No coming back

Polish parliament passes a new bill against Jewish returnees

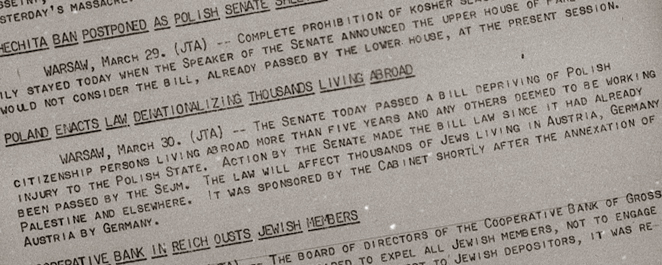

“The law will affect thousands of Jews living in Austria, Germany, Palestine and elsewhere.”

Warsaw

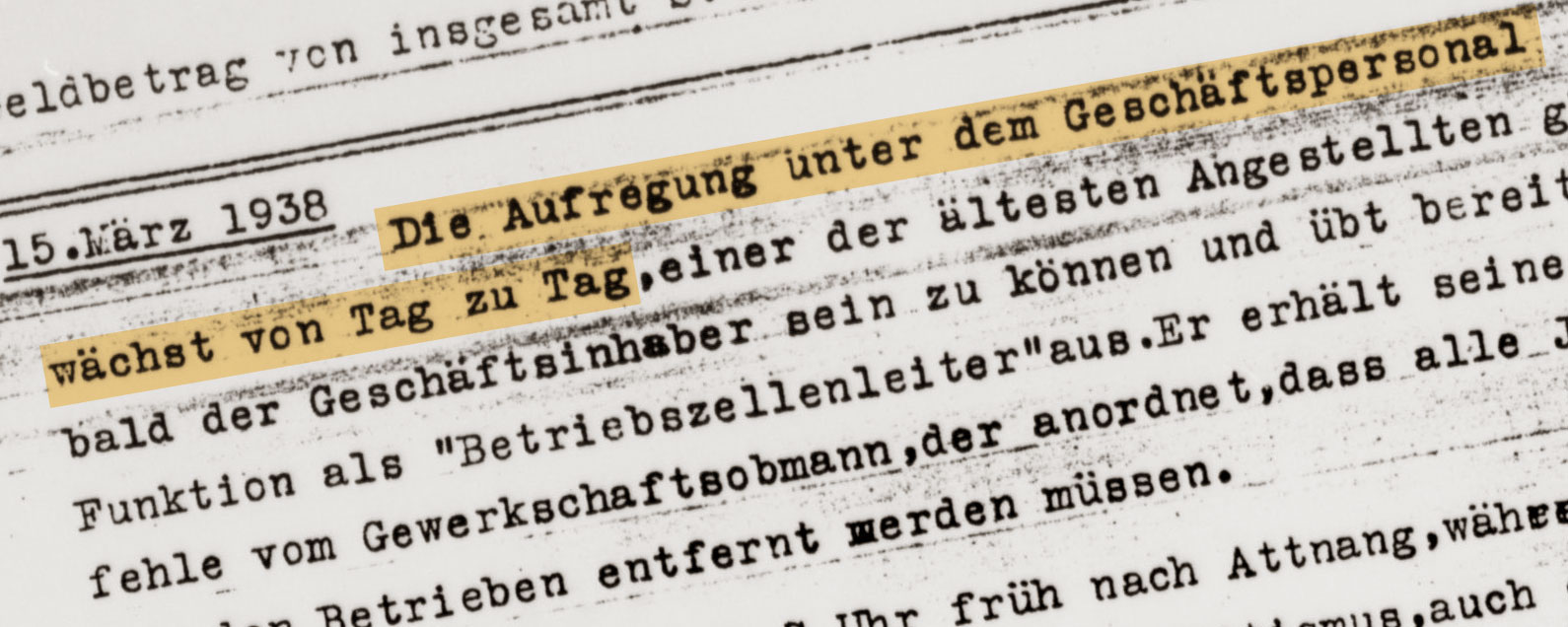

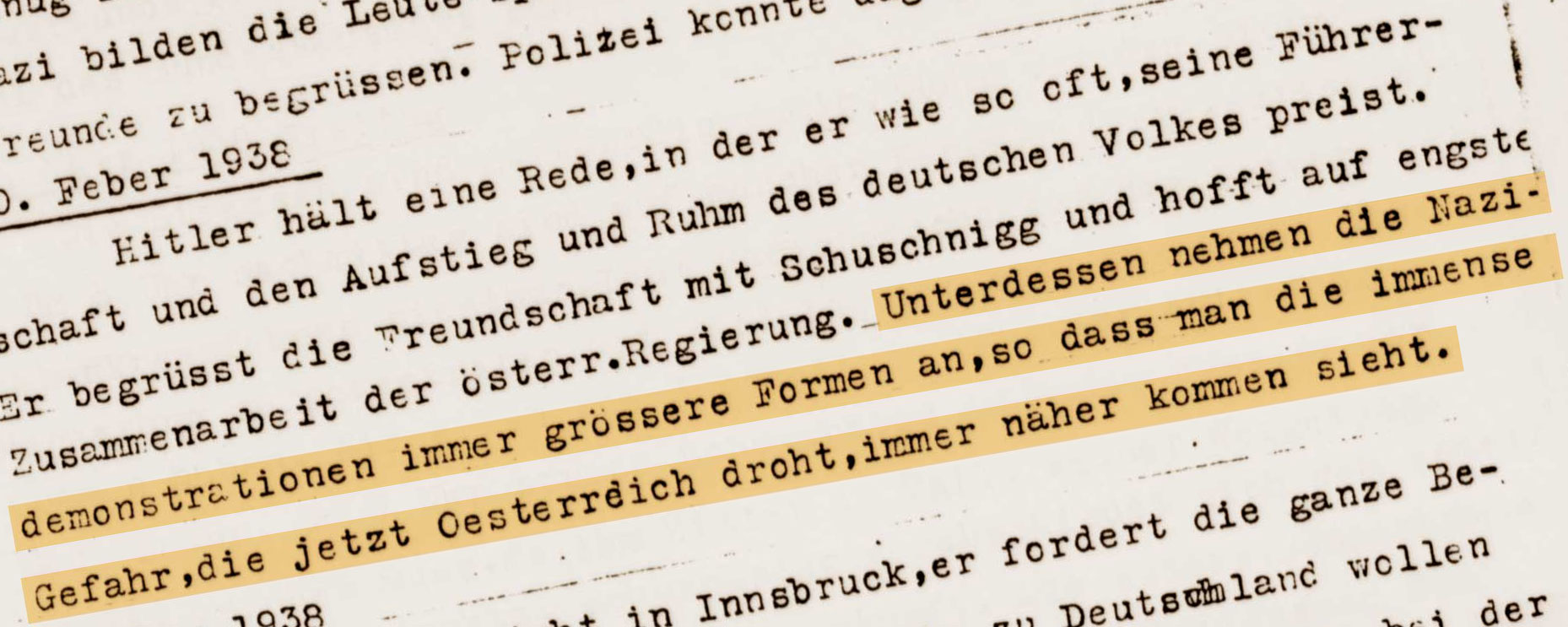

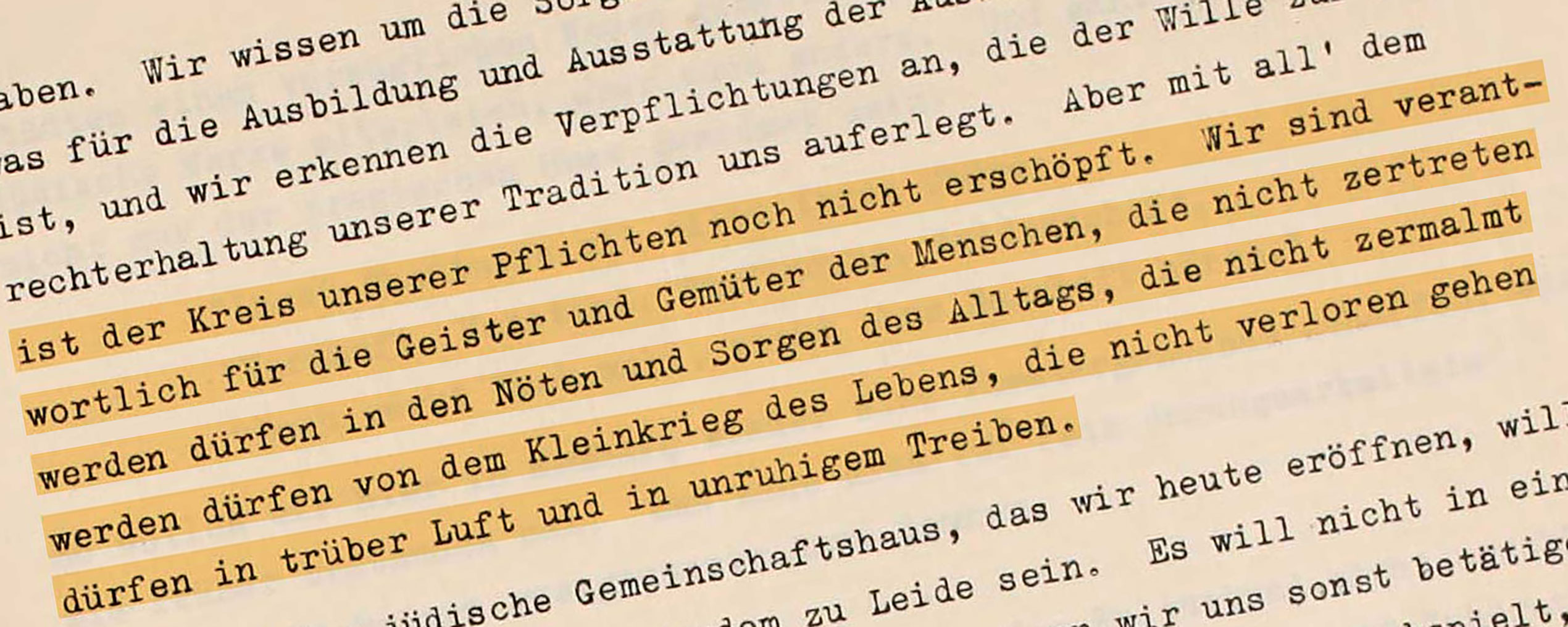

In the wake of Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany, the Polish parliament (“Sejm”), fearing the return of up to 20,000 Polish citizens from Austria, passed a bill according to which Poles who had lived abroad for more than five years were to lose their citizenship. The situation of the Jews had improved somewhat under the Piłsudski government (1926–1935), but after the marshal’s death, especially in the atmosphere created by the “Camp of National Unity” (from 1937 onward), antisemitism was resurgent. Universities applied quotas to Jewish students and introduced “ghetto benches” for them, Jews were held responsible for the Great Depression, Jewish business were boycotted and looted, and hundreds of Jews were physically harmed, some killed.

SOURCE

Institution:

Collection:

“Poland Enacts Law Denationalizing Thousands Living Abroad”

Source available in English