Contradictory messages

The Nazi press agency spreads misinformation

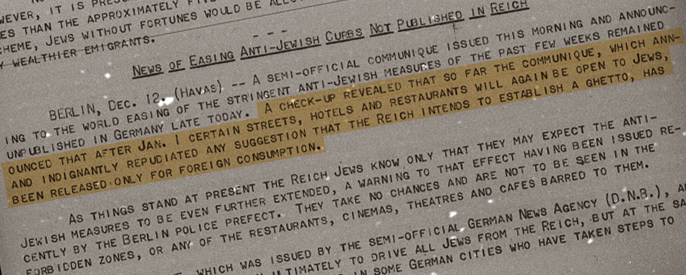

[original] “A check-up revealed that so far the communique, which announced that after Jan. 1 certain streets, hotels and restaurants will again be open to Jews, and indignantly repudiated any suggestion that the Reich intends to establish a ghetto, has been released only for foreign consumption.”

Berlin

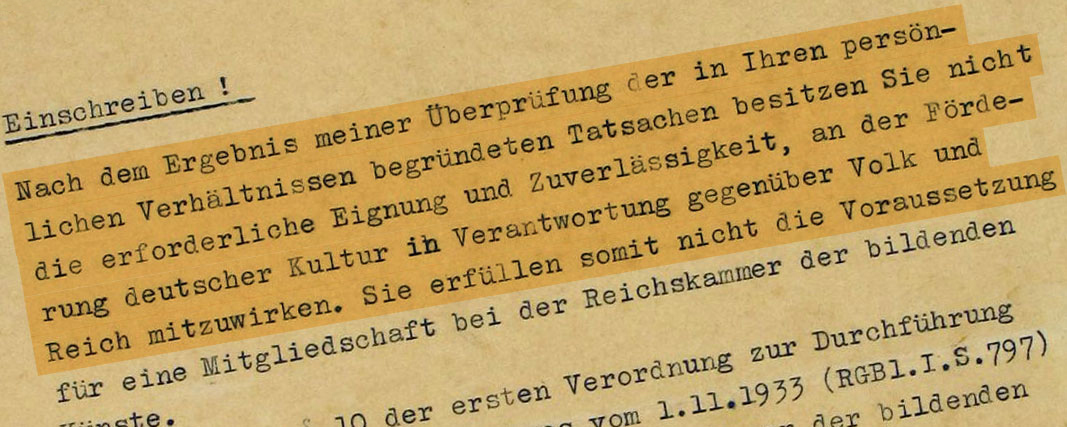

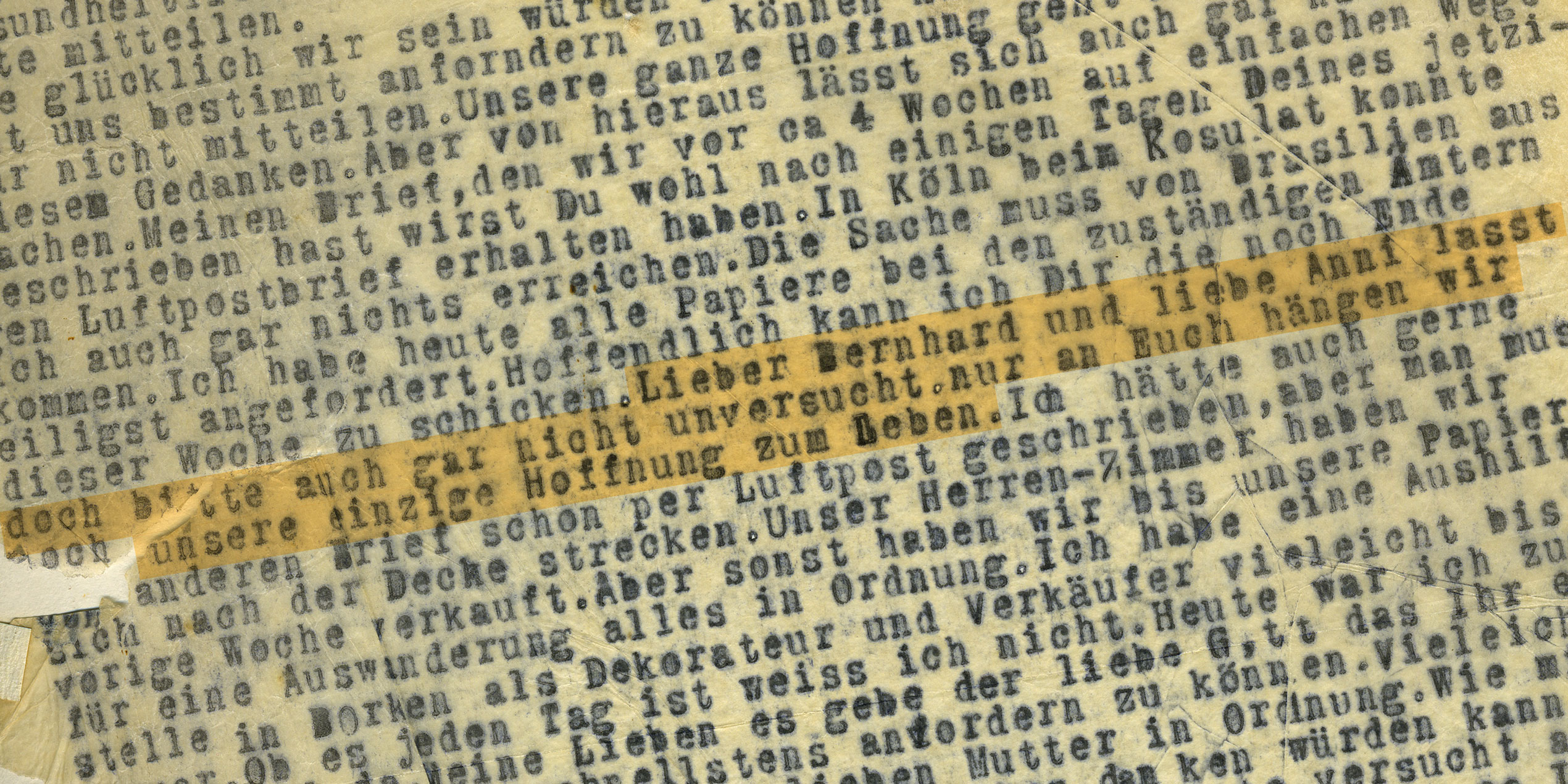

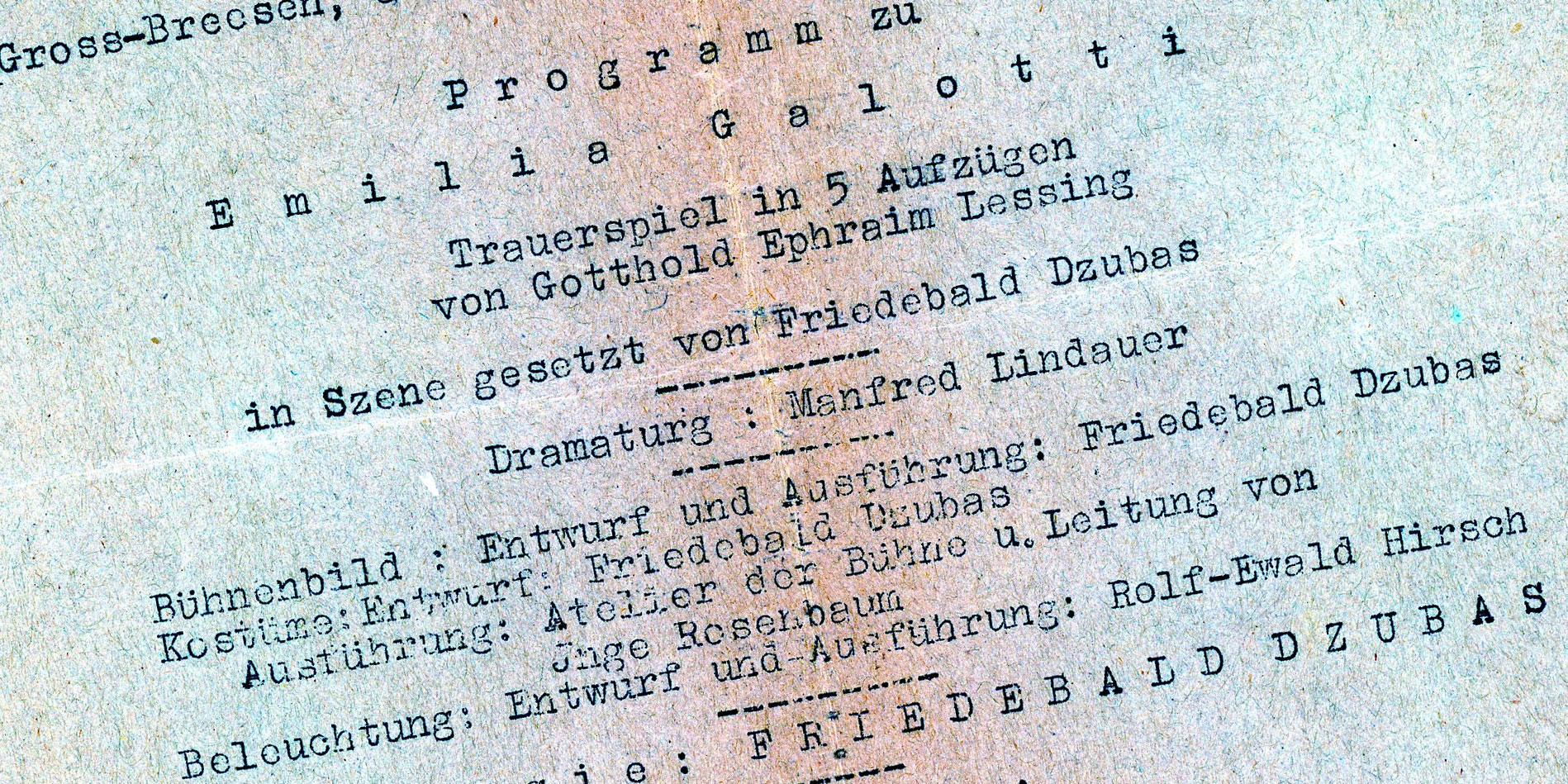

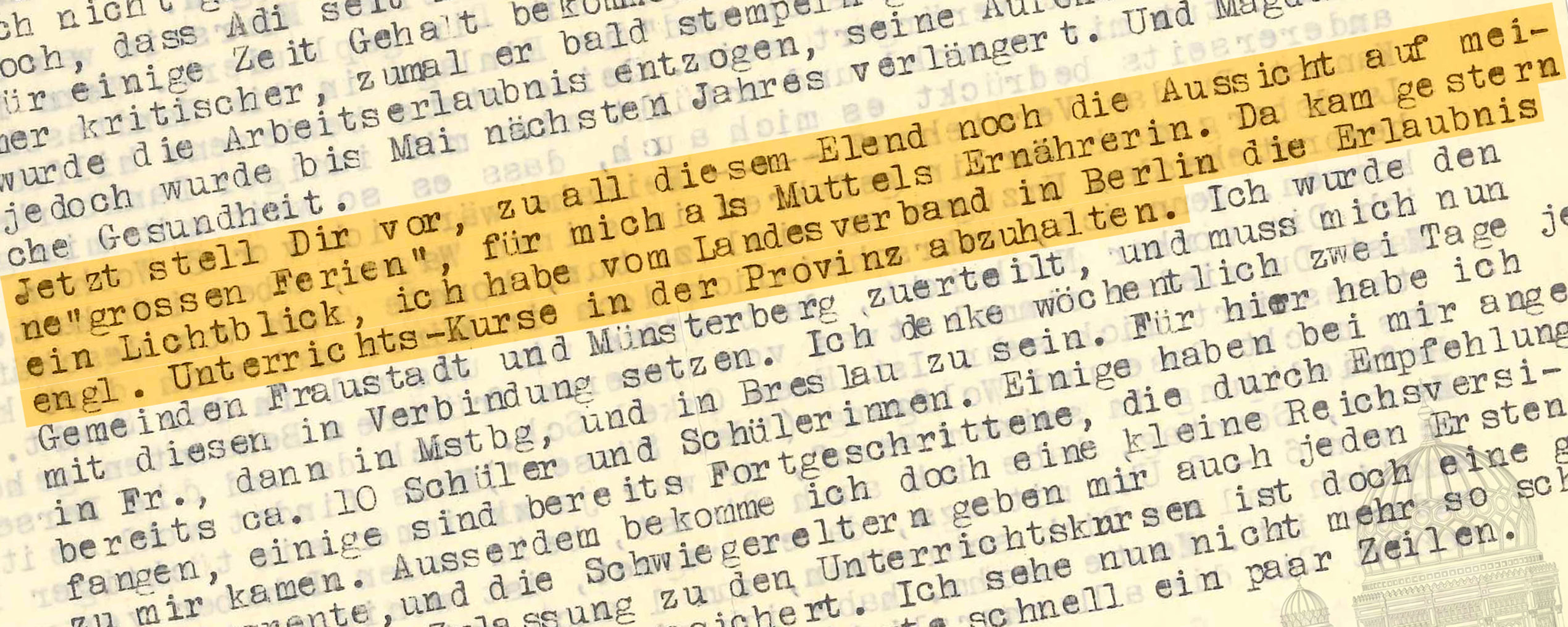

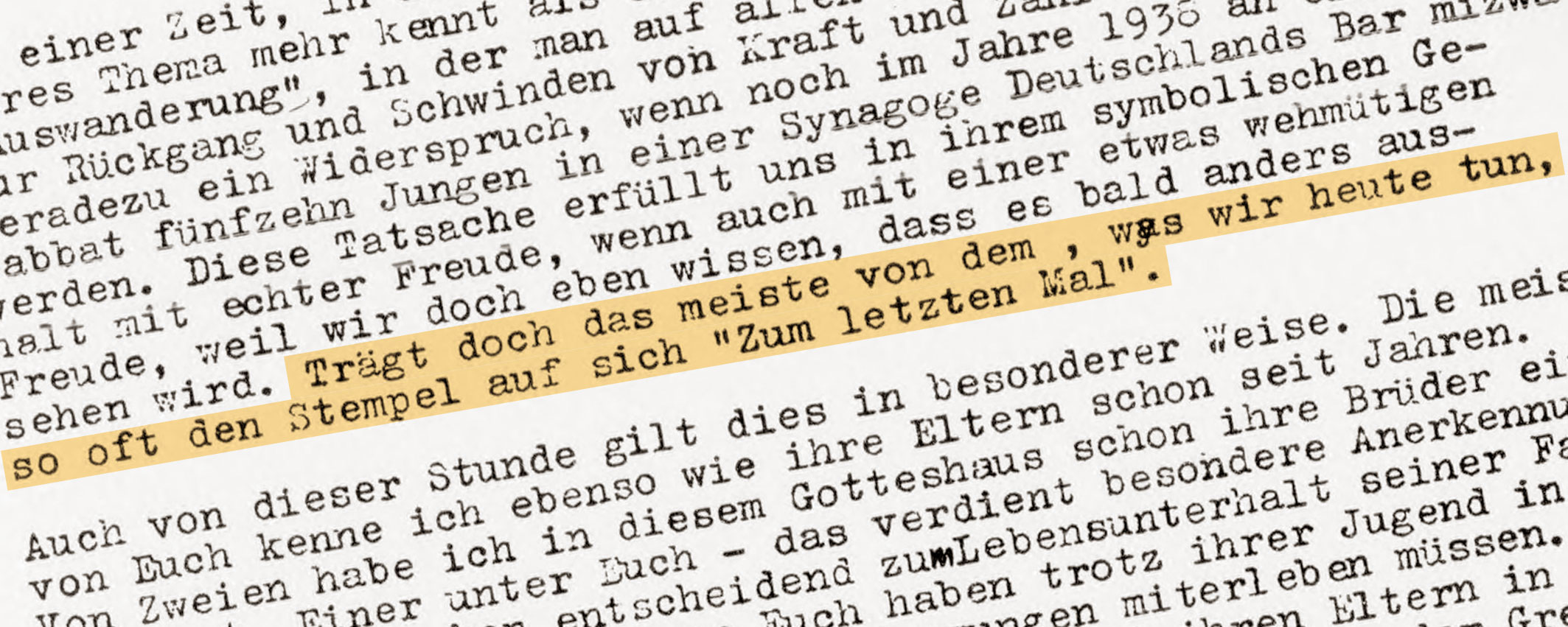

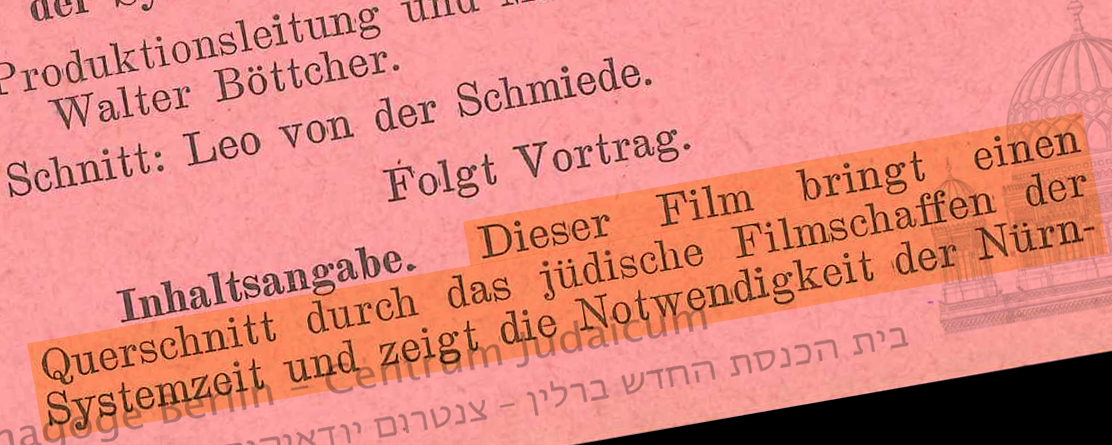

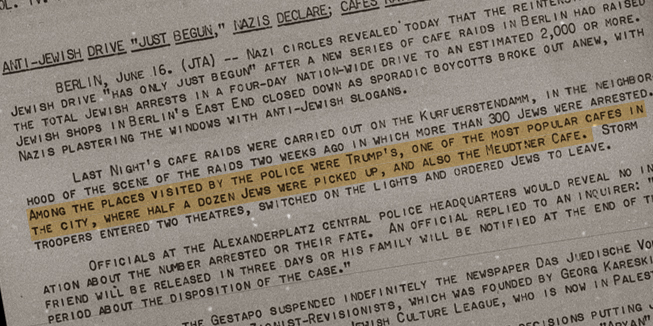

