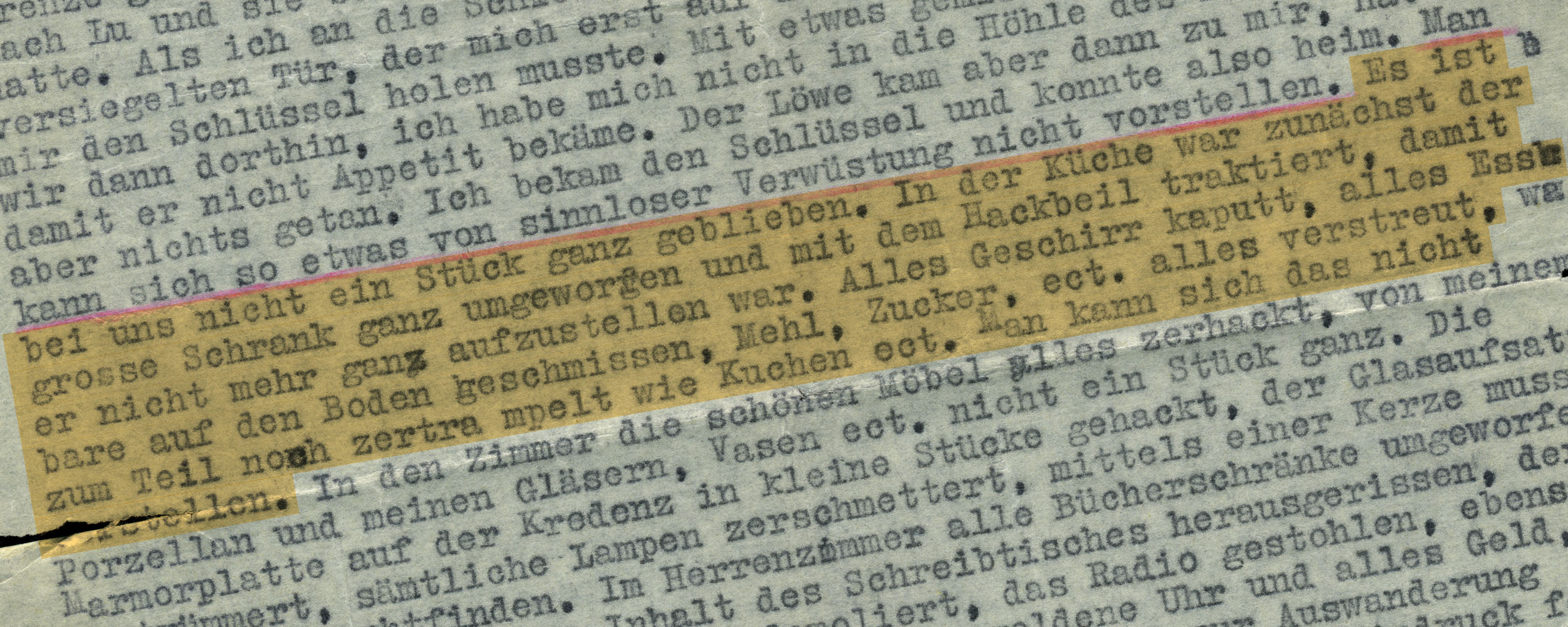

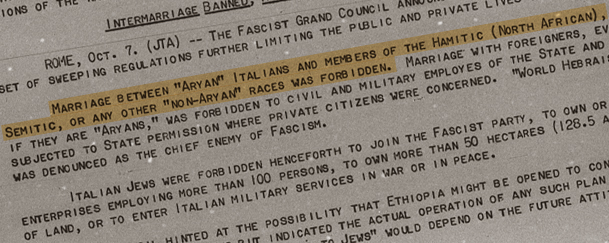

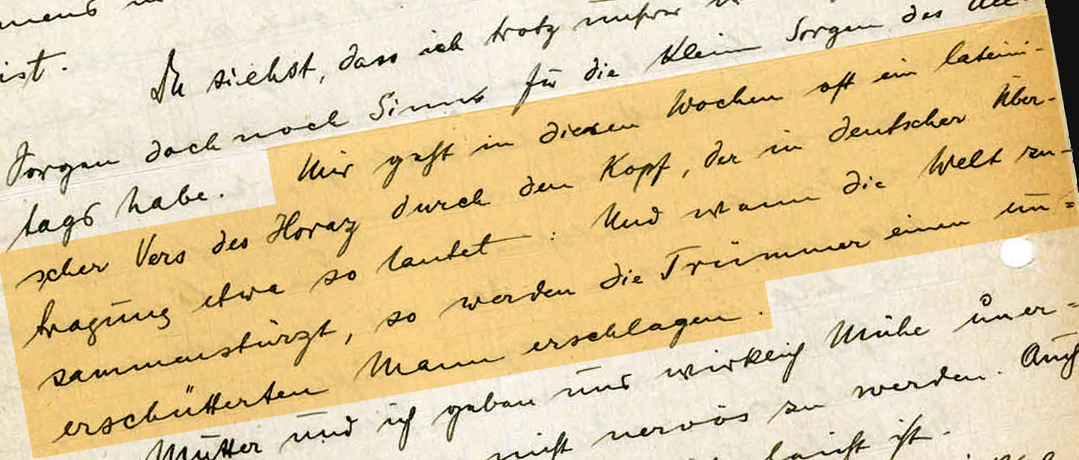

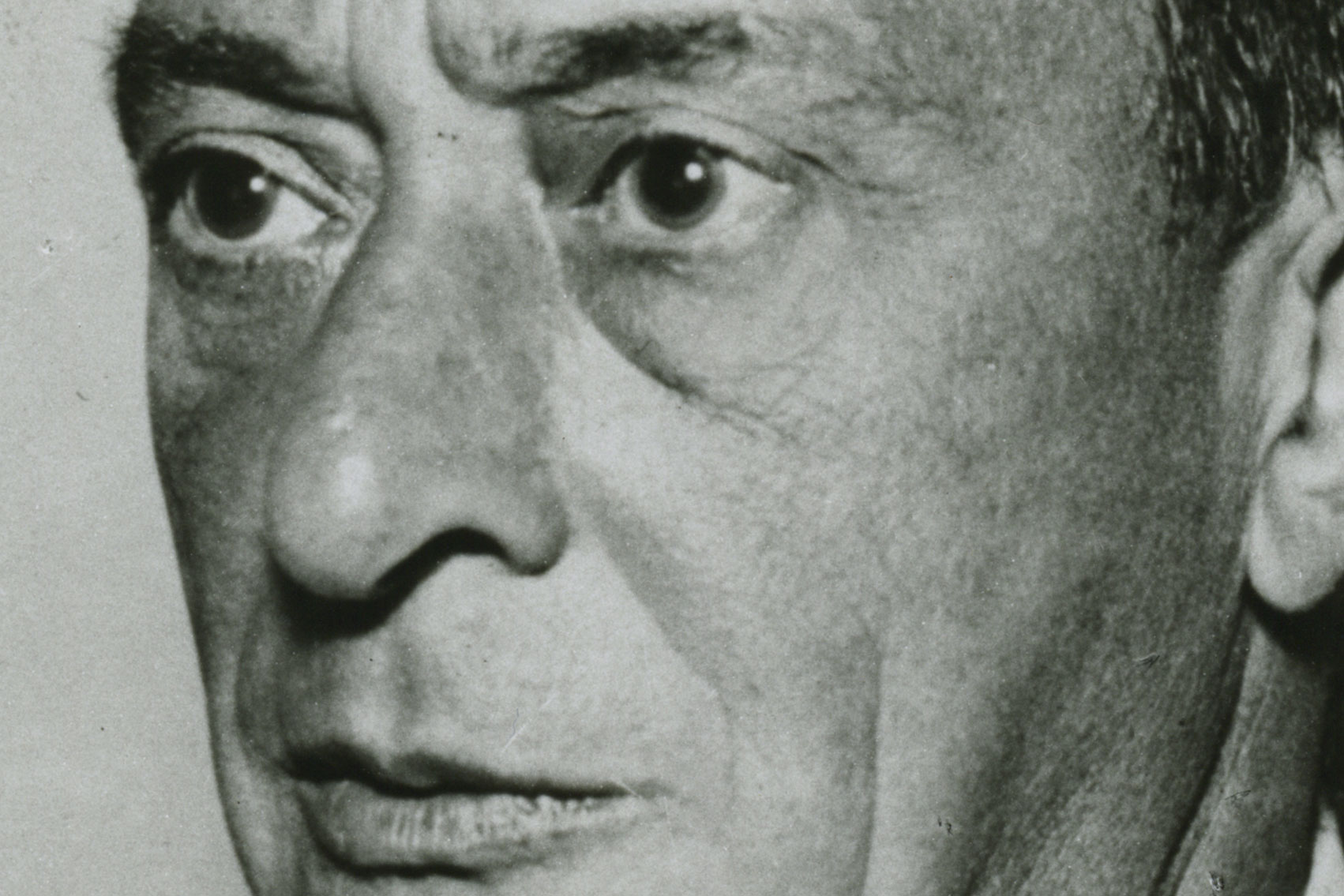

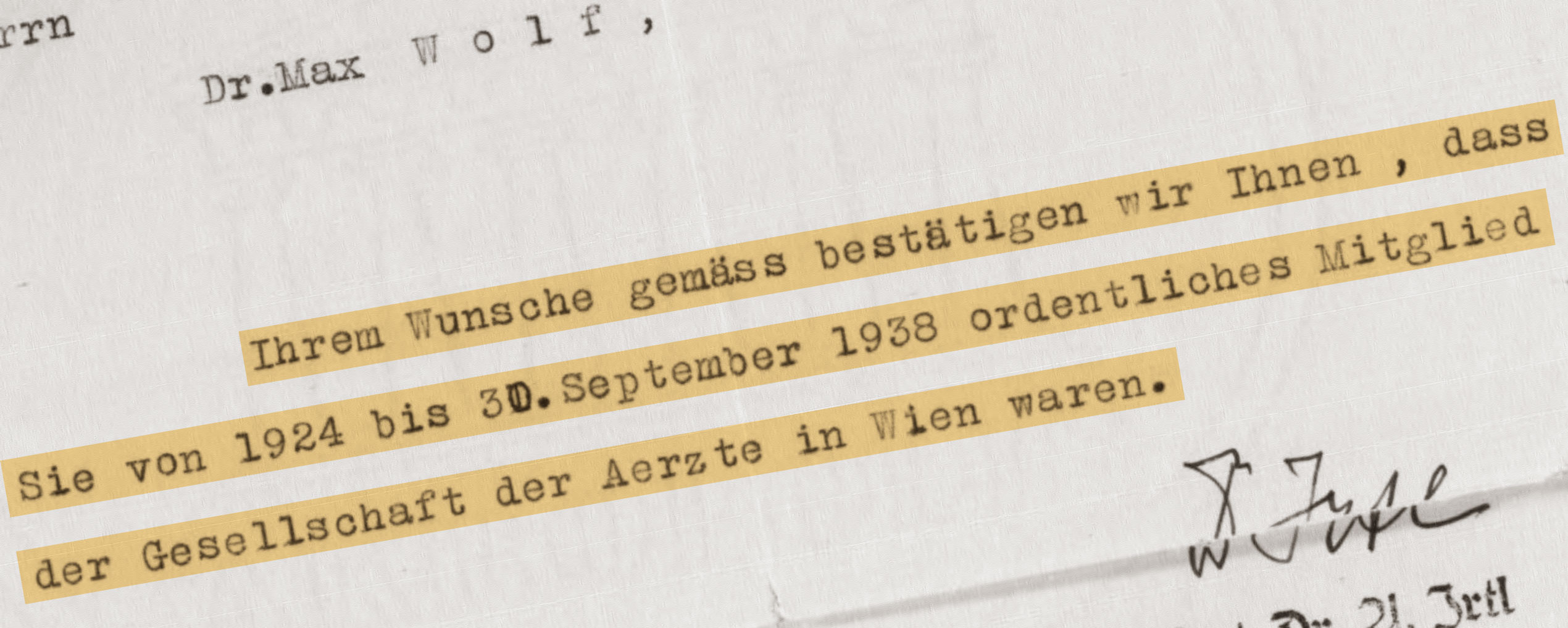

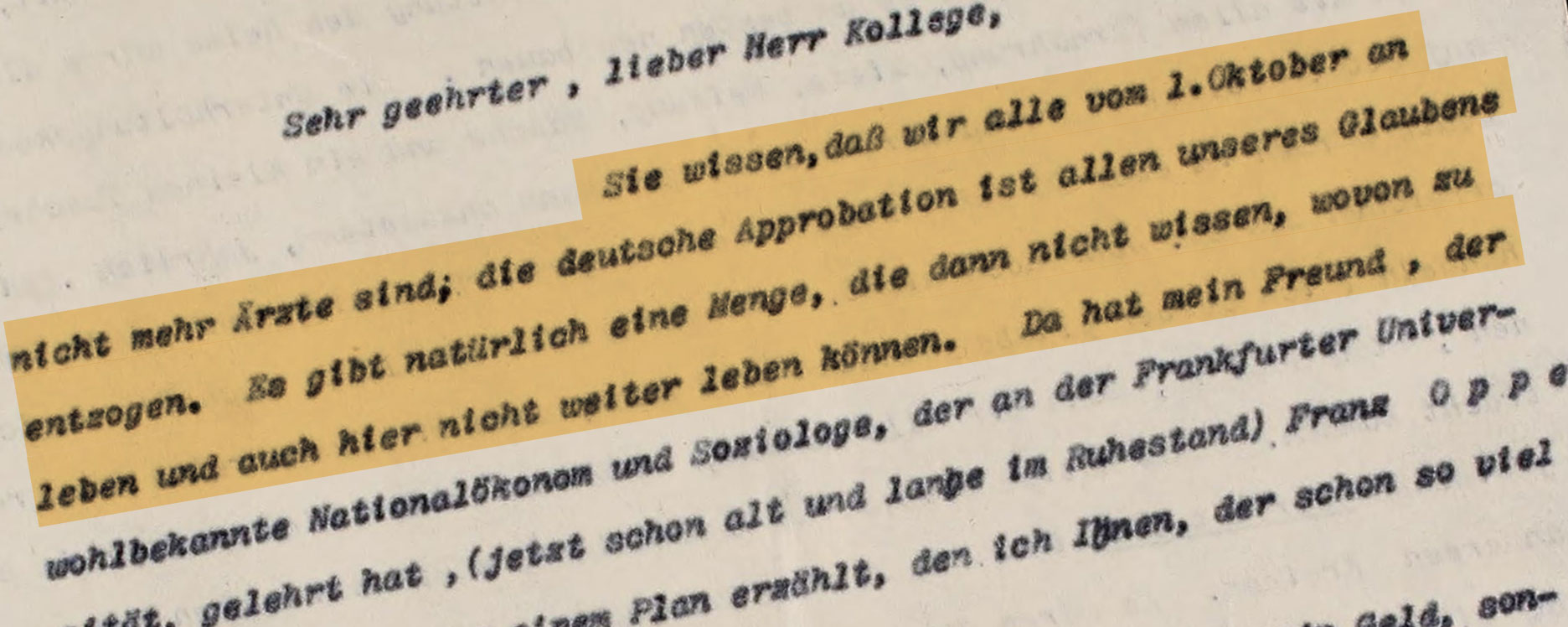

