Homesick

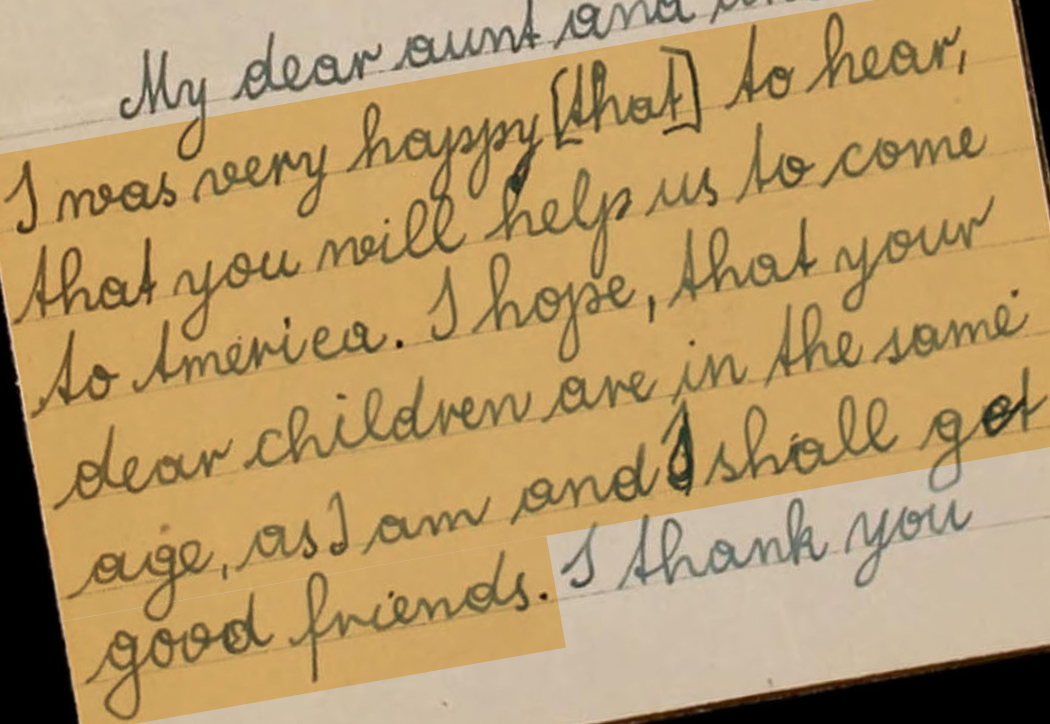

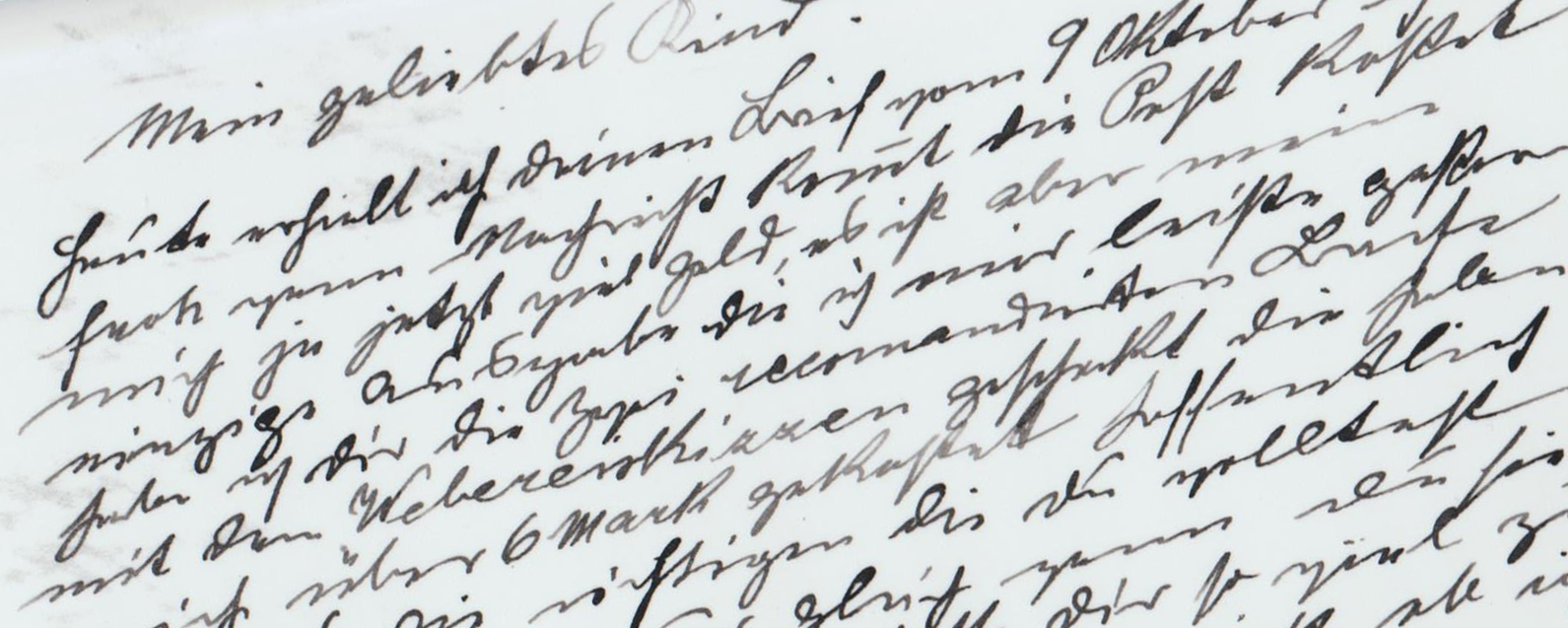

First letter to a child emigrant

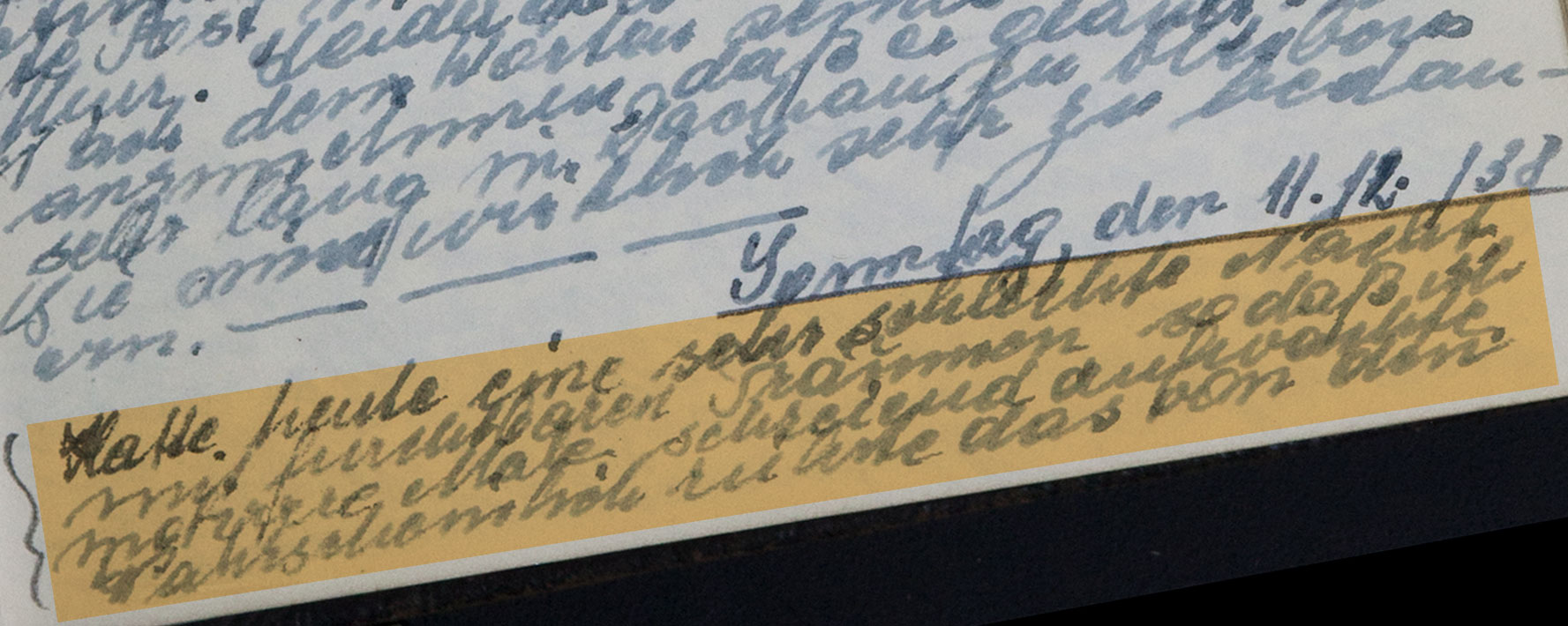

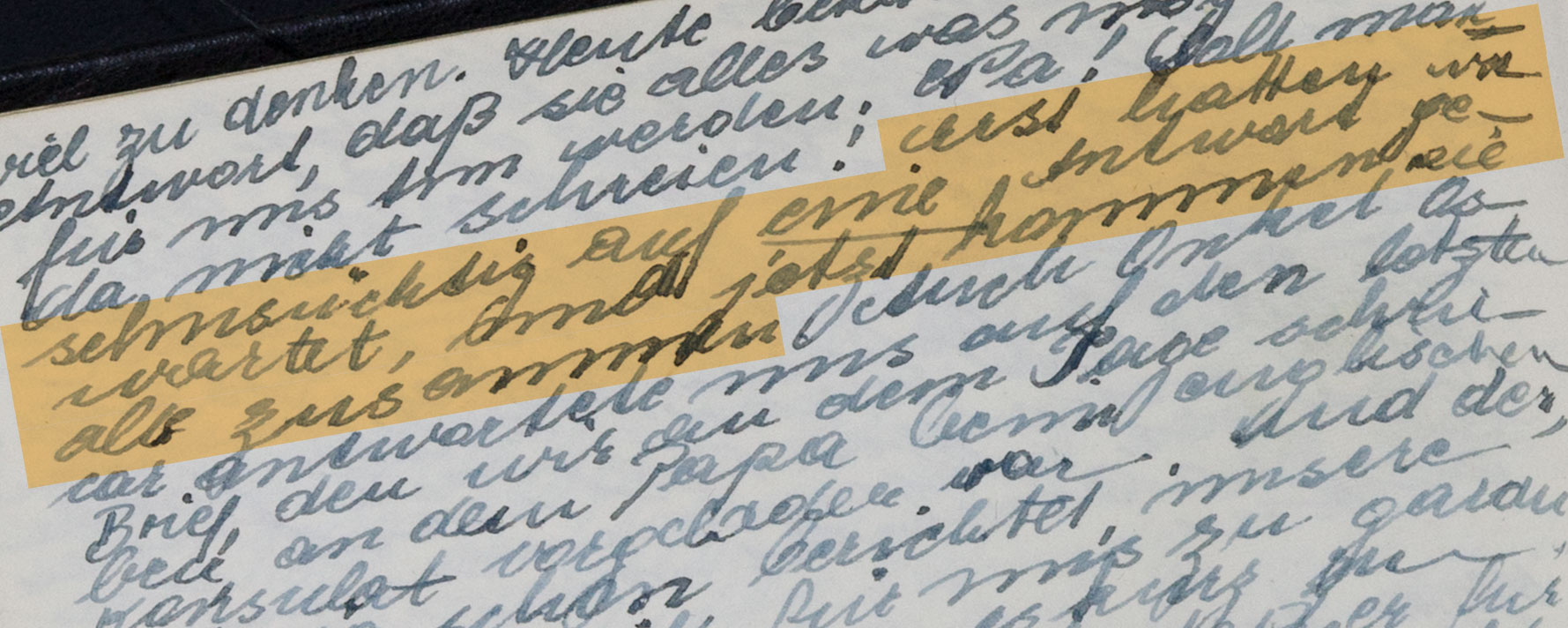

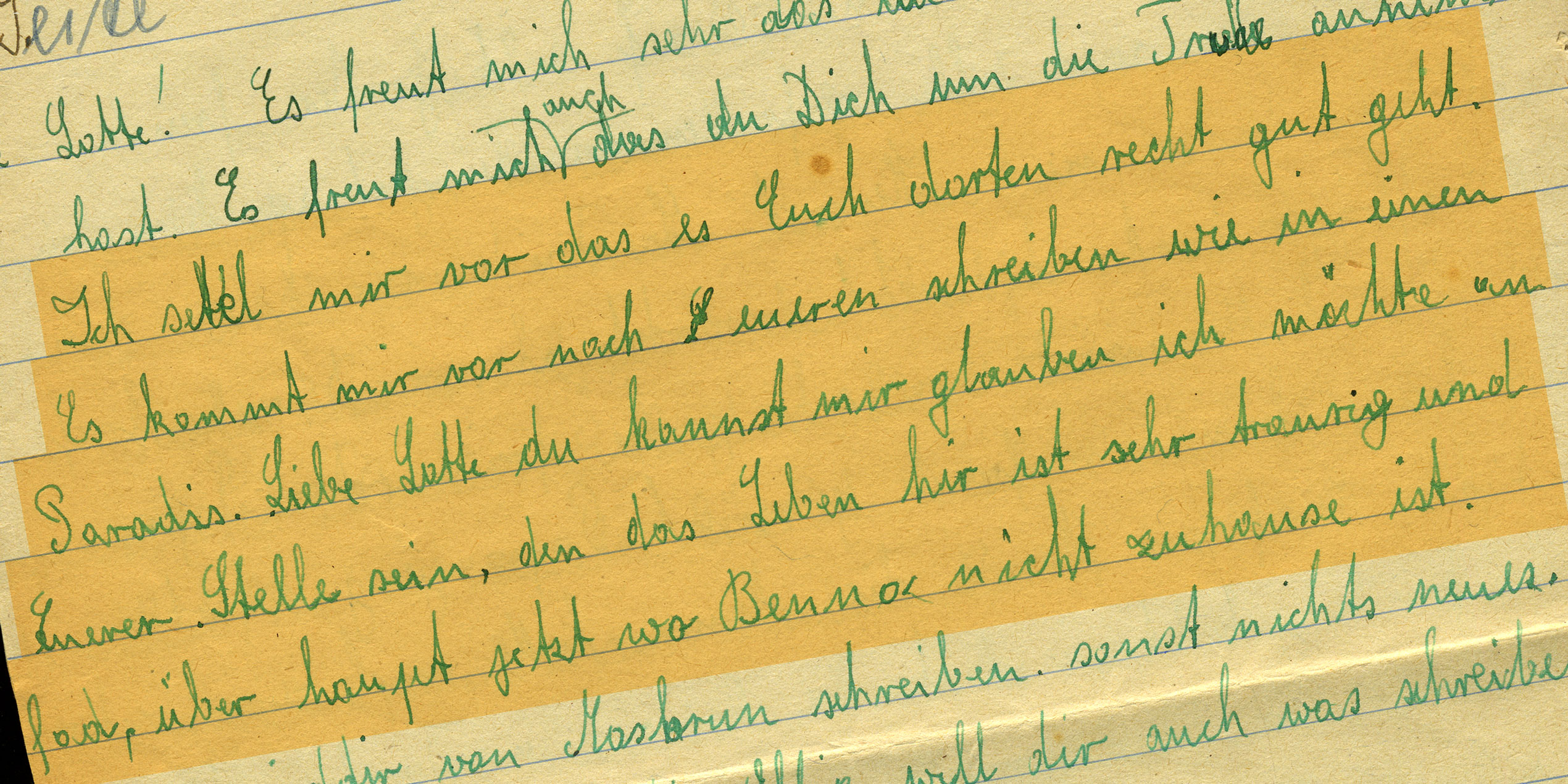

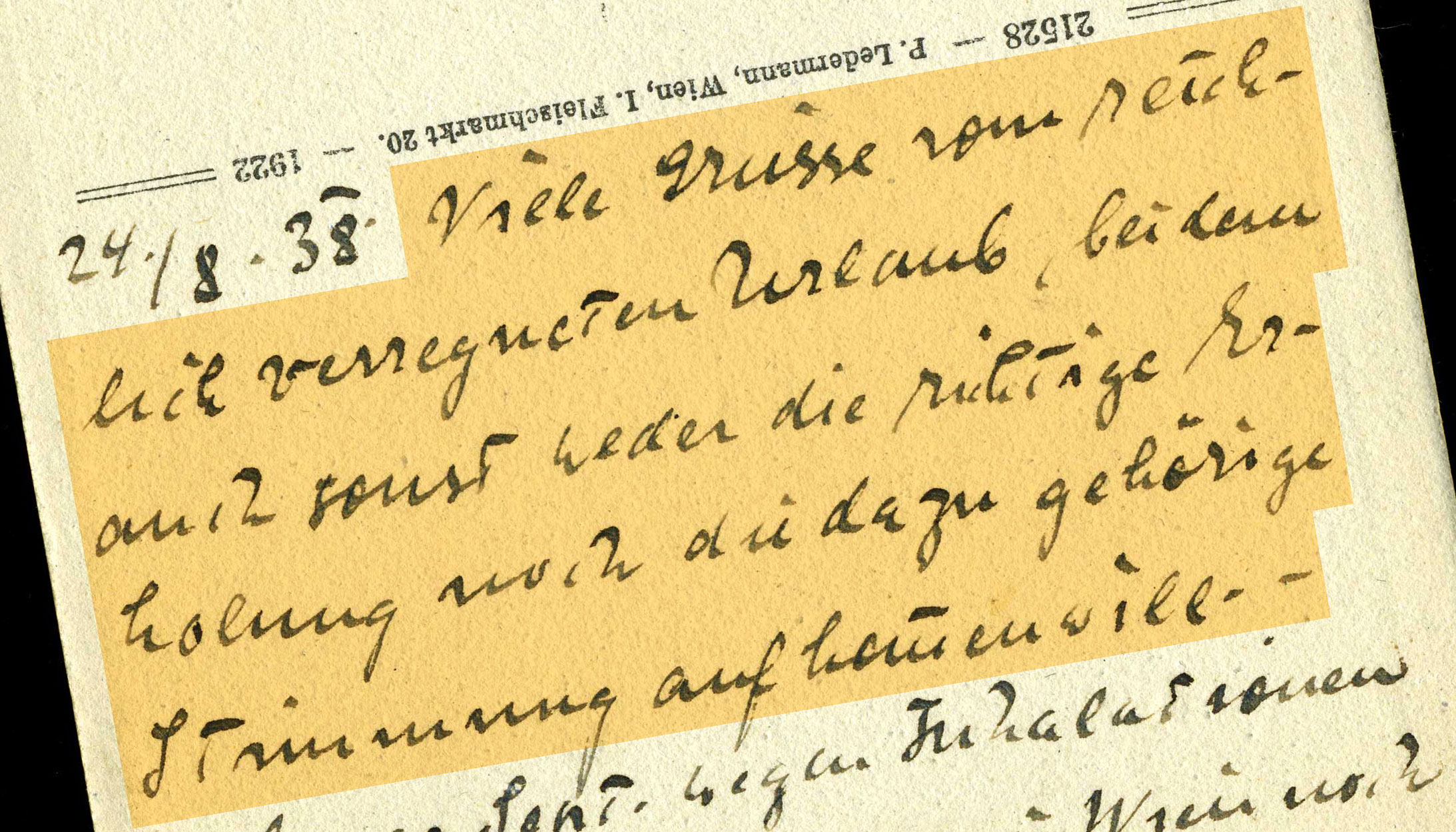

