Bad prospects

Refugees in Czechoslovakia

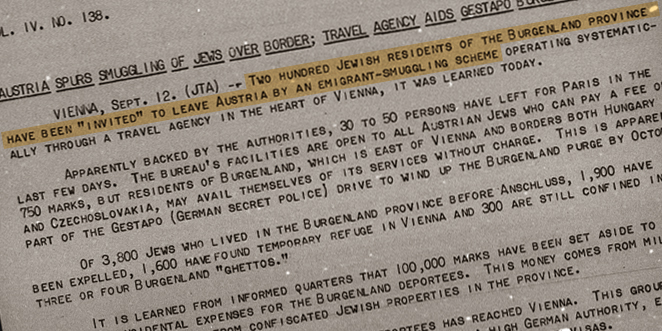

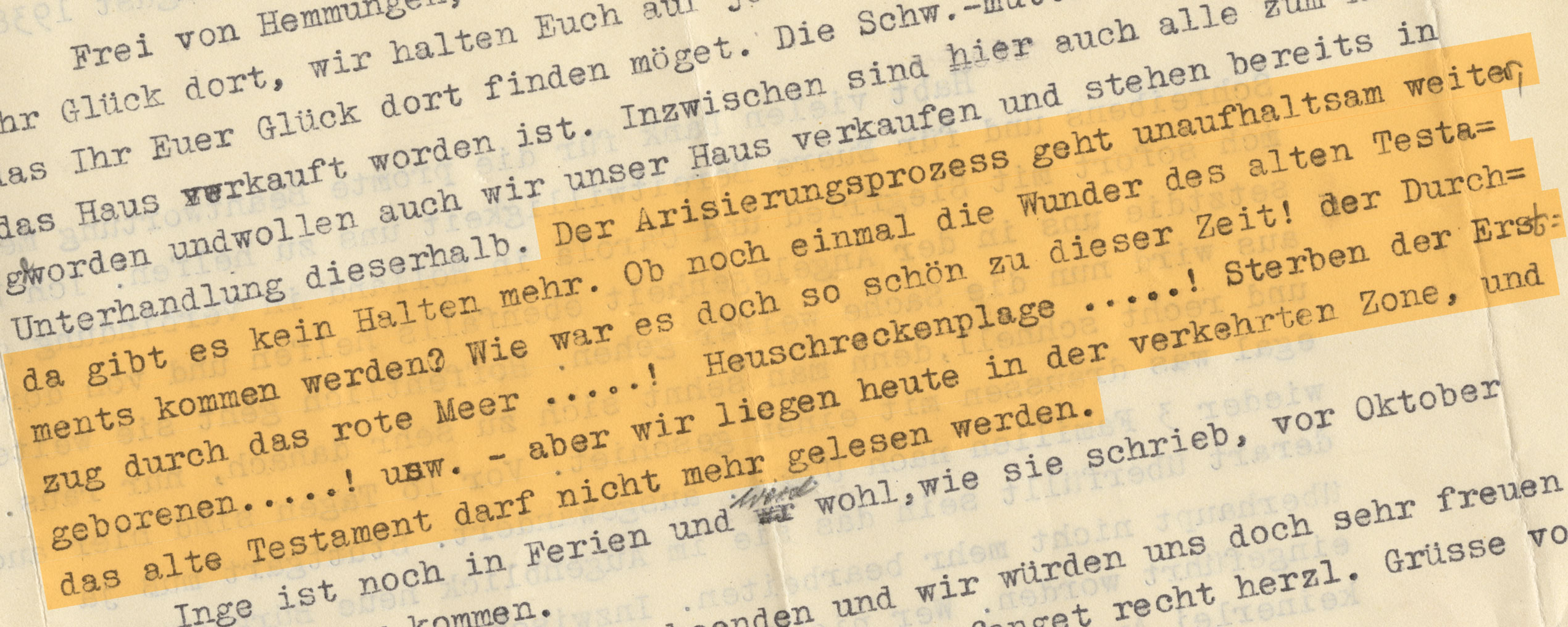

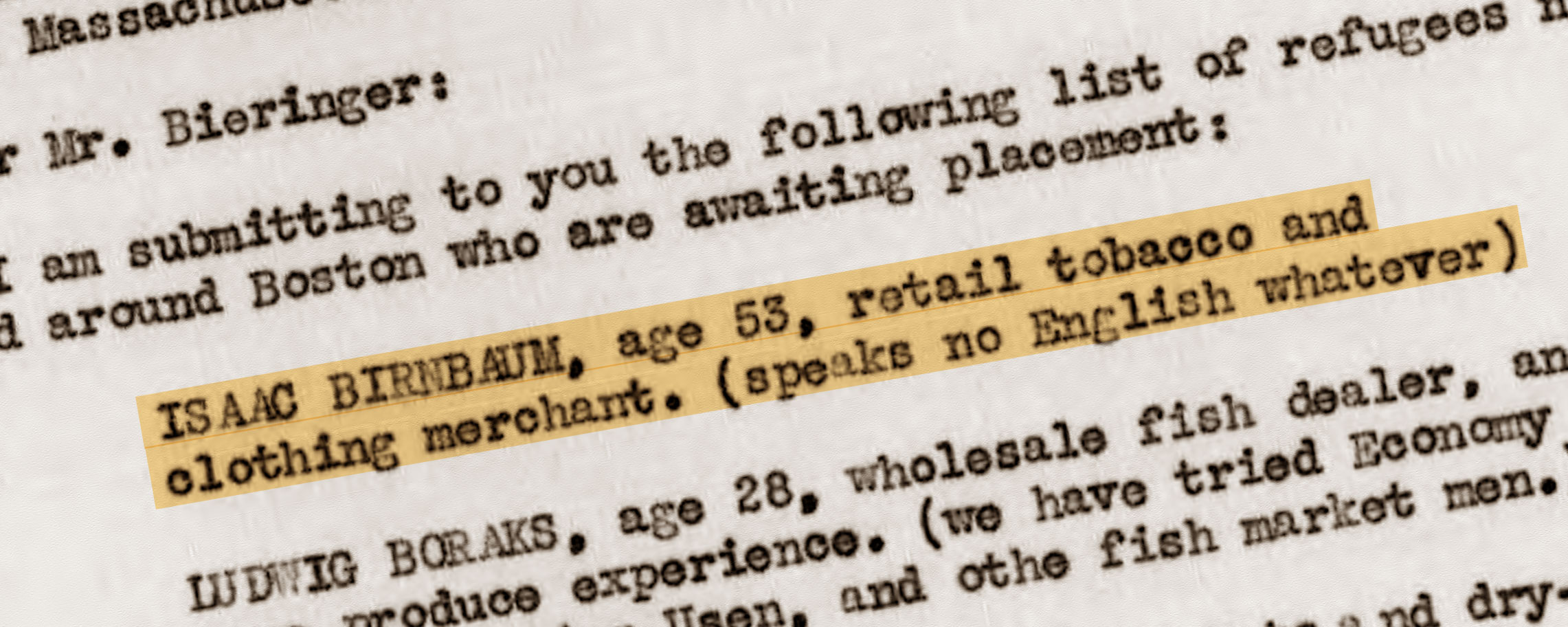

