Individual hakhsharah

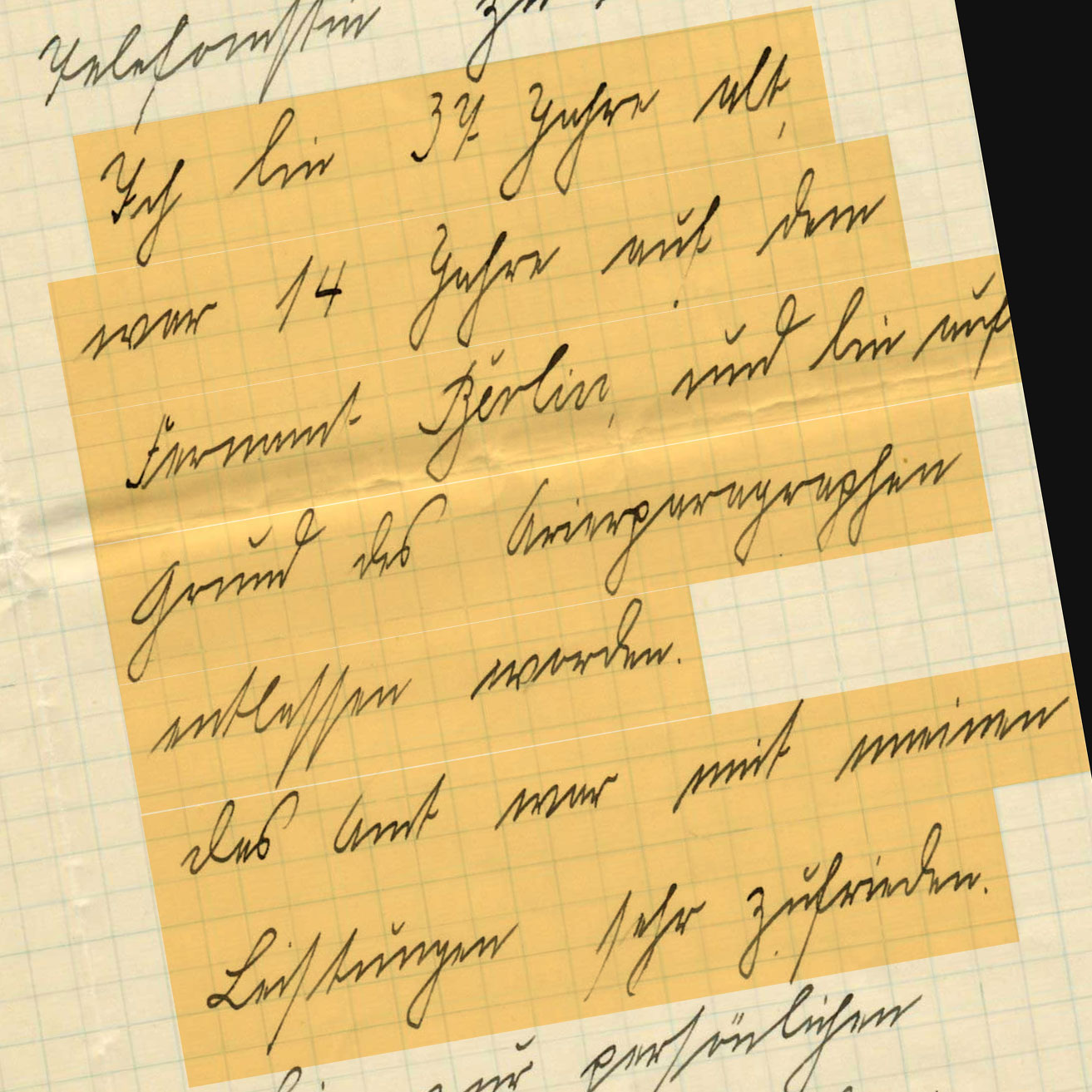

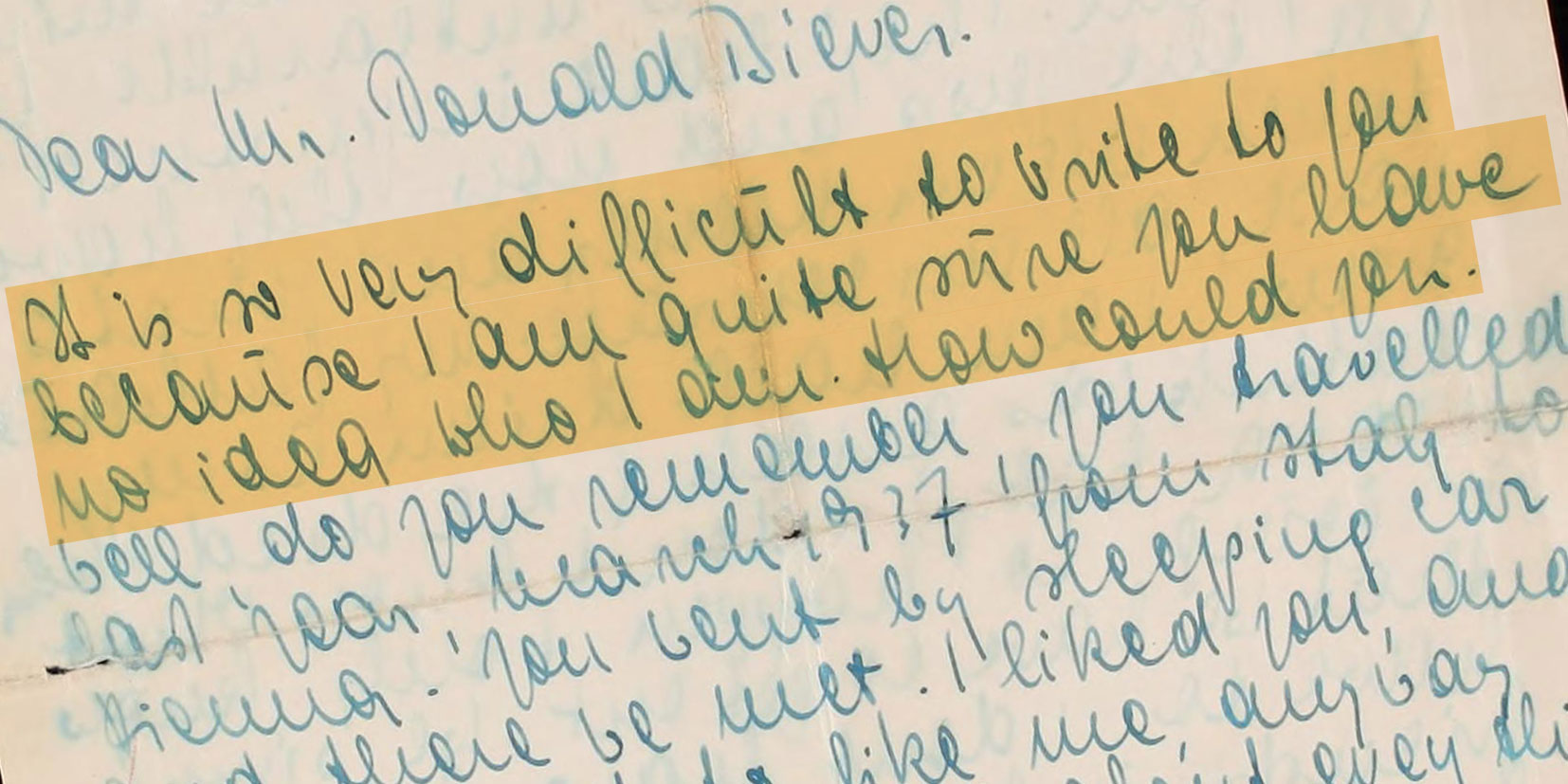

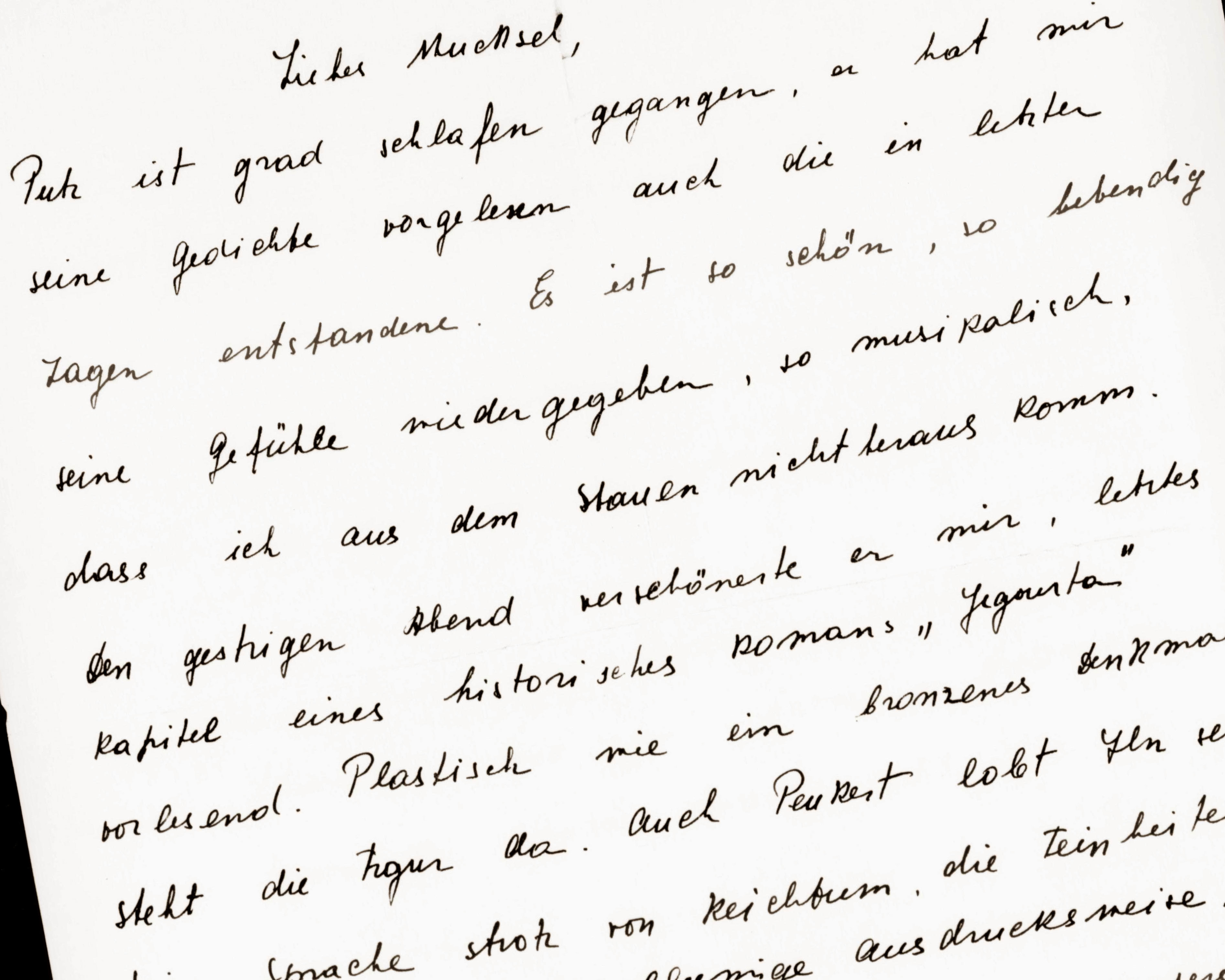