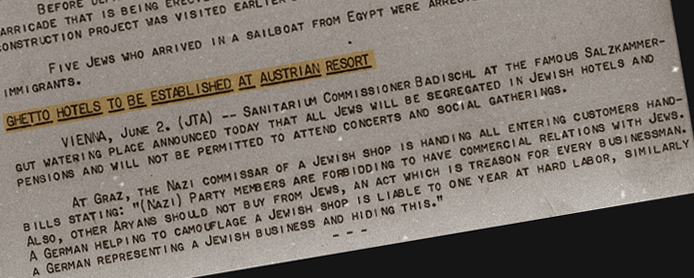

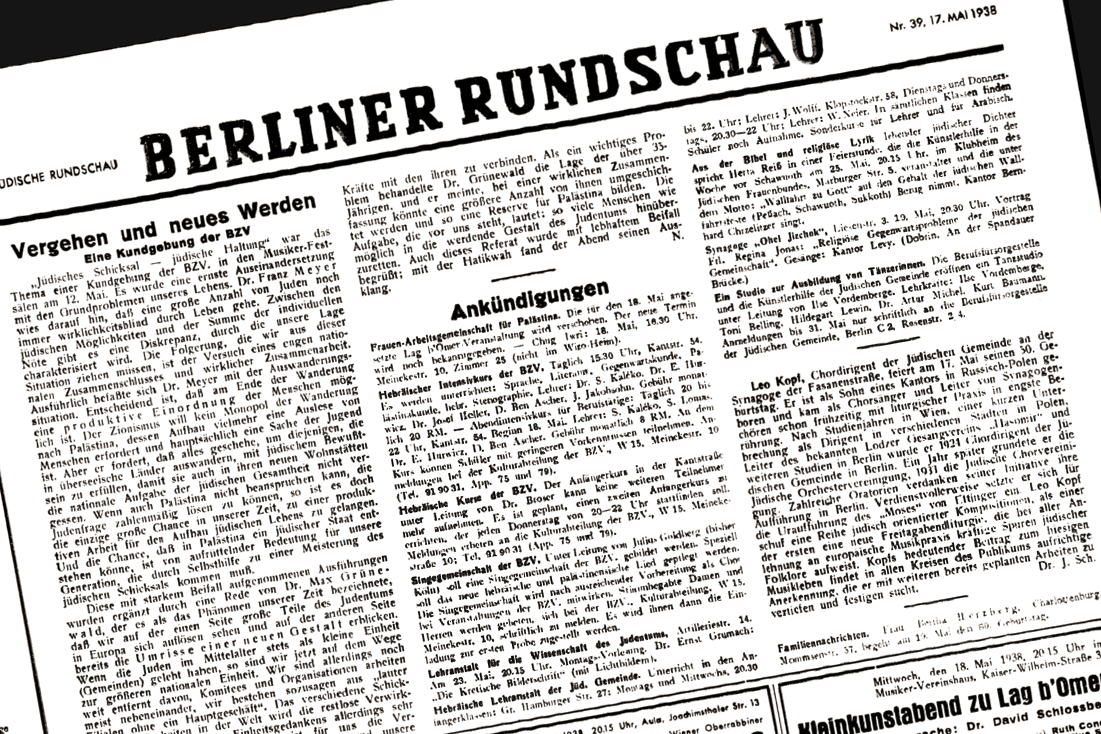

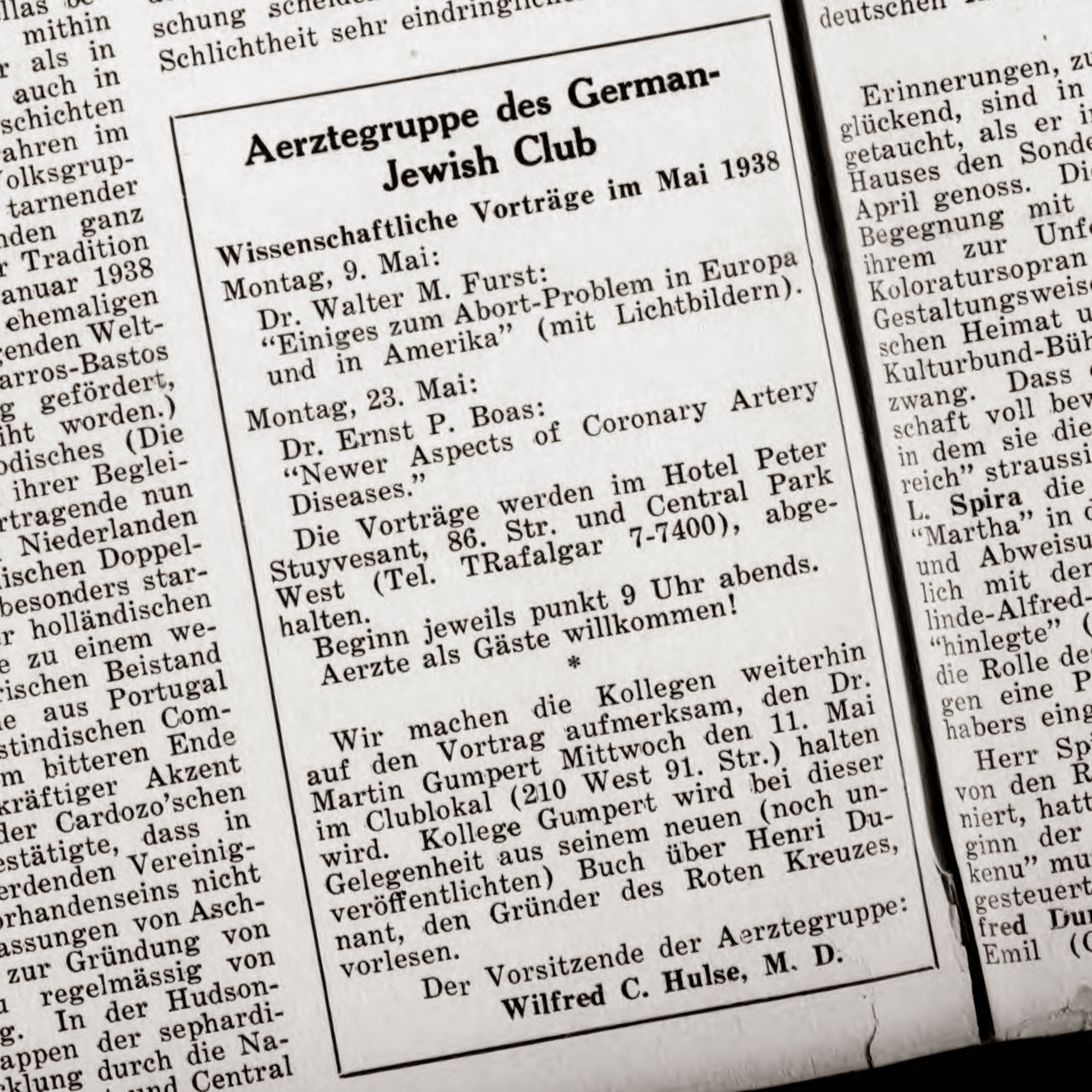

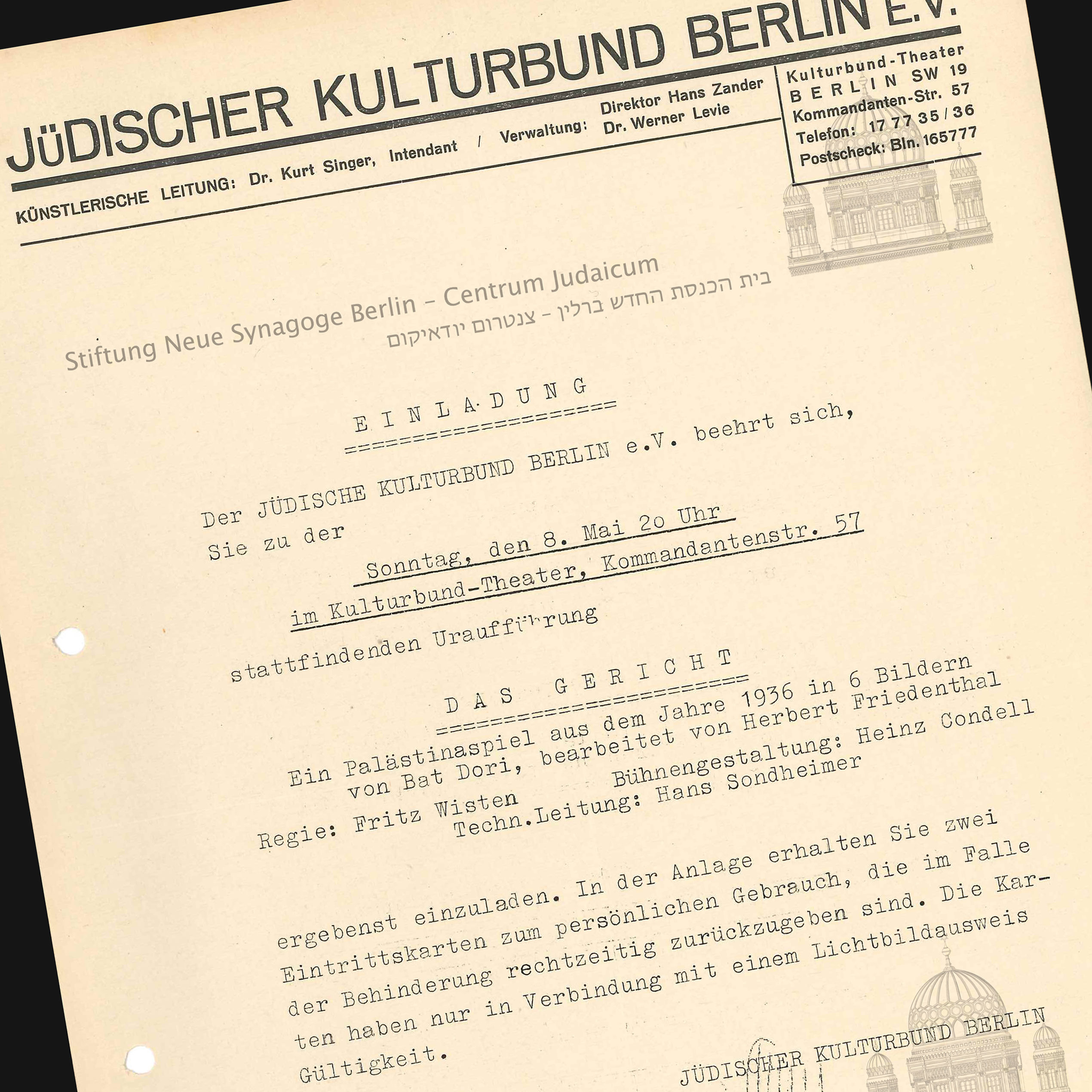

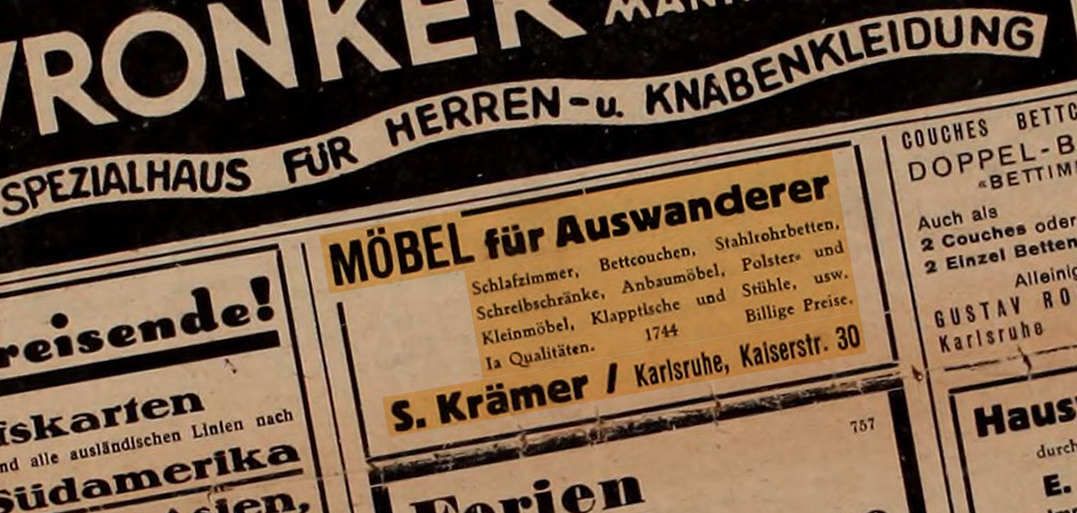

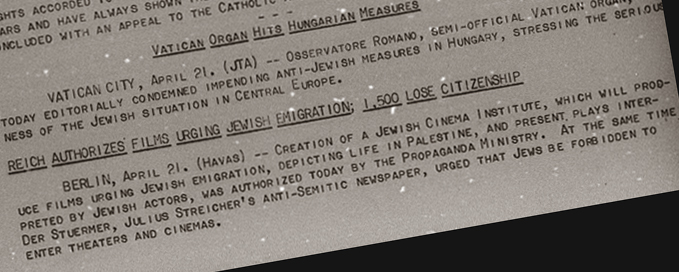

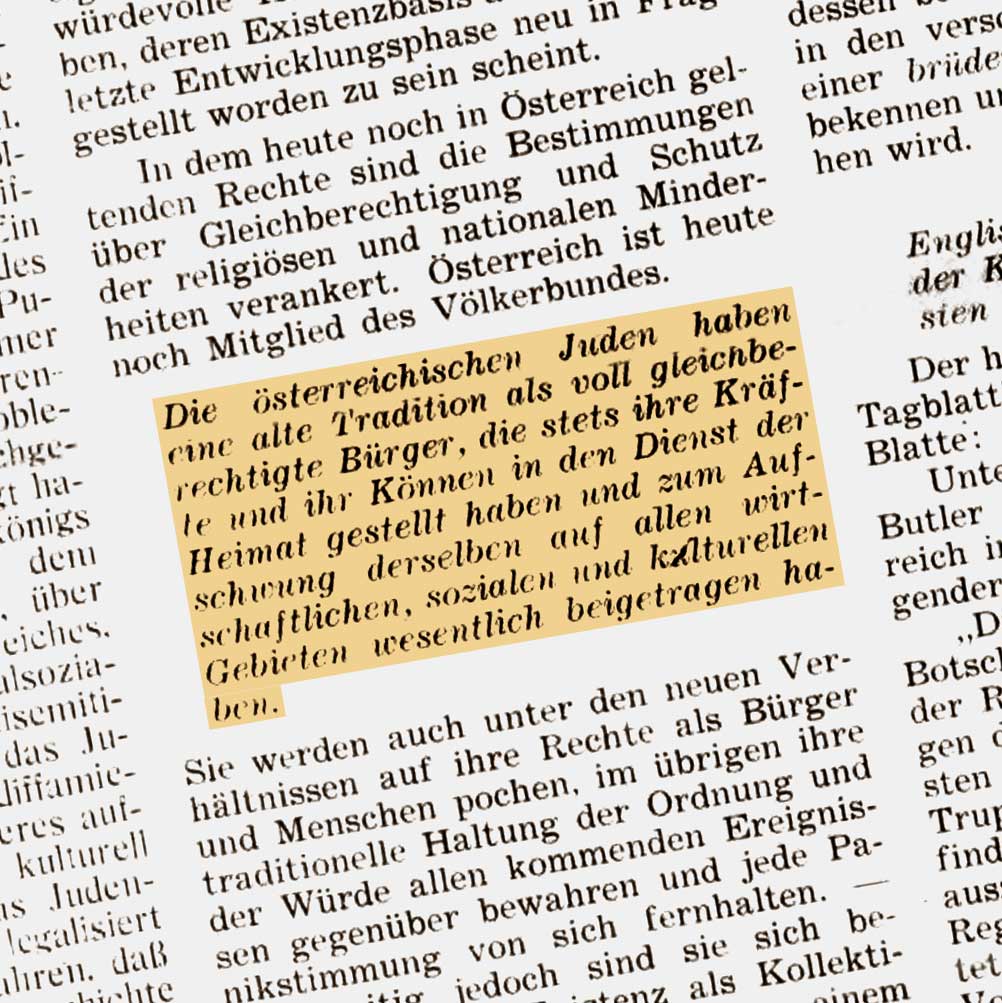

The banishment of Jews from public spaces was far advanced by now. Already in 1933, Jewish