Alice Urbach's Stolen Cookbook

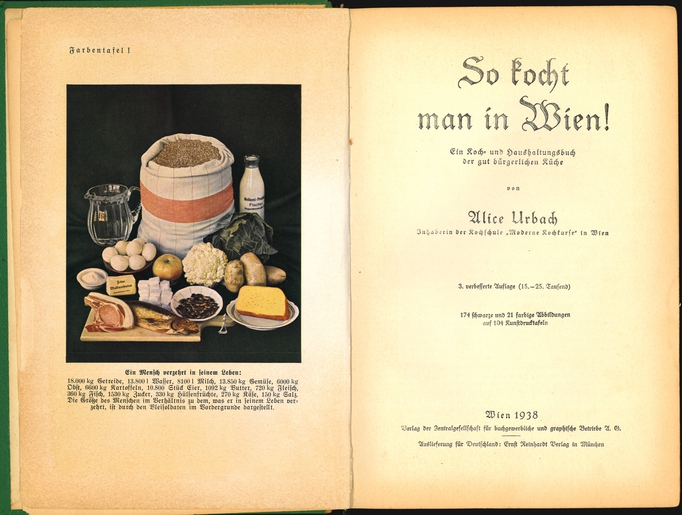

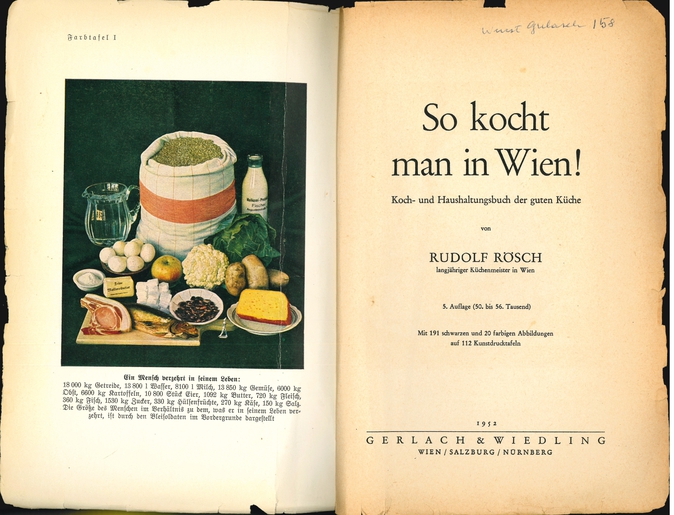

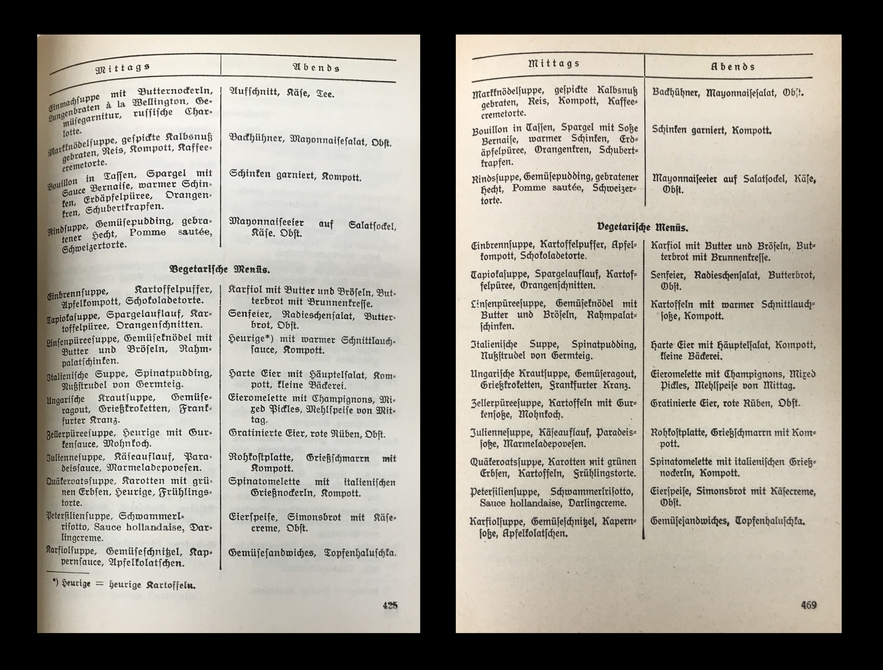

On her first return trip to Austria in 1949, eleven years after her flight to England, Alice Urbach passed a bookshop window. There a title caught her eye, So kocht man in Wien! by Rudolf Rösch, a thick, heavy and exhaustive cookbook of nearly 600 pages. But the book contained her recipes and around a hundred black-and-white photos of her hands. Alice had been years before a single, working mother of two, whose book of traditional Viennese cooking – based on her extensive experience cooking and teaching – had been a bestseller until the annexation of Austria. Unbeknownst to her, the publishing house had continued to sell her cookbook during the Holocaust using another name.