17-year-old Marianne suffers alone in England

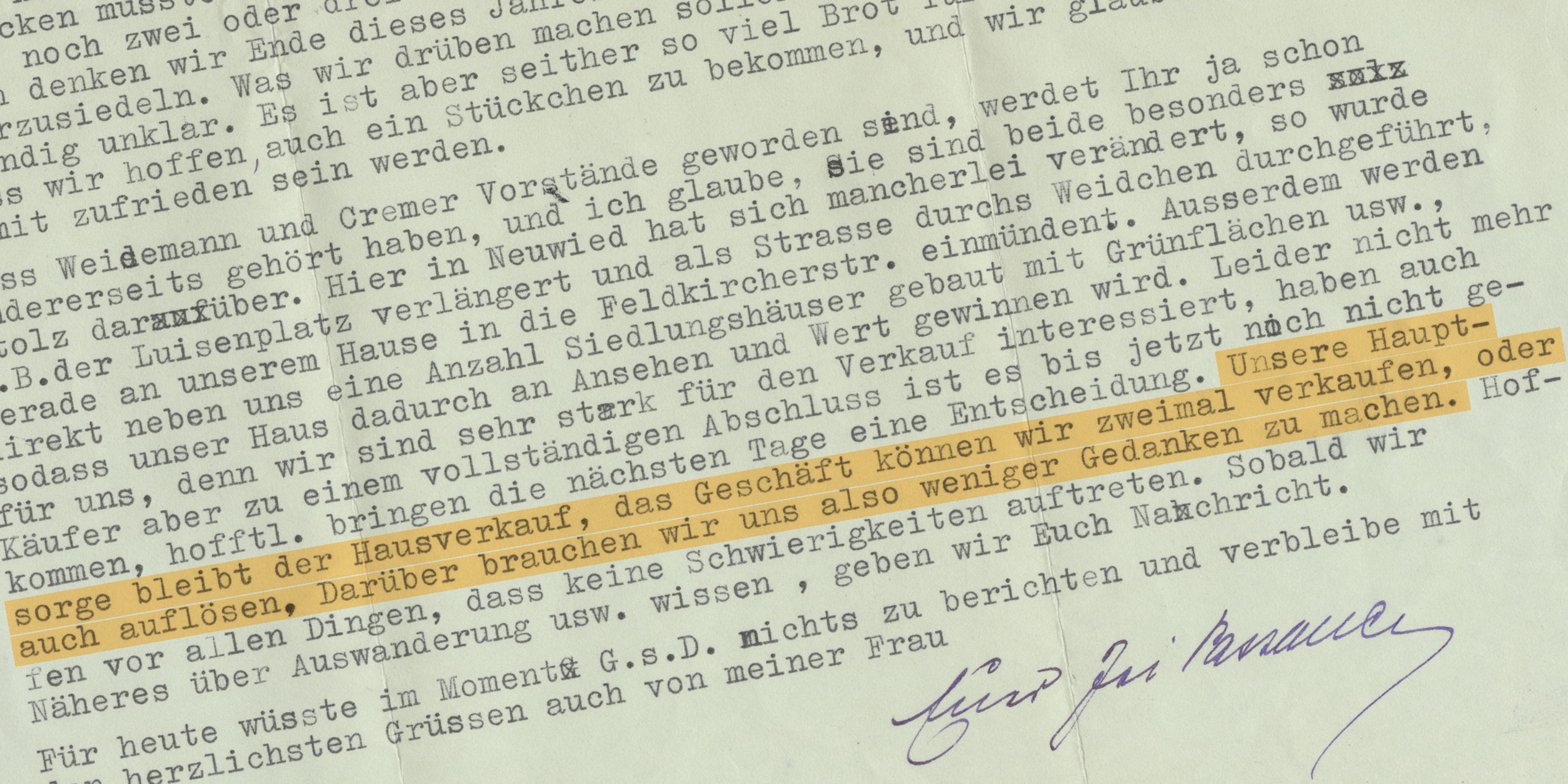

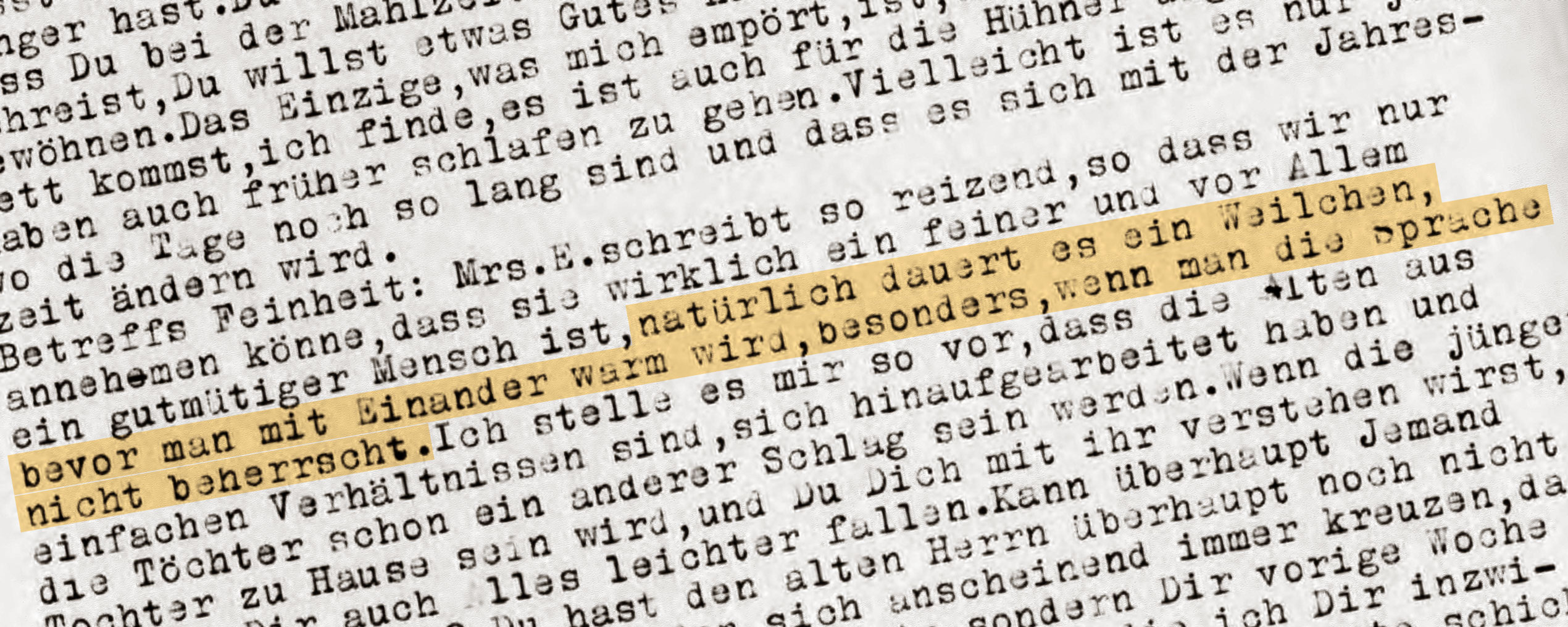

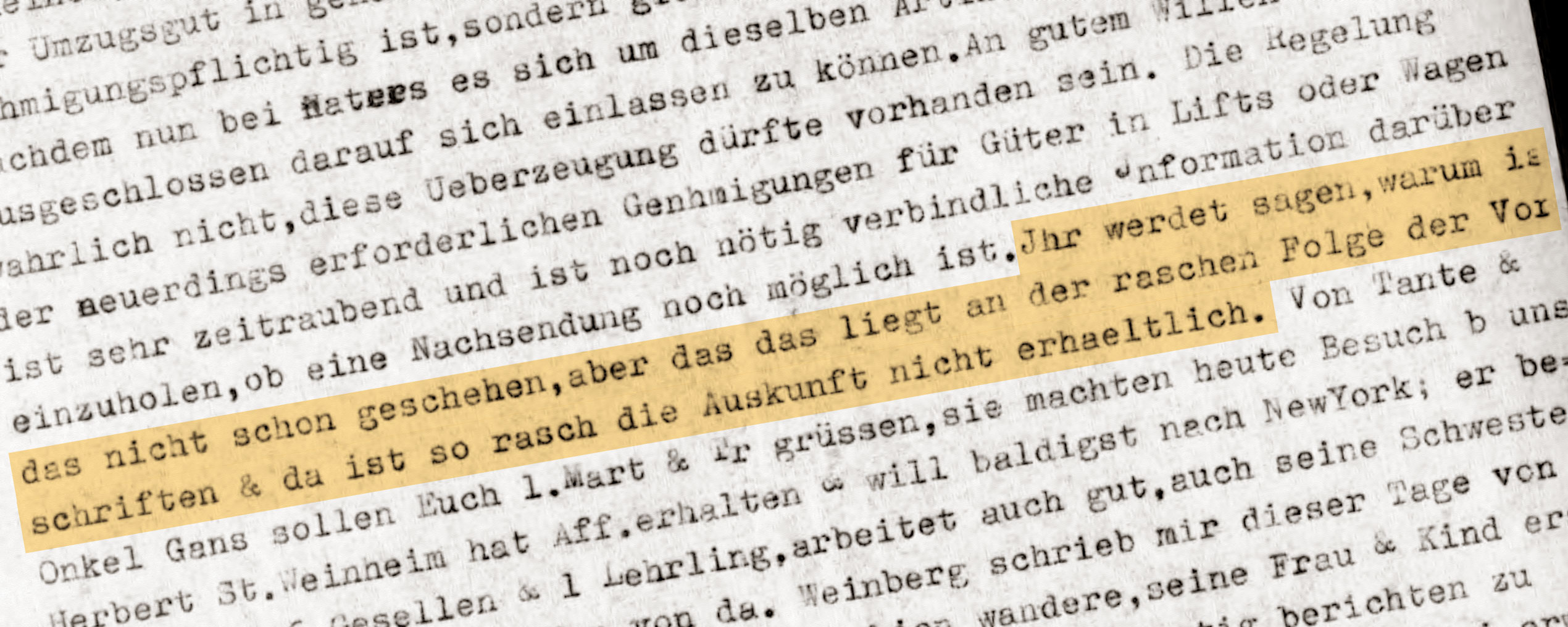