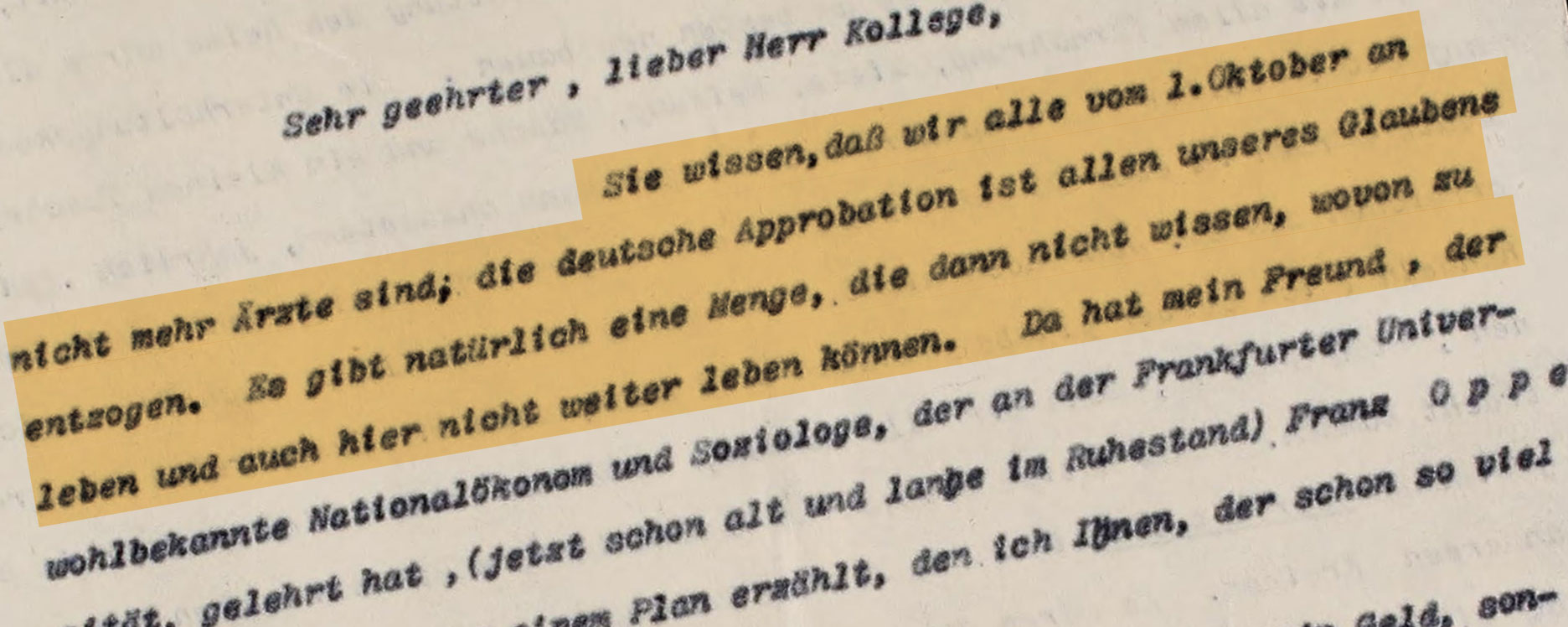

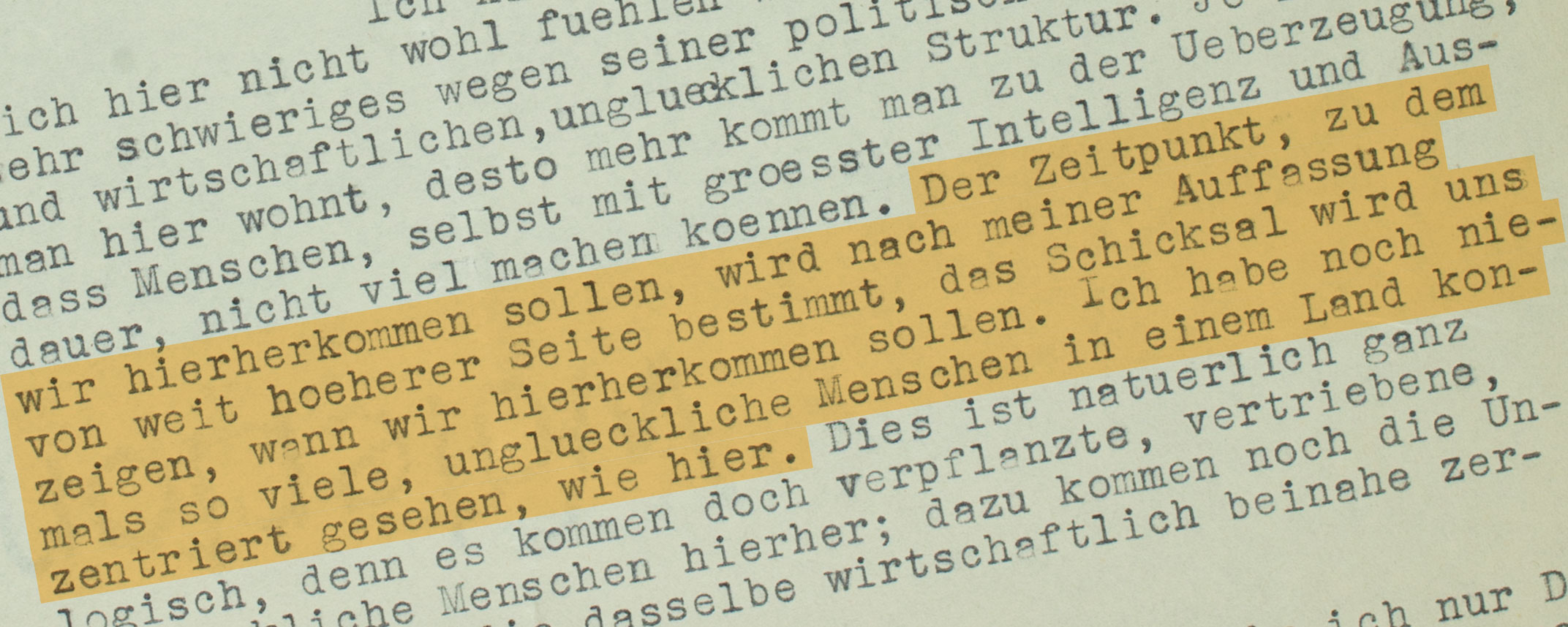

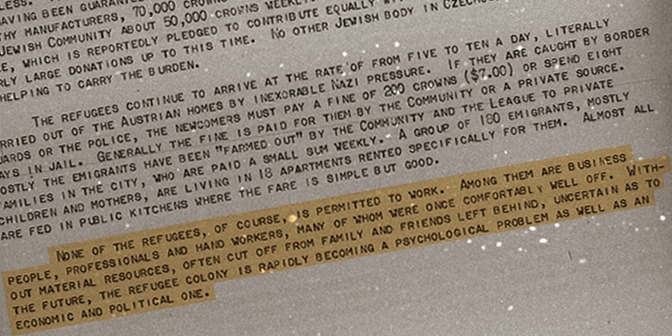

“None of the refugees, of course, is permitted to work. Among them are business people, professionals and craftsmen, many of whom were once comfortably well off. Without material resources, often cut off from family and friends left behind, uncertain as to the future, this refugee colony is rapidly becoming a psychological problem as well as an economic and political one.”

Brno (Brünn)

