Emigration as a condition for release

Freedom only after emigration

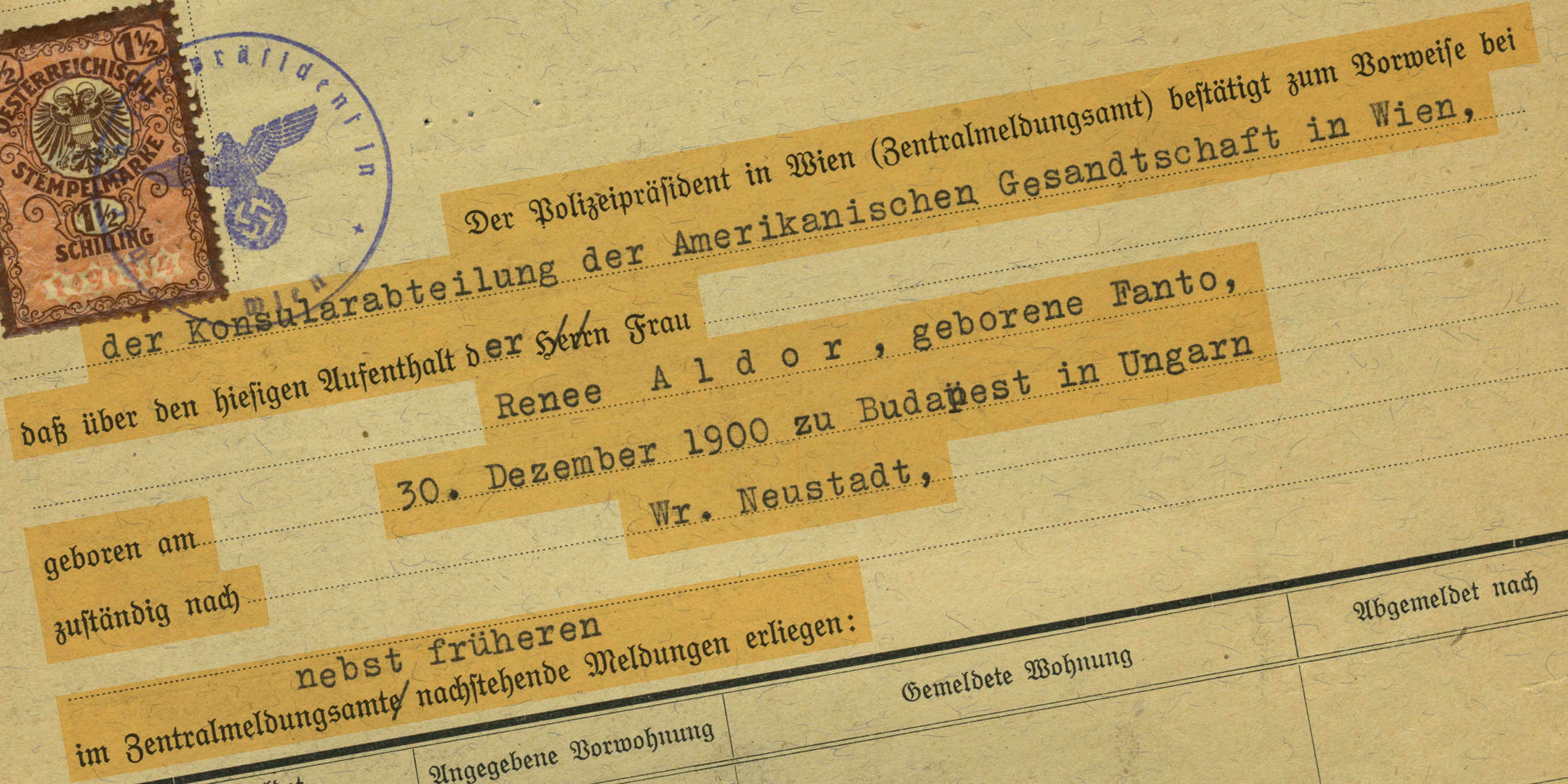

“For presentation at the consular section of the US Embassy in Vienna, the Chief of Police in Vienna (Central Registry Office) confirms that the following information is available regarding the sojourn here of Mrs. Renee Aldor, née Fanto, b. December 30 in Budapest, Hungary, right of residence in Wr. Neustadt, at the Central Registry Office.”