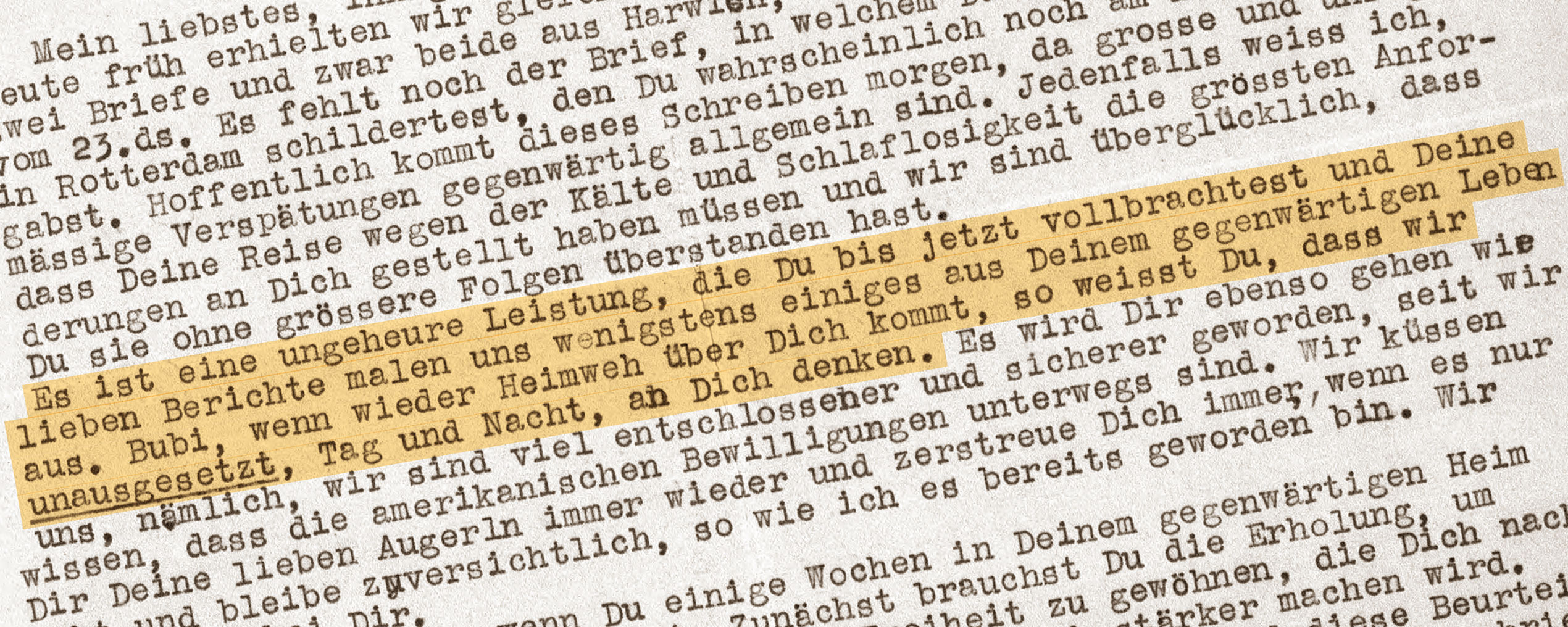

“What you have achieved so far is a tremendous accomplishment, and your lovely reports paint at least part of your present life. Bubi, if you get homesick again, know that we think of you incessantly, day and night.”

