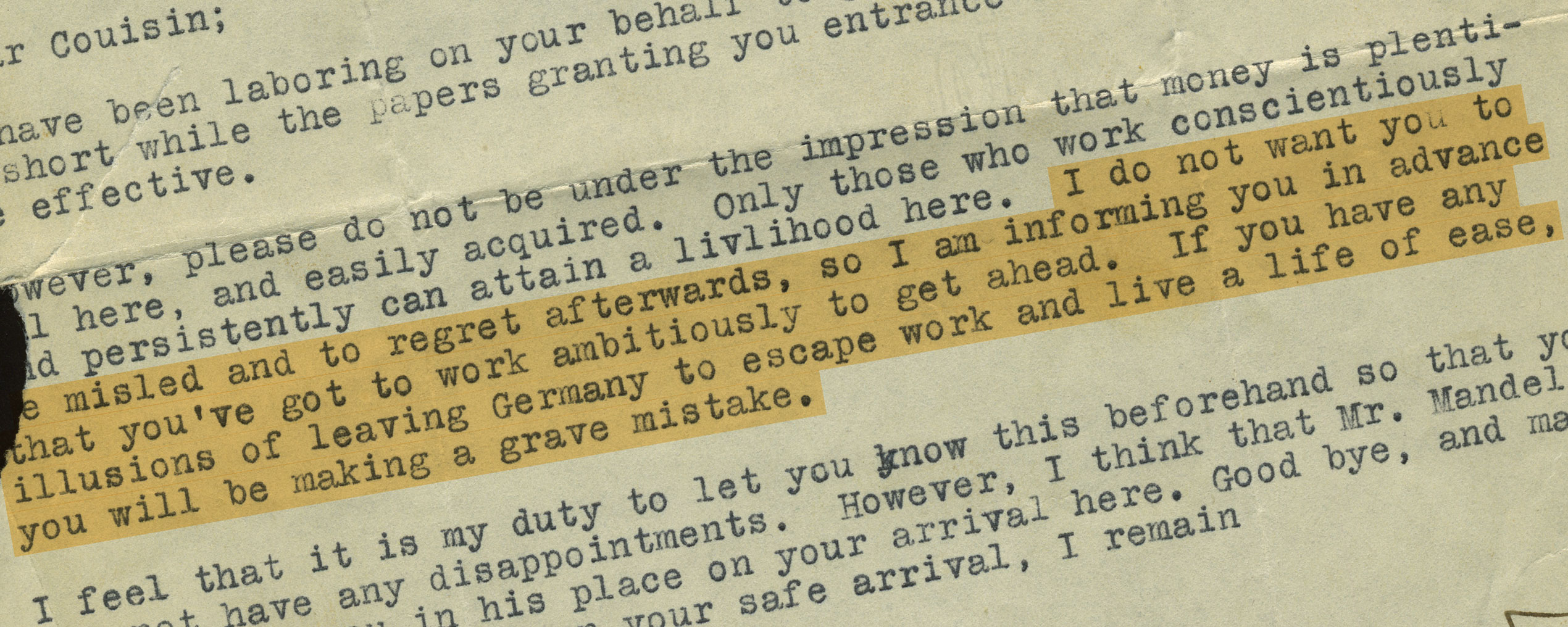

An inappropriate insinuation

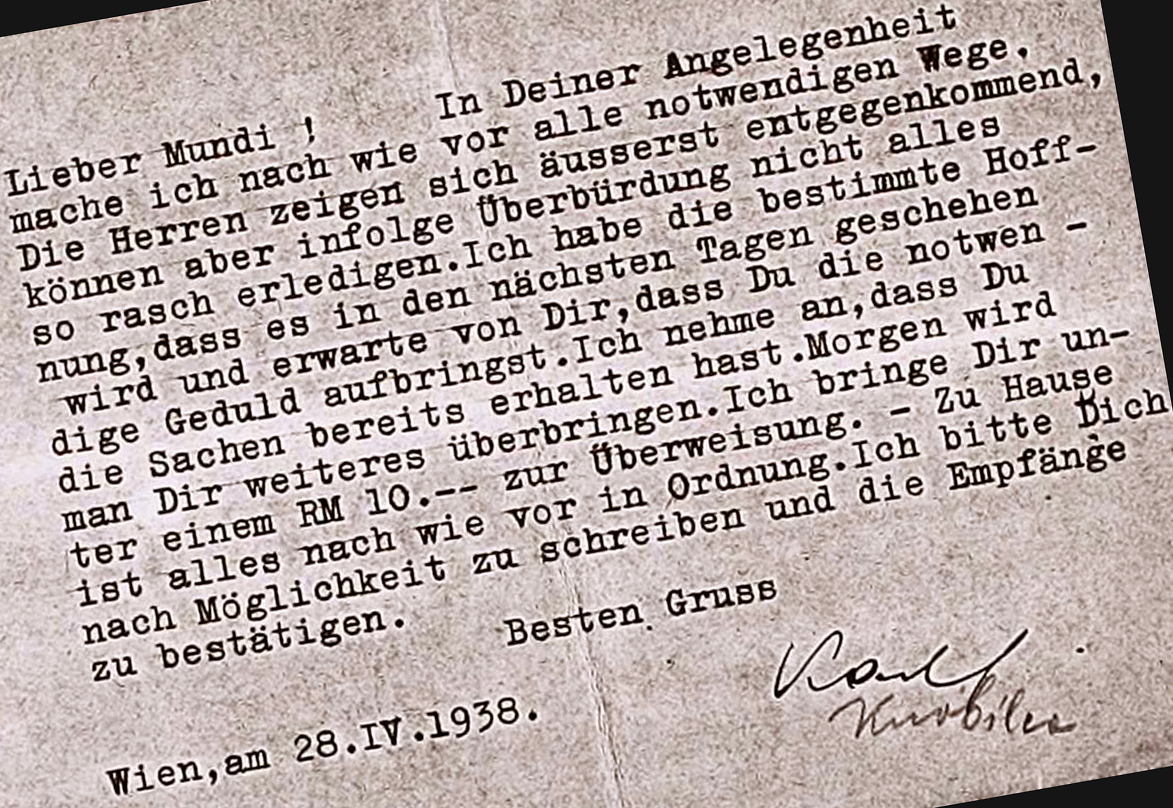

An American warns his Viennese cousin against coming to America to loaf

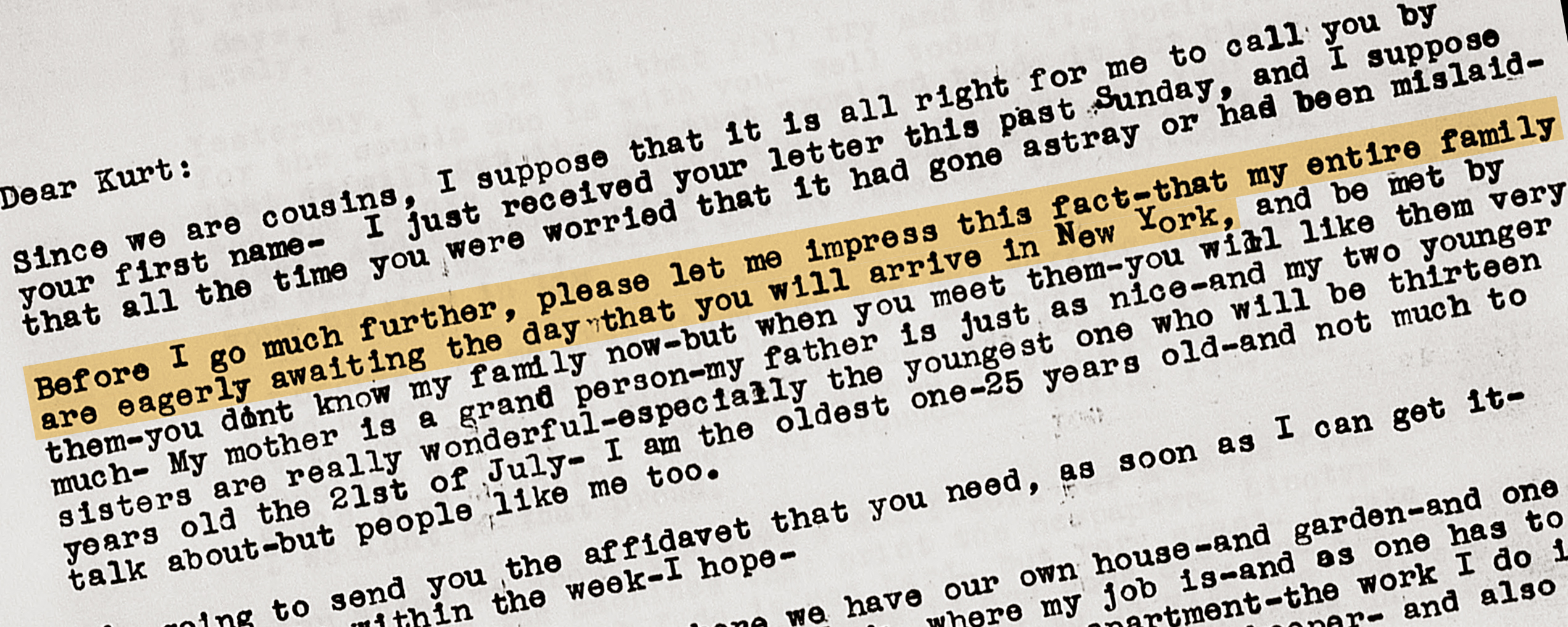

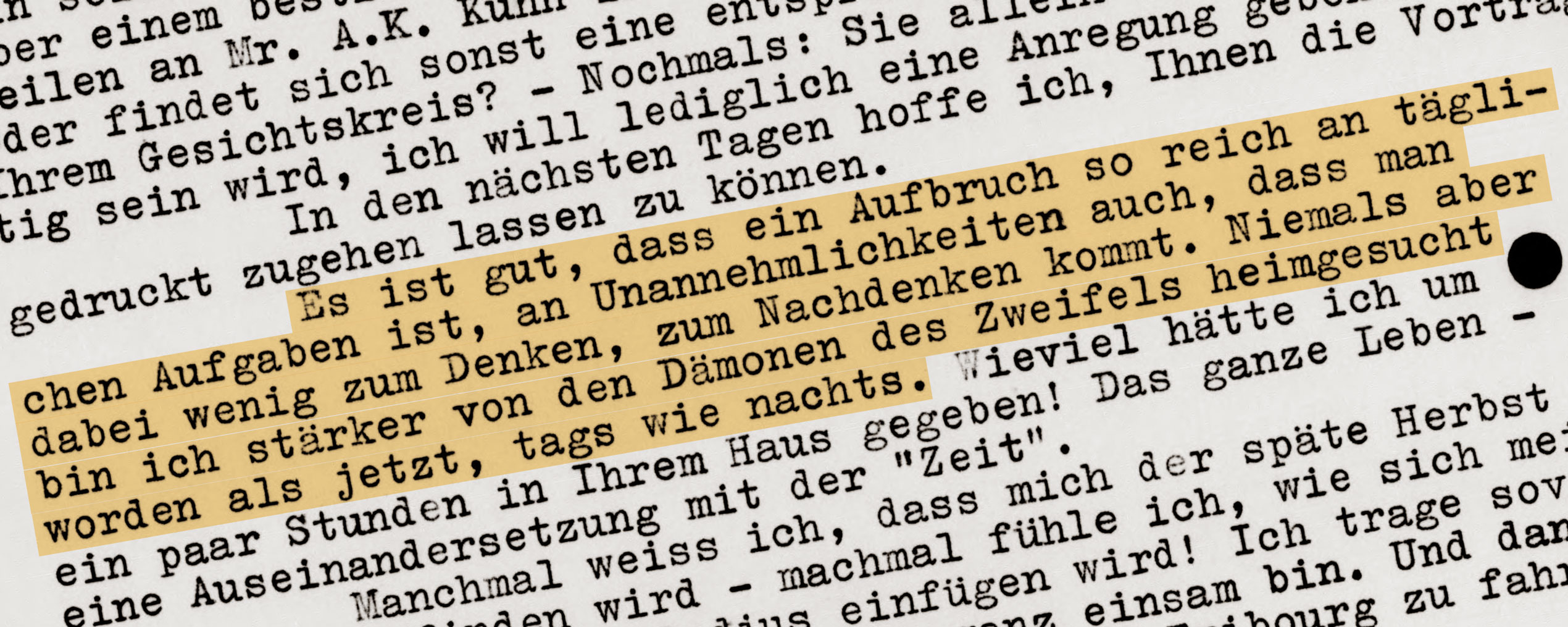

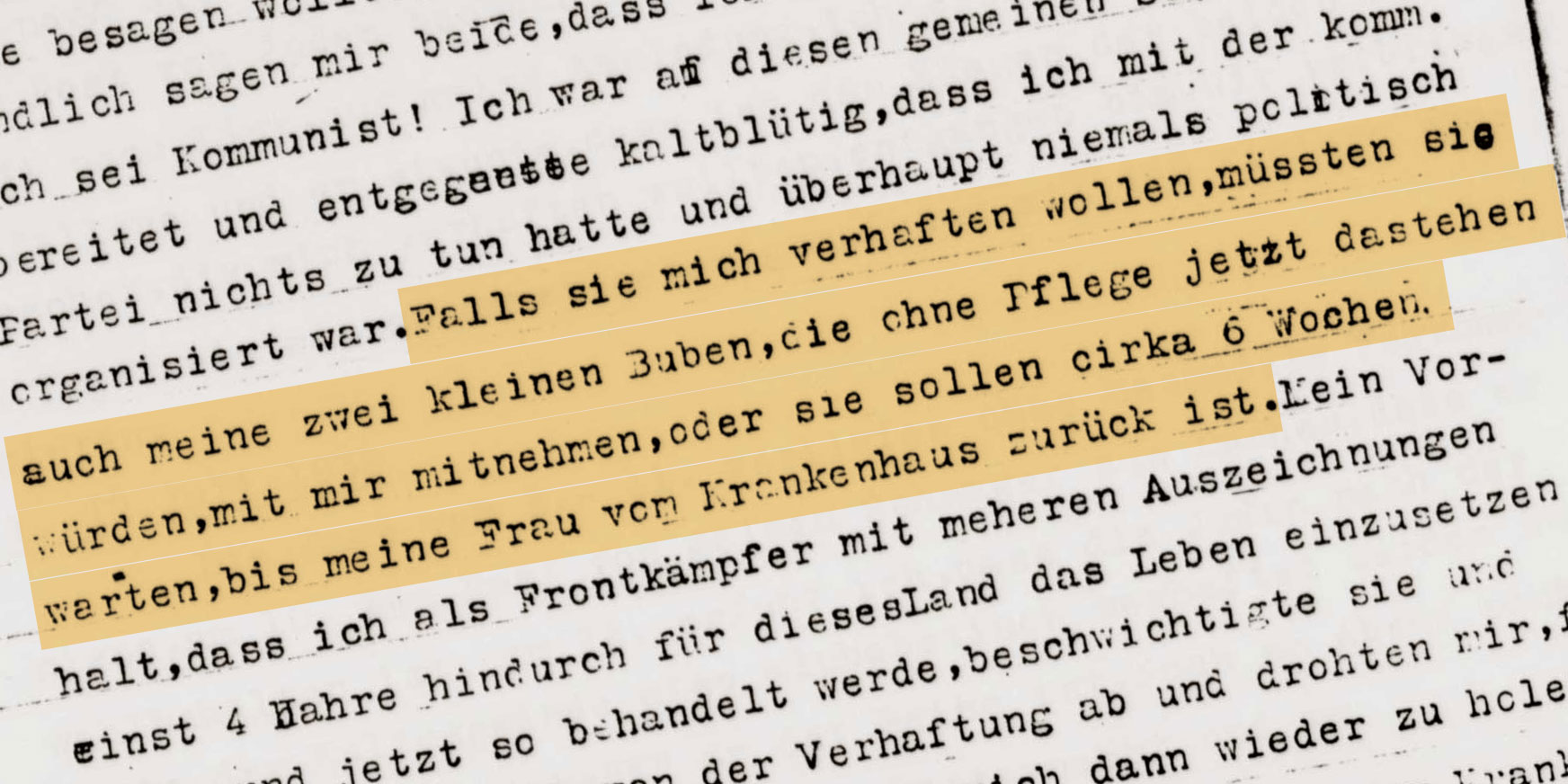