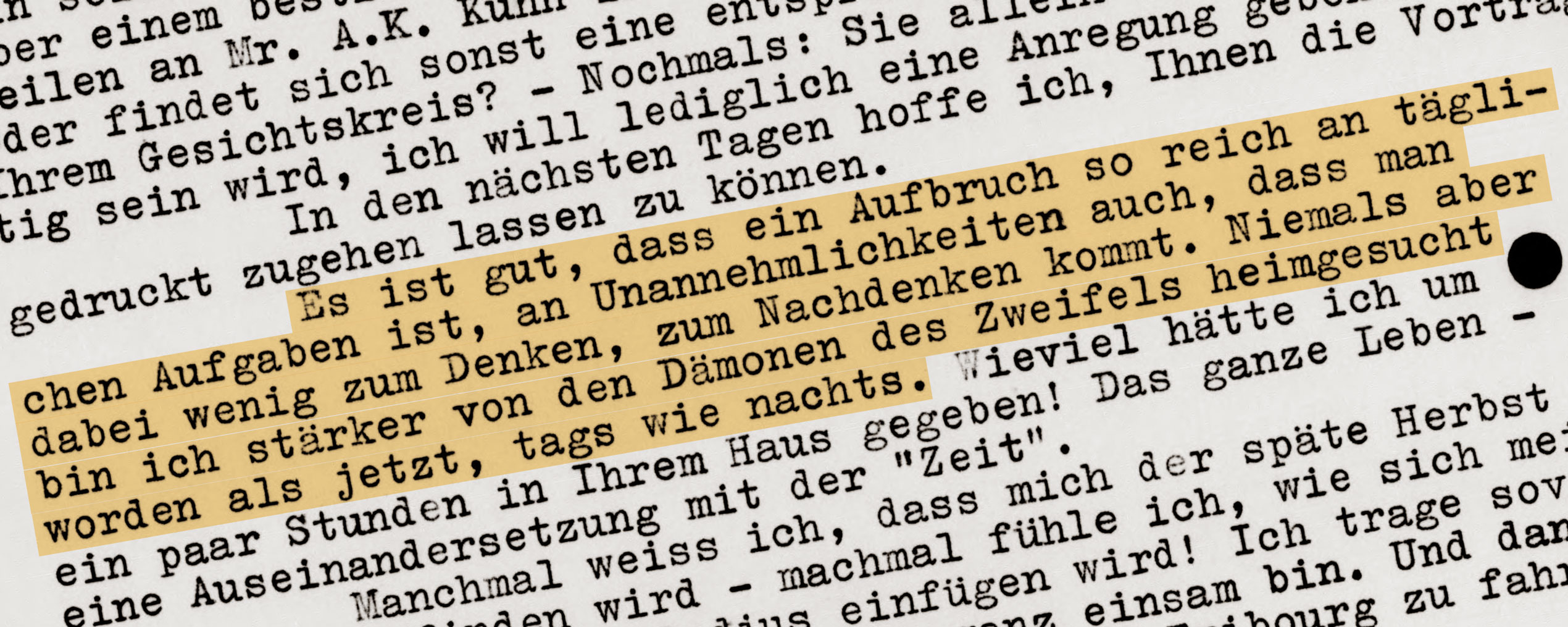

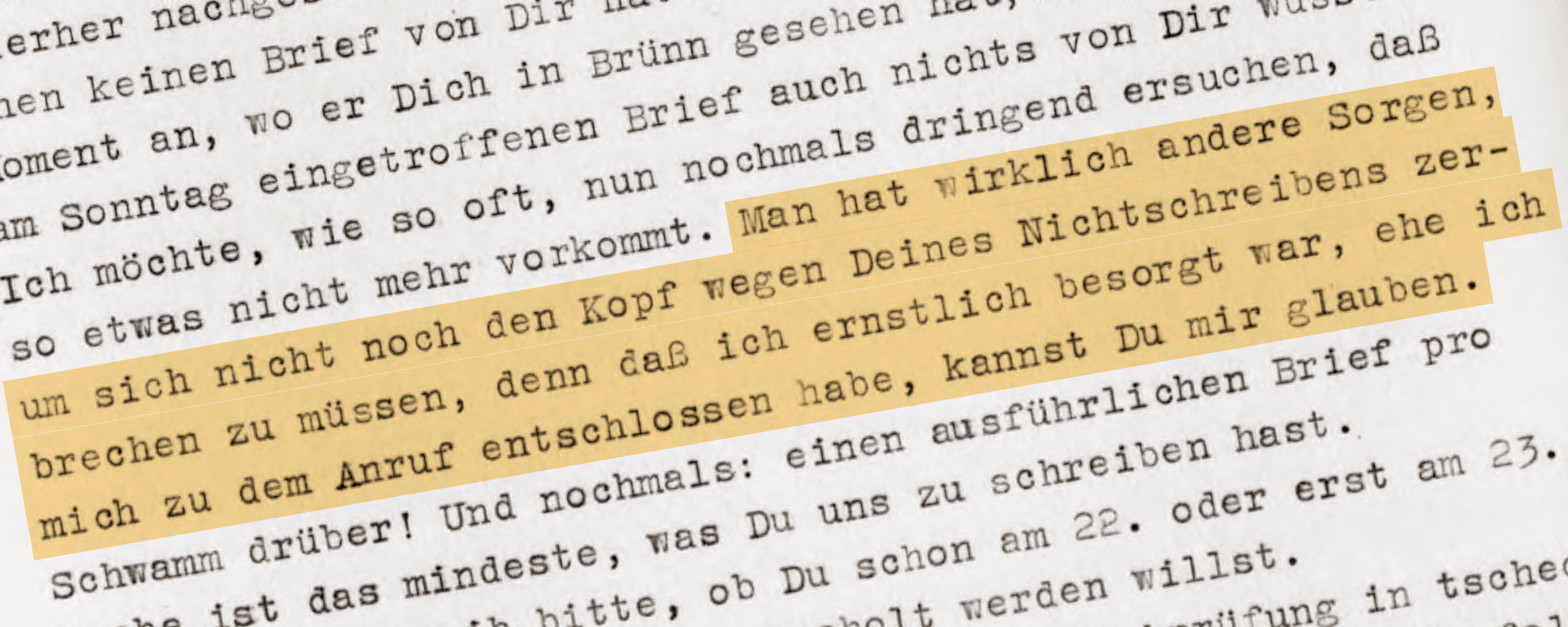

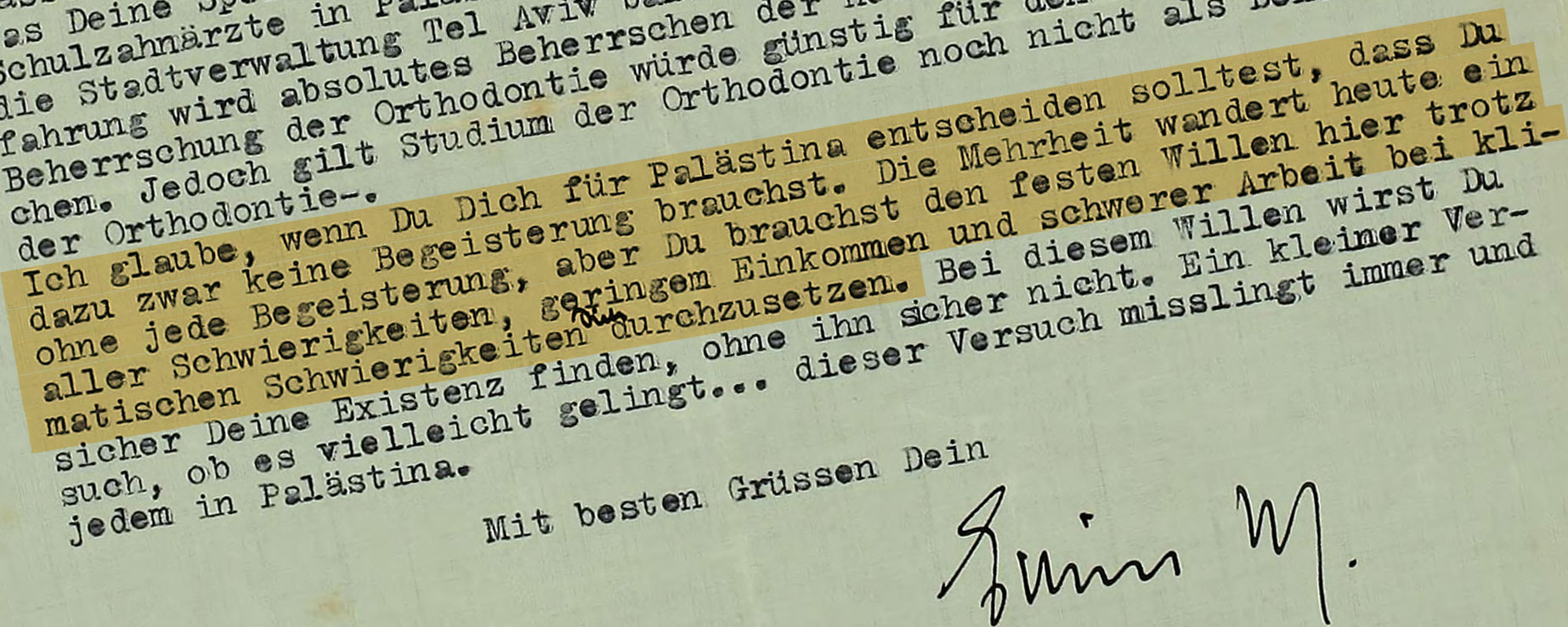

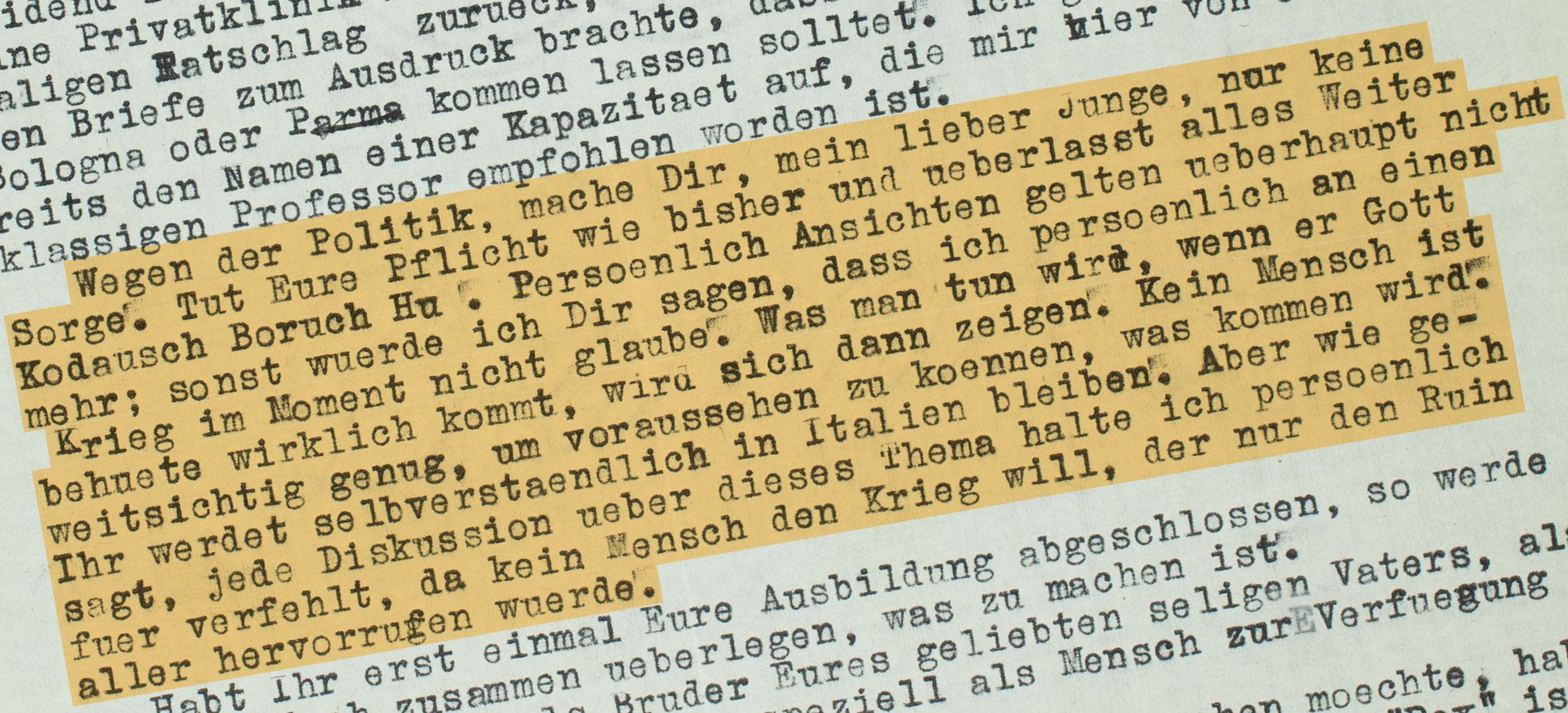