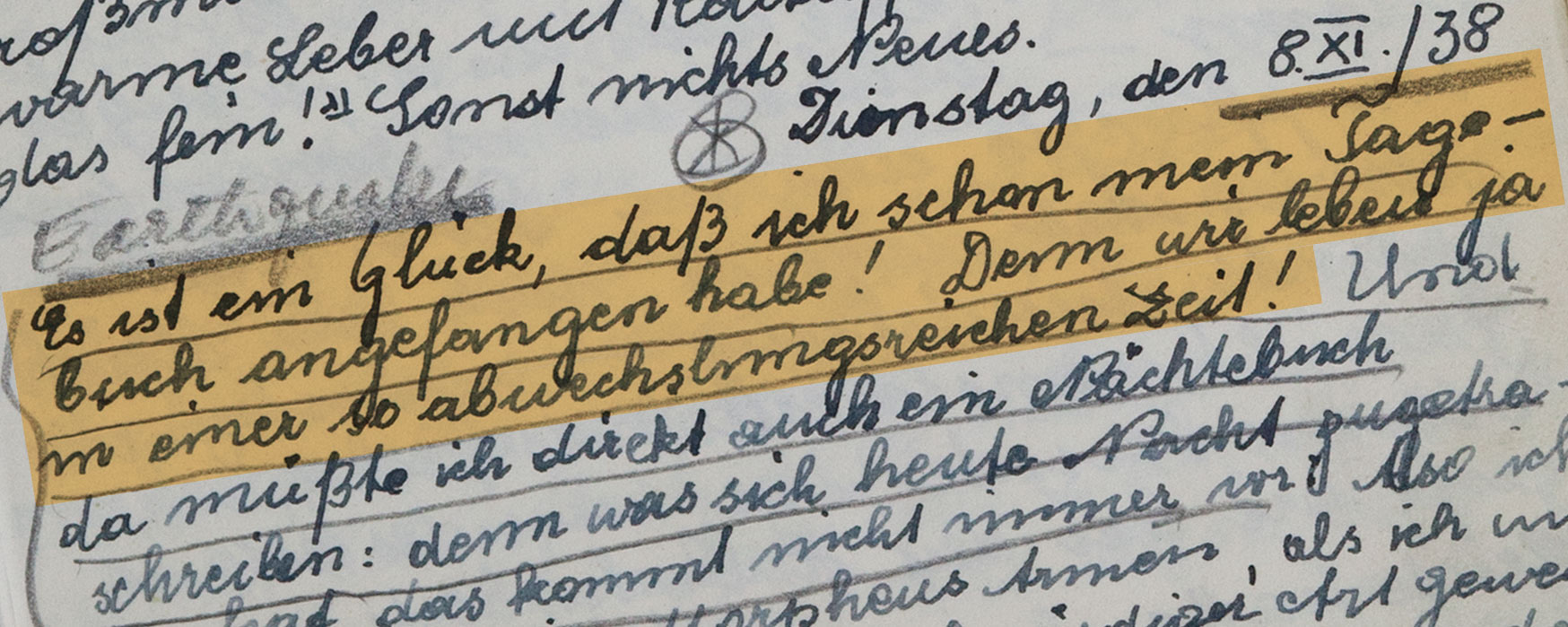

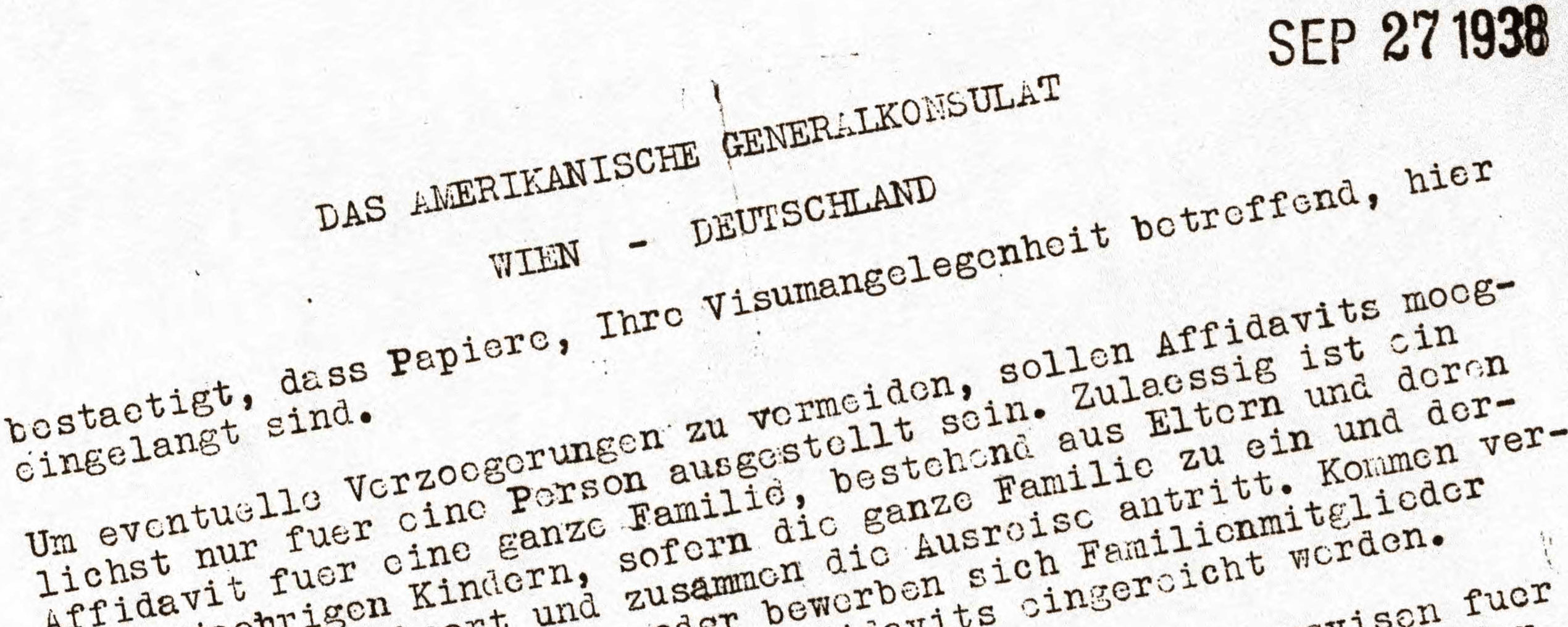

Vienna/Dovercourt, Essex

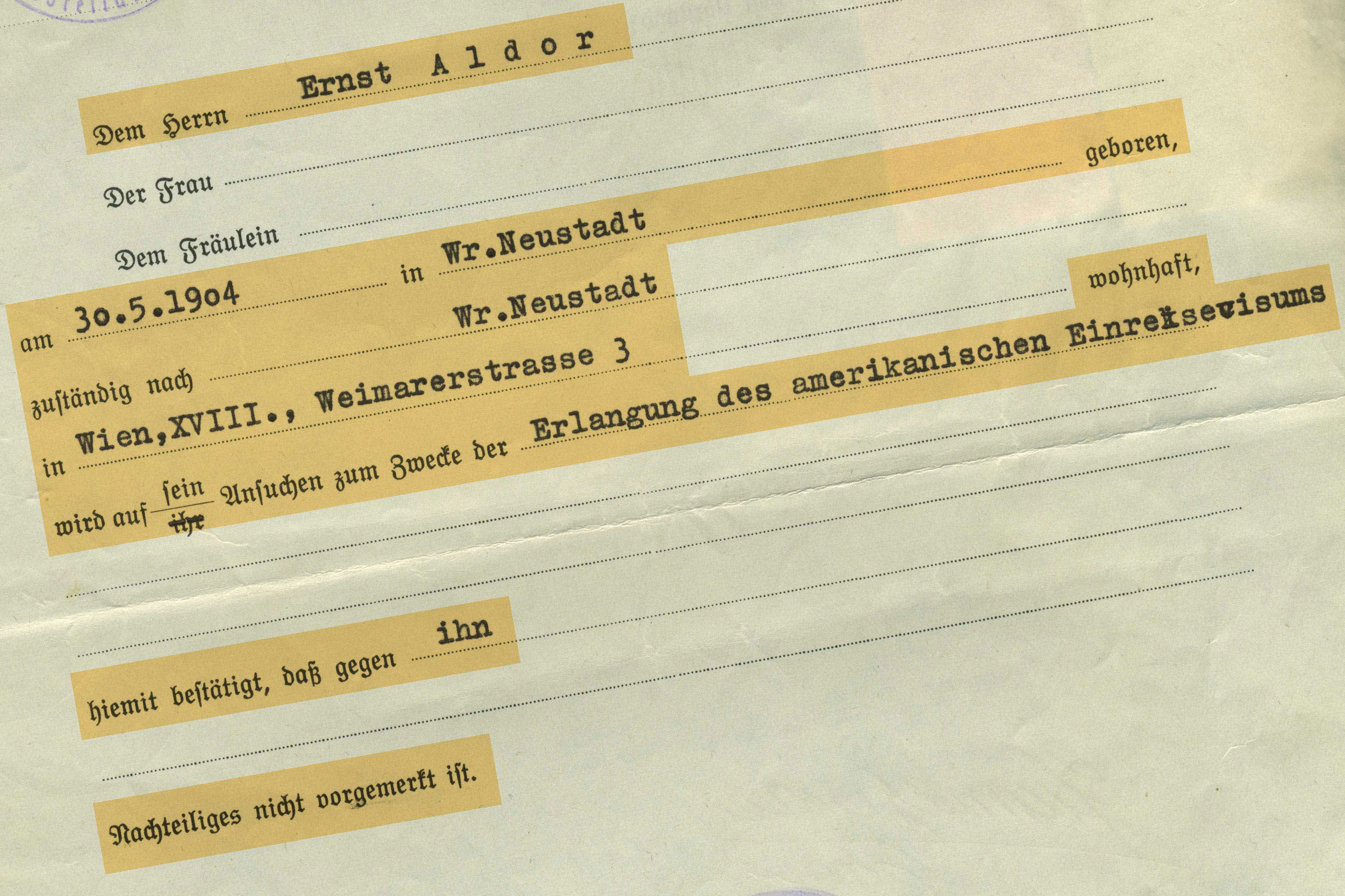

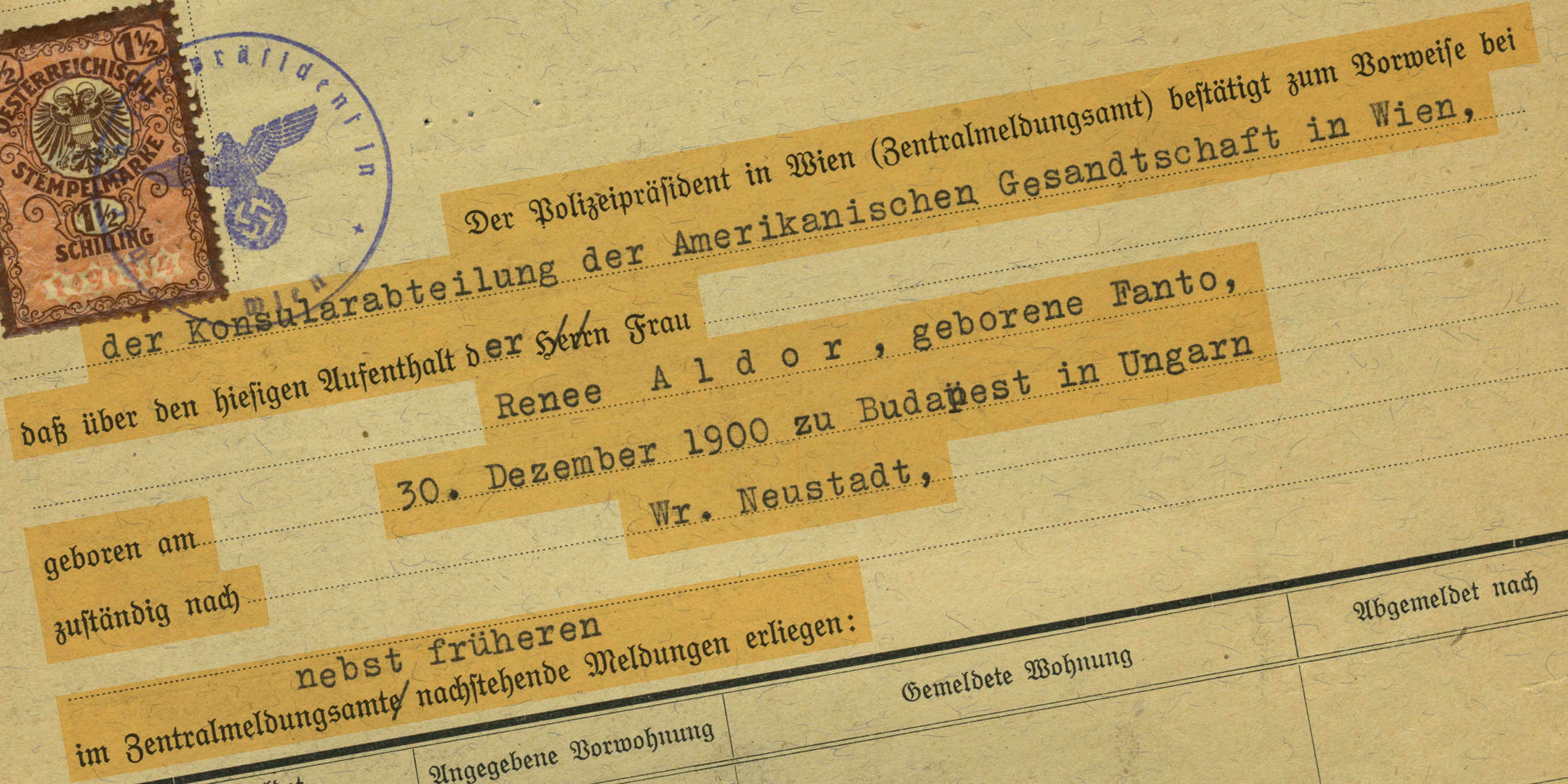

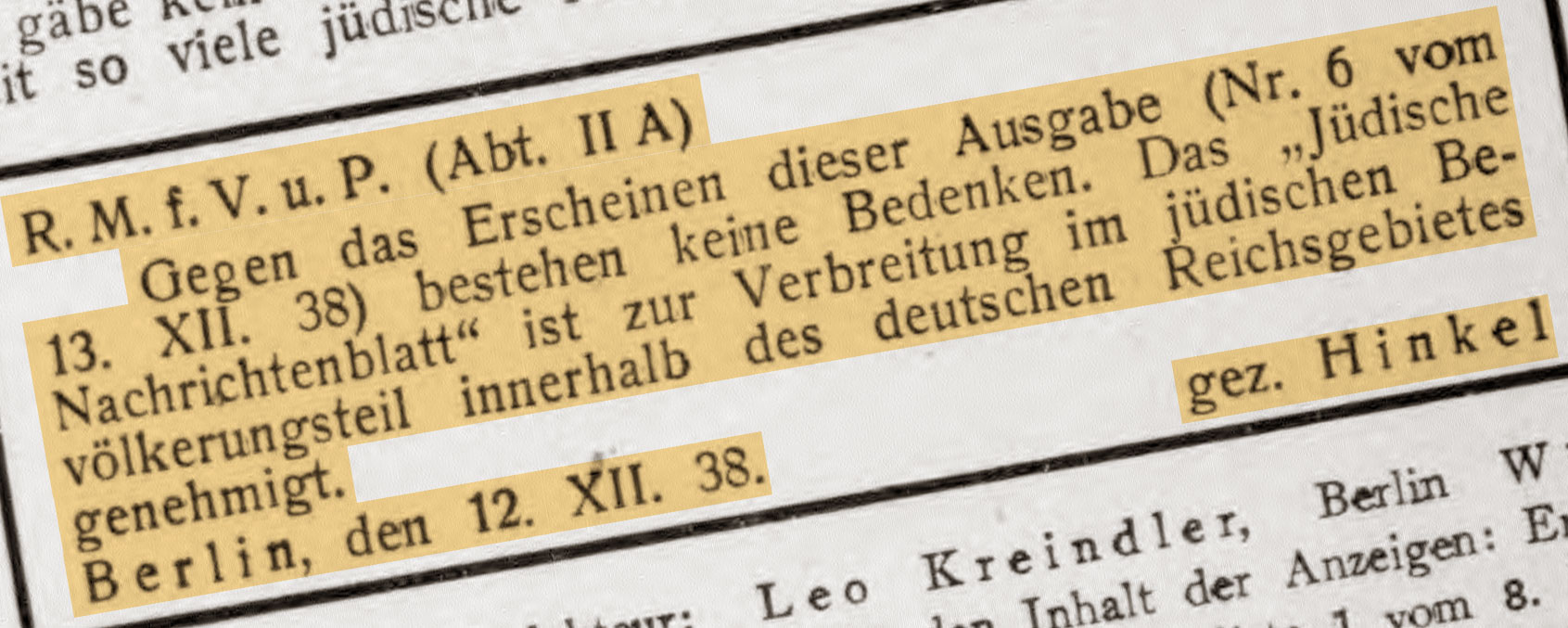

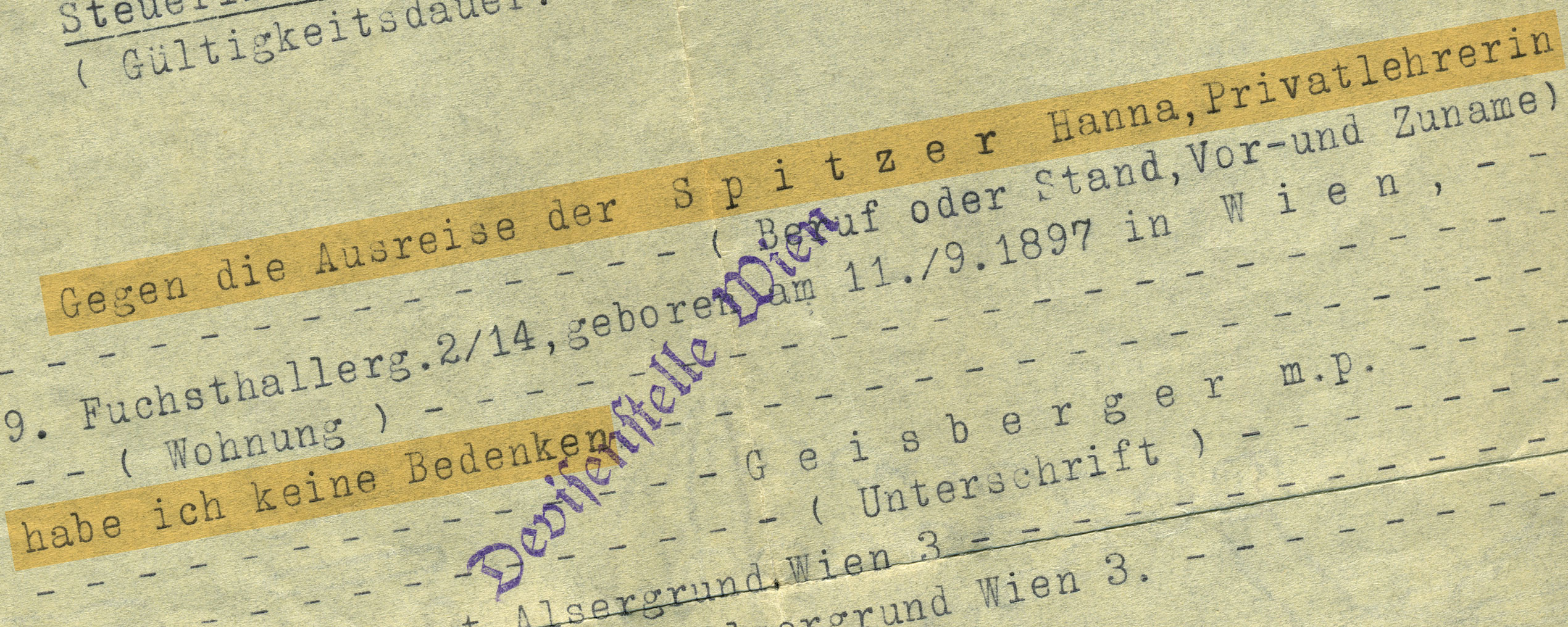

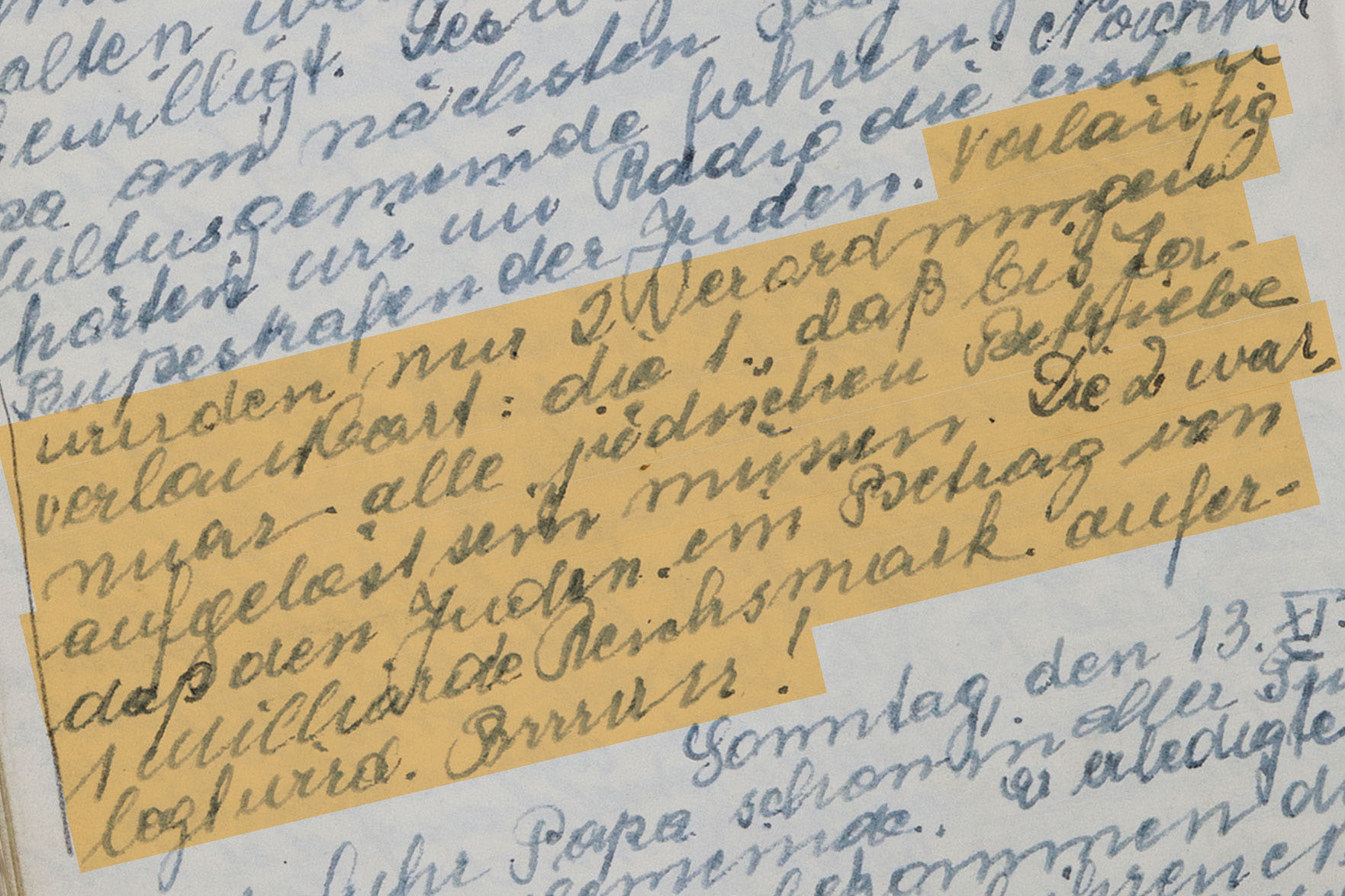