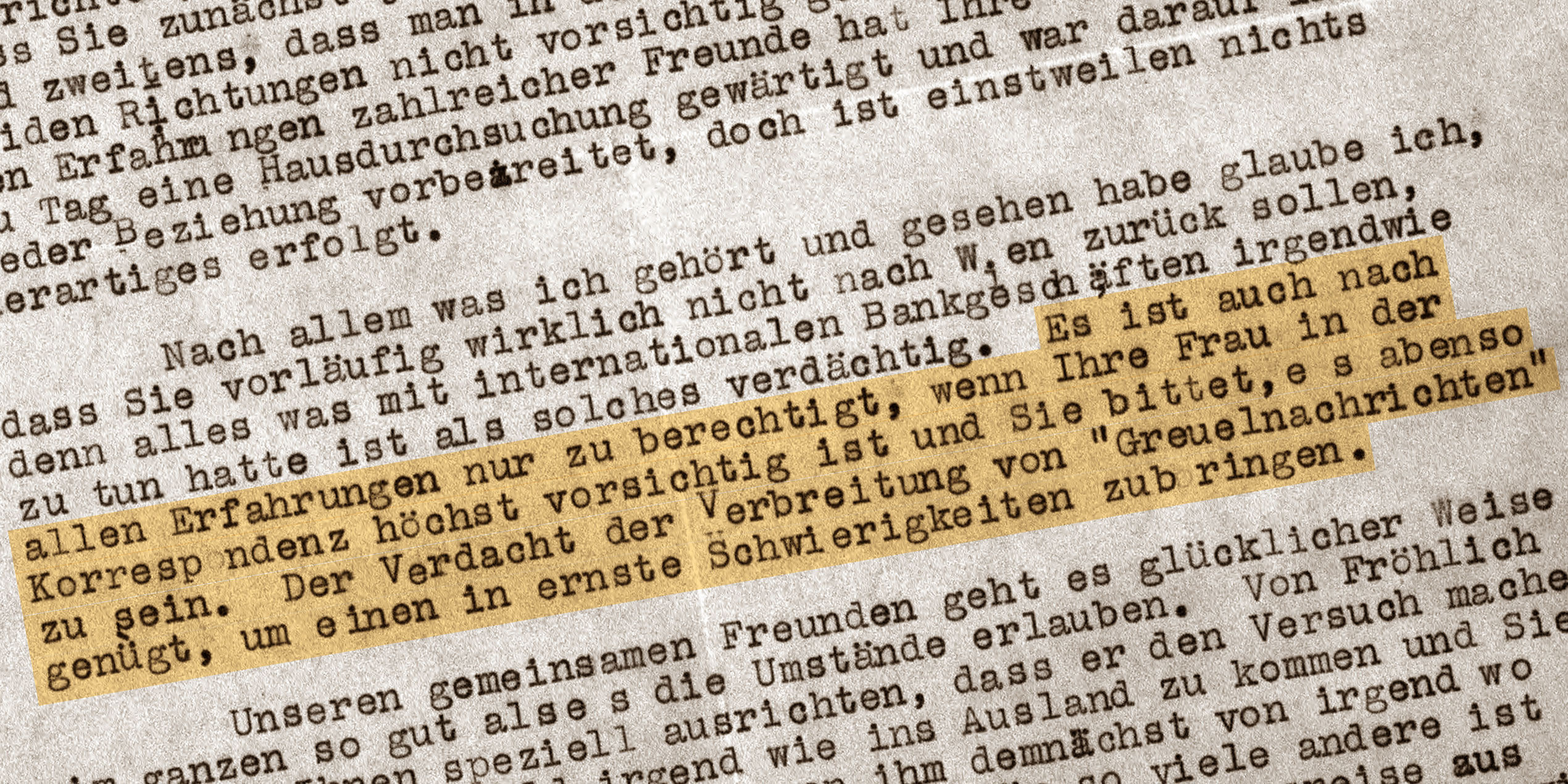

“I do not want you to be misled and to feel regret afterwards, so I am informing you in advance that you've got to work ambitiously to get ahead. If you have any illusions of leaving Germany to escape work and live a life of ease, you will be making a grave mistake.”

