A History in Imprints

German-Jewish Books as Cultural Artifacts

Rare book collections use descriptive bibliography - detailed documentation of a book’s physical characteristics, such as printing, type, paper, illustrations, collation, paging, and binding - to study books as cultural objects and to trace the history of the people and institutions behind them. This is complemented by traditional enumerative bibliography, which catalogs bibliographic details such as author, title, and publication information.

The first Hebrew books were printed not long after the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, with early centers in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Prague, and Constantinople, and Poland. Beginning in the early 17th century, Amsterdam became a major center for Hebrew book production and trade throughout Europe. Hebrew printing in German lands flourished from the late 17th to the early 18th century, with key centers including Sulzbach, Wilhermsdorf, Fürth, Dyhernfurth, Offenbach, and Berlin. The rise and shifting of Hebrew printing centers reflect, in part, the economic, social, and religious flourishing of the connected Jewish communities.

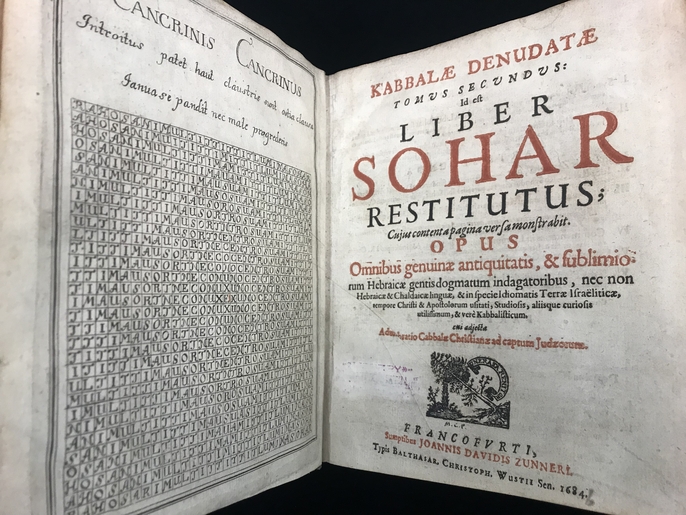

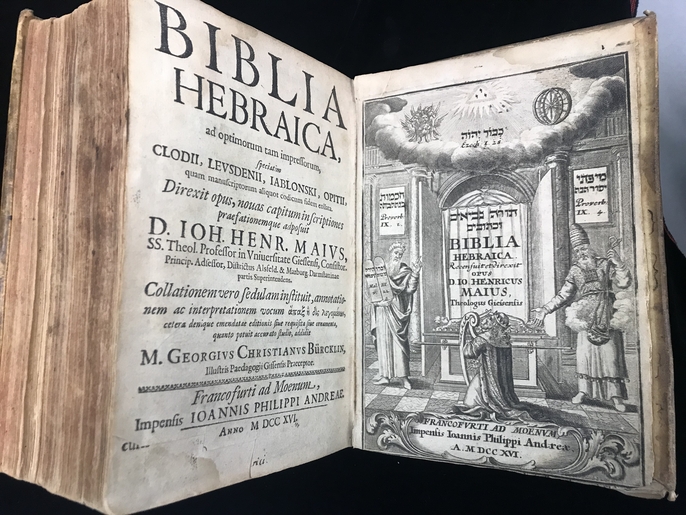

While some Hebrew presses were owned by Christians and catered to the scholars of Jewish texts known as "Christian Hebraists," this article examines books printed by and for Jews. Looking at German-Jewish history through the lens of book printing for the Jewish community highlights the survival of Jewish books despite censorship and persecution. Here are three examples that show how focusing on a book's imprint through descriptive bibliography documents the interconnection between Hebrew book printing and German-Jewish history.