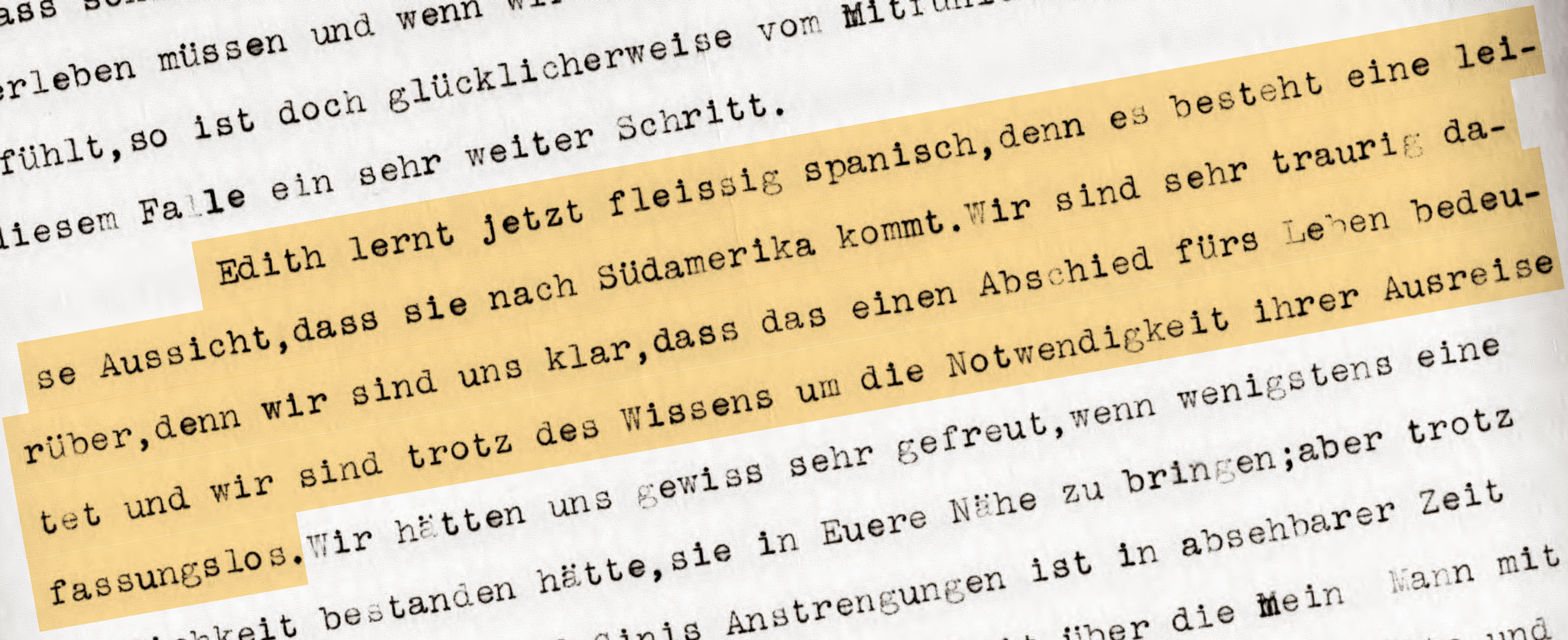

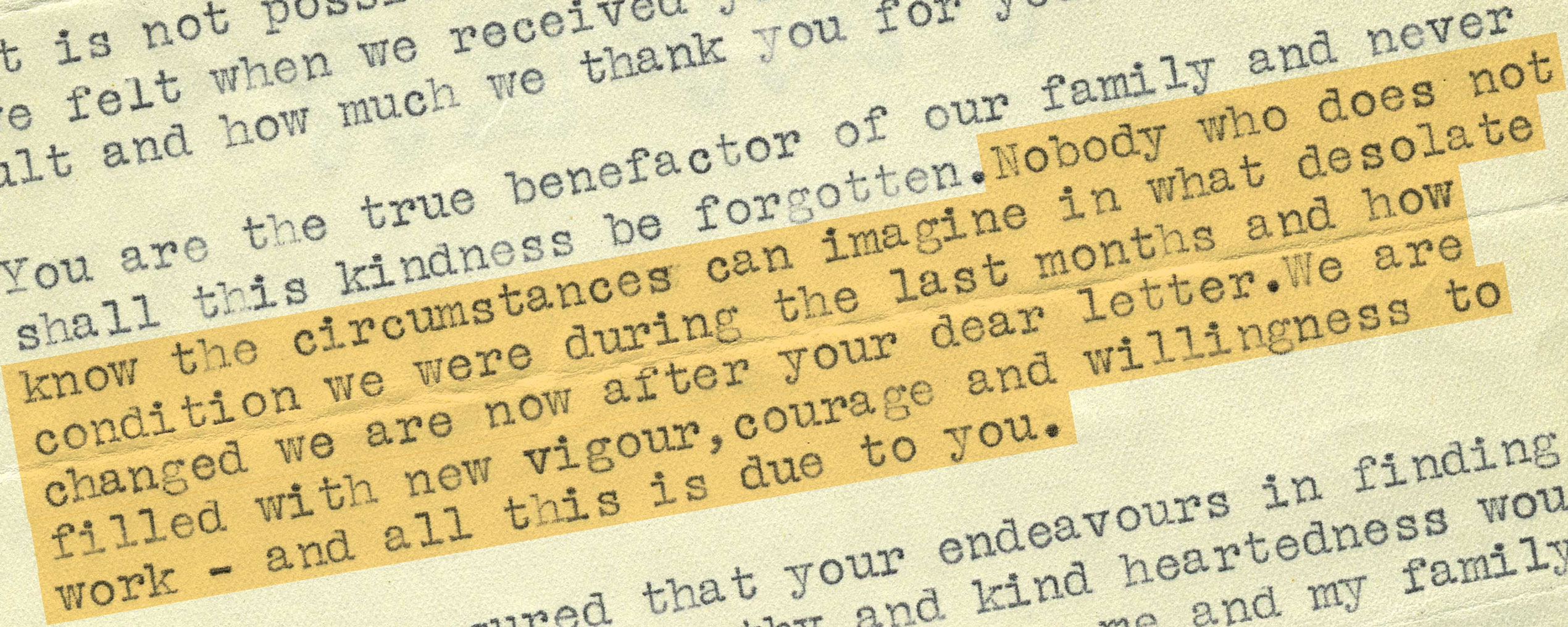

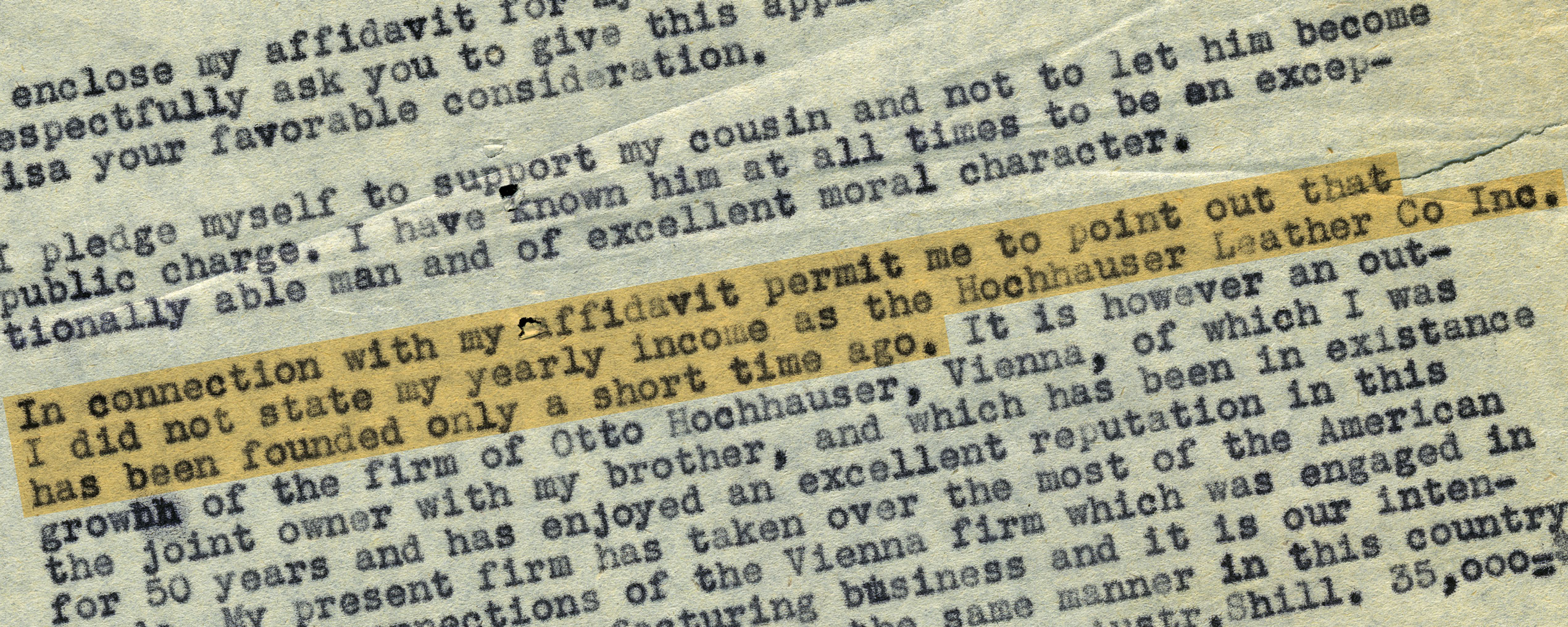

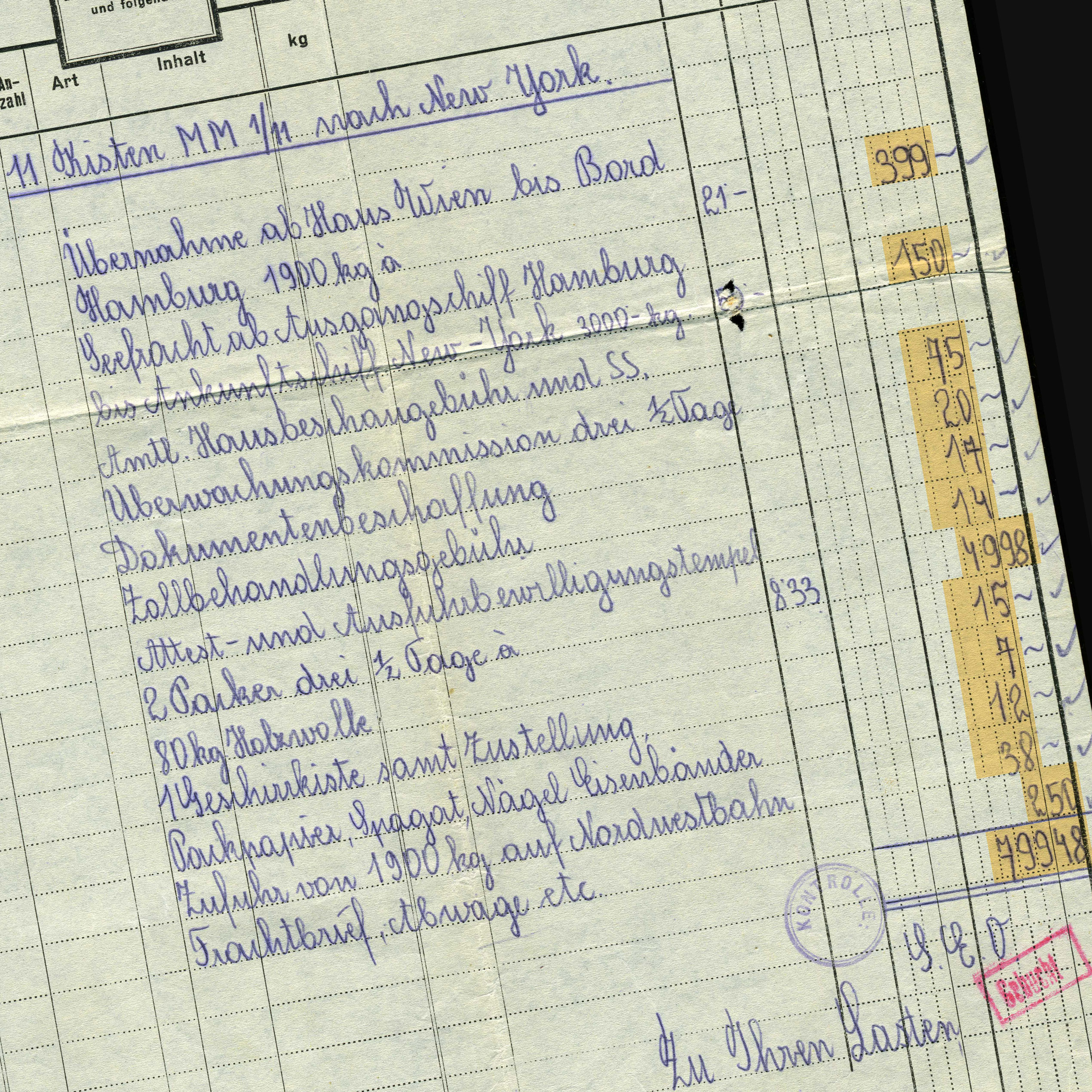

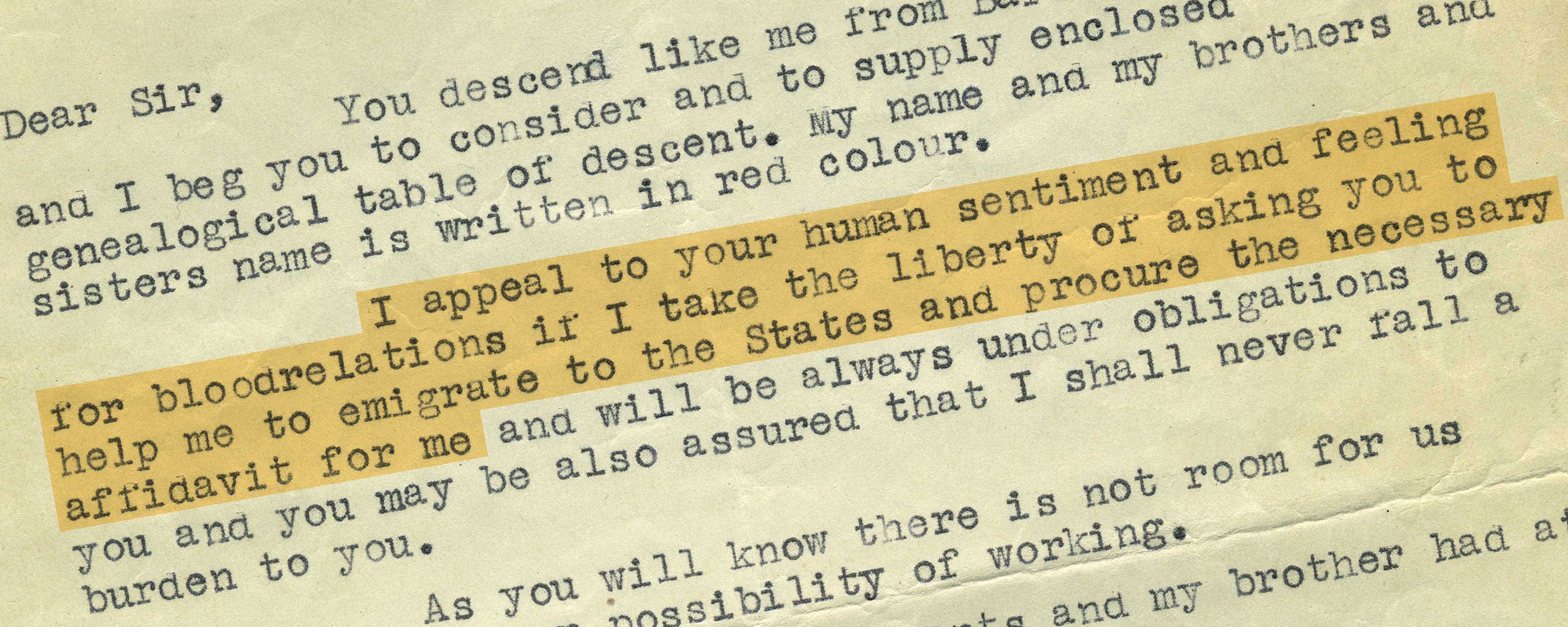

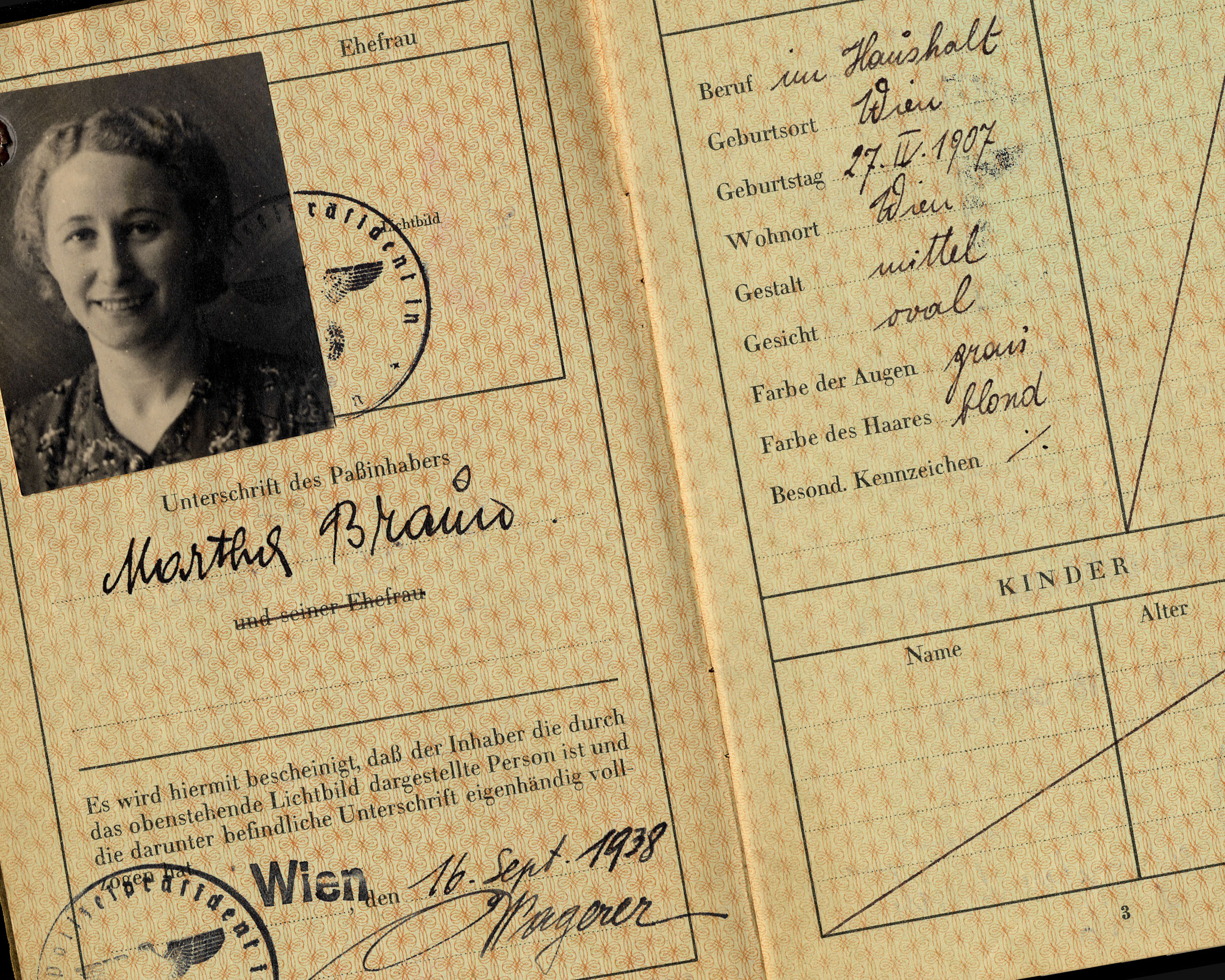

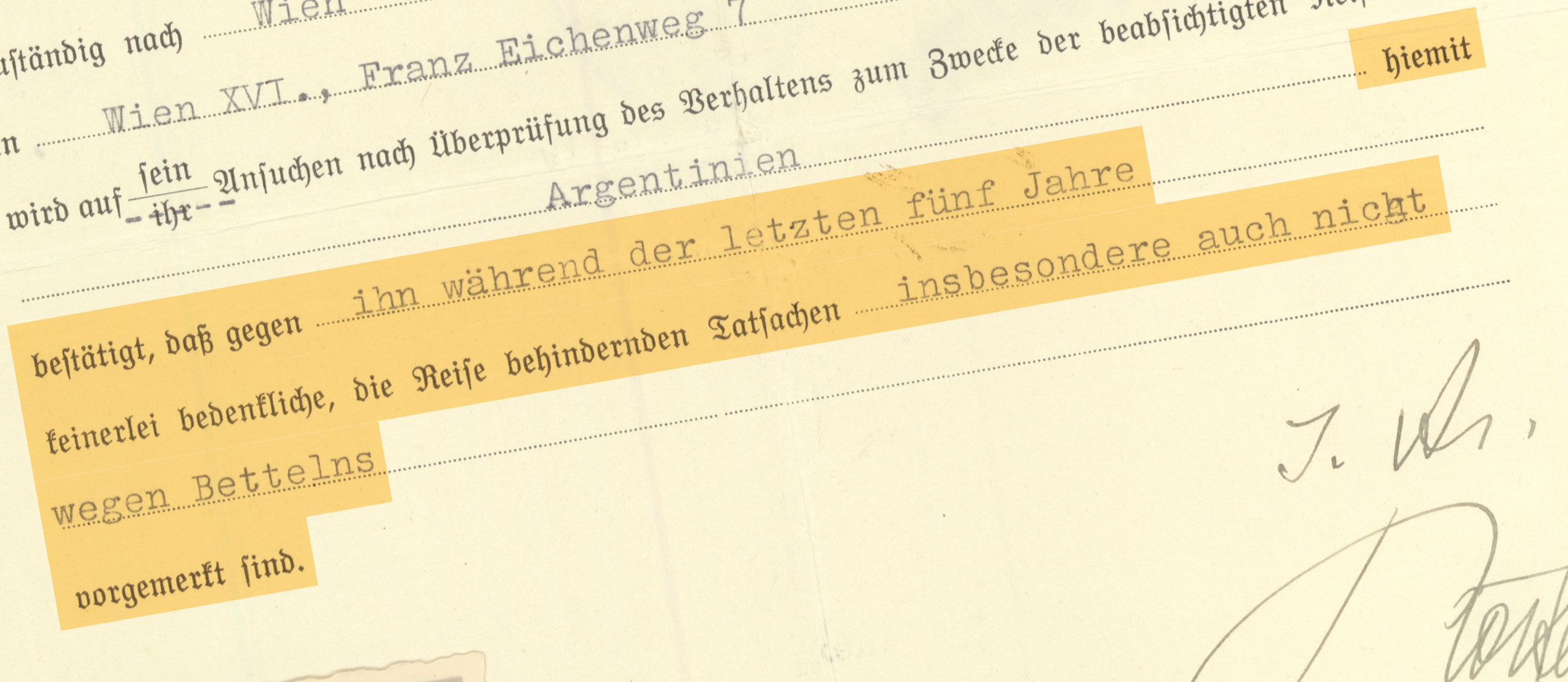