New York/Vienna

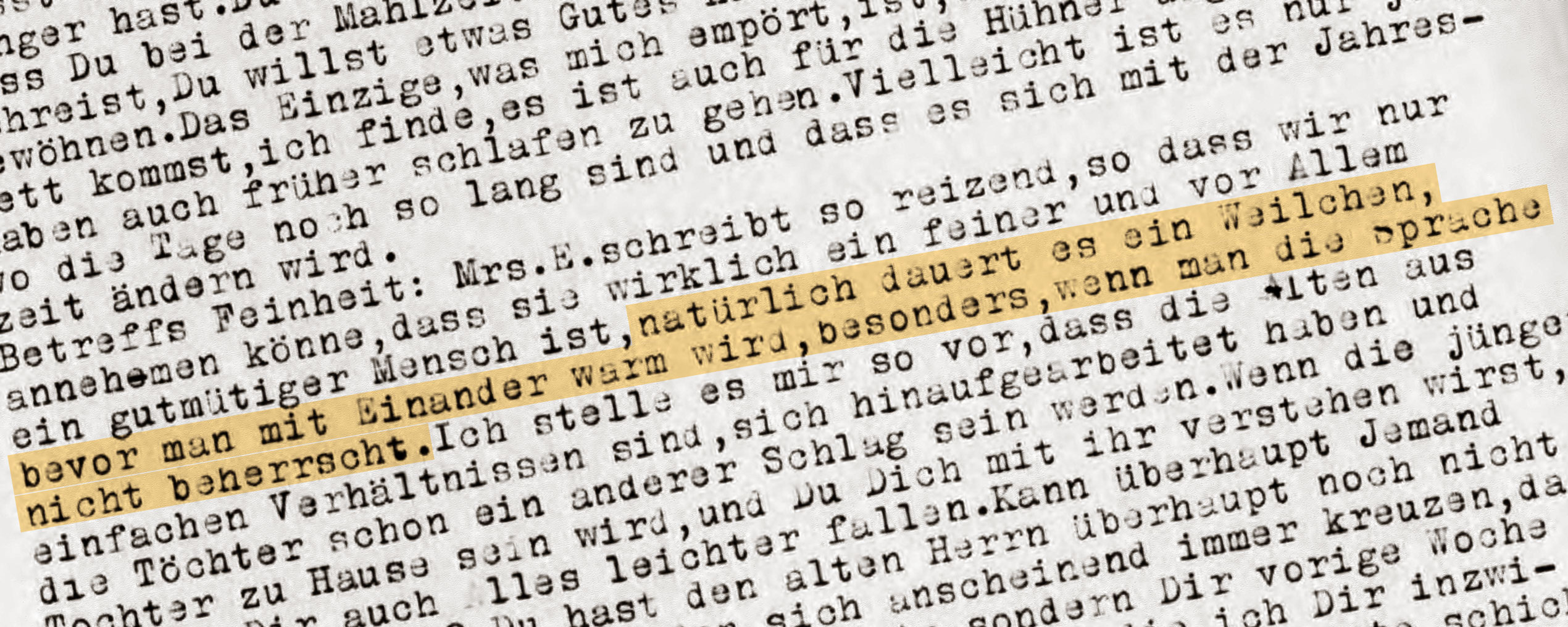

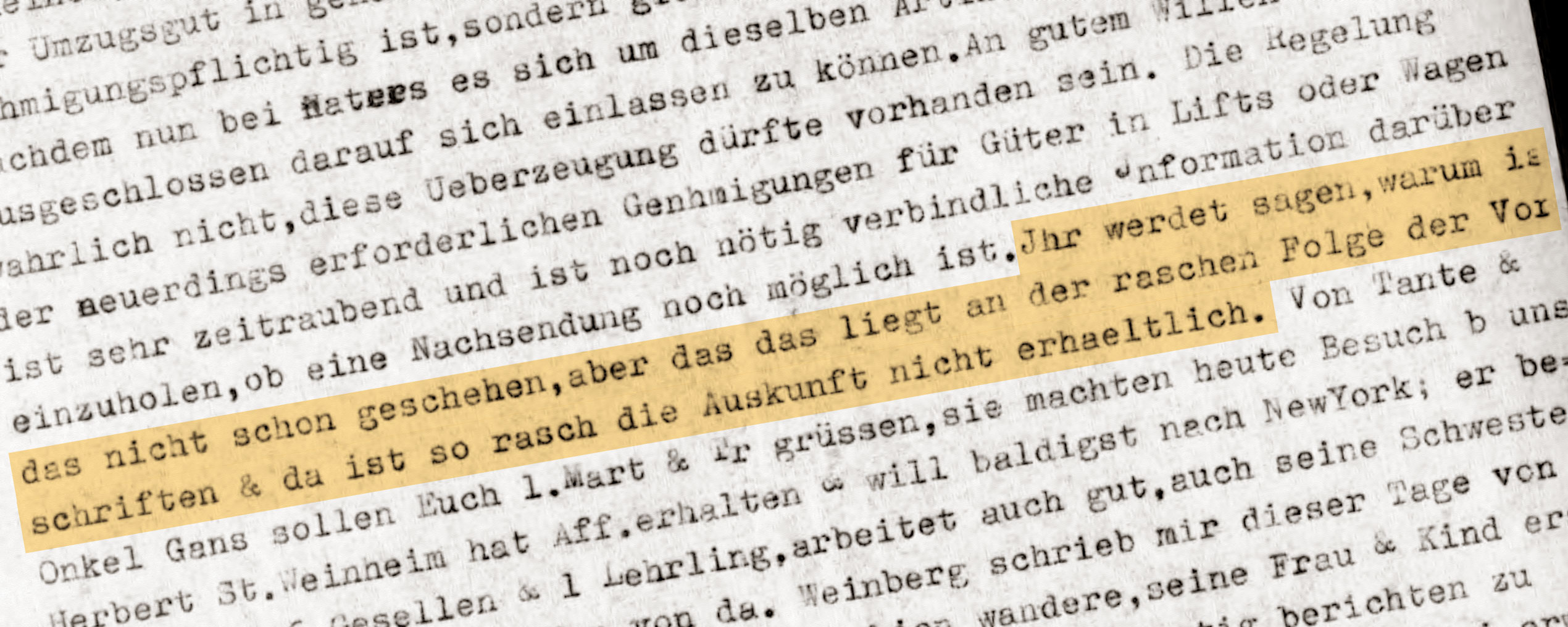

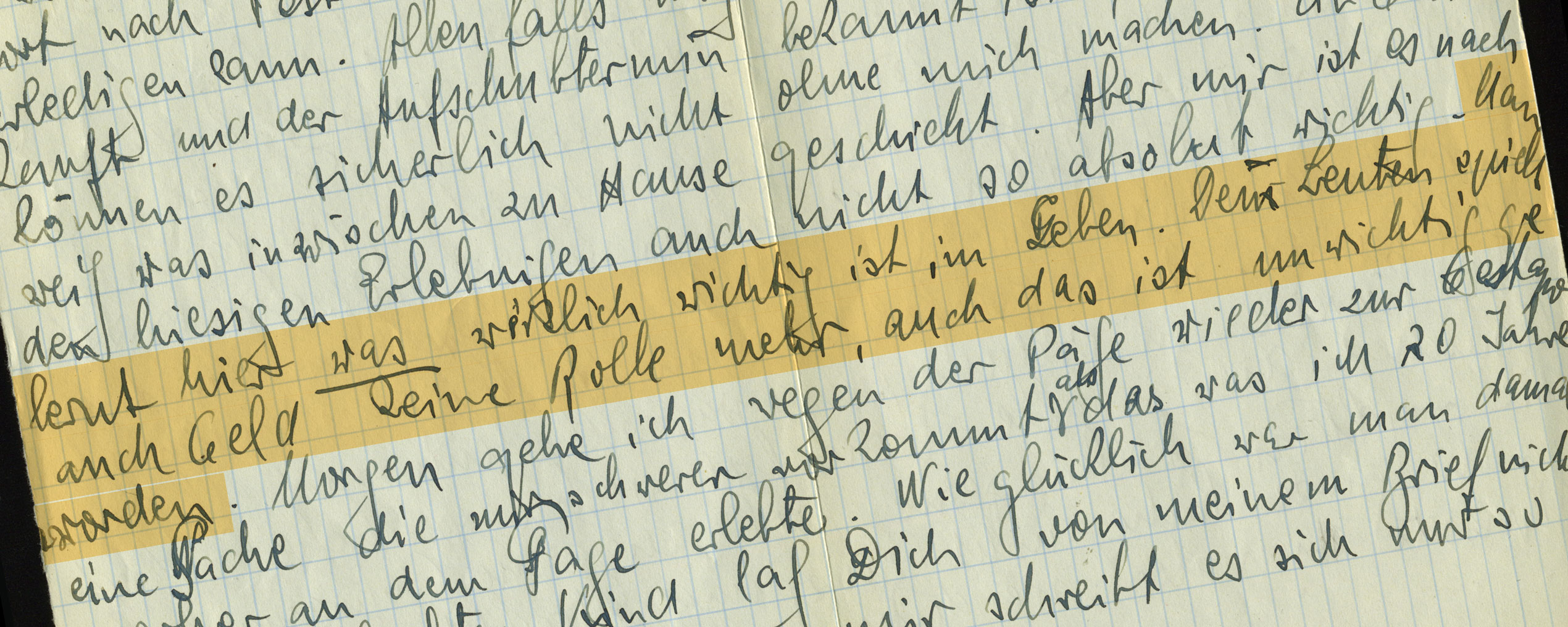

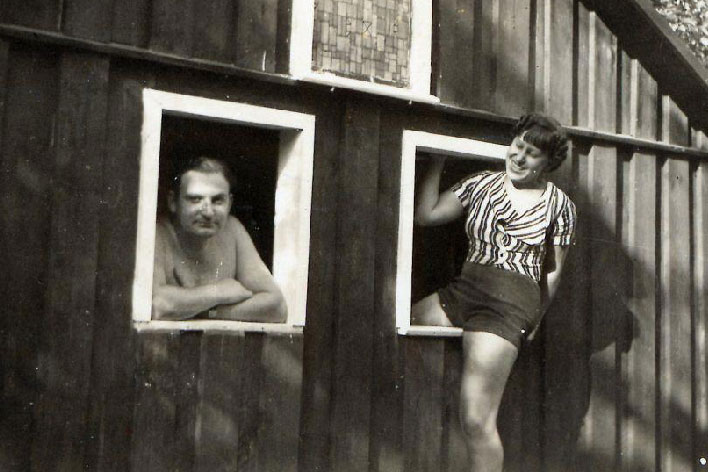

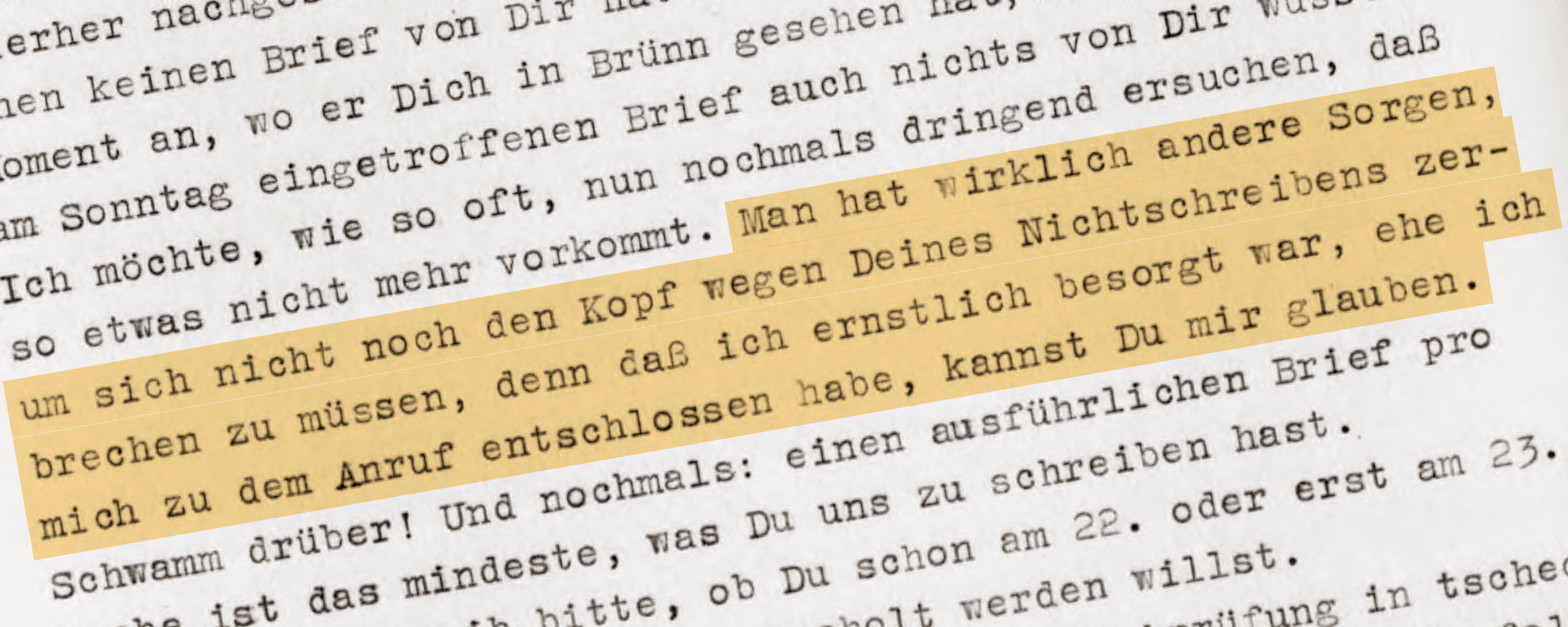

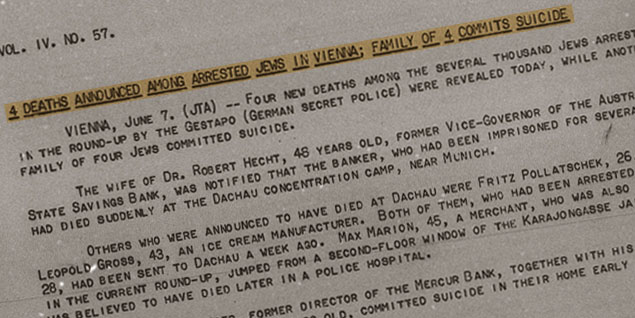

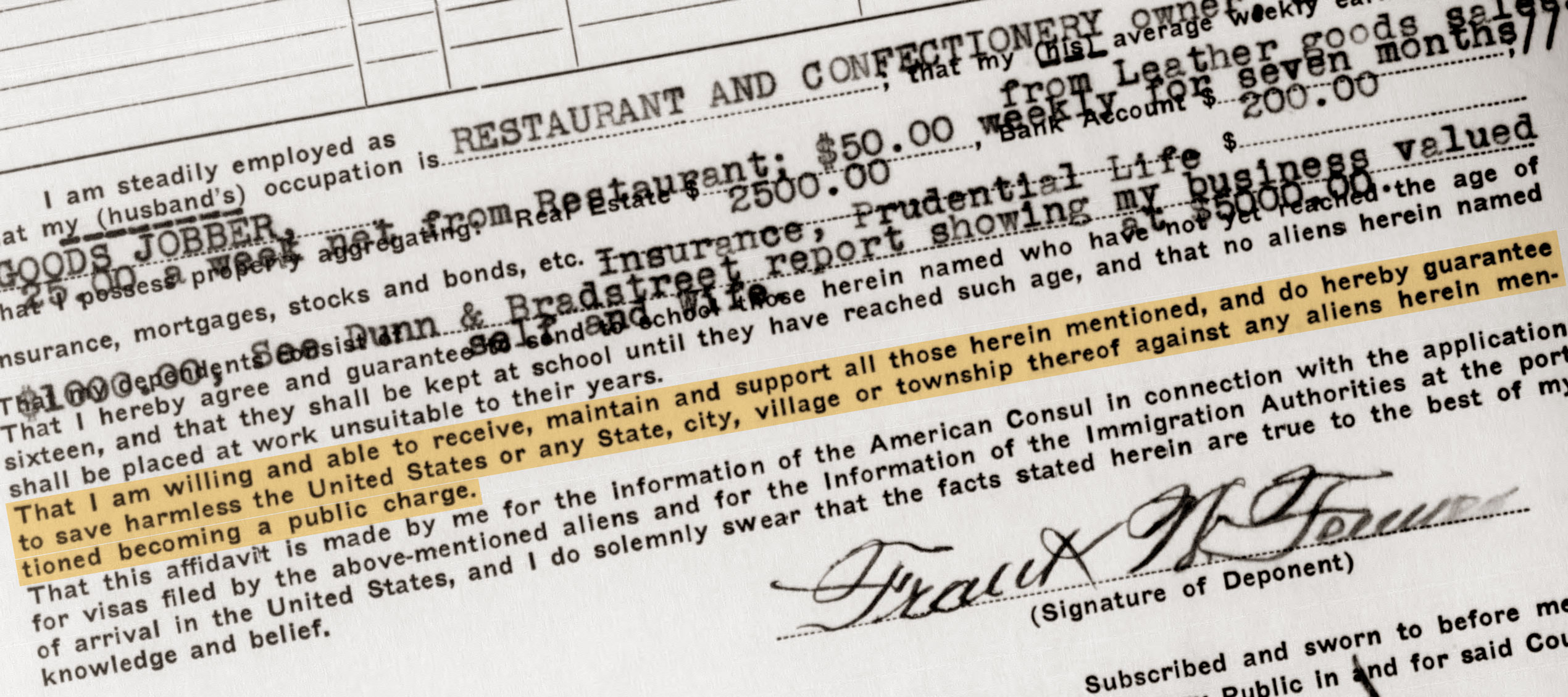

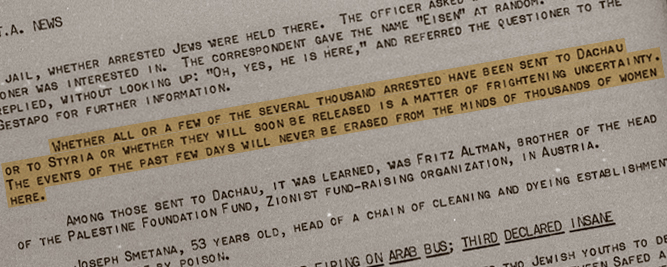