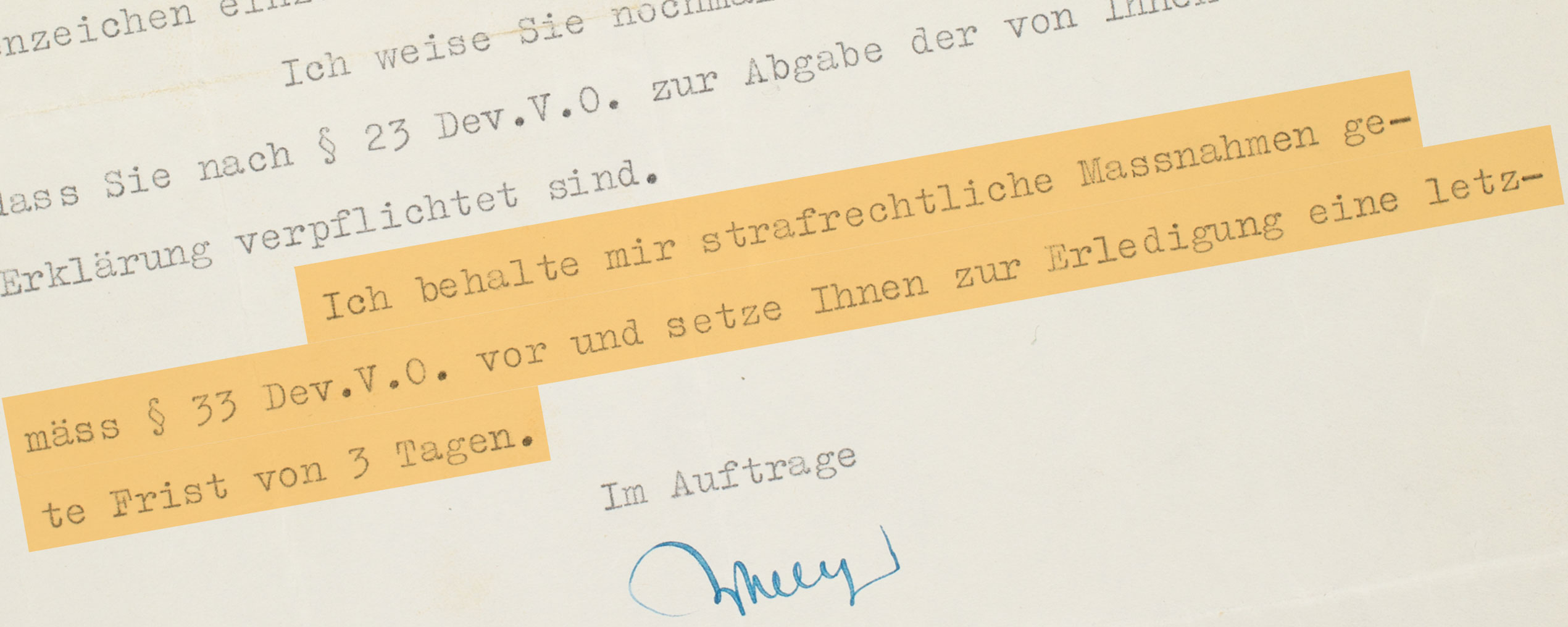

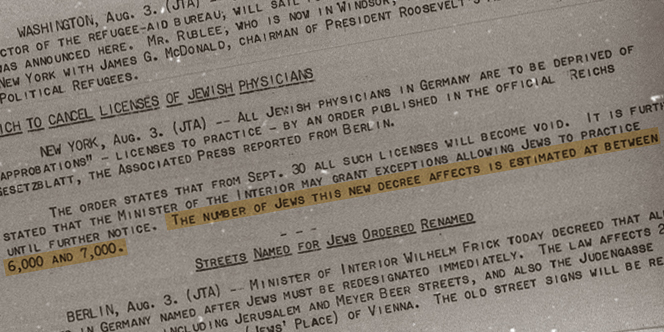

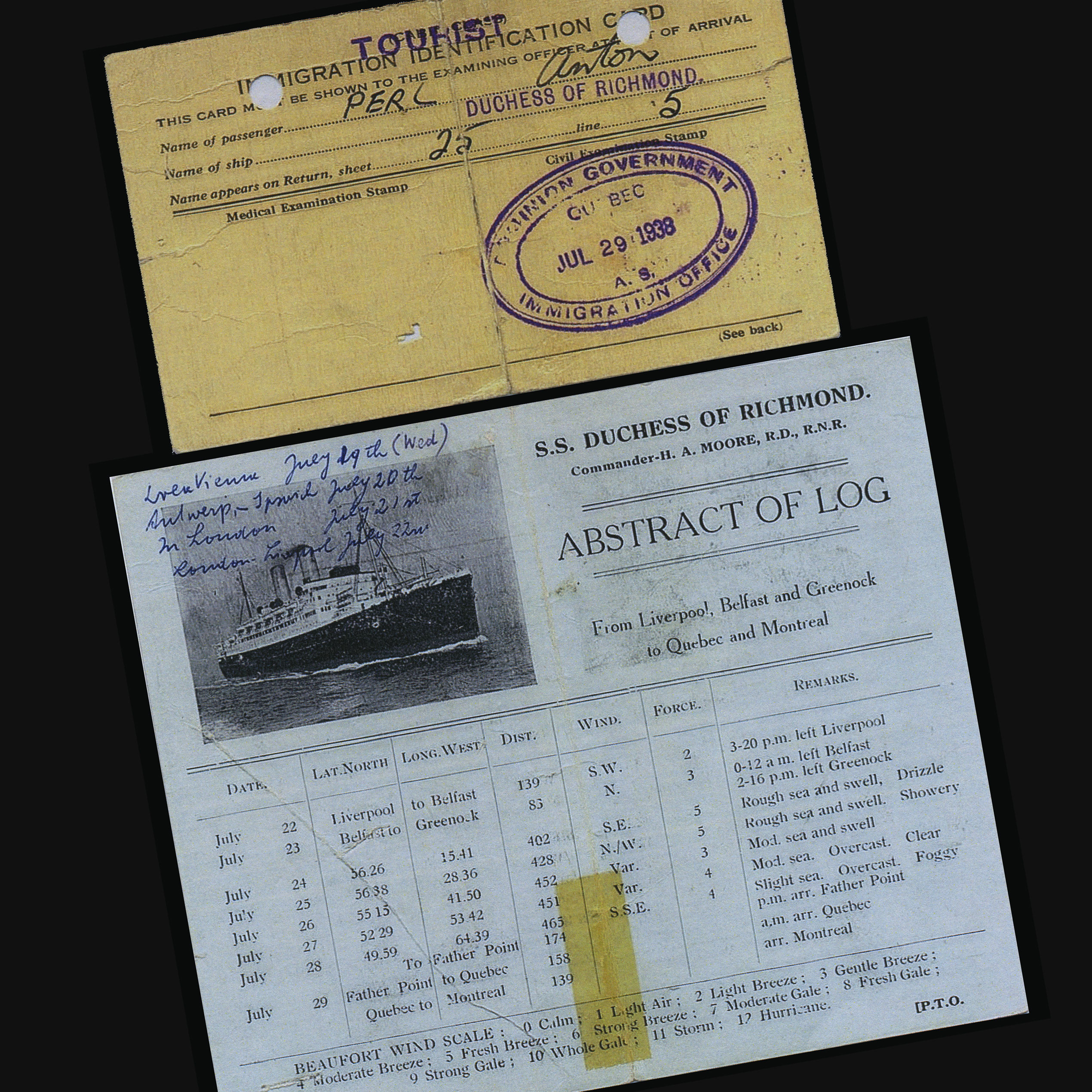

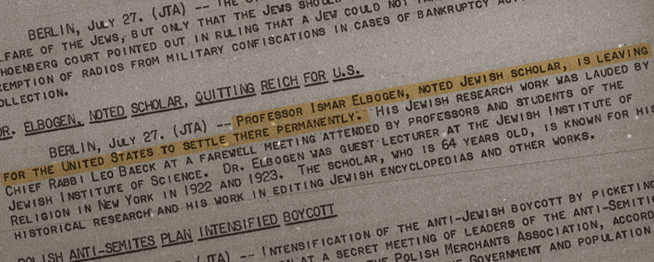

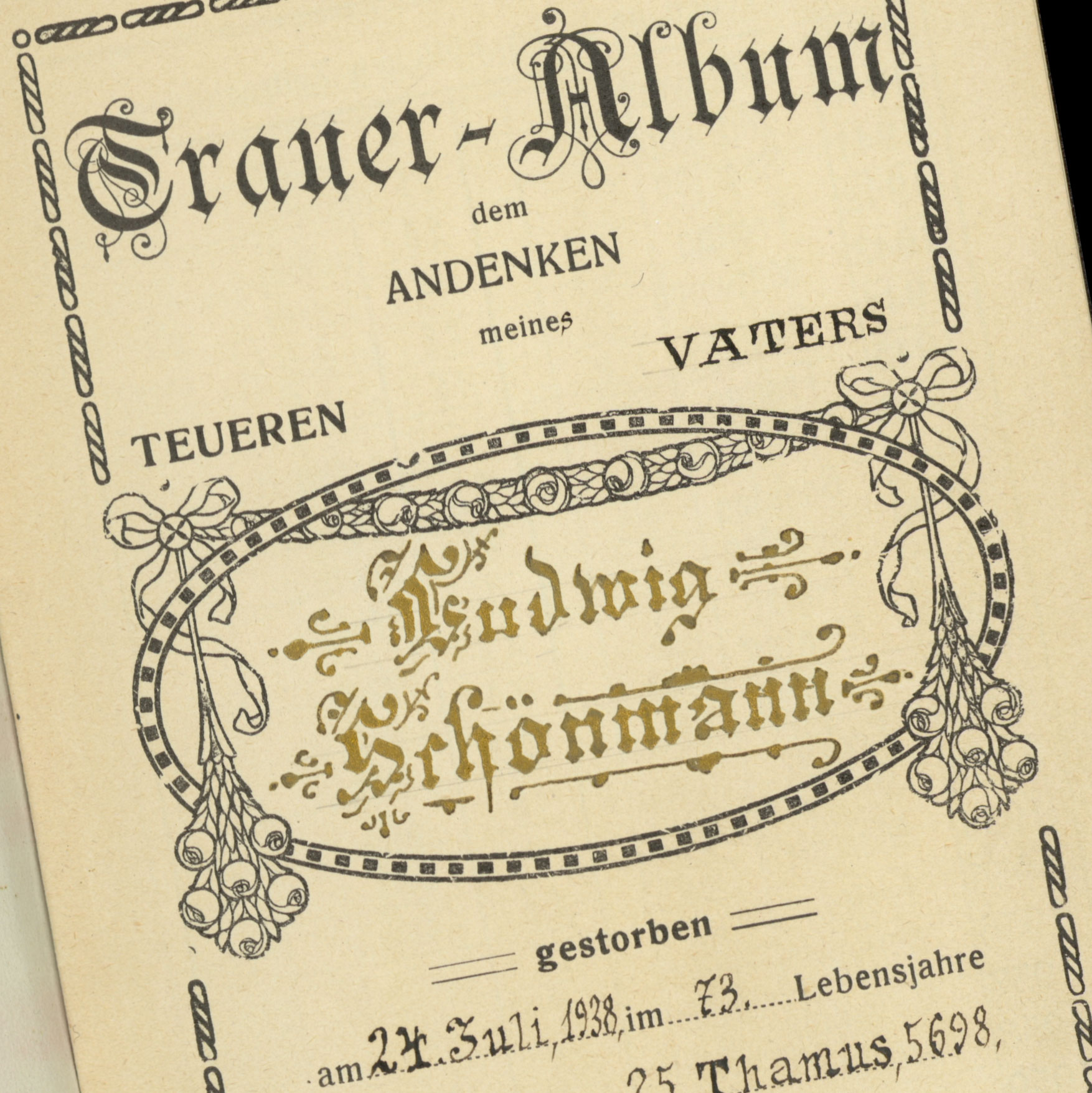

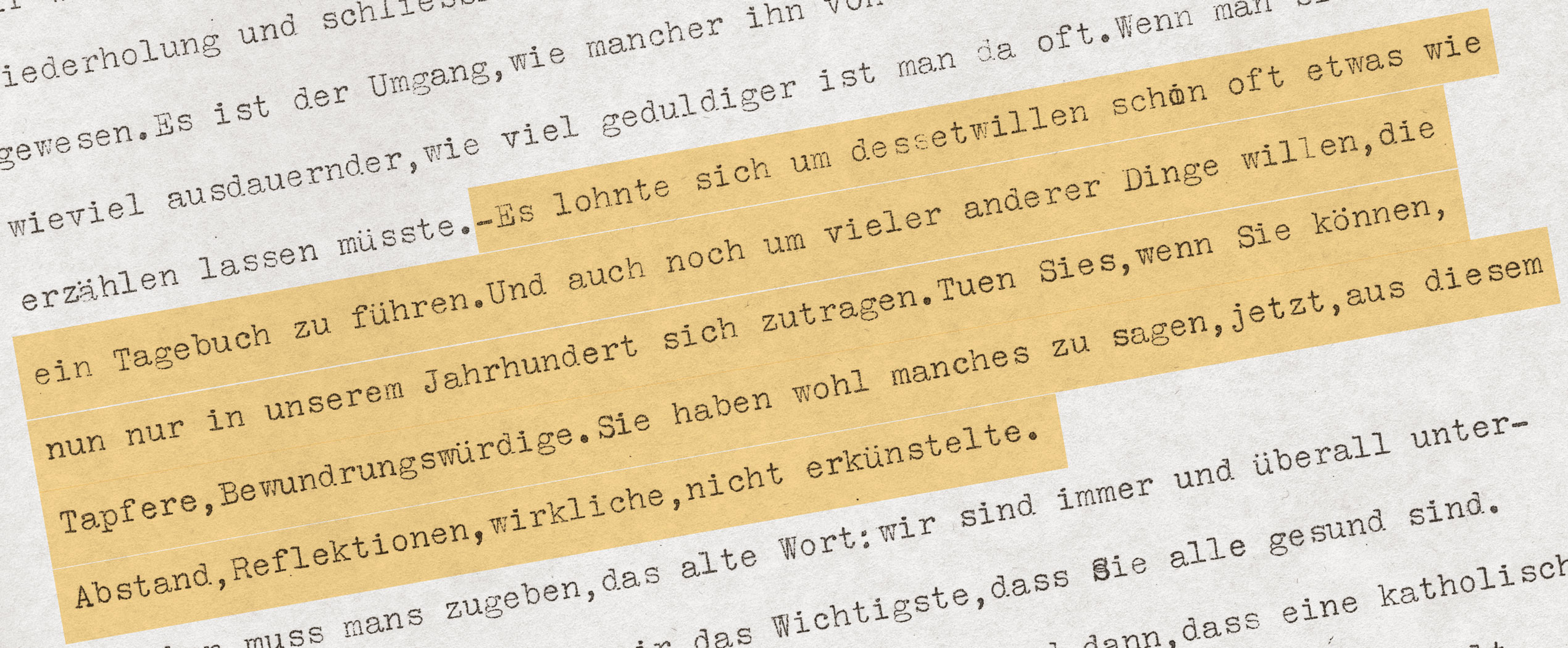