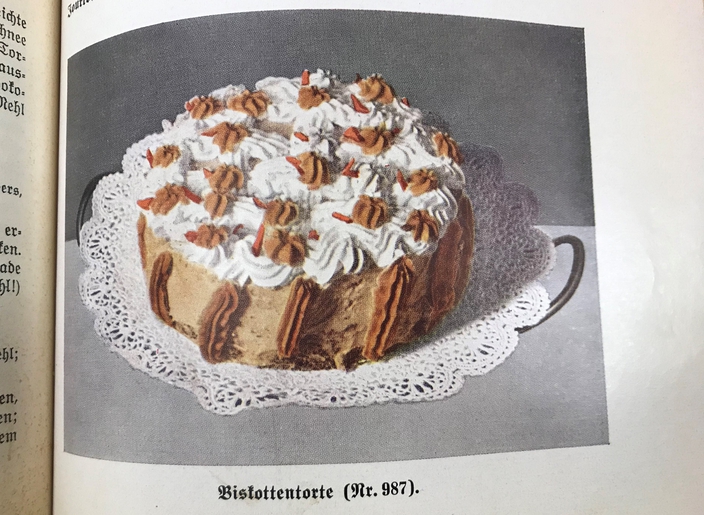

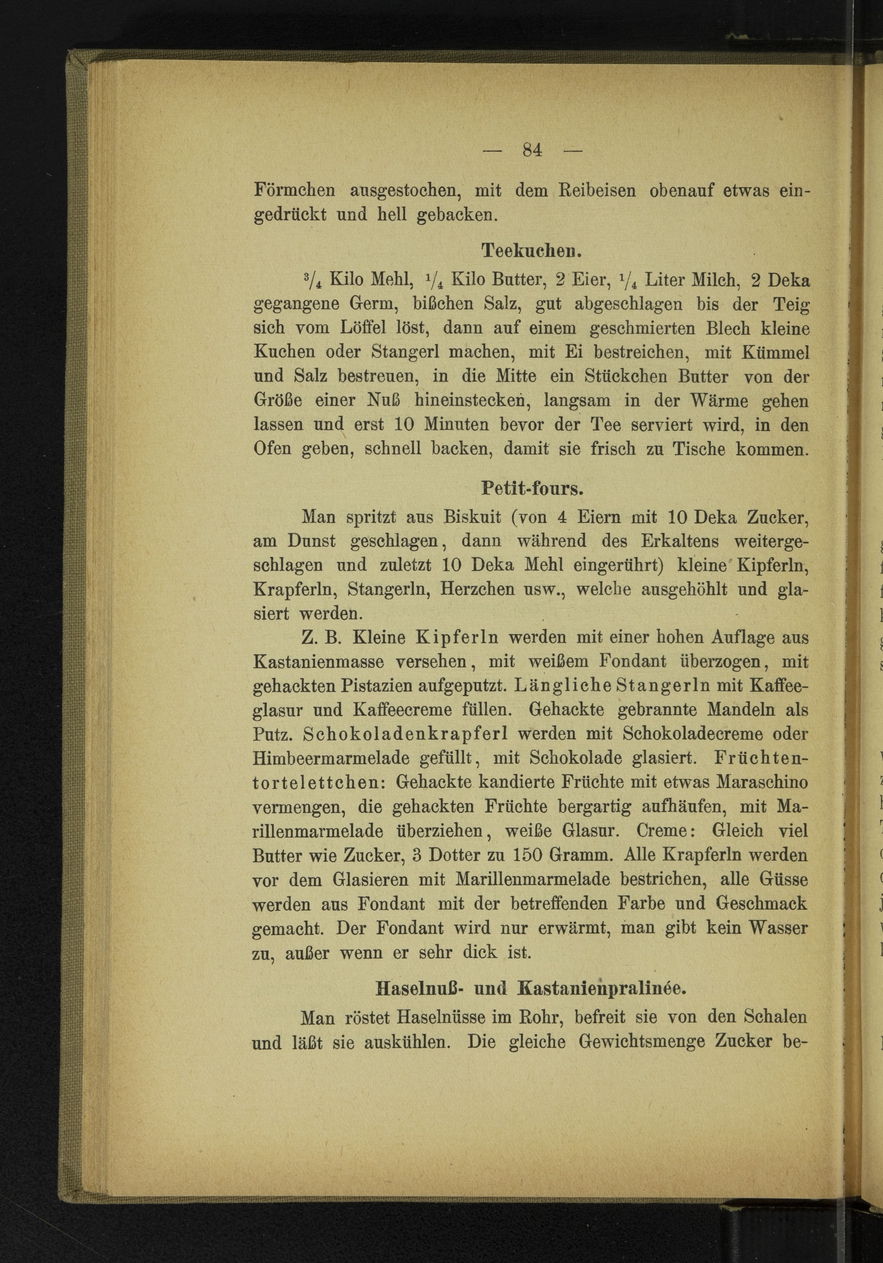

The story of Alice Urbach’s cookbook (documented in her granddaughter Karina Urbach’s biography Das Buch Alice) is one of ingenuity and persistence. Her father, Salomon Meyer, was raised in poverty in Pressburg, becoming a successful businessman. Alice grew up in a wealthy Viennese family, and was educated to become a lady. She had piano lessons and singing lessons but was not taught a profession. As a child she dreamt of becoming a cook. She attended a “very exclusive snobby cooking school,” where she learned to cook from a French pastry chef from one of the best Ringstrasse hotels. “This Cordon Bleu cook from the Ringstrasse taught me things that later would be my lifeboat,” she later wrote. At first, cooking was just her hobby. She would make desserts of self-made bonbons, petit-fours, and other sweets.

Like all young women from well-to-do families, she was expected to marry - not pursue a profession. Under pressure, she married the physician Max Urbach in 1912. The marriage was a poor match and a bad experience. She was forced to leave her home in the beautiful Döblinger Cottage Quarter and move to Ottakring, a poor, crowded neighborhood. Here she saw how hard the life of a working-class woman could be. The birth of her first son Otto in September 1913 brought her great joy, though her marriage continued to be unhappy. Max Urbach spent much of his time out drinking and playing cards. He seemed to have a gambling problem, which damaged the family’s financial stability. The First World War added to the family’s financial stresses.

Alice’s second son was born November 1917. When Alice’s husband died in April 1920, Alice was relieved - by then, he had spent most of her savings and left her with almost nothing. Additionally, her father passed away and left her with relatively little inheritance. With two sons and without a proper professional training, Alice was in a bind to find financial support. It was during this time that her ingenuity and tenacity shined through.