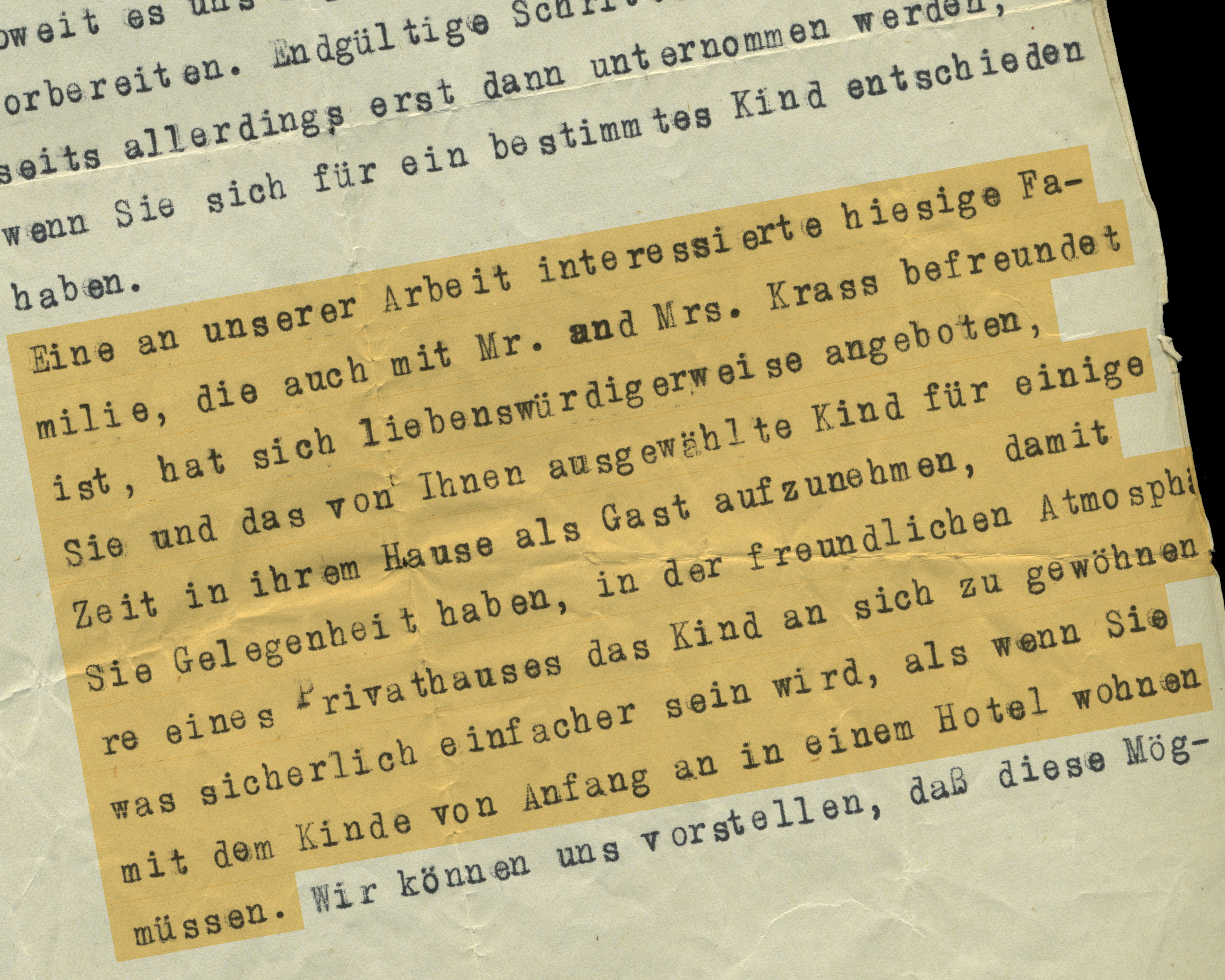

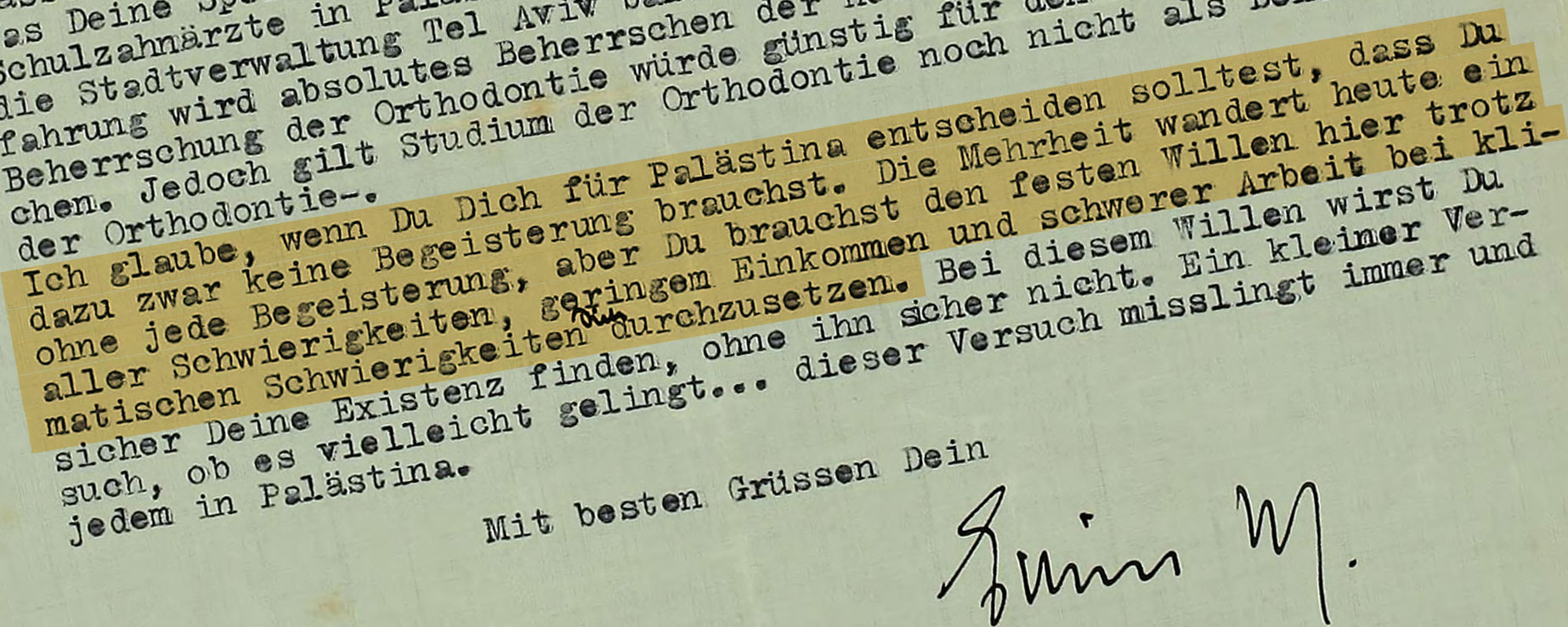

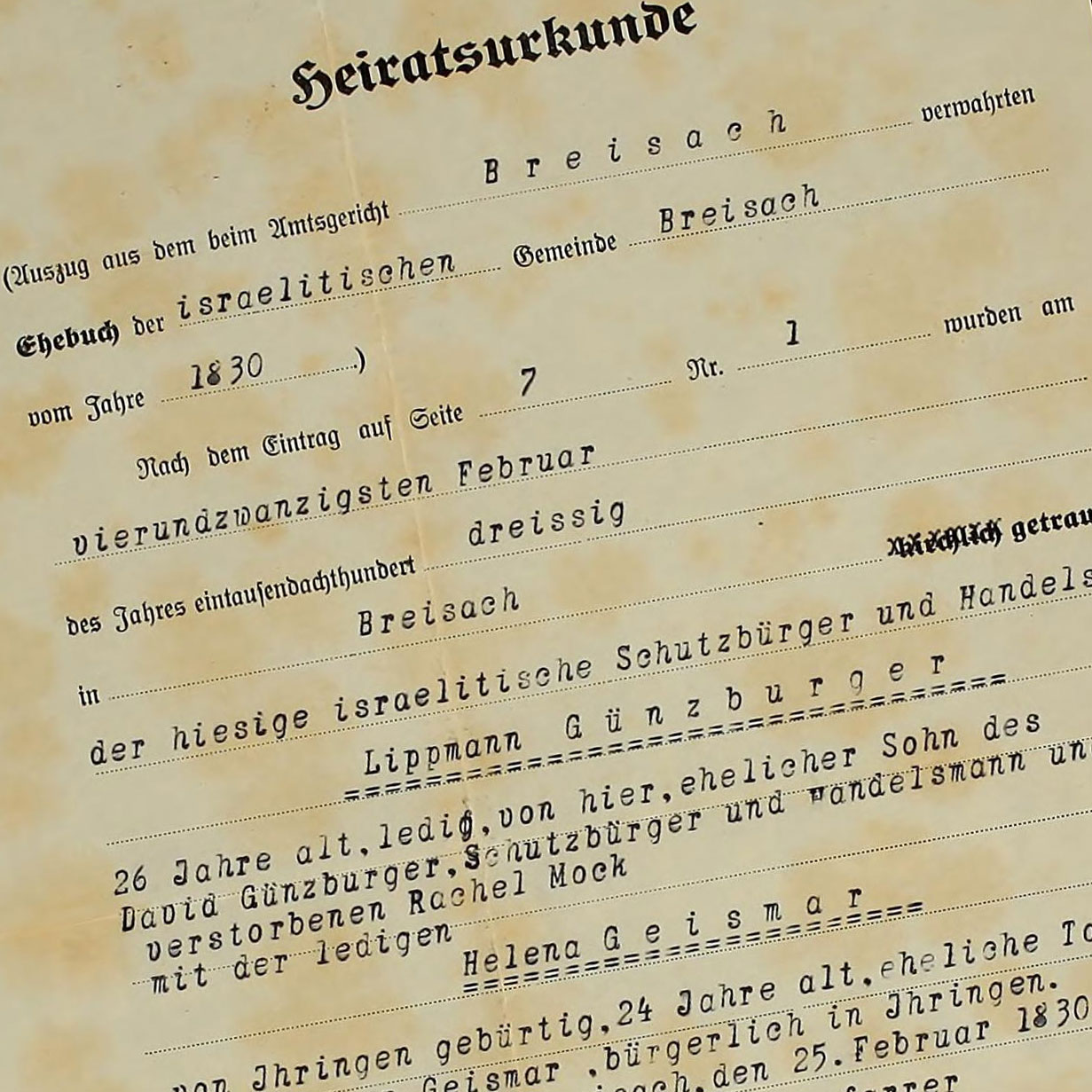

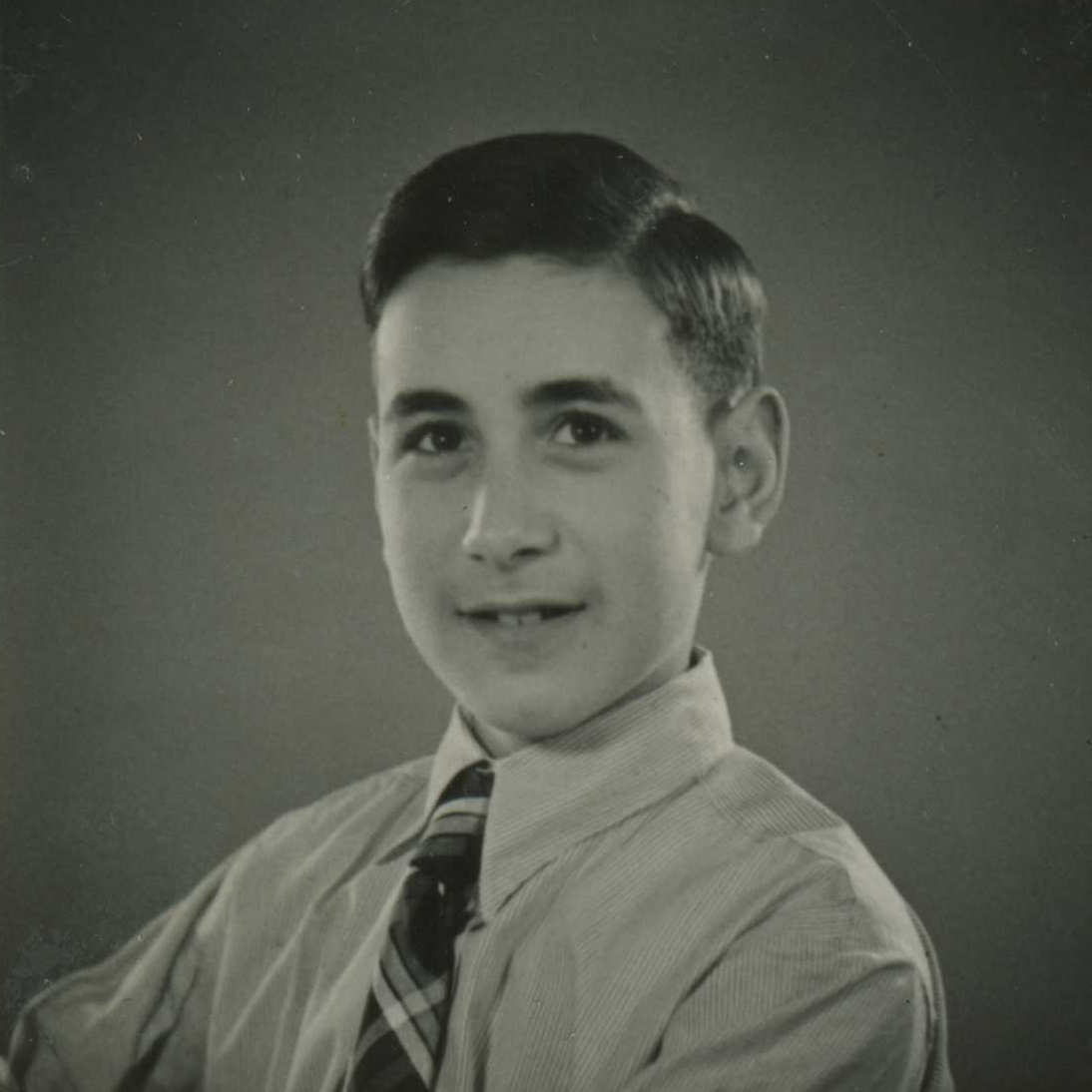

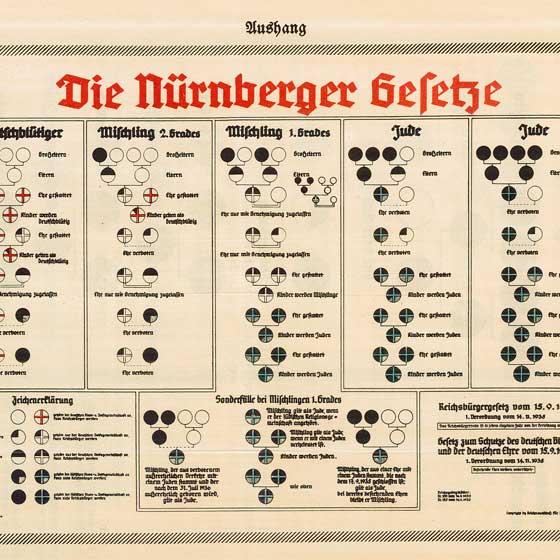

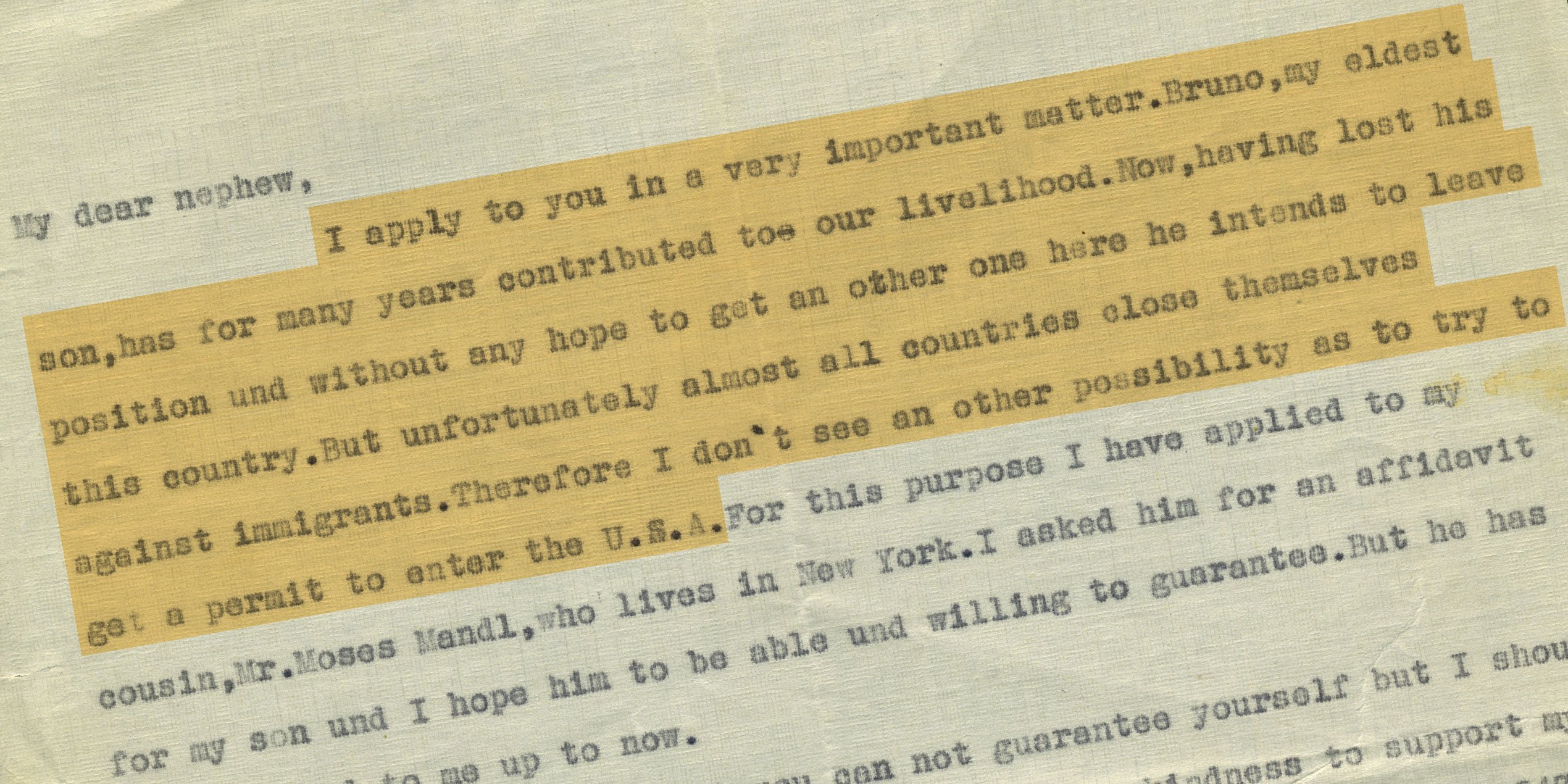

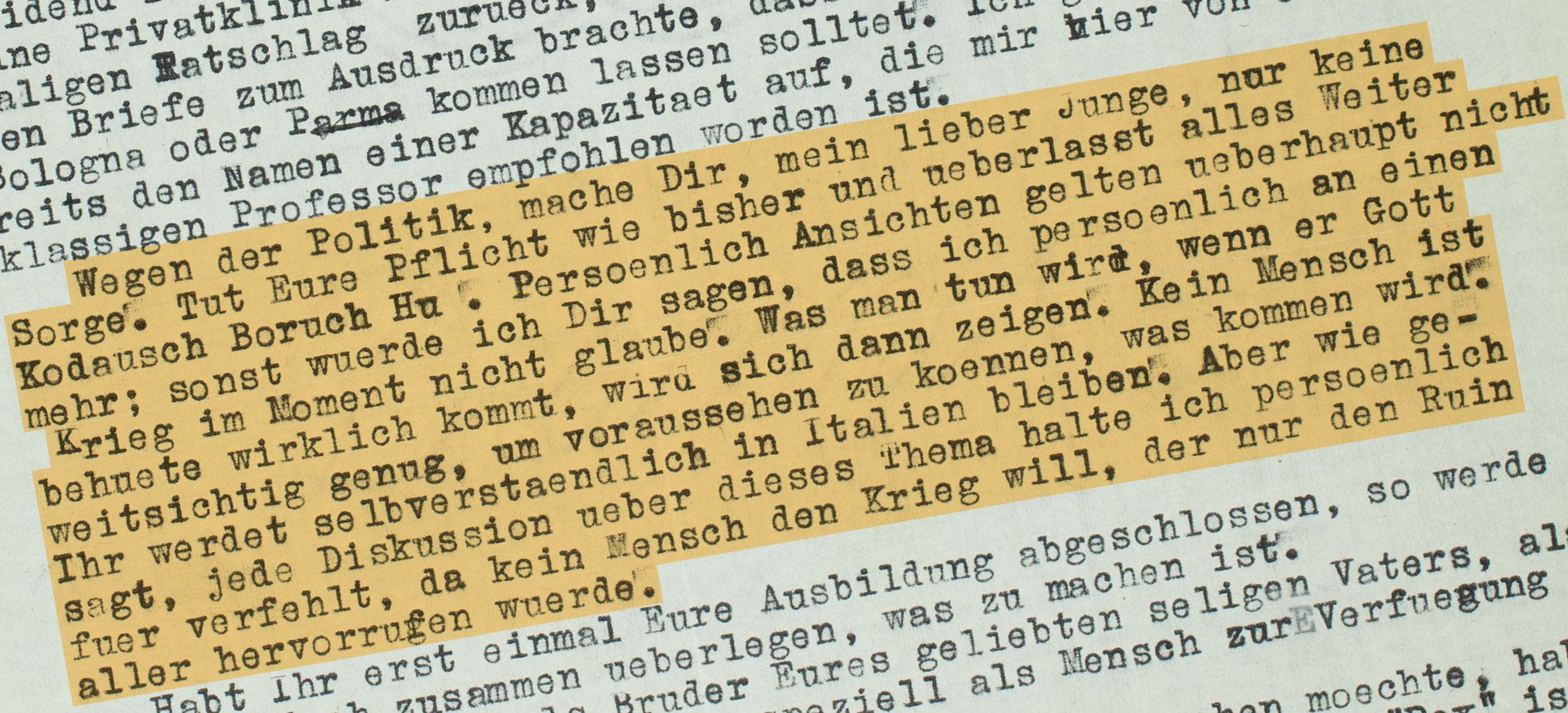

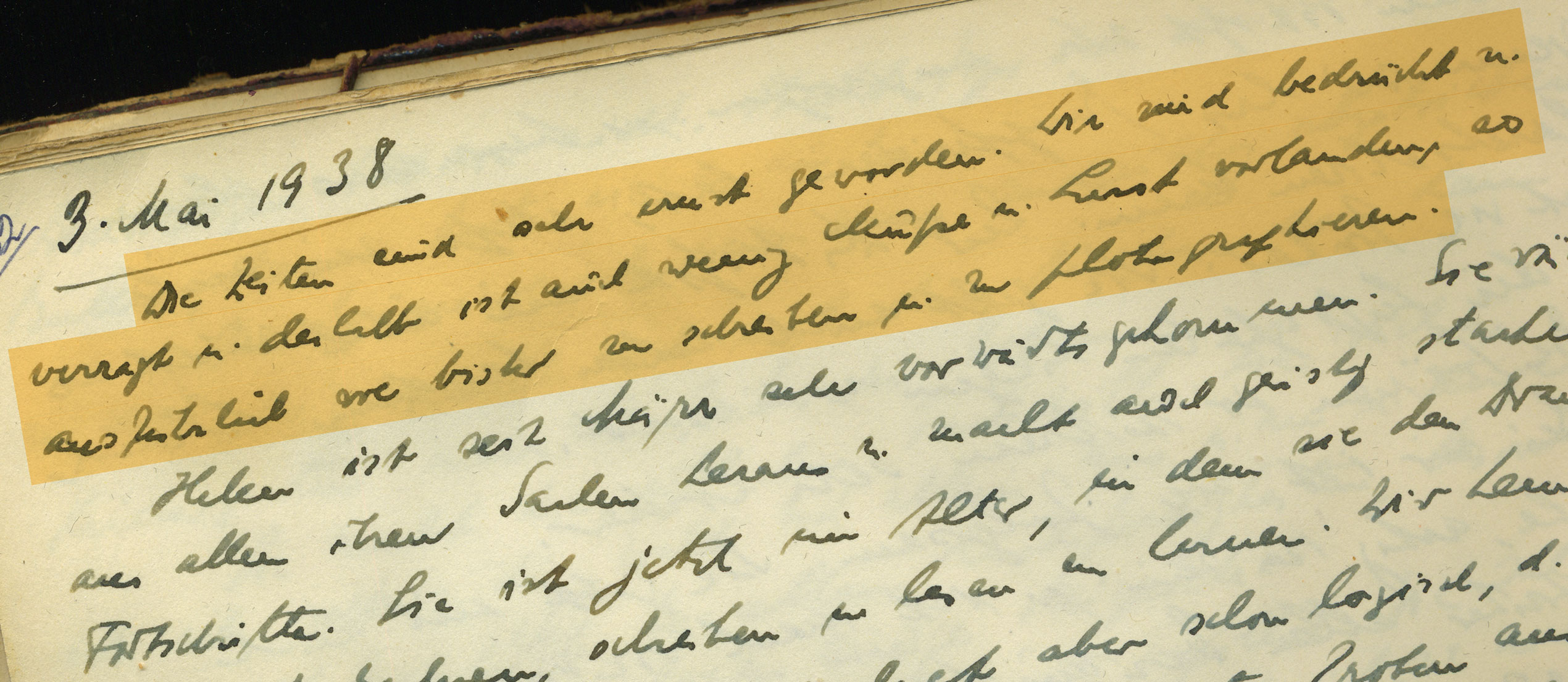

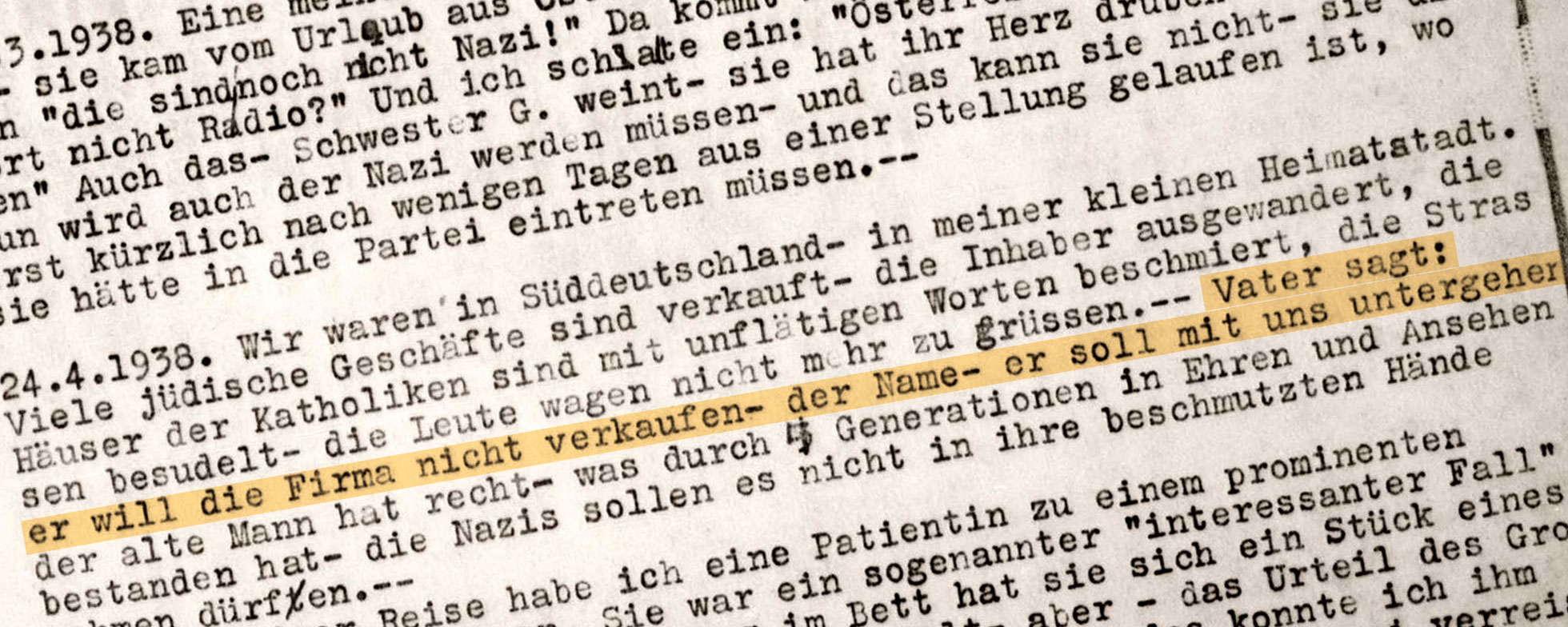