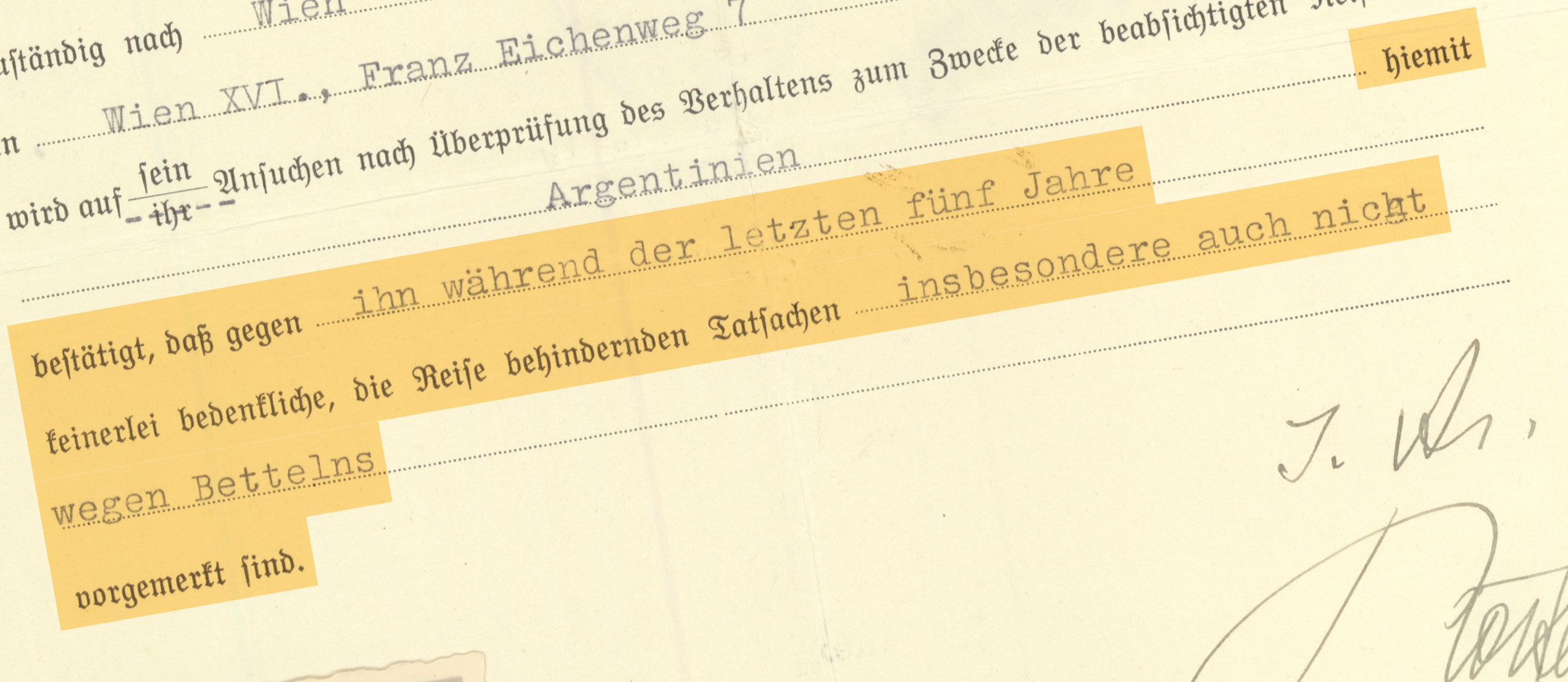

Vienna

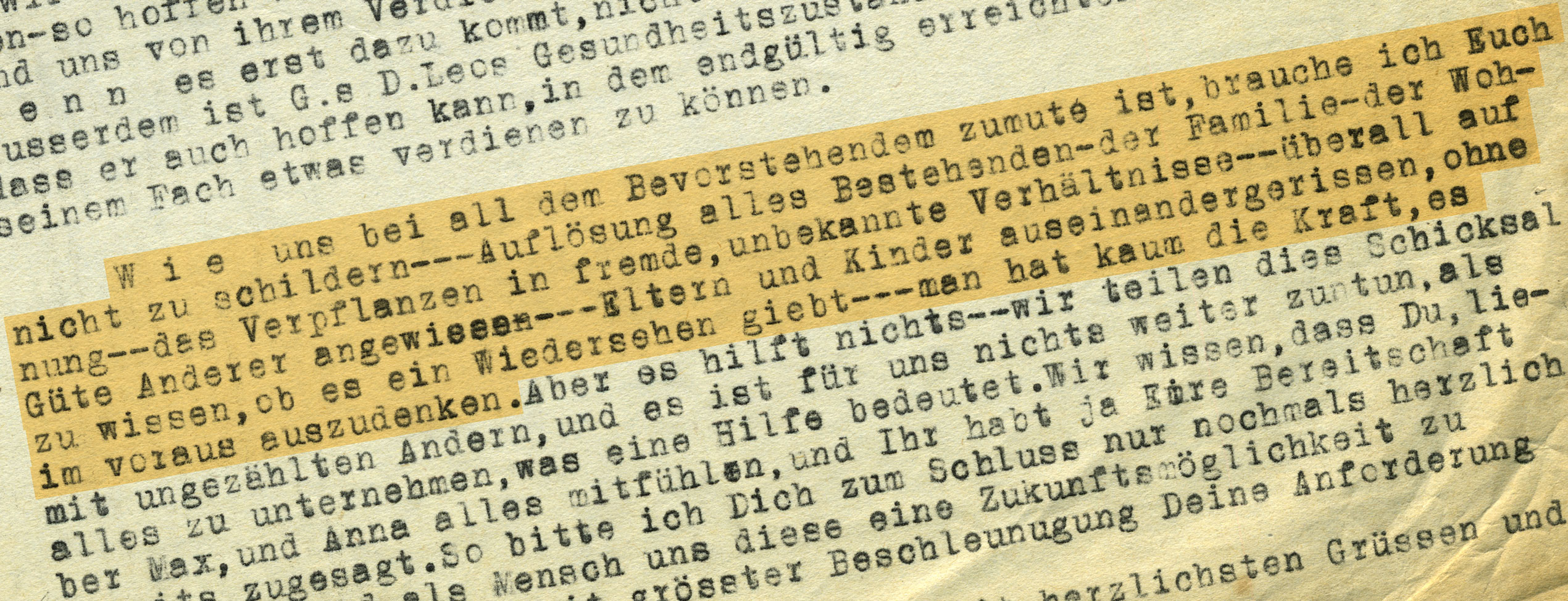

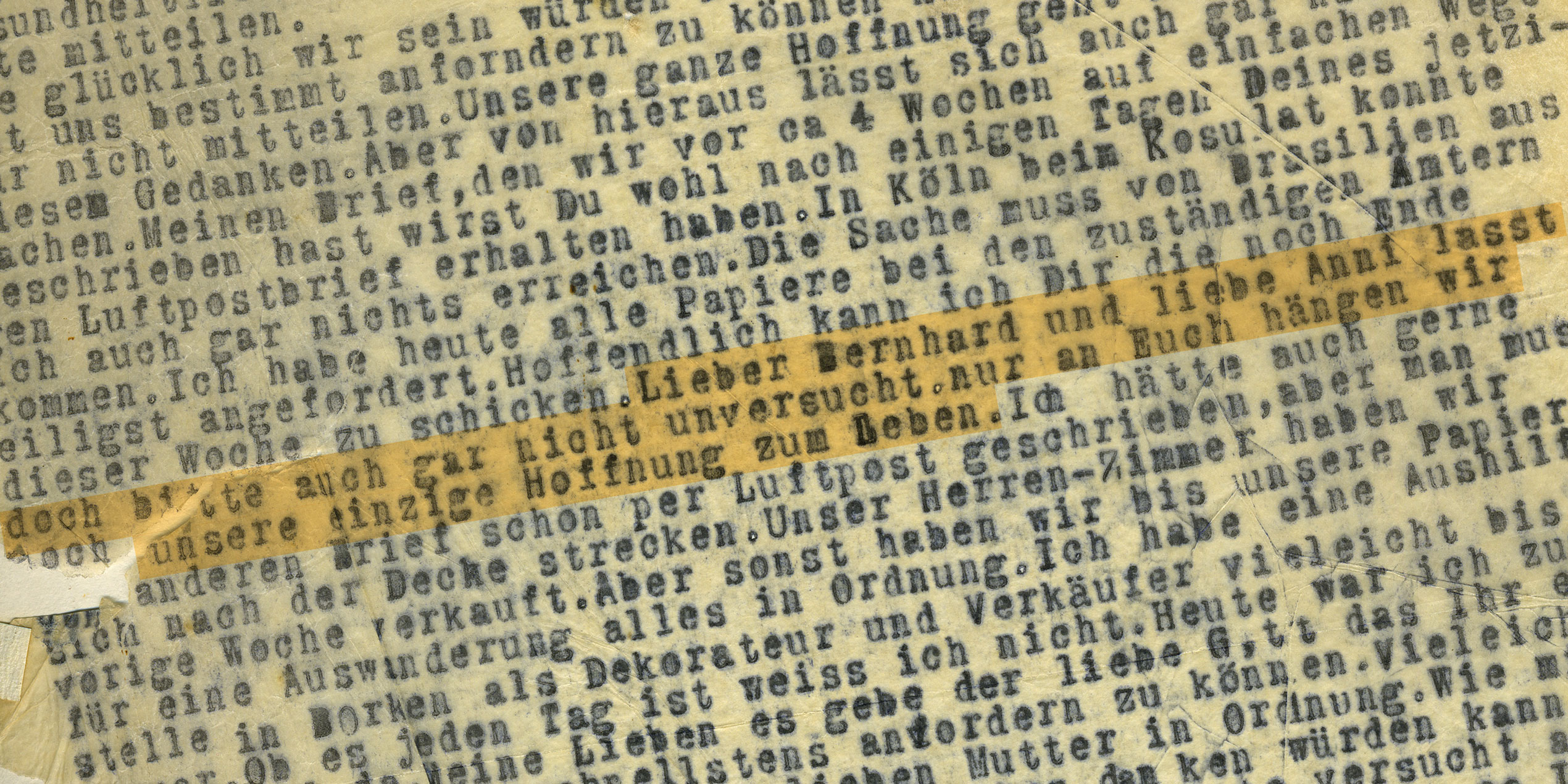

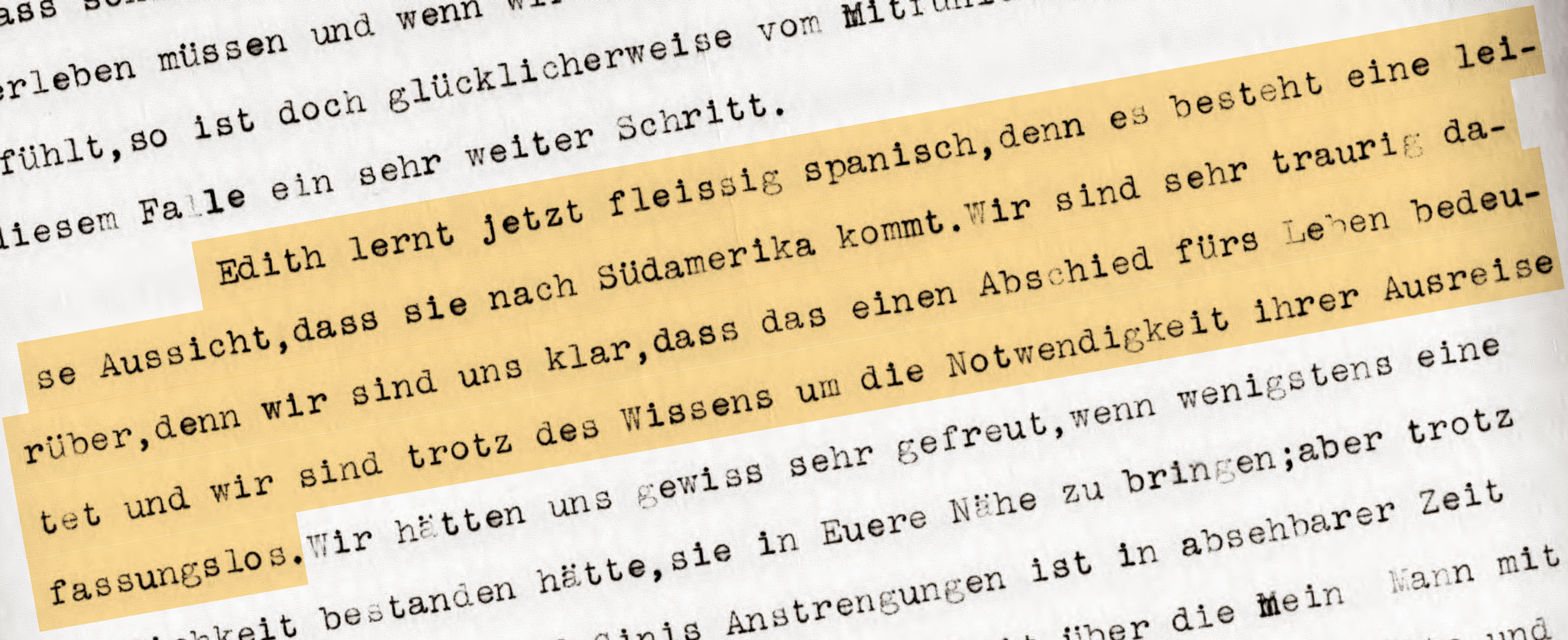