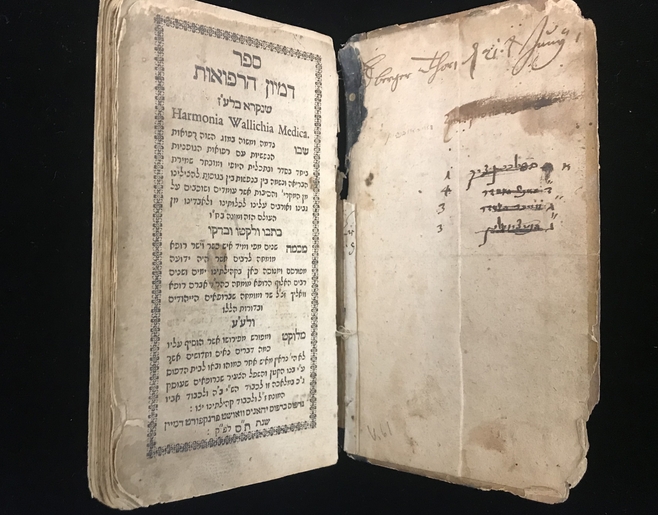

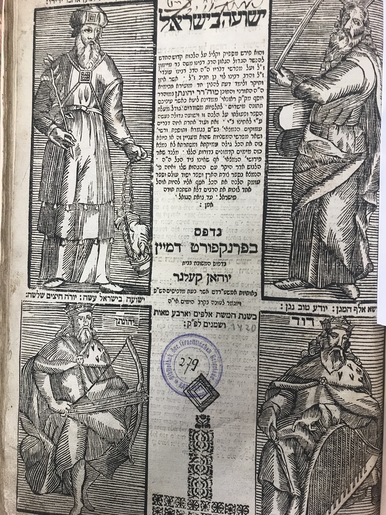

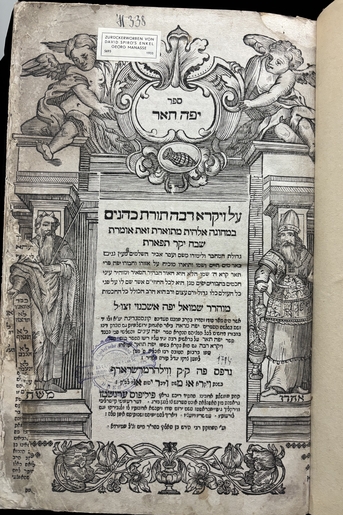

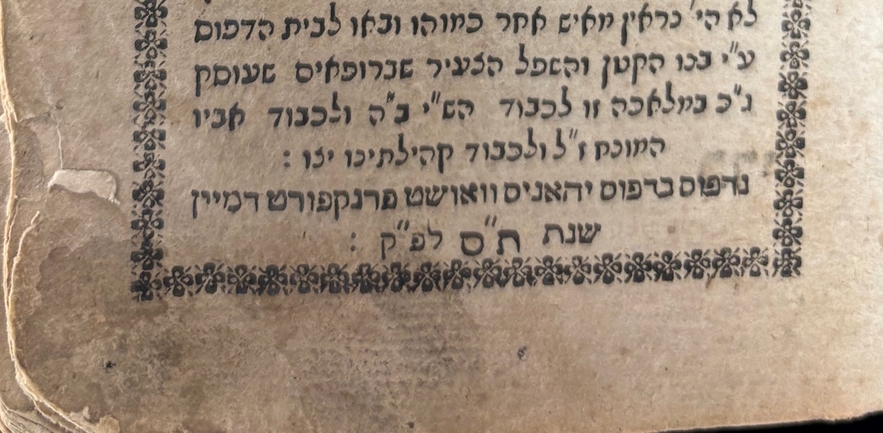

Recording the imprint through descriptive bibliography helps identify the different roles in the production of a book. These roles could include the printer, who was responsible for deciding the the size of the pages and how they are put together; the "entrepreneur," who provided the money to have the book printed; as well as the typesetter putting the type together on a page. This copy of Abraham Wallich's treatise of popular medicine, Sefer Refu'ot (or Harmonia Wallichis Medica in Latin) (LBI Library, r R 133 W2 1700) exemplifies the unique history of Hebrew printing in Frankfurt am Main.

Jews were forbidden from setting up their own print shops in the 17th and most of the 18th centuries. Thus the Jewish community would often fund the printing of their texts through a Christian printer. Wallich's book was " [...] mi-pi umi-yad ... Avram Rofe Ṿolikh ... u-vaʼu le-vet ha-defus ʿa.y. beno ha-ḳaṭan [...]" ("from the mouth of Abraham Wallich and brought to the printing house by his son"), indicating his son's financial support of the publication. Wallich's treastise was "Nidpas bi-defus Yohanes Ṿuśṭ Franḳfurṭ de-Mayn" ("printed by Johannes Wust Frankfurt am Main") in 1700.