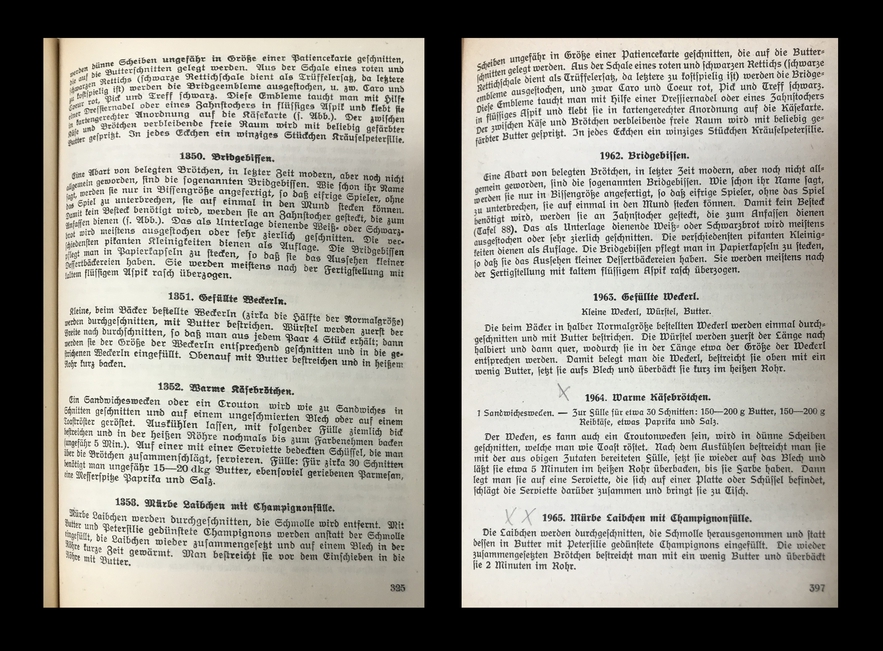

At first, she took in young women boarders, for whom she would bake cookies and birthday cakes. As the financial situation in post-war Austria improved and people had more money to spend, Alice began catering for parties, notably her sister Helene Eissler’s bridge parties. Through these parties, Alice designed her first famous dish. Bridge parties would last a long time, and no one could put their cards down during the game. Thus Alice’s Bridge-Bissen, small bites of food on white or dark bread held together with a toothpick that could be eaten without cutlery and without putting down one’s cards.

Impressed with her food, party guests began asking for cooking lessons. Alice went to an ironware store with a test kitchen and asked if she could use it for classes. Her first session had only one student, and Alice was so nervous she forgot to add the sugar to the recipe. Despite this early mishap, positive word quickly spread and soon her cooking class was crowded. She became so popular she was able to open her own cooking school. It became a must for young girls to attend a class with her. Alice also started a delivery service for prepared ready-to-eat food, probably the first service of its kind in the region.

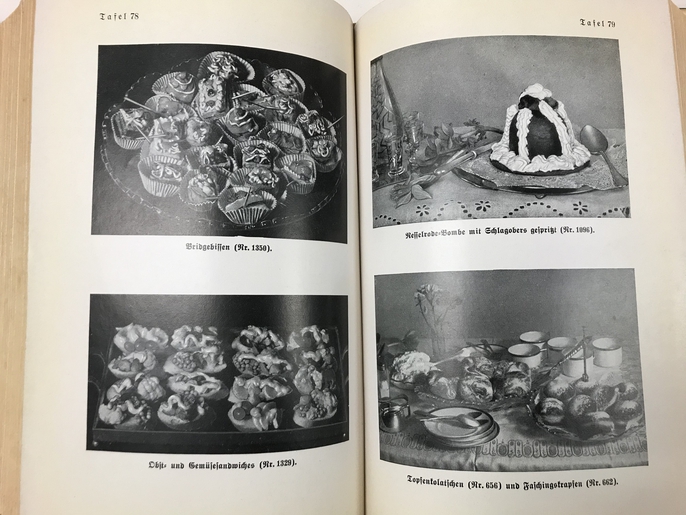

Her sister, Sidonie Rosenberg, was a journalist, and with her help Alice published her first cookbook. Das Kochbuch für Feinschmecker (“The cookbook for gourmets”) was a collection of true Austrian “family recipes” for daily use, festive occasions and cheery Kaffeeklatschs, designed to impress guests. It contained 50 pages of cakes, ice creams, and confections, and a few pages of appetizers like Pastetchen (filled savory pastries).