creative artists had been dismissed from state-sponsored cultural life. Since November 12th, 1938, Jews were no longer admitted even as audience members at “presentations of German culture” and were banished from concert halls, opera houses, libraries and museums. More and more restaurants and shops denied access to Jews. On Dec. 12th, 1938, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency pointed out a striking discrepancy: while abroad, the “German News Bureau,” the central news agency of the Reich which followed the directives of the Propaganda Ministry, spread the information that from January 1st, 1939, certain anti-Semitic measures would be relaxed, quite the opposite had been communicated to Jews inside the Reich. One fact, however, was not hidden: the goal was to prompt all Jews to emigrate, “also in the interest of the Jews themselves,” as the Bureau put it.

SOURCE

Institution:

Collection:

“News of Easing Anti-Jewish Curbs Not Published in Reich”

Source available in English

Chronology of major events in 1938

Aktion “Arbeitsscheu Reich”

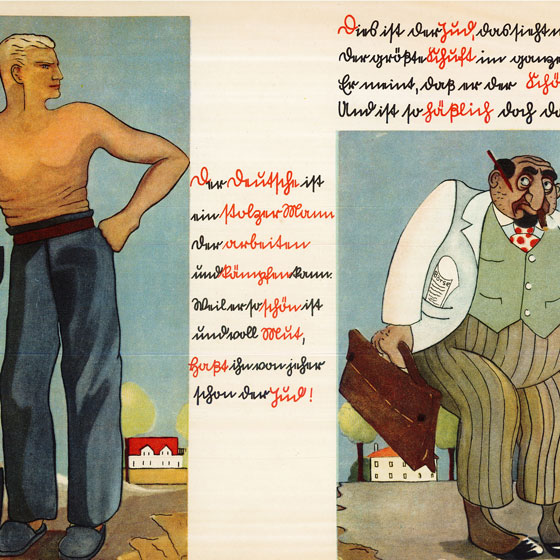

Poster for the Reich Labor Service, 1938.

Heinrich Himmler orders a “one-time, comprehensive, surprise attack” on Arbeitsscheue. This designation, which means “work-shy” or “indolent,” includes men of working age who have rejected two job offers or who quit after a short period of time. The Gestapo, the secret police force of the National Socialists, was tasked with the endeavor and collected the necessary information in collaboration with employment offices. From April 21 through April 30, between 1,500 and 2,000 men are arrested and brought to the concentration camp Buchenwald. Hearings are not scheduled to take place until the second half of the year.

View chronology of major events in 1938