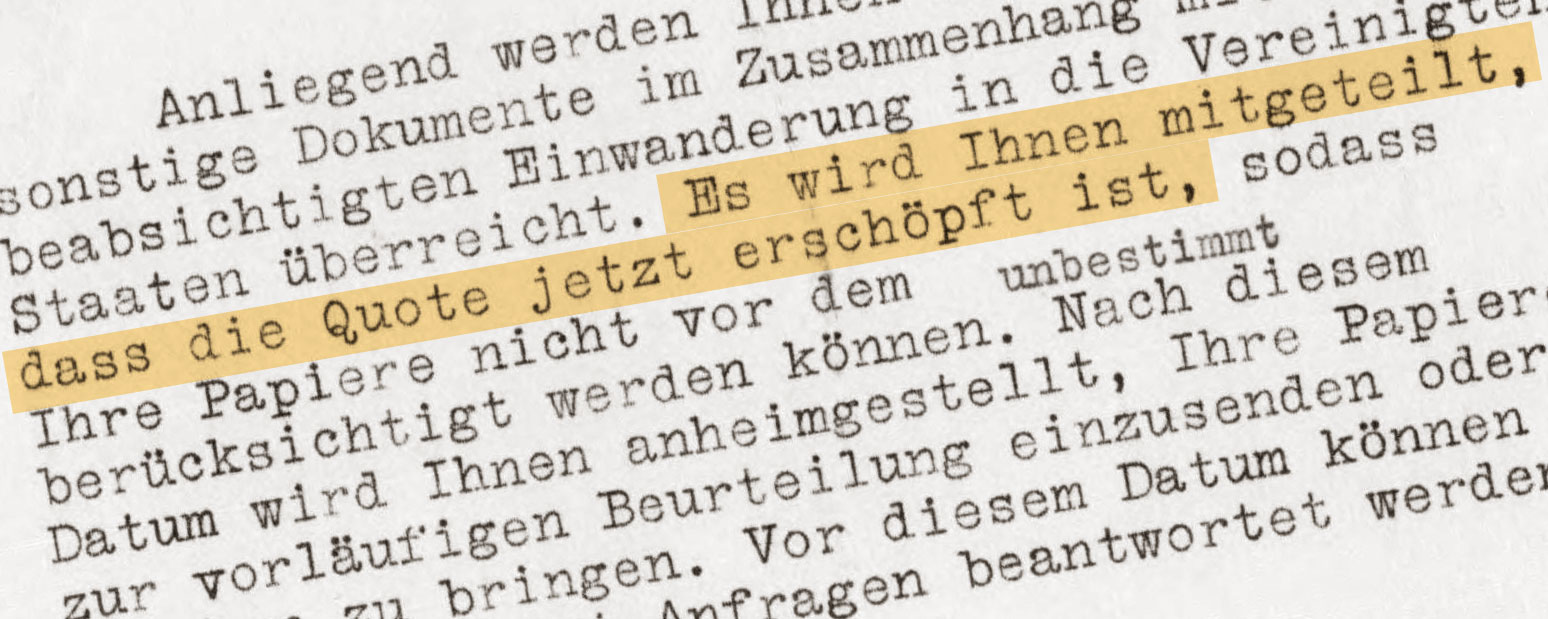

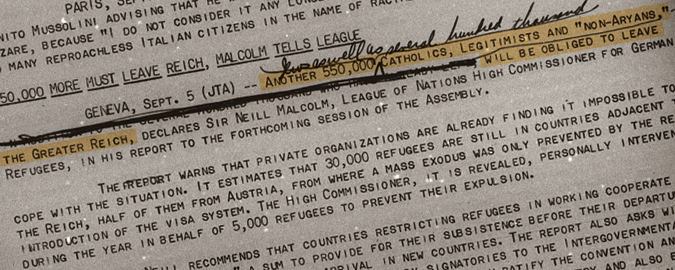

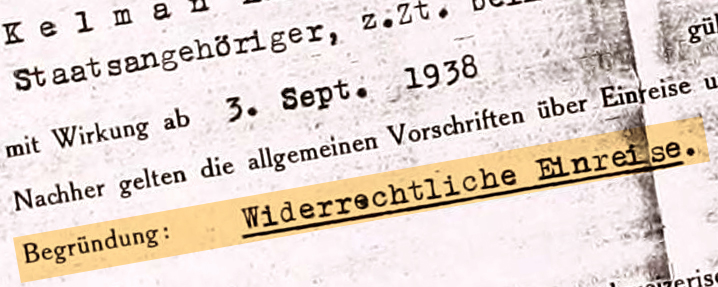

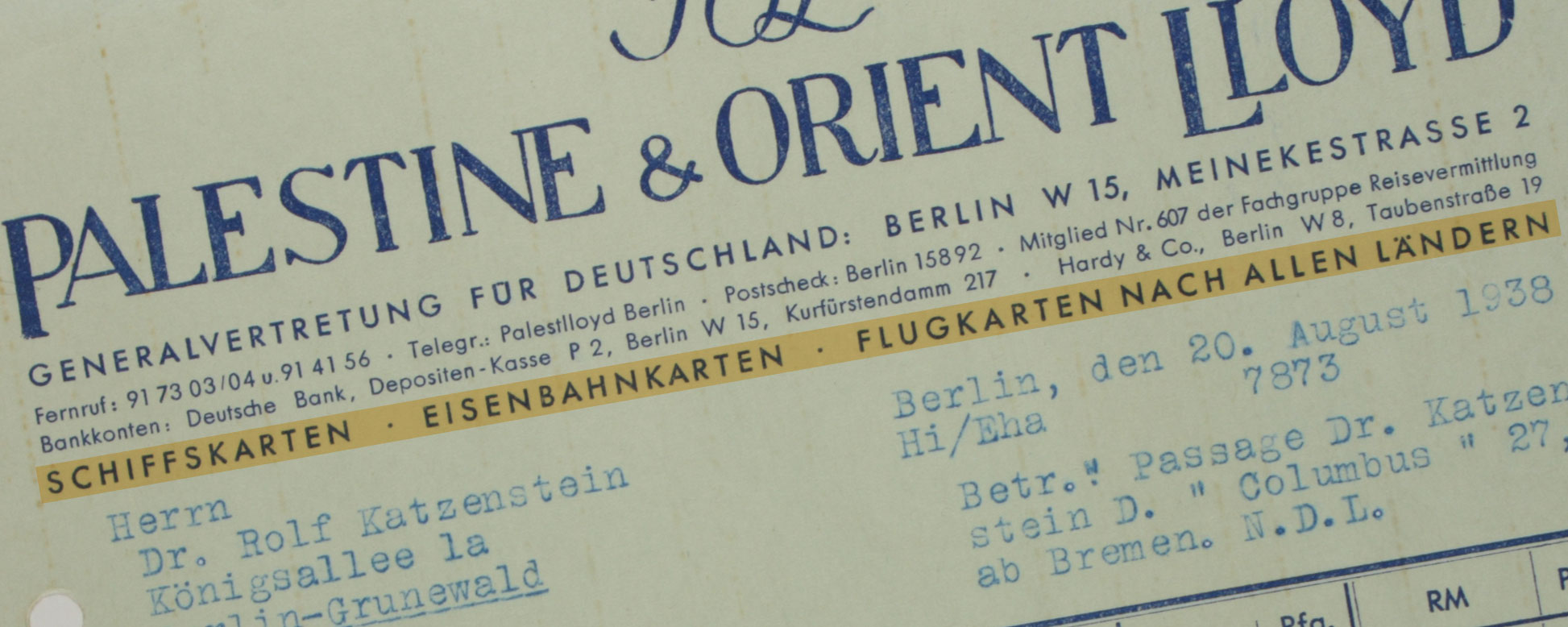

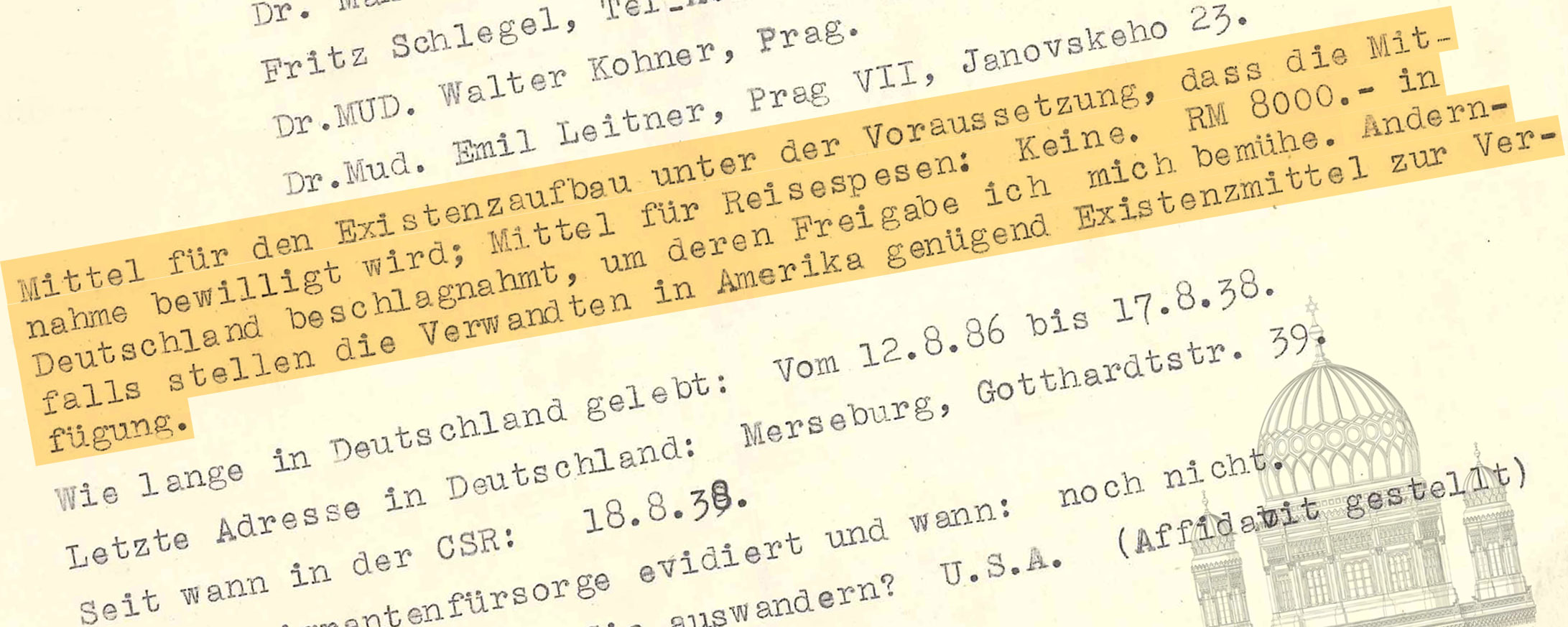

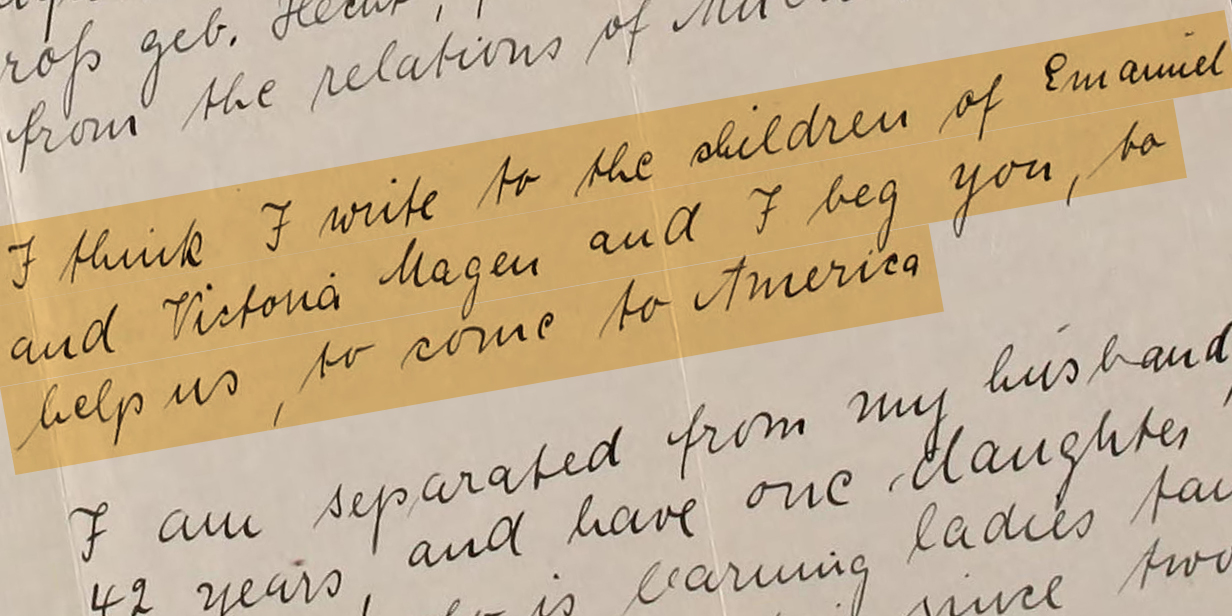

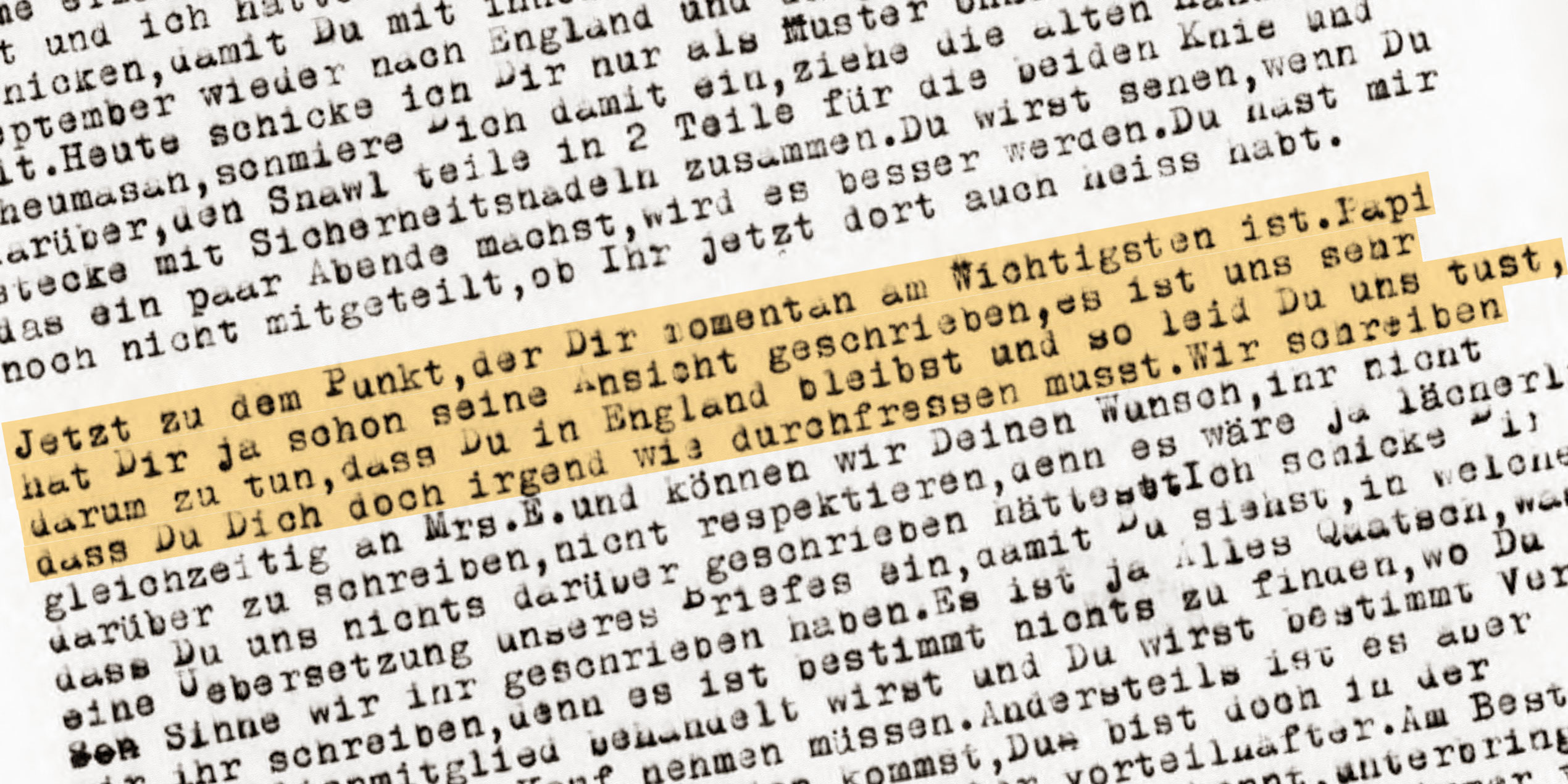

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency described the situation of Austrian refugees in Czechoslovakia with far-sightedness. If none of their precarious circumstances changed (work ban, impoverishment, missing prospects…) the situation could soon become “a psychological problem as well as an economic and political one.” The JTA estimated that in the middle of September 1938 there were more than 1,000 refugees in Czechoslovakia, most of them in Brno, less than 50 kilometers from the Austrian border. Now a police measure stipulated a bail of 2,000 Czech crowns (70 dollars) for persons who had already spent more than two months in Czechoslovakia. Otherwise they would face deportation. Who could pay this money on their behalf was completely unclear. Neither the Jewish community of Brno nor the League of Human Rights had the means to do so.

SOURCE

Institution:

Collection:

“500 Refugees Face Expulsion from Czechoslovakia”

Source available in English