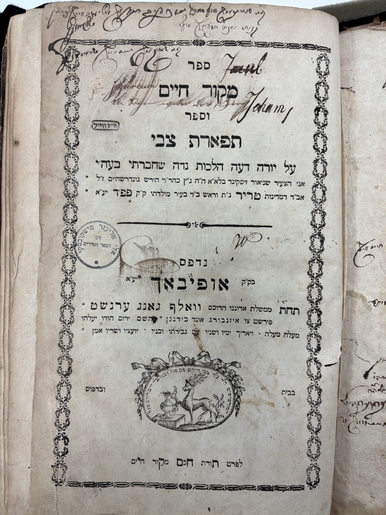

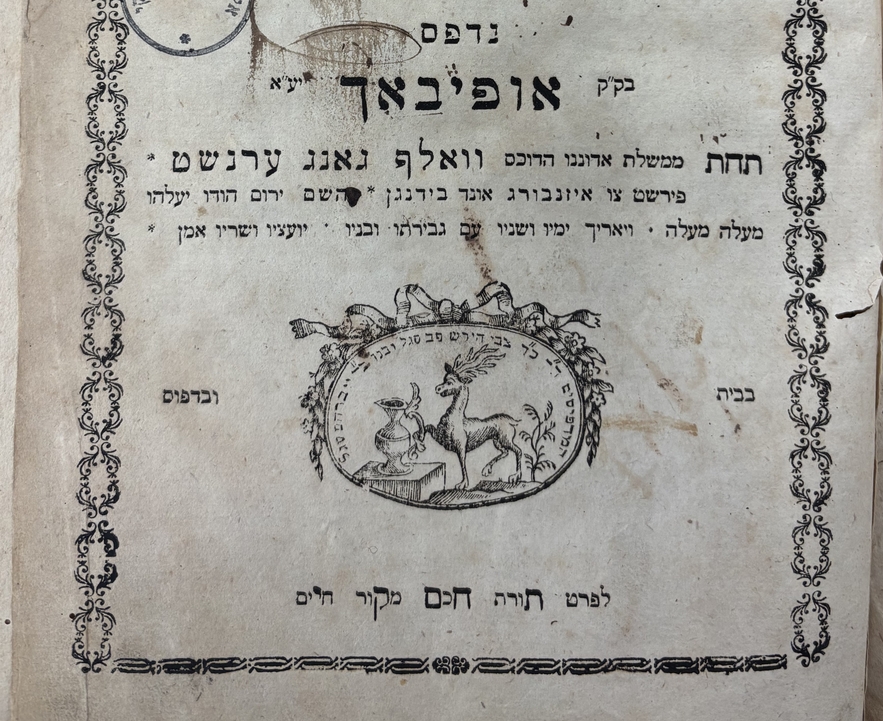

In the 18th century, more Jewish printers were able to set up their own print workshops in Germany, in some cases with economic gains for the local community. In Offenbach in 1763, the "Schutzjude" ("protected Jew") Hirschel Isaac from Pressburg (Bratislava) was granted the privilege to set up a Hebrew print shop by Duke Wolfgang Ernst II of Isenberg and Büdingen, who was known for his liberal economic developments that included showing a greater openness toward Jewish businesses. Hirschel Isaac paid 20 Gulden annually for the privilege of printing in Offenbach and was eventually joined by his son.