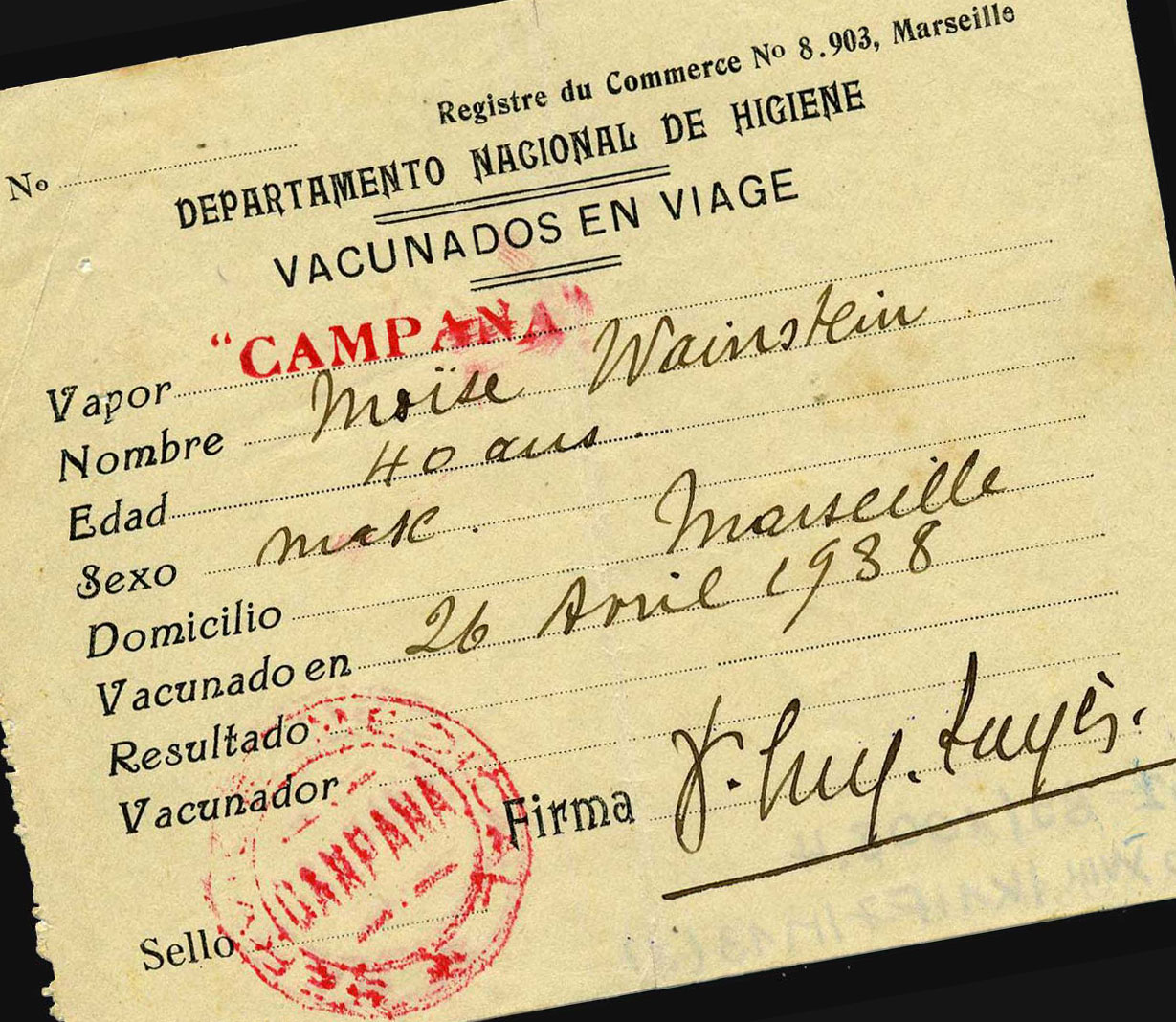

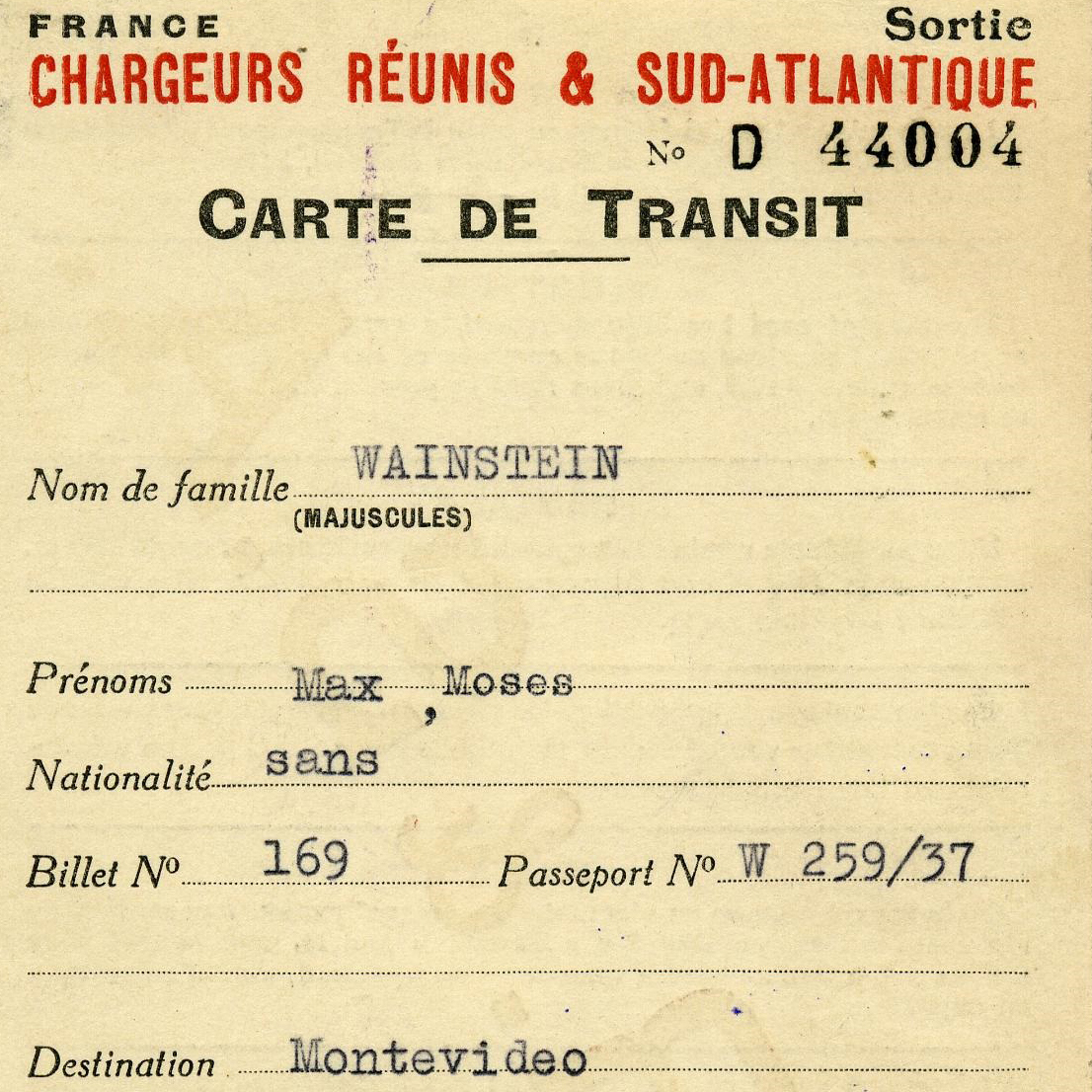

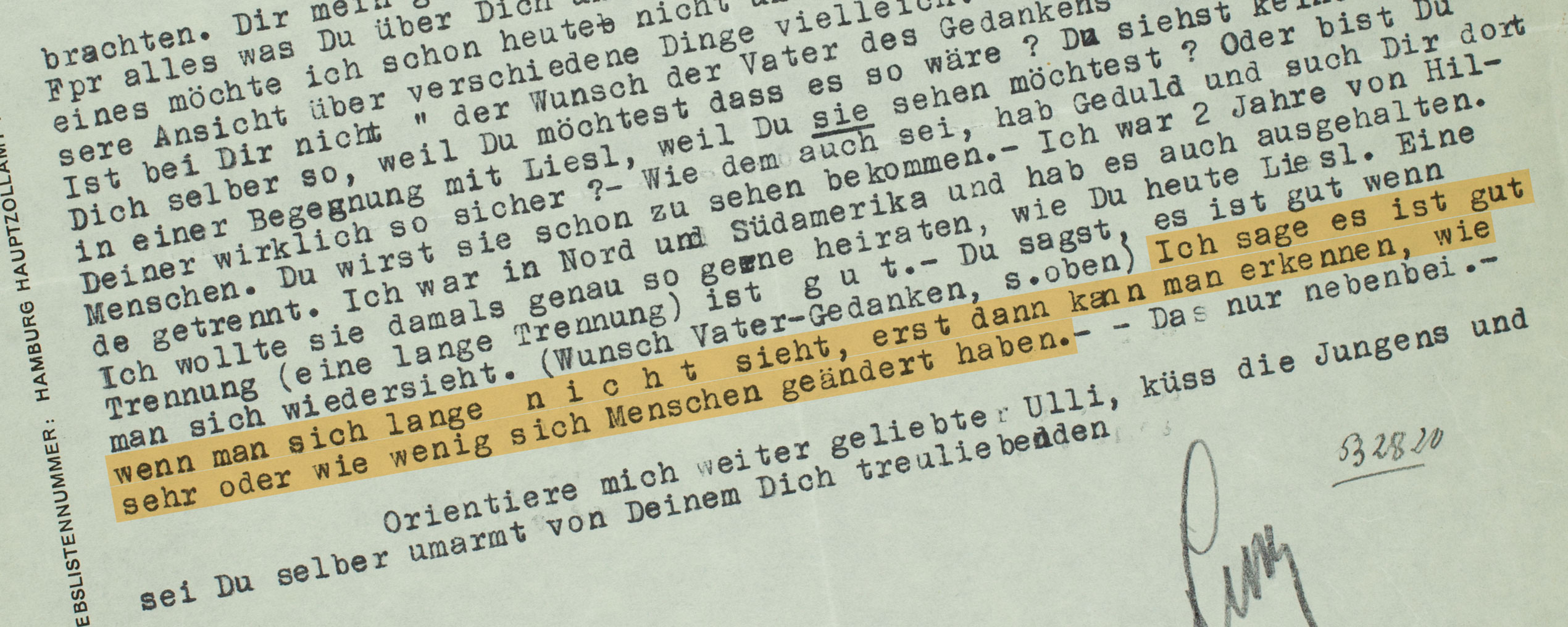

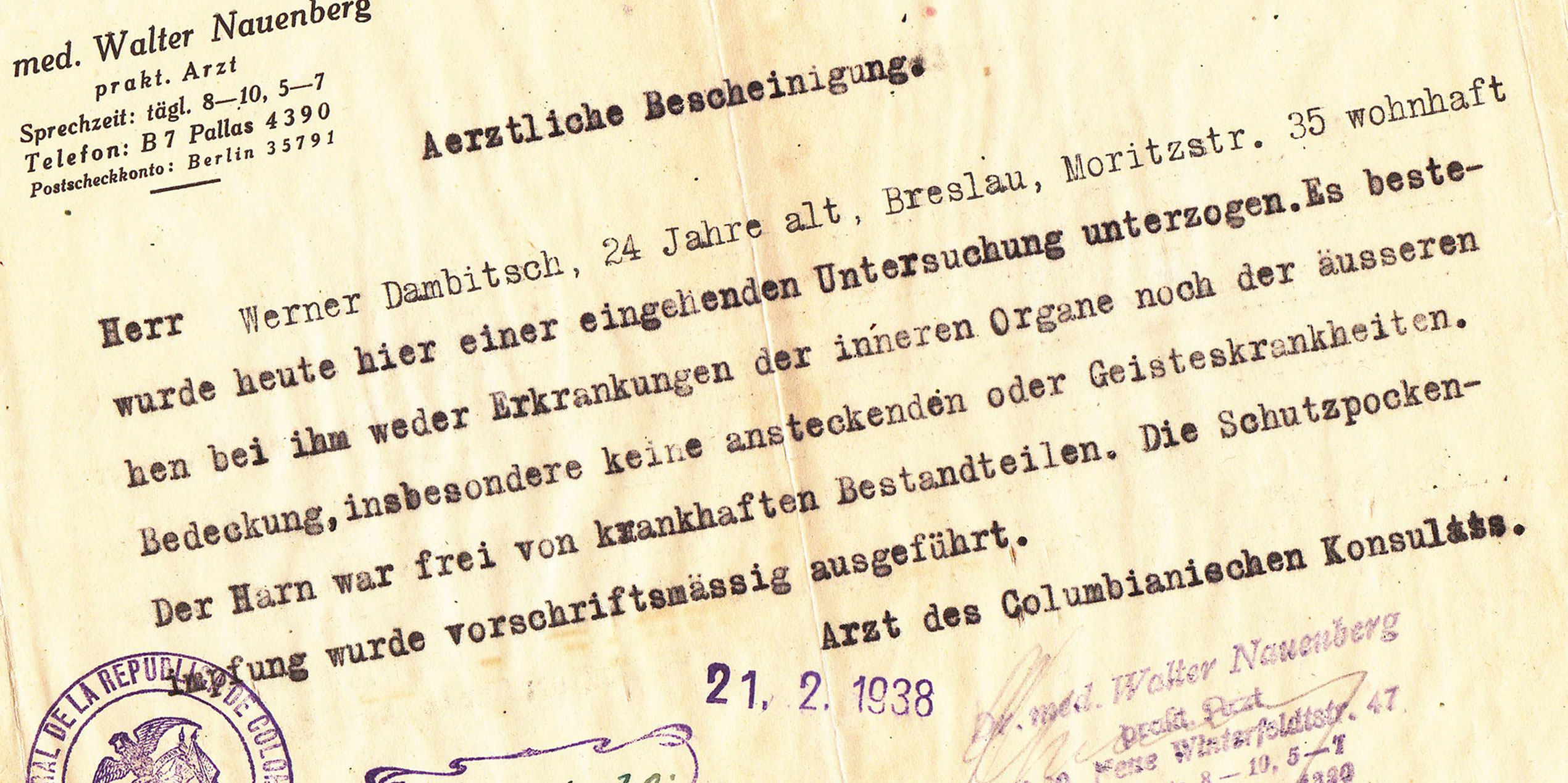

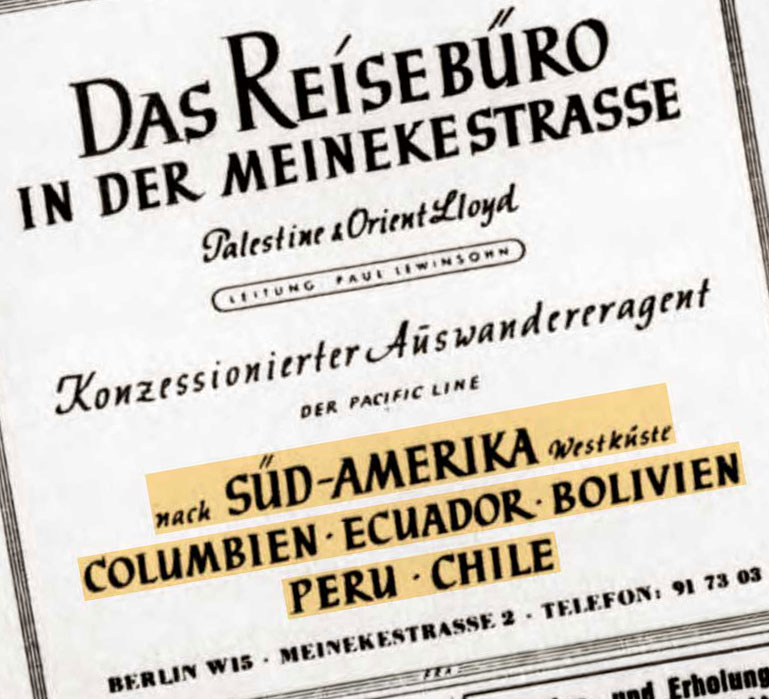

On November 10th, in the course of the pogroms sweeping the entire Reich, Ernst Aldor, an electrical engineer, was arrested in his own home in Vienna for the crime of being a Jew. He was deported to the Dachau concentration camp 366 kilometers west of his home town. On December 9th, he was released. During the period of his incarceration, his wife Renée received an entry permit for Bolivia and a telegram from her cousin, Emil Deutsch, in America, confirming that an affidavit was being prepared. Australia was a third option the couple had considered as a place of refuge. To prepare for emigration, Renée Aldor, a native of Hungary, procured this document from the registry office at police headquarters in Vienna, dated December 20th, listing all her residences in the city since 1920.

SOURCE

Institution:

Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

Collection:

Renee Aldor Collection, AR 10986

Original:

Box 1, folder 3