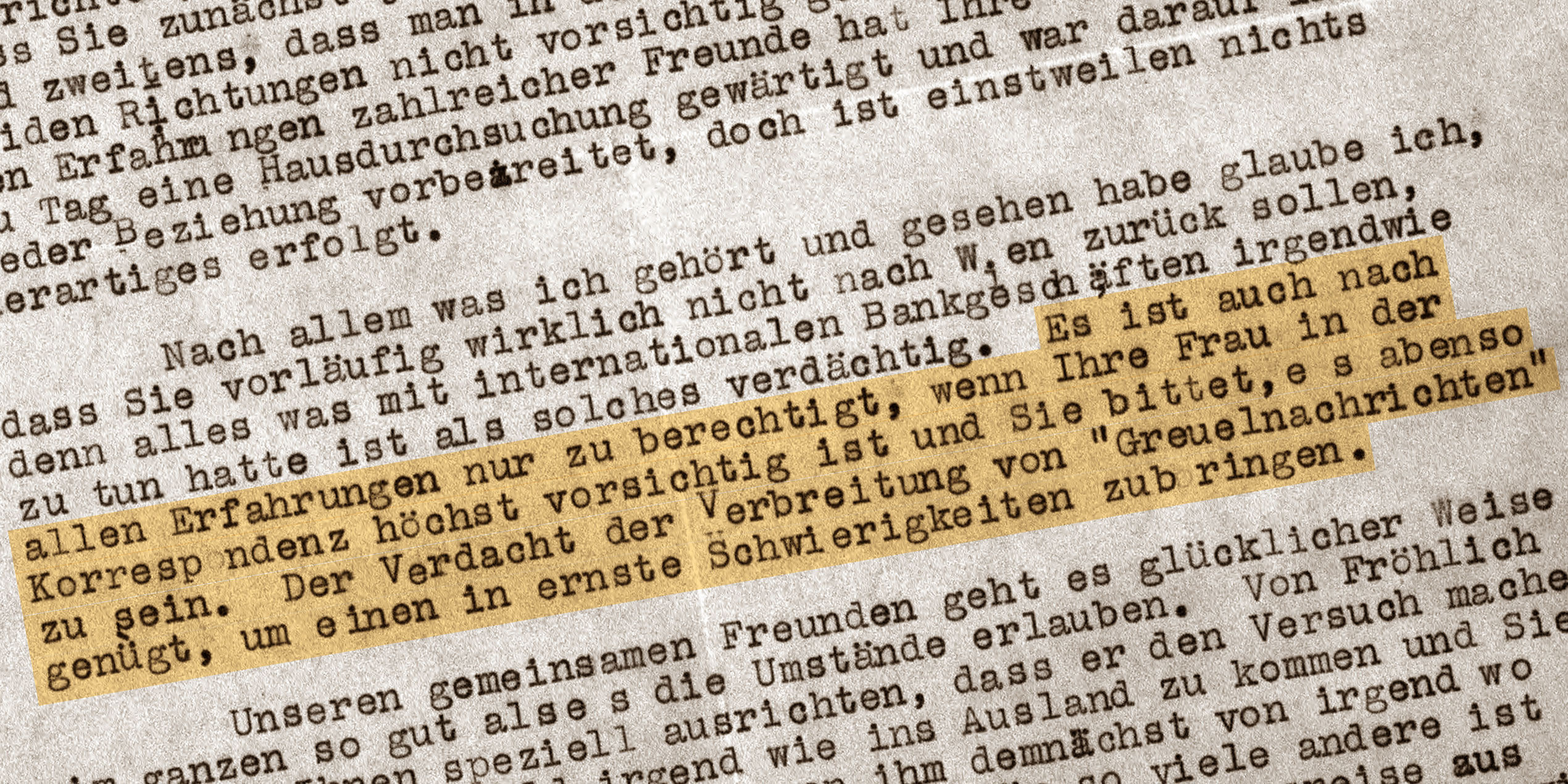

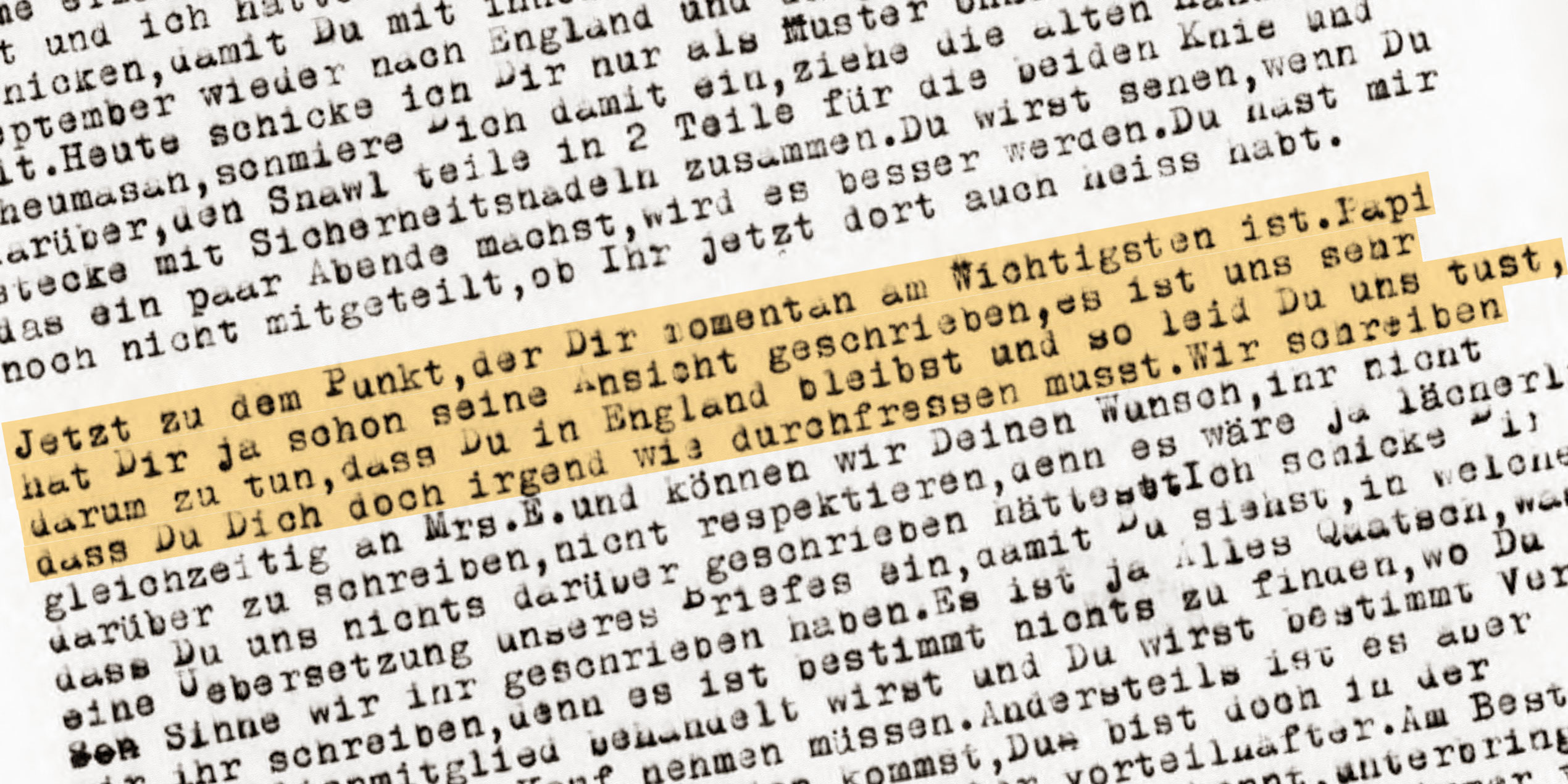

“And now to the point that is most important to you at the moment. Daddy has already written you his views, we are very much concerned that you stay in England, and much as we feel sorry for you, you'll have to get through this somehow.”