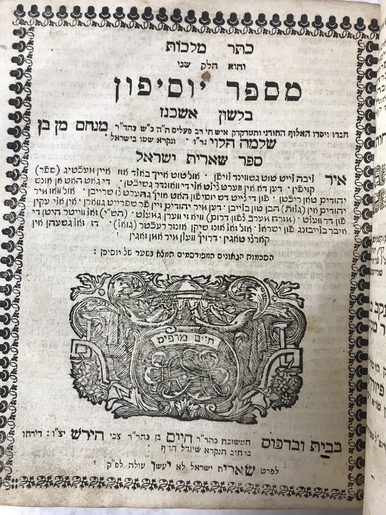

On the title page of Sefer Mekor Hayim (LBI Library, r (f) 215), Hirschel Isaac very prominently praises the man who granted him the privilege, printing his name in bold letters. "Nidpas be k.k. Offenbach [...] tachat mimshlat adonenu hadukas Wolf Gang Ernsht [...]." On the title page, the printer's name appears inside the printer's mark: "ha-Madpisim ... Zvi Hirsch P.B. [Pressburg] Segal ve-benach ... Abraham Segal" ("By the printers Zvi Hirsch Segal of Pressburg and his son Abraham Segal"). The printer's mark shows a deer (probably for the names "Zvi" and "Hirsch," the words for "deer" in Hebrew and German, respectively) and a pitcher, representing the flow of knowledge from the father to the son, surrounded by a wreath.

German-Jewish print workshops were often founded by a printer who learned his trade somewhere else – often in printing centers such as Prague and Amsterdam – and set up in Germany, where he handed down his knowledge to others in his family. Printers traveled to where there was a need. For example, Isaac Cohen Jüdels came from the well-known family of Prague printers, the Gersonides, and established print shops in both Wilhermsdorf and Sulzbach. Some printers were forced to migrate as a result of persecution, such as the printers in Vienna, who were expelled in 1670. One such printer was Aaron Frankel, the son of Viennese exiles, who began his own workshop in Sulzbach in 1699 after working under Isaac Cohen Jüdels's successor, Moses Bloch. The Frankel family continued printing in Sulzbach for decades after Aaron Frankel's death.