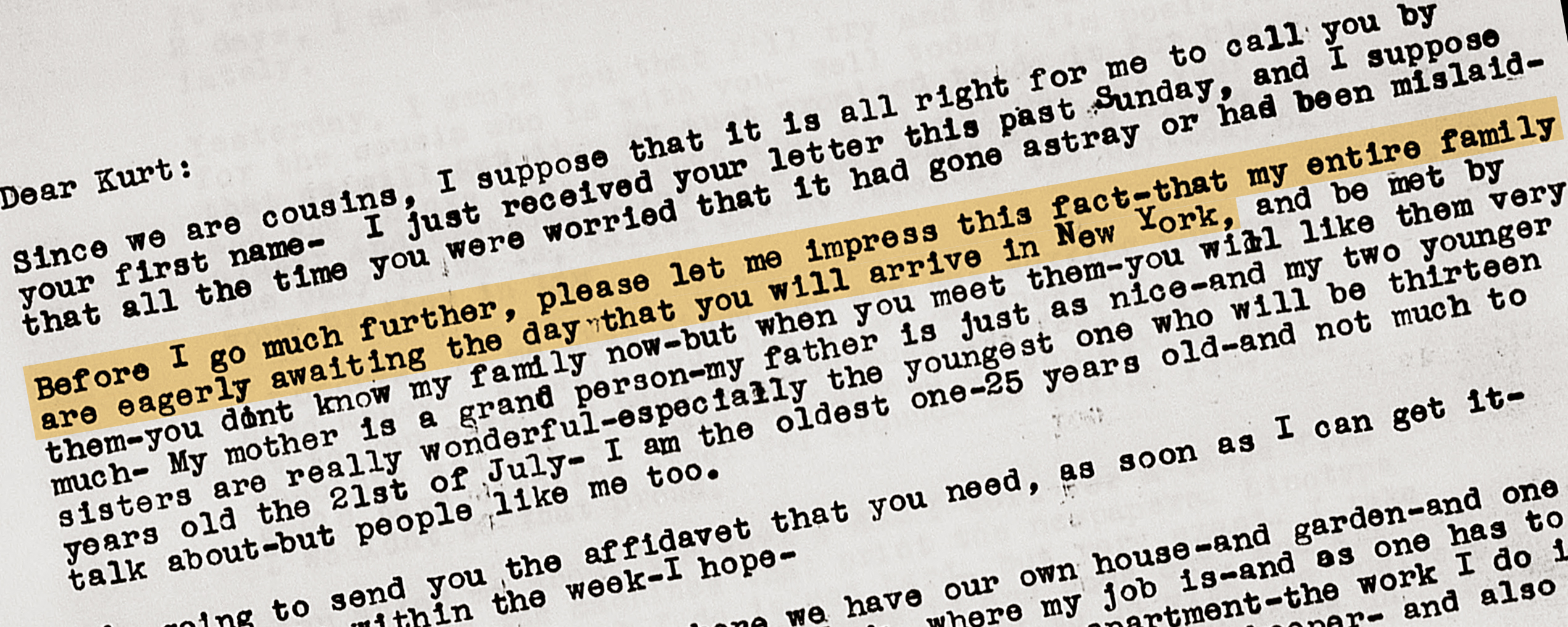

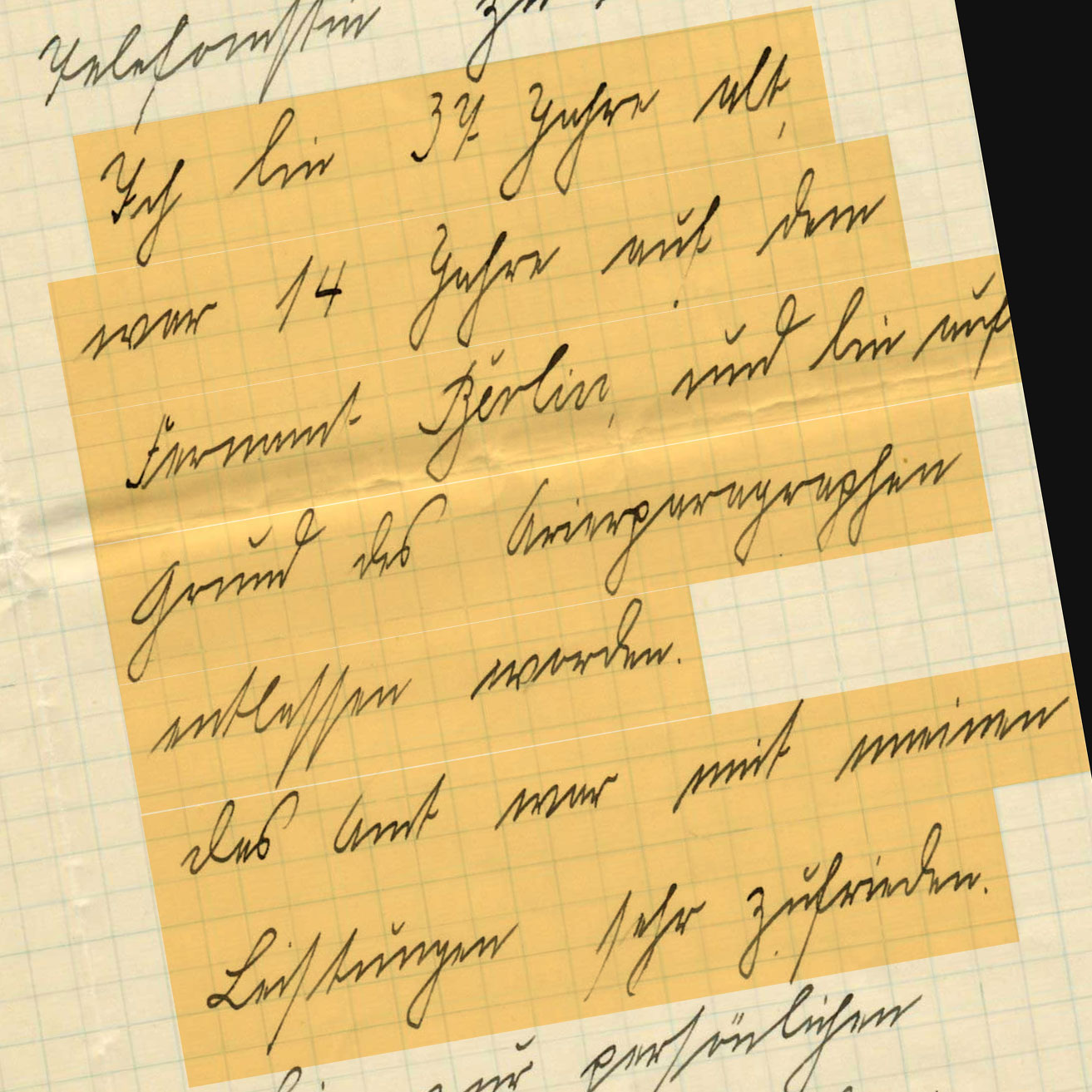

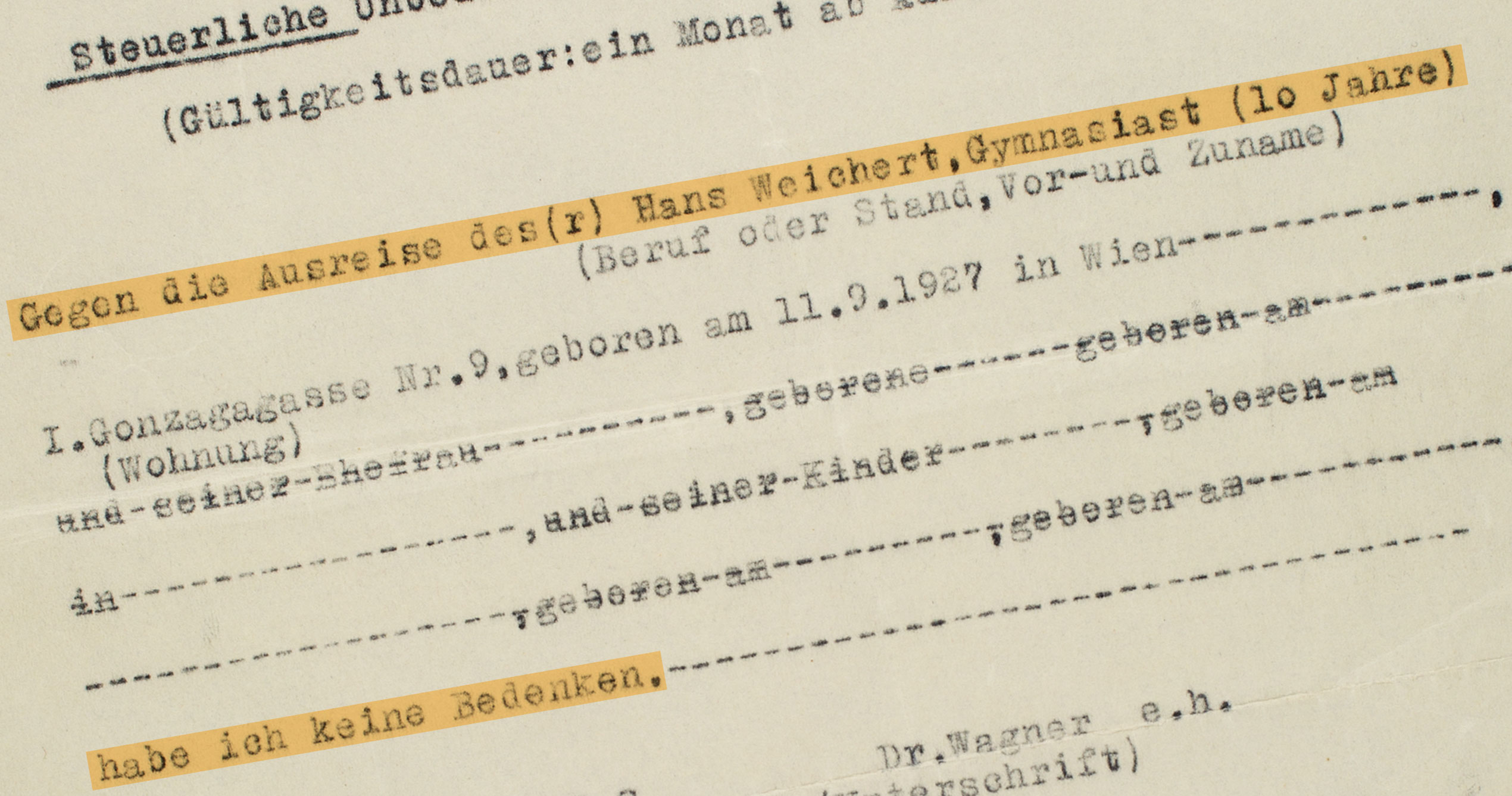

One of the first official acts of the new Nazi rulers in 1933 had been the elimination of the independent press. Already in February, the freedom of the press was abolished, and from October, only such individuals who were deemed politically reliable and could prove their “Aryan” descent were admitted to journalistic professions. Ernst Feder (b. 1881), a jurist and erstwhile editor for domestic affairs at the “Berliner Tageblatt,” fulfilled neither of these requirements. In his Parisian exile, he resumed his activities as a journalist as one of the founders of the German-language Pariser Tageblatt (1933-36) and as a freelance writer. On the pages of his diary, he covers a plethora of topics, ranging from the personal to the philosophical and political. Among his friends and fellow exiles was the gynecologist and endocrinologist, Dr. Selmar Aschheim (b. 1878). As Feder notes in his diary on December 30th, the eminent physician and scientist was looking for an alternative source of income, should he be denied the possibility to practice in France. Especially older emigrants often had to overcome major obstacles in order to gain a foothold abroad. Language barriers and admission examinations, for which decades of professional experience were not seen as a substitute, additionally exacerbated the situation.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Ernst Feder Collection, AR 7040 / MF 497

Original:

Box 1, Diary, vol. 13, 1938