Teplitz

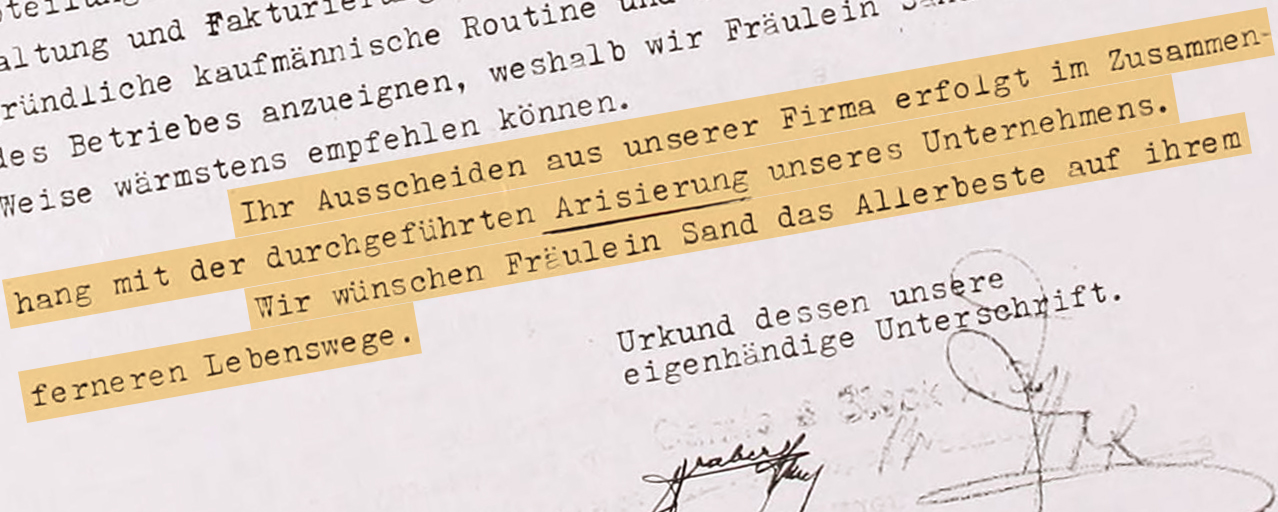

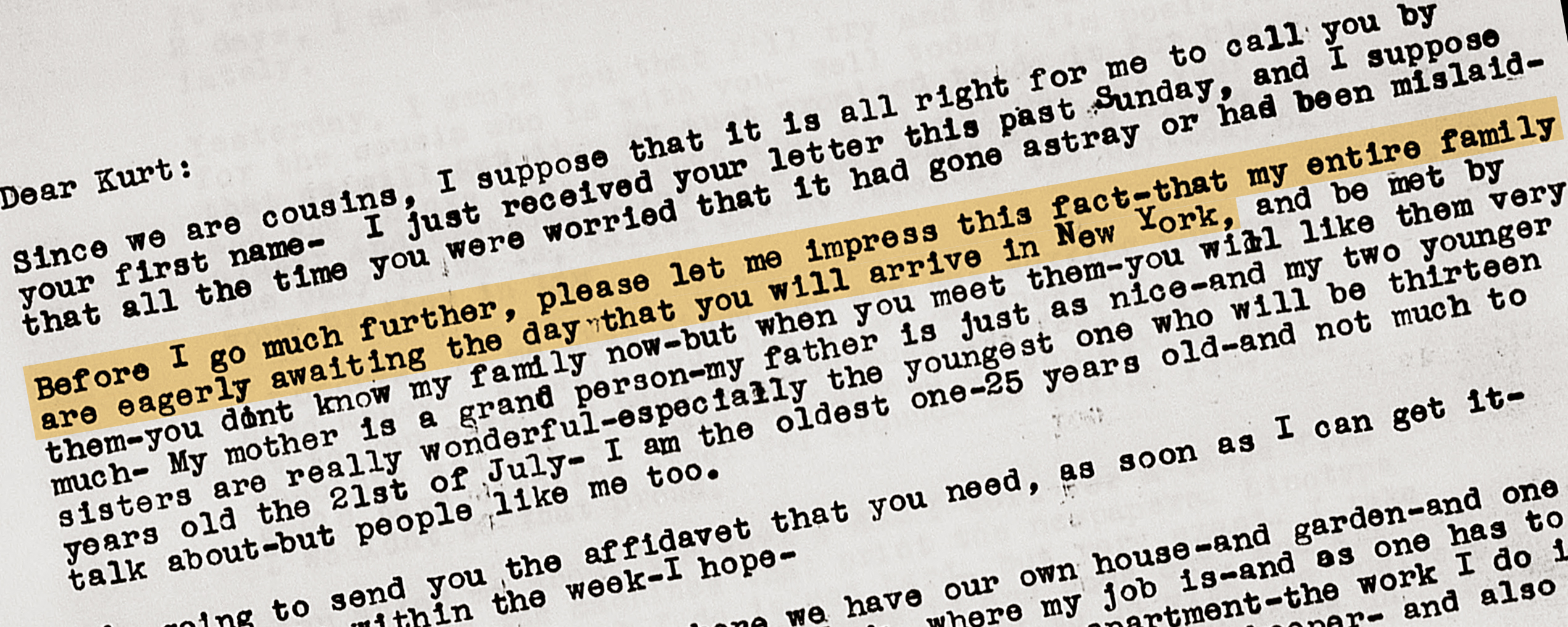

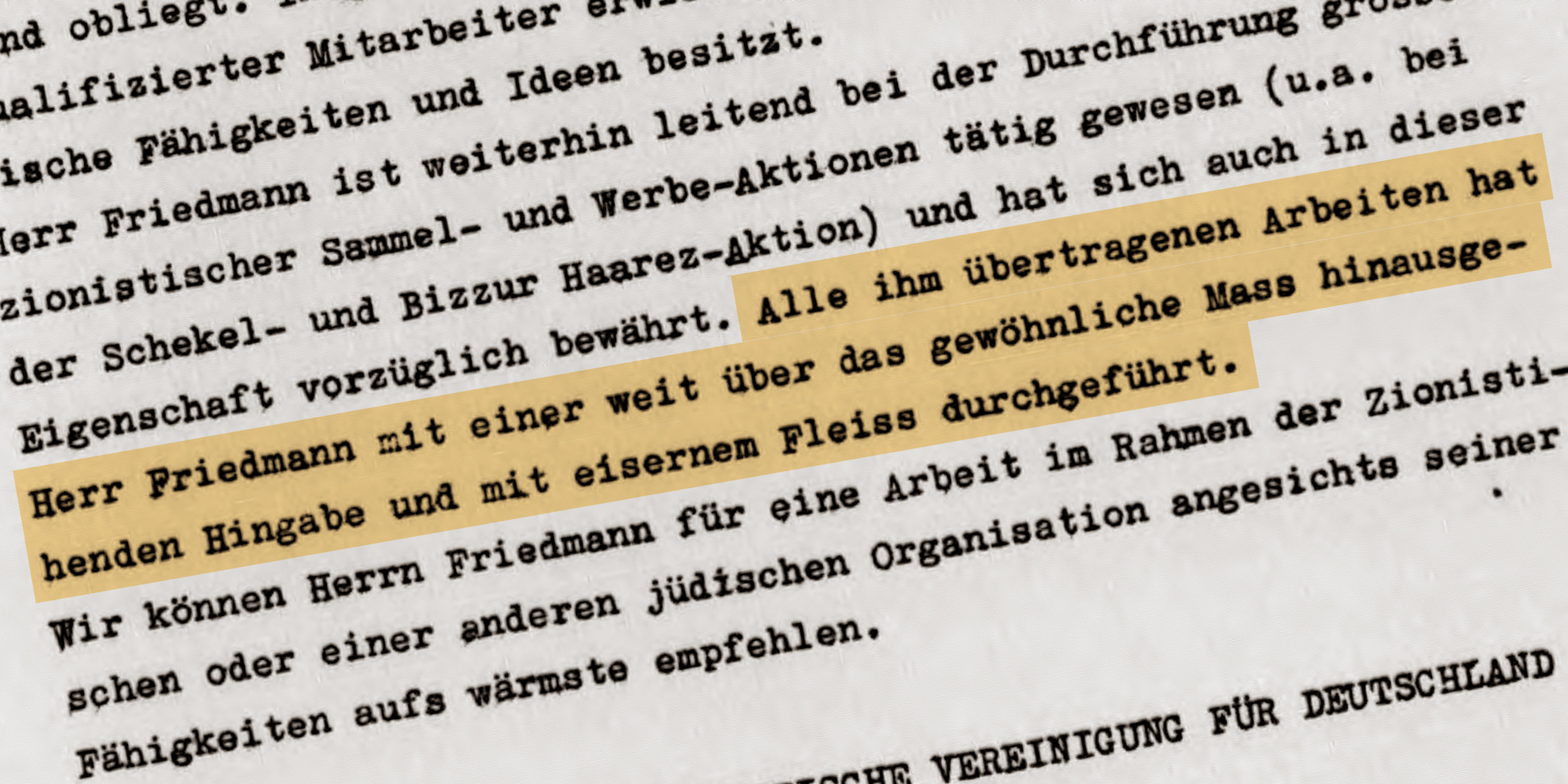

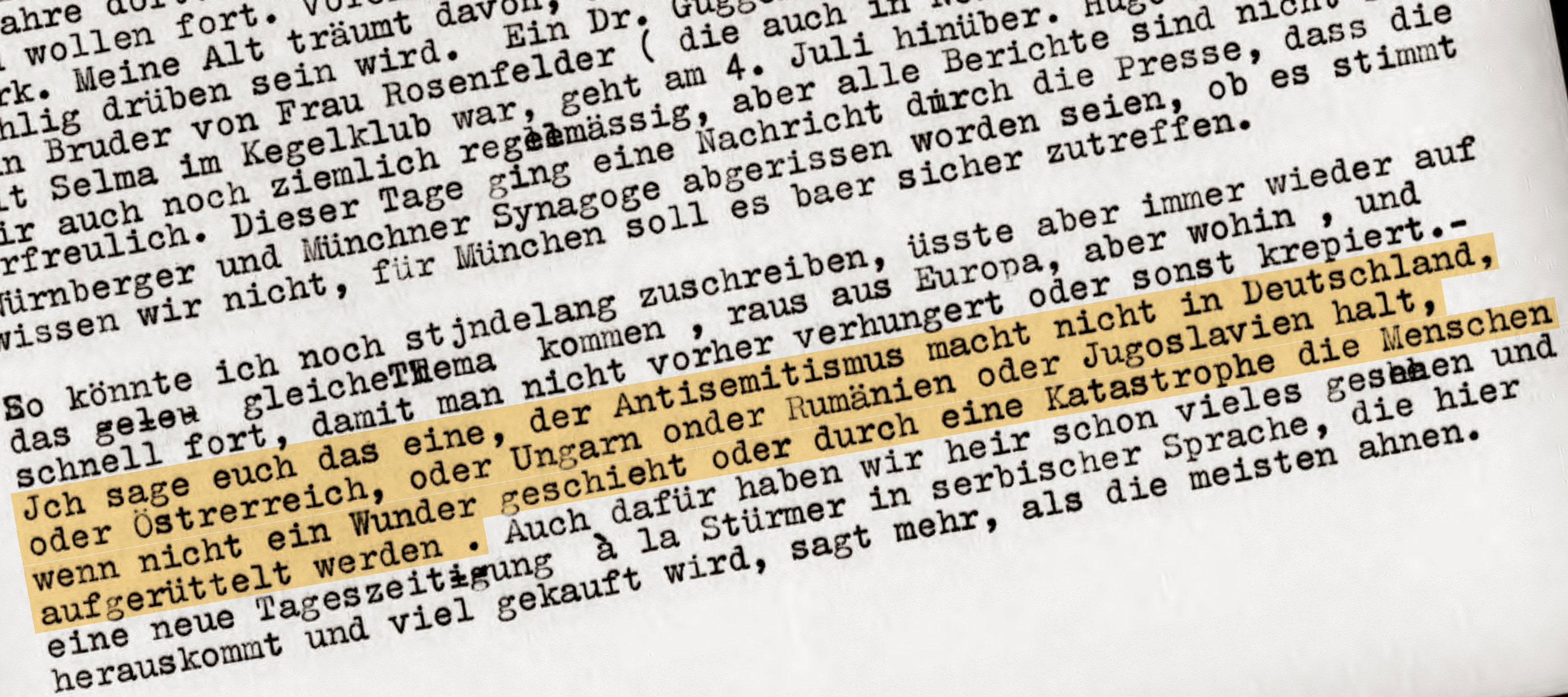

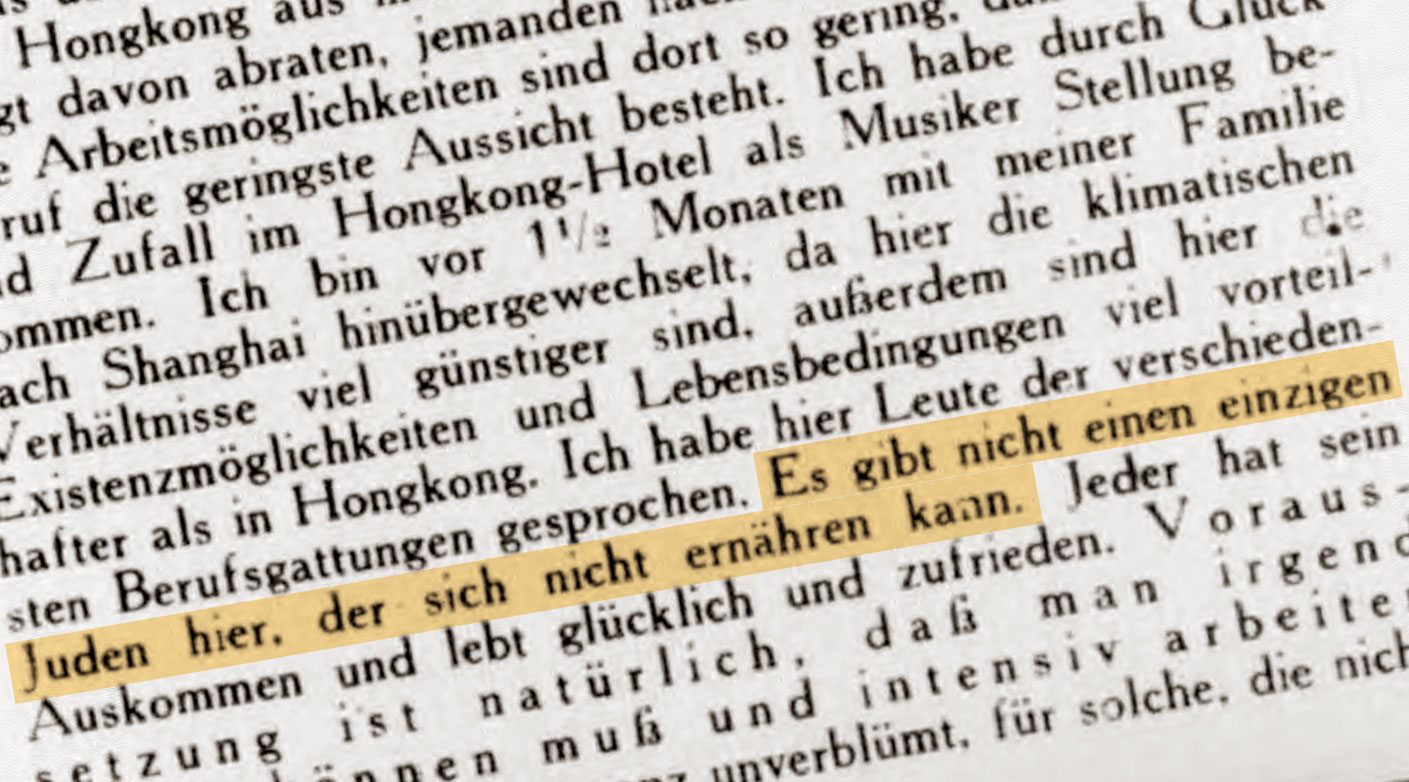

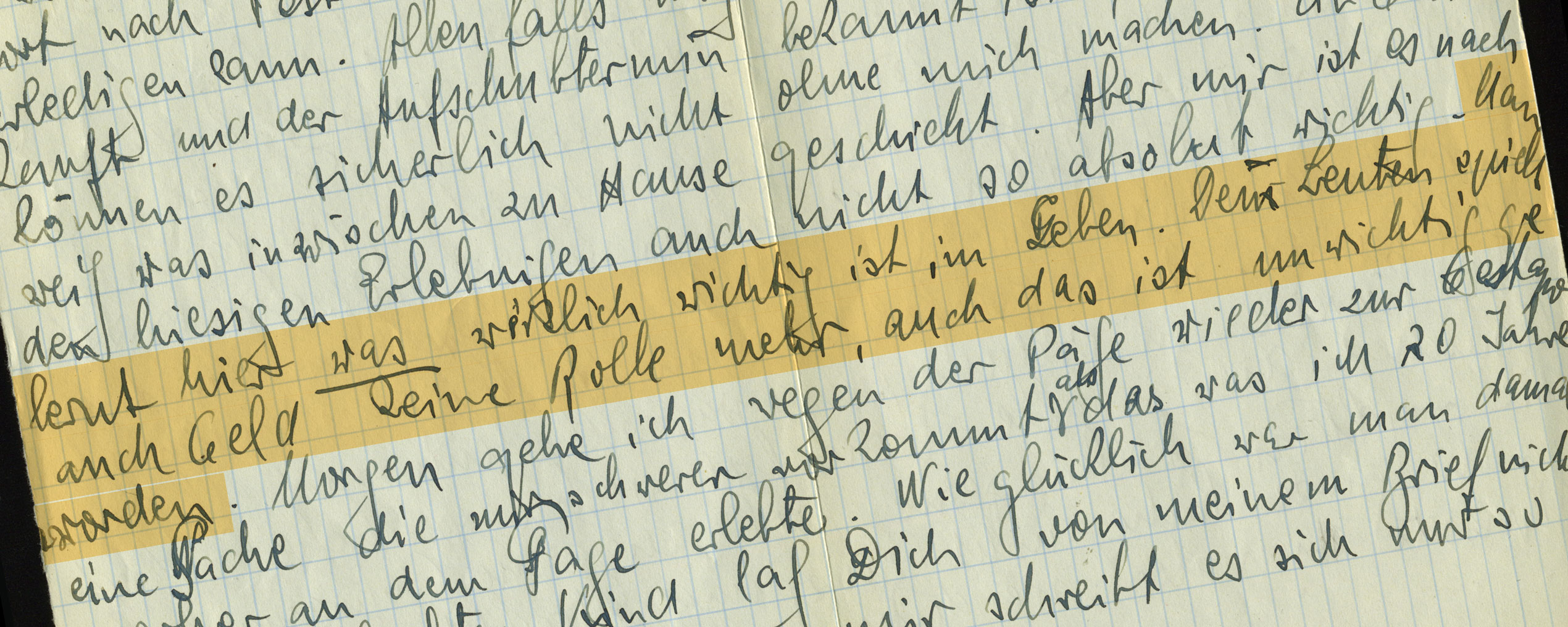

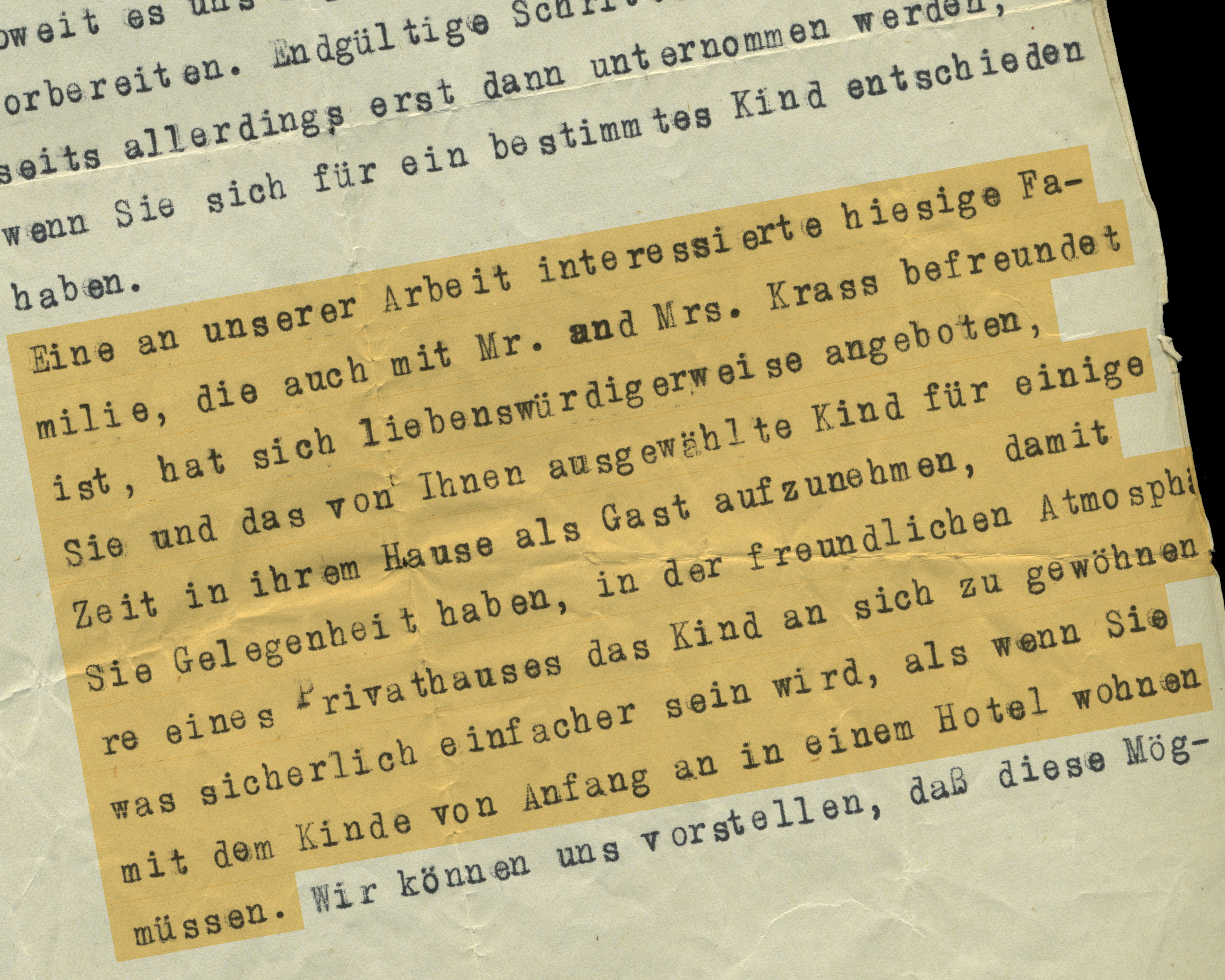

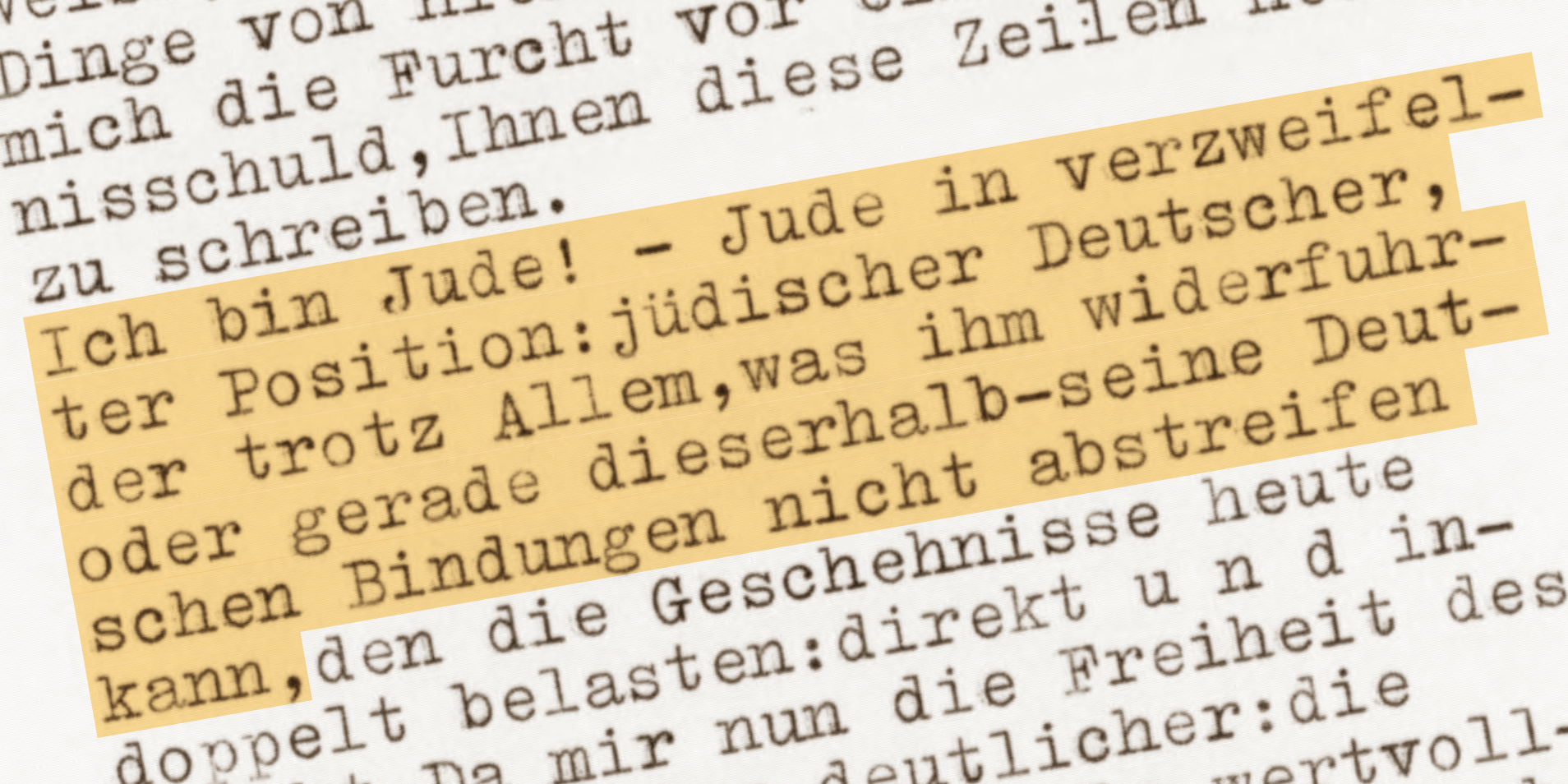

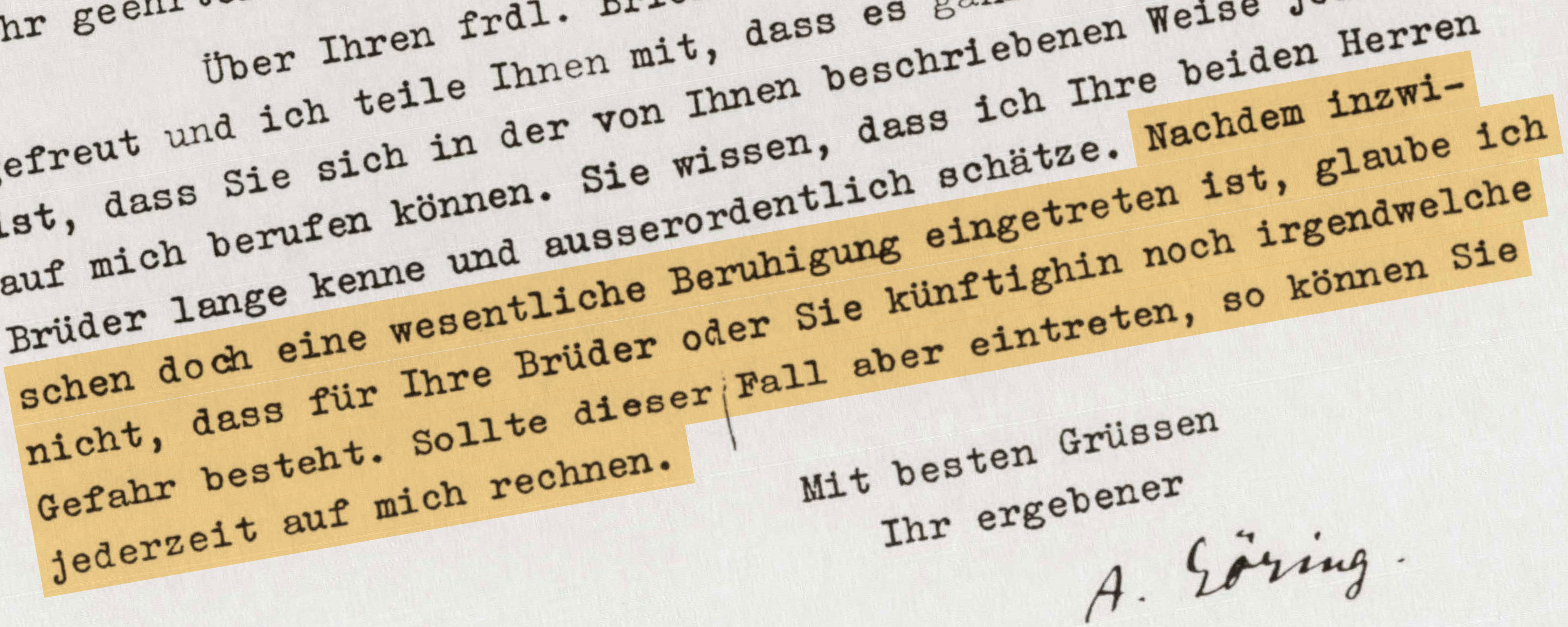

In July 1938, 17-year-old Marianne Pollak traveled all by herself from Teplitz/Teplice (Czechoslovakia) to England. Not accustomed to the climate there, the young girl developed rheumatism and was in generally miserable condition. Every few days, her mother wrote her caring, supportive letters. While clearly vexed by Marianne’s unhappiness, Mrs. Pollak and her husband made sure to communicate to her the importance of her staying in England. Apparently, Marianne was in an individual hakhsharah program, meaning that she was acquiring skills preparing her for pioneer life in Palestine. In Eastern Europe, the Zionist Pioneer organization “HeChalutz” (“The Pioneer”) had been offering agricultural and other training courses for prospective settlers in pre-state Palestine since the late 19th century. A German branch was established in 1923, but the concept gained traction in western Europe only during the Great Depression and had its broadest reach during the years of persecution by the Nazis. Instead of being prepared collectively on farms, youngsters could also get their training individually, as seems to have been the case with Marianne.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

John Peters Pinkus Family Collection, AR 25520

Original:

Box 2, folder 22