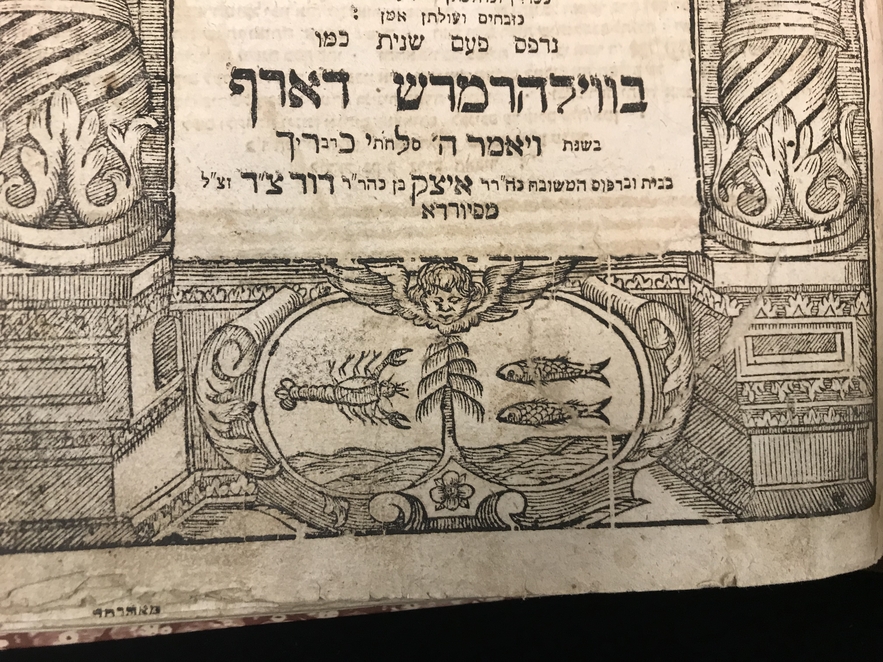

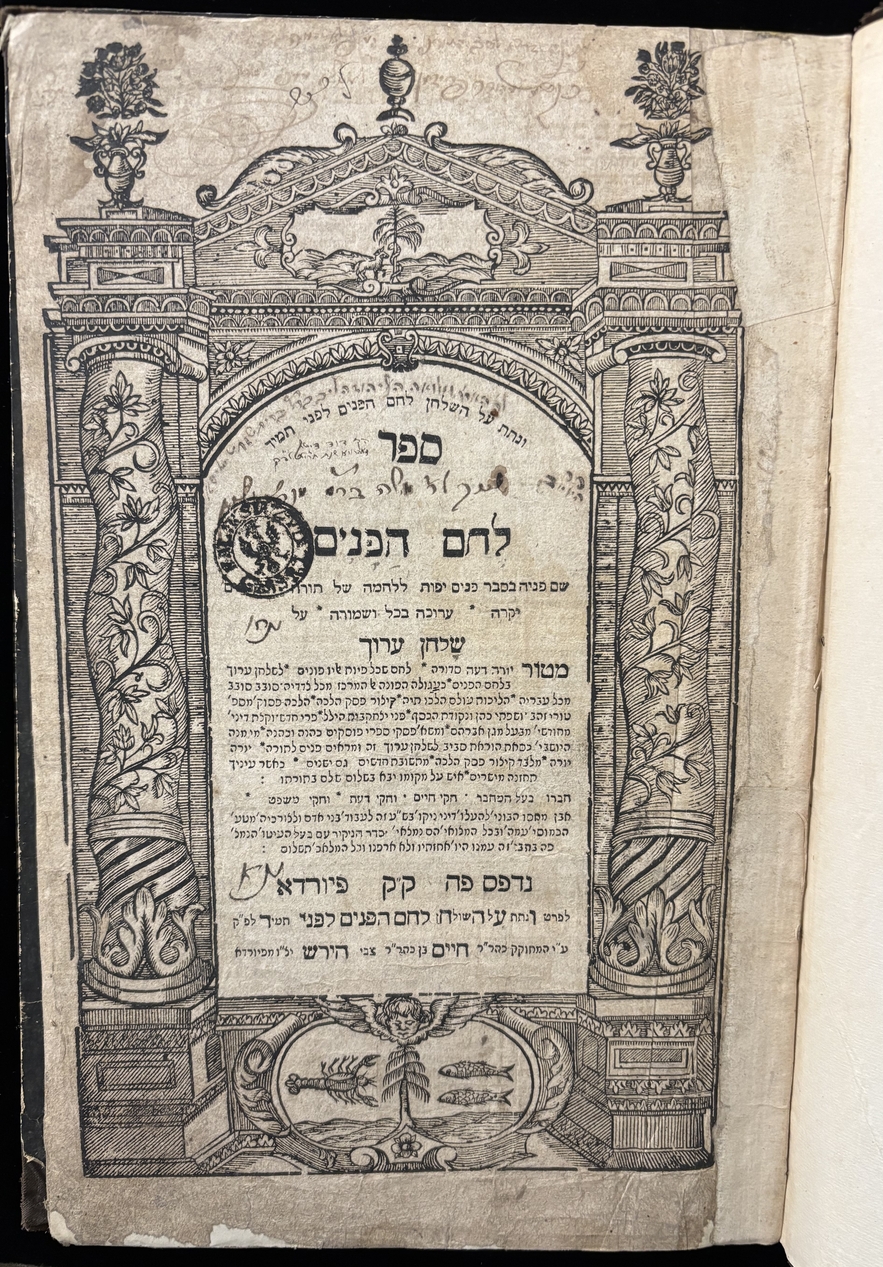

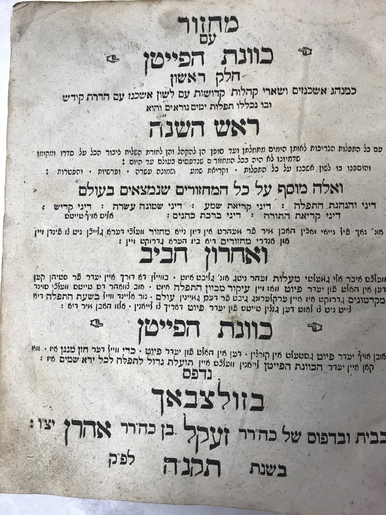

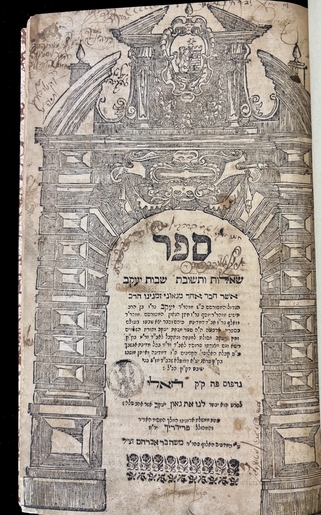

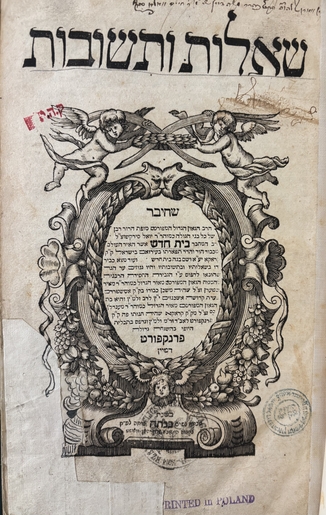

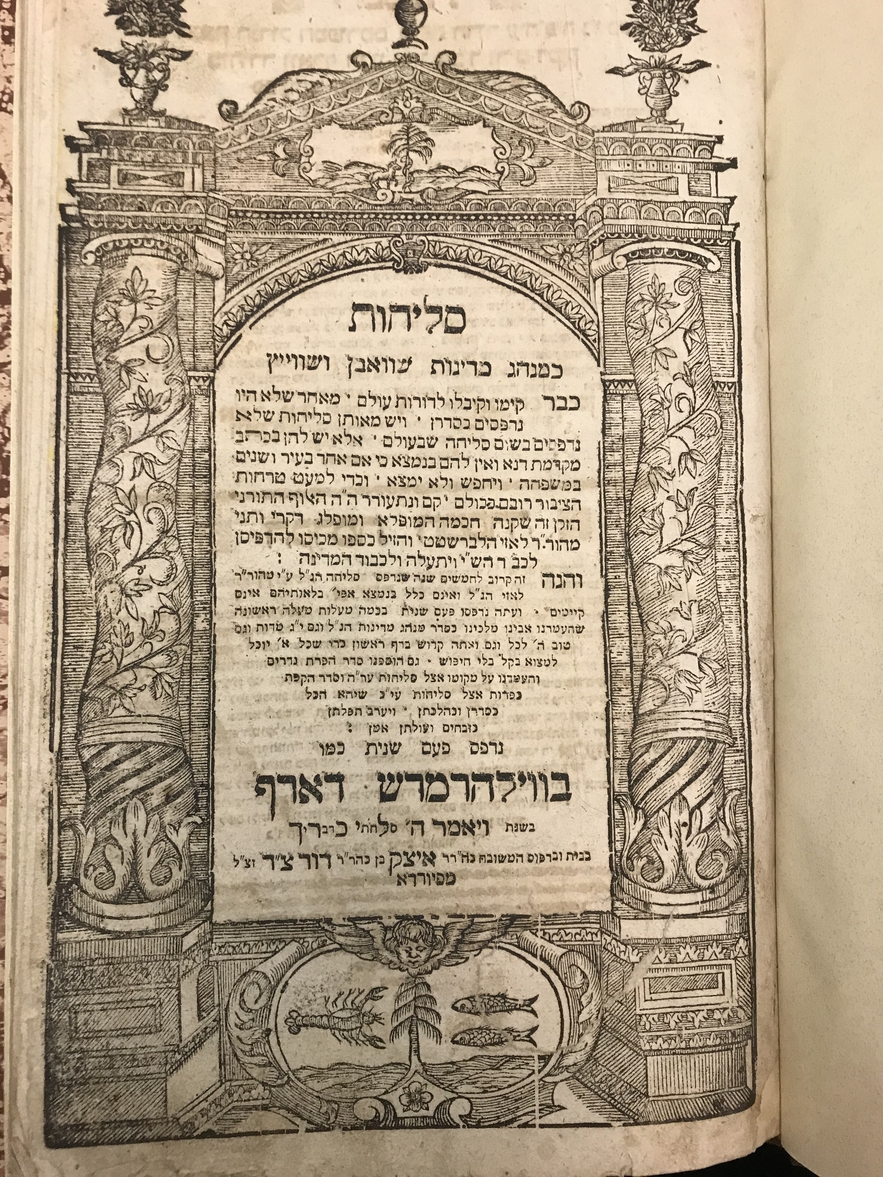

This copy of Selihot ke-minhag medinot Svaben uve Sveis ("Prayers according to Swabia and Switzerland") provides an example of how printing workshops were handed down in families. On first glance, this copy of prayers prominently states that it was printed in Wilhermsdorf. However, a closer reading shows that this printing statement reads "nidpas paʿam shenat kemo be-Wilhermsdorf" ("reprinted once again as in Wilhermsdorf")