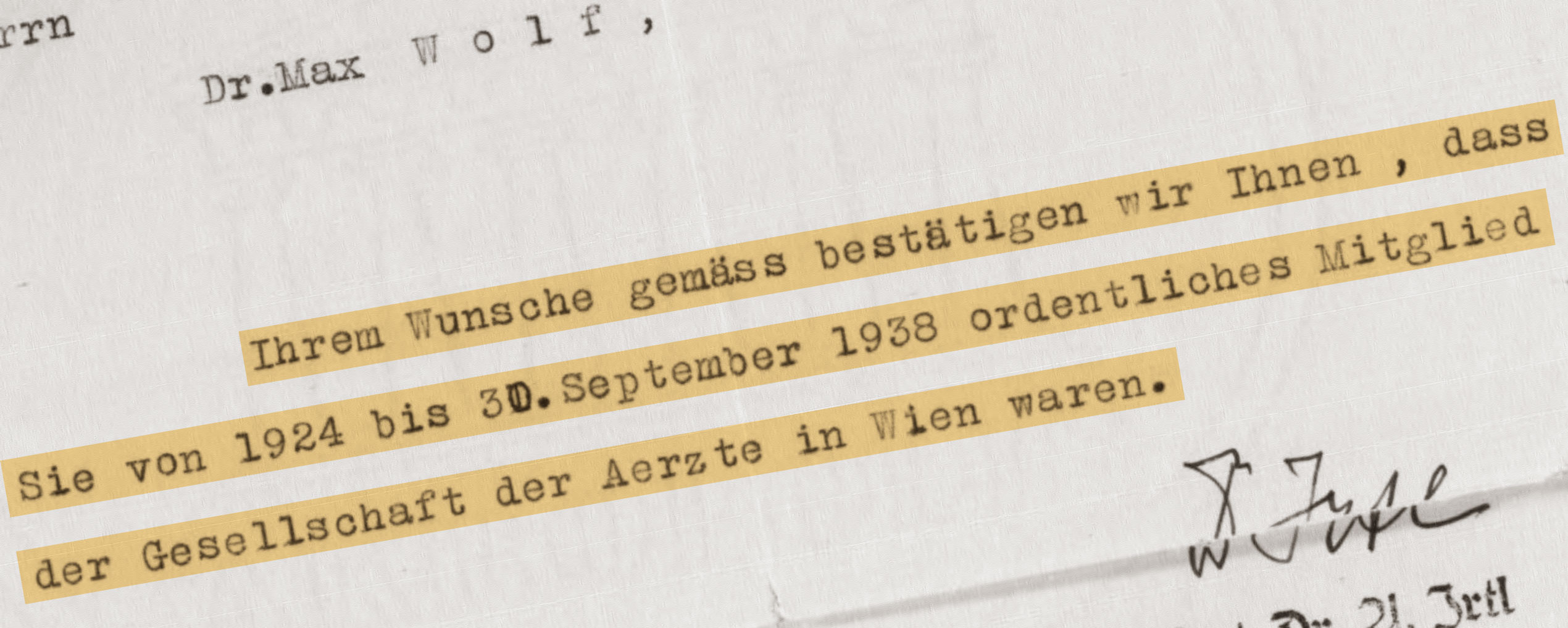

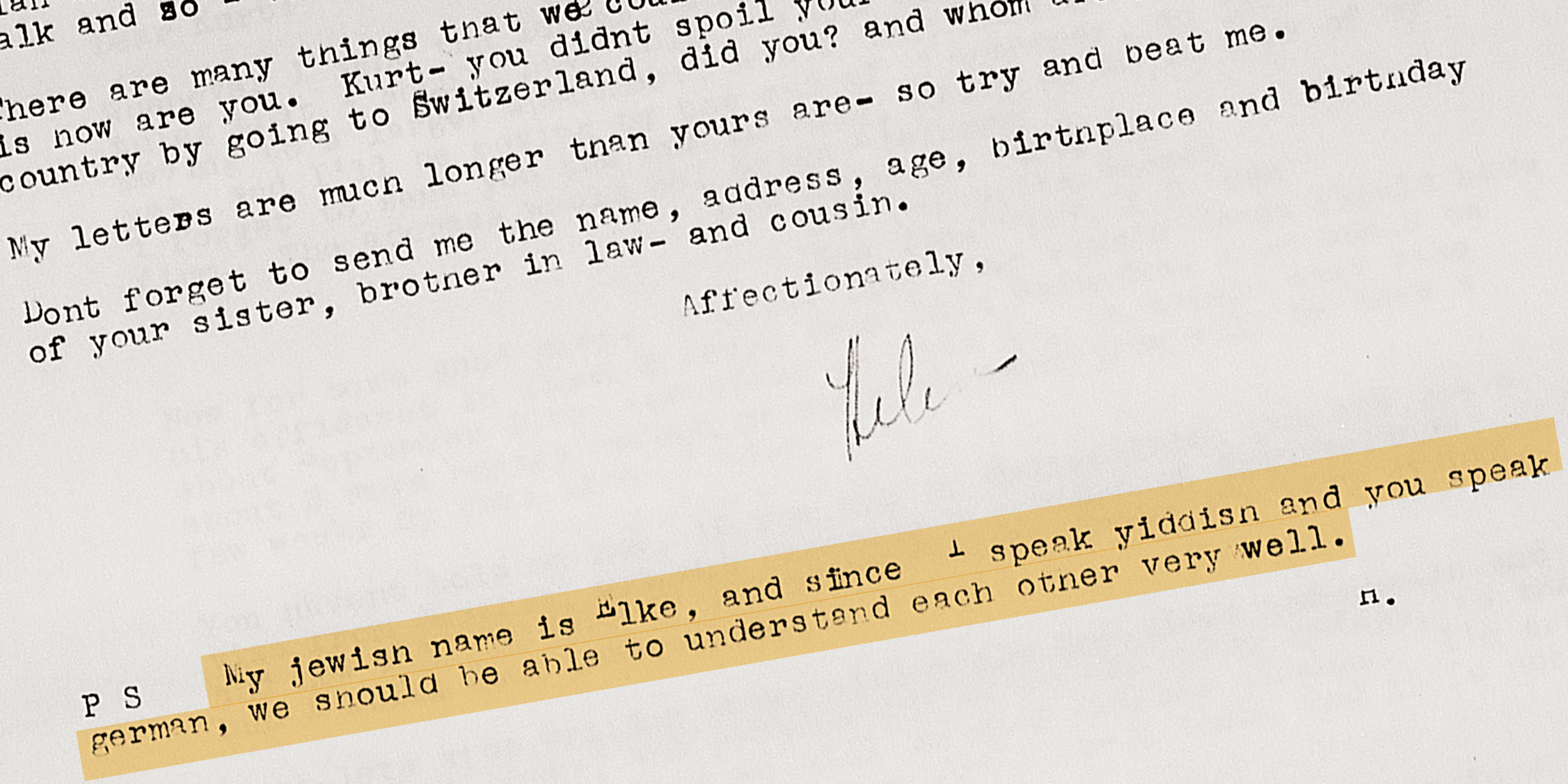

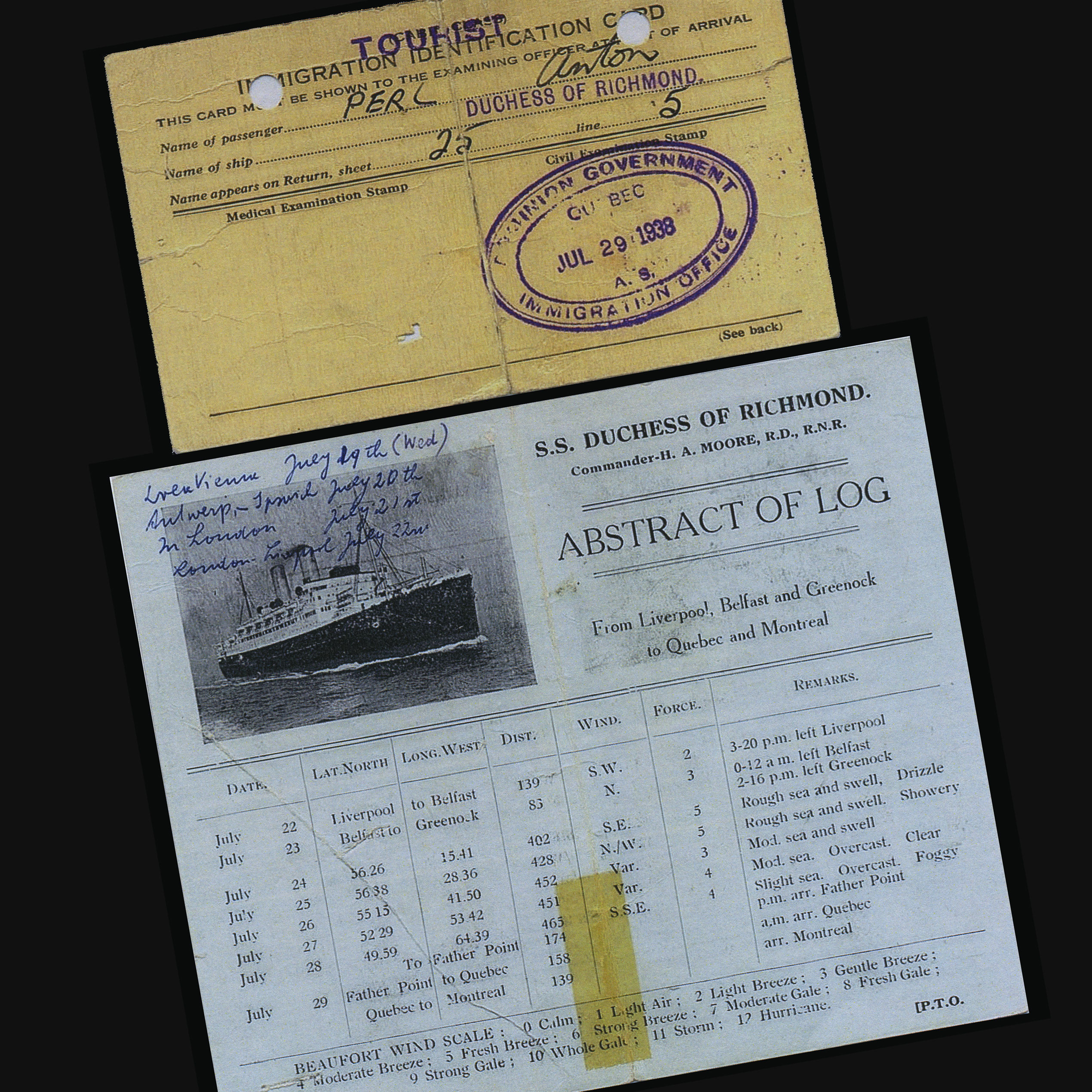

At 16, Heinz Ludwig Katscher was among the older German-Jewish children the British government had agreed to accept as temporary asylees. His parents, the engineer Alfred Katscher and his wife, Leopoldine, as well as his younger sister, Liane, had stayed behind in Vienna. The boy, traveling with a group of youngsters all of whom were too young to go to an unknown place on their own, had clearly expressed feelings of homesickness in his first letters home, since his father refers to the topic lovingly and reassuringly. Even though Mr. Katscher obviously misses his beloved son, he comes across as upbeat: allegedly, the “American permits” are on their way, thanks to which the family is feeling “more determined and secure.” He is exuberant in his praise for his son’s accomplishment in traveling to England without his family and expresses his confidence in the teenager’s ability to make the right decisions regarding his future in England.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Ludwig Katscher Collection, AR 6336

Original:

Box 1, folder A