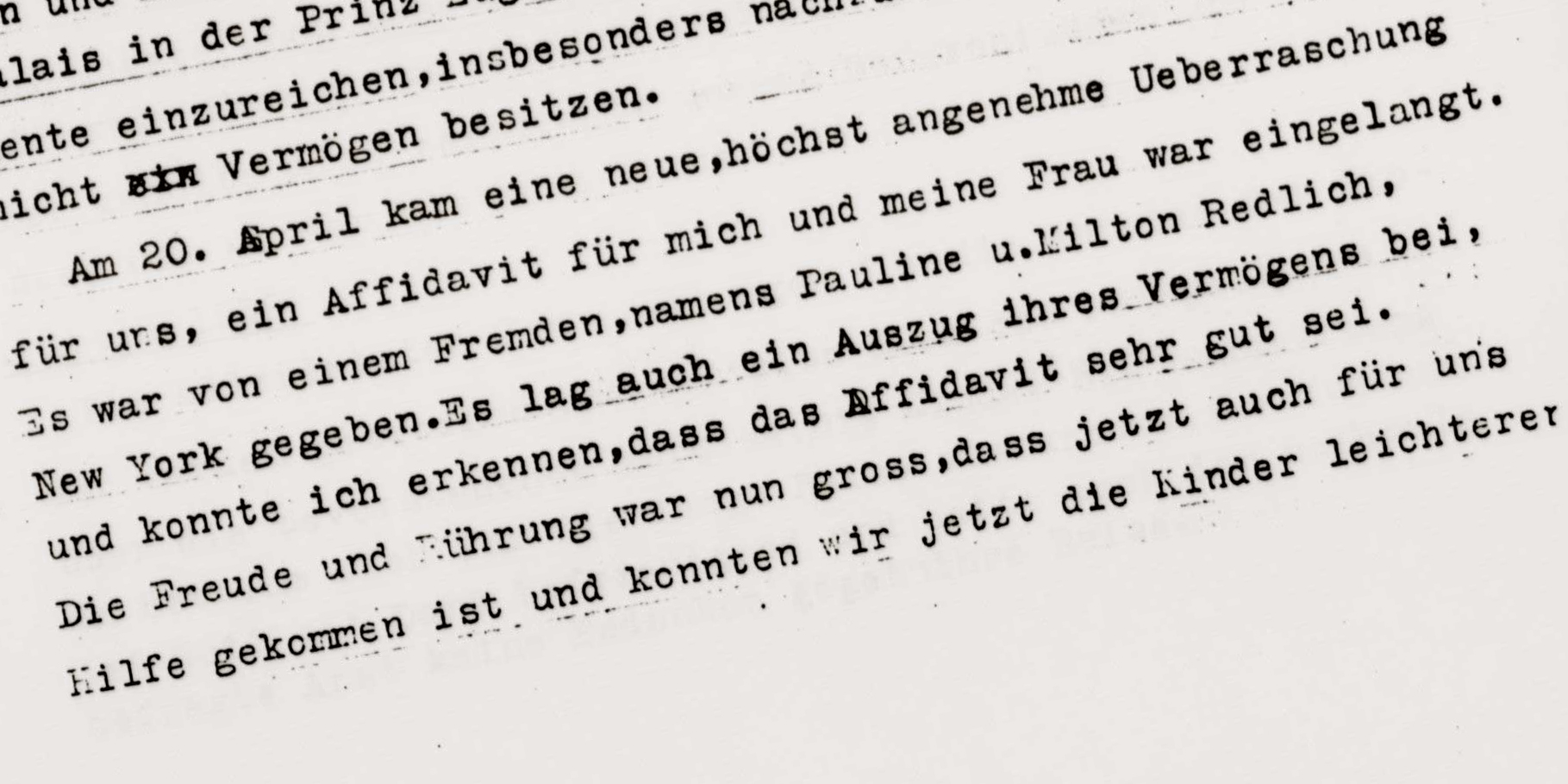

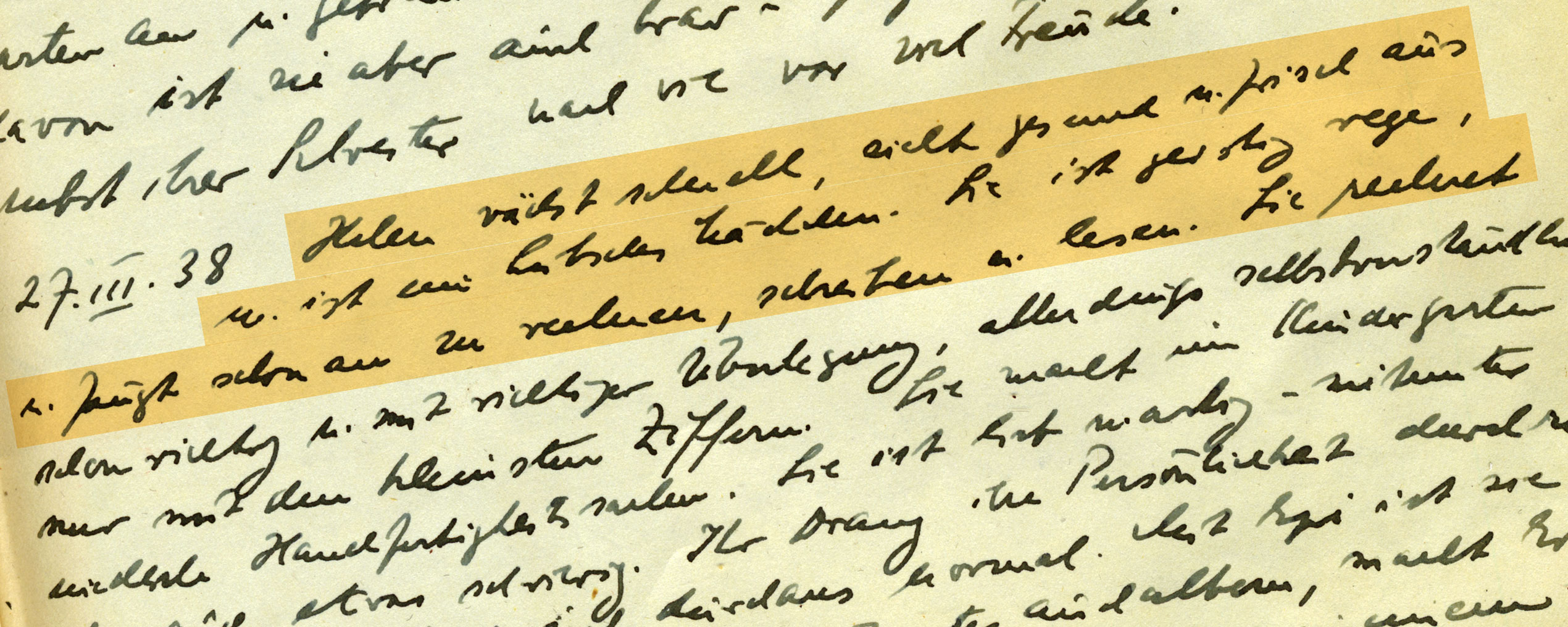

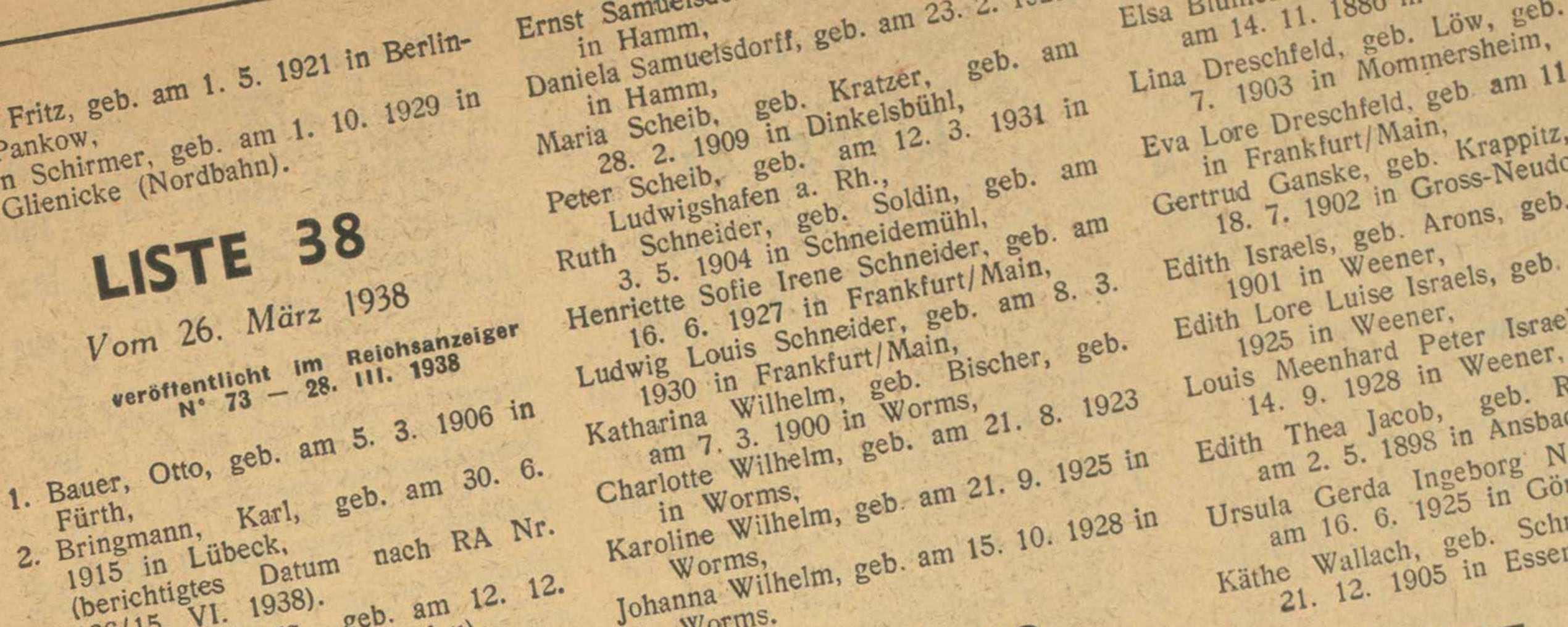

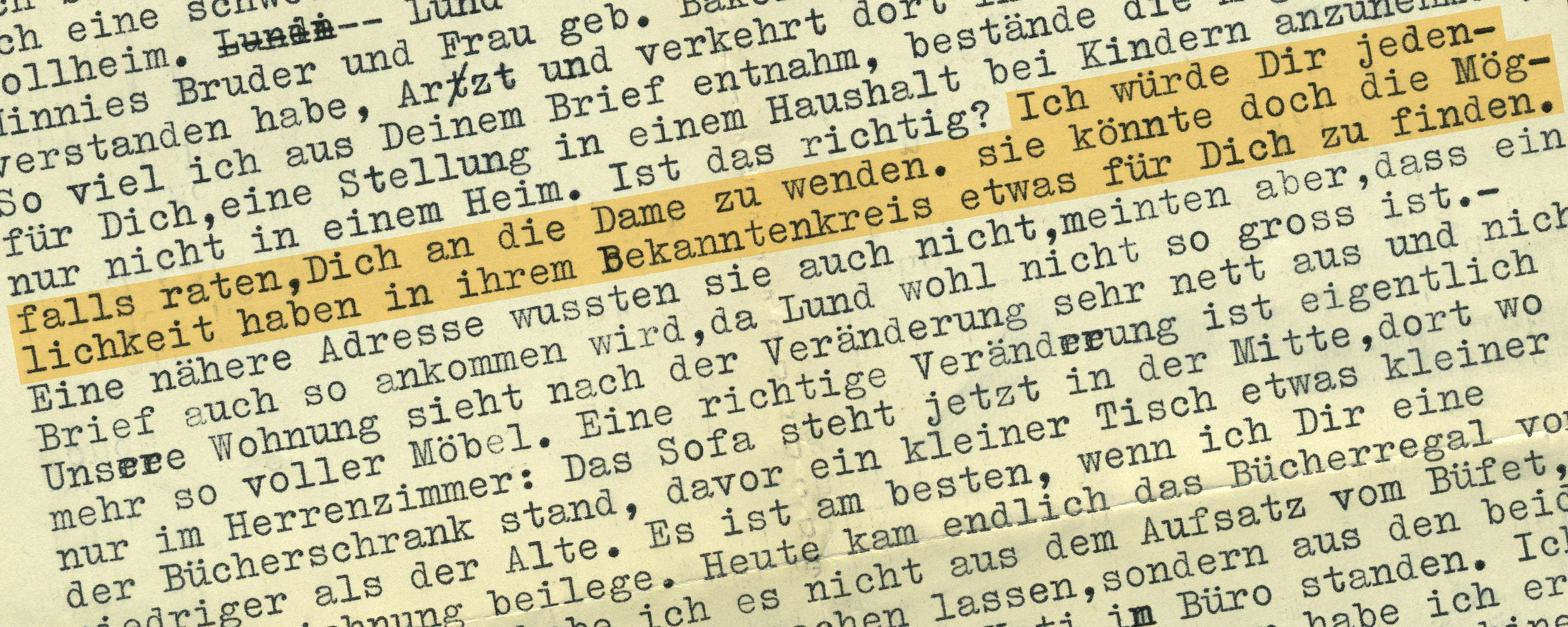

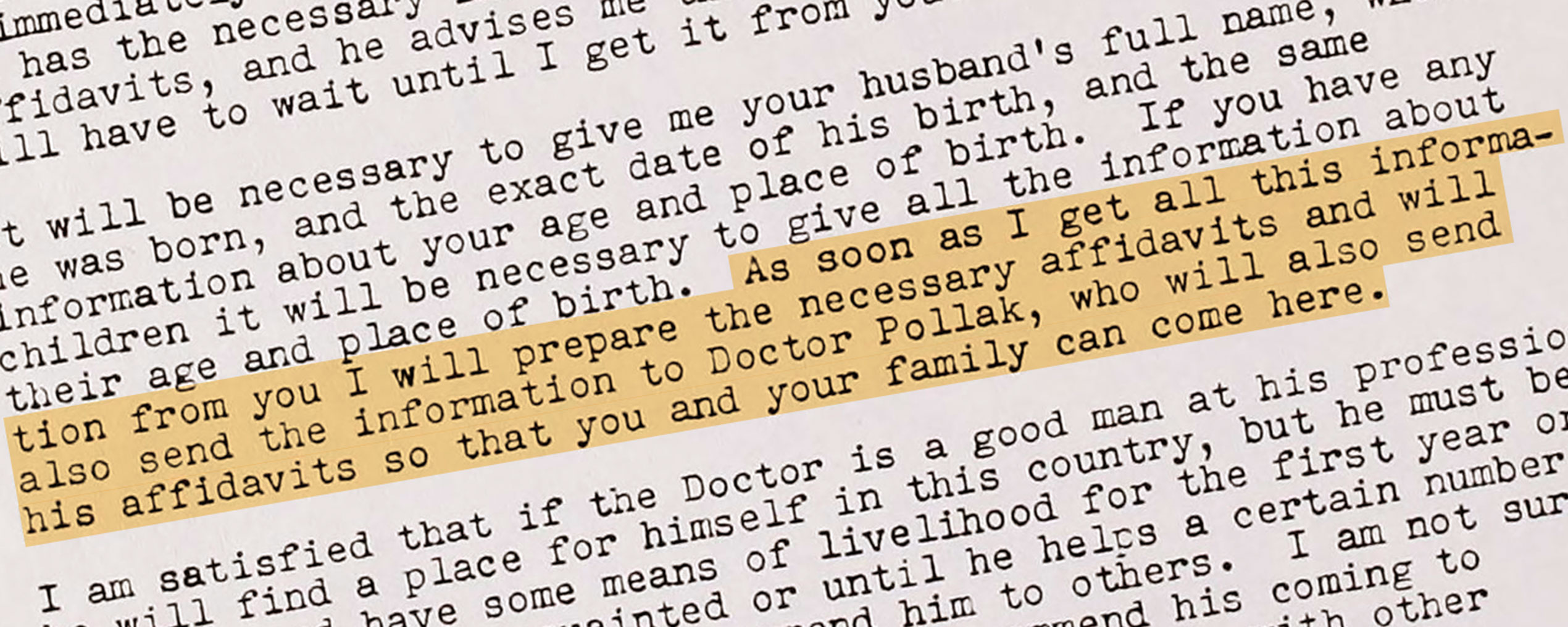

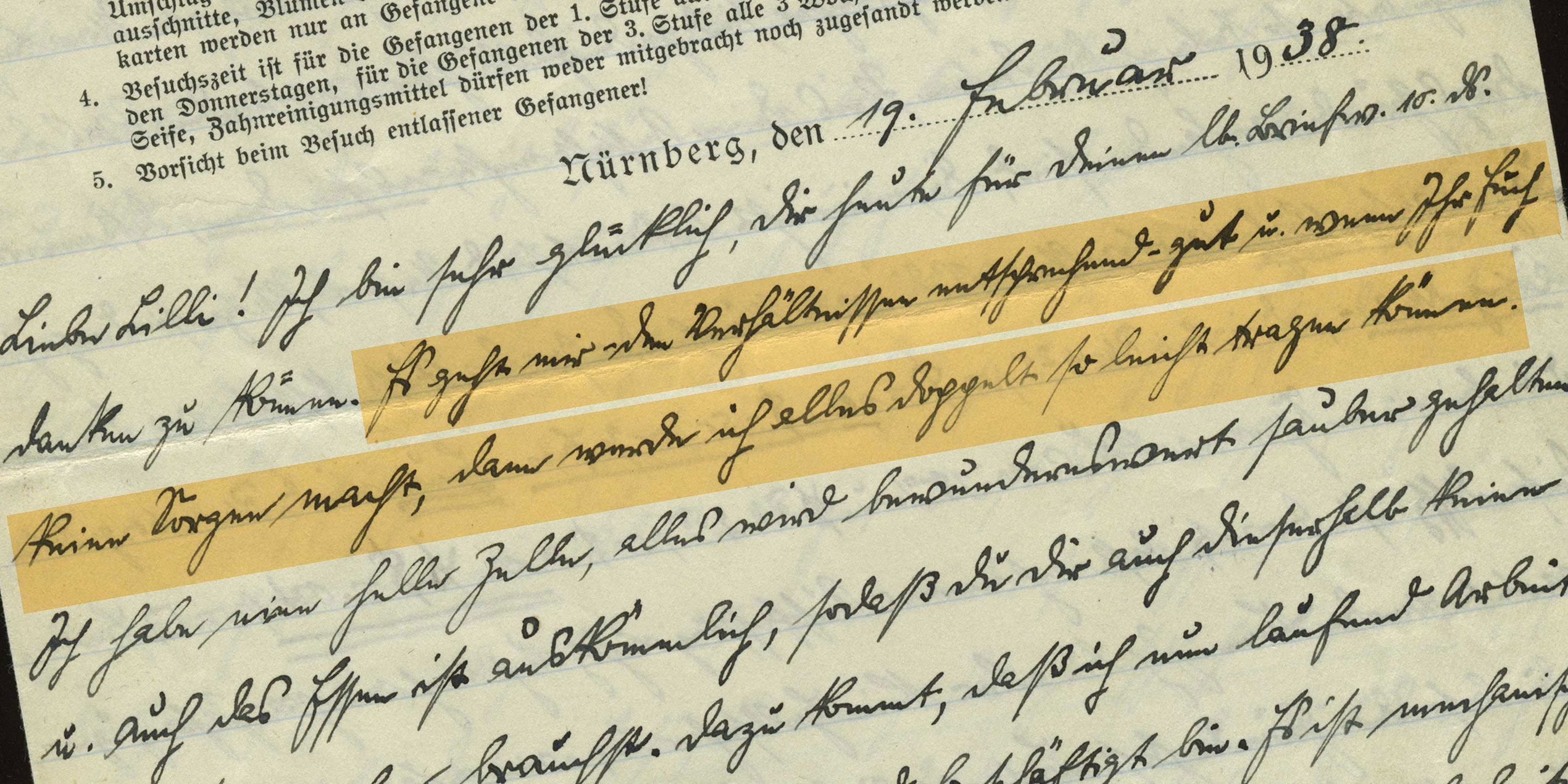

In May 1938, Betty Blum had contacted her nephew Stanley Frankfurt in New York. Her son Bruno had lost his position in Vienna, and it was unlikely that he would find other employment. She did not elaborate on the situation of Austria’s Jews in general since the country’s annexation by Nazi Germany but wondered whether Stanley could do something for Bruno. When Bruno received Stanley’s July 16 letter, he must have been both relieved and taken aback. While assuring him that he had been active on his behalf doing the paperwork necessary to prepare for his immigration to the US, his cousin in New York also saw fit to point out to him that if his intention was coming to America for the purpose of “living a life of ease,” he was on the wrong track. Was Stanley really so uninformed about the plight of Austrian Jewry under the new authorities? It can be assumed that his sincere efforts on his Austrian cousin’s behalf made up for the bafflement that must have been caused by his inappropriate insinuation.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Blum Family Collection, AR 25132

Original:

Box 1, folder 5

Source available in English