The prominence of Wilhermsdorf is deceptive, because the place of publication is hidden in the printing statement, which reads: be-vet u-ve-defus ... Itsaḳ ben ... Daṿid Z.D. mi-Fiyorda ("held and printed by Itsak ben David Zirndorfer of Fürth"), meaning the book is the second edition of the copy first published in Wilhermsdorf, but now published in Fürth. For comparison, the imprint of first edition, published in 1737, reads "Nidpas Be-Wilhermsh Dorf" ("printed in Wilhermsdorf") by Hirsh ben Hayim. The similarities between these two title pages shows how printing presses were handed down. Hirsh ben Hayim was active in Fürth and Wilhermsdorf from 1683 to 1767.

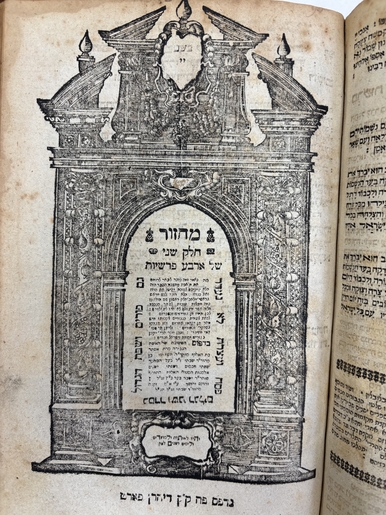

Both books have identical printer's marks showing an angel over a tree of life. On one side is a crab, the zodiac symbol of Capricorn (representing the month of Tammuz). The other shows two fishes, the zodiac symbol for Pisces (representing the month of Adar). The architectural border surrounding the title is designed to look like a portal. Zirndorfer most likely imitated his predecessors, using their printer's marks and title page engravings. The use of this identical printer's marks and architectural border shows the interconnection of the Hebrew printers.

Hirsh ben Hayim handed his workshop down to his son, who was active in Wilhermsdorf and Fürth until 1774. His widow transferred his press to Isaac Zirndorfer after they married in 1775. The title pages of both editions – the first edition by Hirsh ben Hayim and the second by Zirndorfer – are very similar. A title page by Hirsh ben Hayim's son, Hayim Zvi Hirsh, is nearly identical to the prayer book printed by David Zirndorfer.

Through these examples, we can trace the development of Hebrew printing for Jewish communities in Germany from its origins in Christian-owned presses, to workshops set up by Jewish printers who migrated from other printing centers, to an intergenerational tradition of local printing.

Bibliography:

Belanger, Terry. "Descriptive bibliography." Book collecting : a modern guide. New York: Bowker, 1977. Pages 97-115.

Breger, Jennifer. "Printing, Hebrew." Encyclopaedia Judaica. Second edition. pages 529-540.

CERL Thesaurus. Consortium of European Research Libraries. Viewed online September 5, 2025.

The Hebrew Book : an historical survey. Edited by Raphael Posner and Israel Tashema. New York: Leon Amiel ; Jerusalem : Keter, 1975.

Schmelzer, Menahem. "Hebrew printing and publishing in German, 1650-1750 : on Jewish book culture and the emergence of modern Jewry." Leo Baeck Institute Year Book. Vol. 33 (1988) 369-383 pages.

"Typography" Jewish encyclopedia. New York and London : Funk and Wagnalls Company, 1907.

Yaari, Abraham. Hebrew printers' marks from the beginning of Hebrew printing to the end of the 19th century. Jerusalem : The Hebrew University Press Association, 1943. (Hebrew pages translated with Google translate).

Zur Geschichte der Juden in Offenbach am Main. Band 2. Von den Anfaengen bis zum Ende der Weimarer Republik. Offenbach am Main: Magistrat der Stadt, 1990. pages 70-71.