While Alice’s pursued her newly found career as an author and cooking instructor, her first son, Otto, left home at an early age to travel. Headstrong, Otto chose to study to become an auto mechanic, an unconventional profession for someone from a well-to-do family. Through his travels he made a connection with Dexter Keezer, the president of Reed College, a small university in Portland. Keezer brought him on as a ski instructor and exchange student. Otto would go on to found the college's ski team and help build its ski cabin (built in an Austrian-style). As part of his arrangement to study at Reed College, Alice had to take Reed student boarders in Vienna. Family legend has it that, after his departure, Alice did not know where he was until boarders began showing up in 1935 at her home. Although an inconvenience, it was through connections Otto made at Reed College, including with his classmate Cordelia Dodson, that aided him in staying out of Austria and his brother Karl in leaving Nazi-occupied Austria.

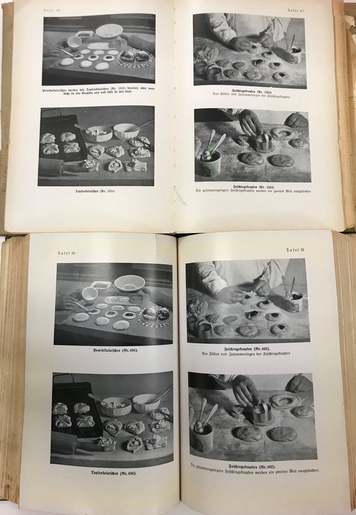

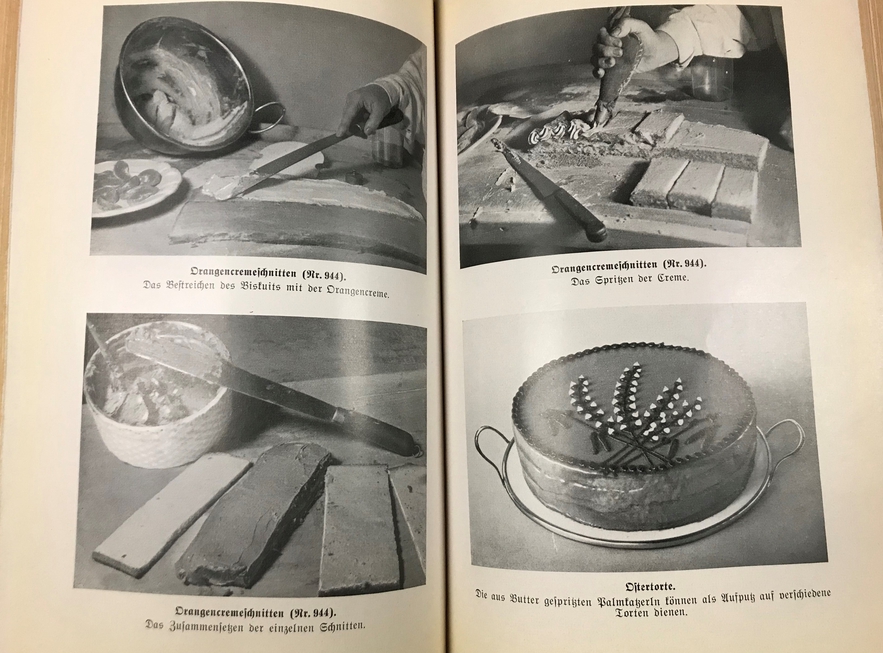

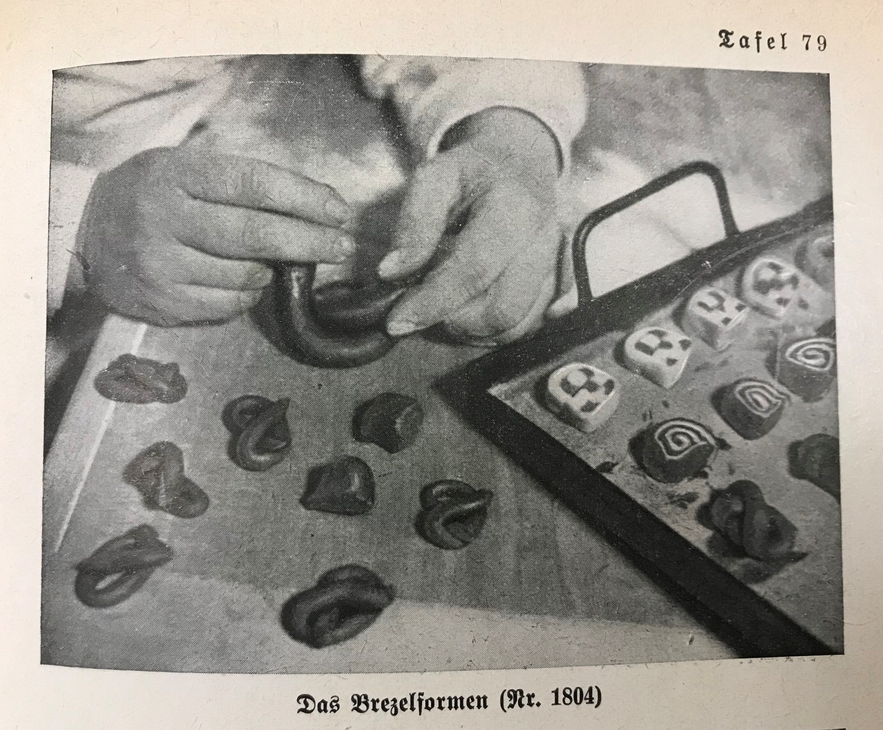

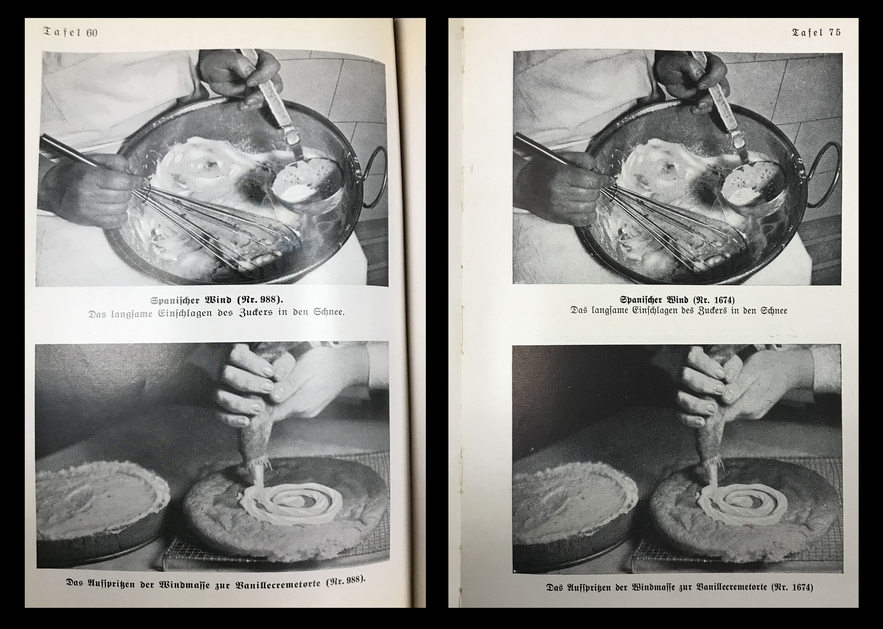

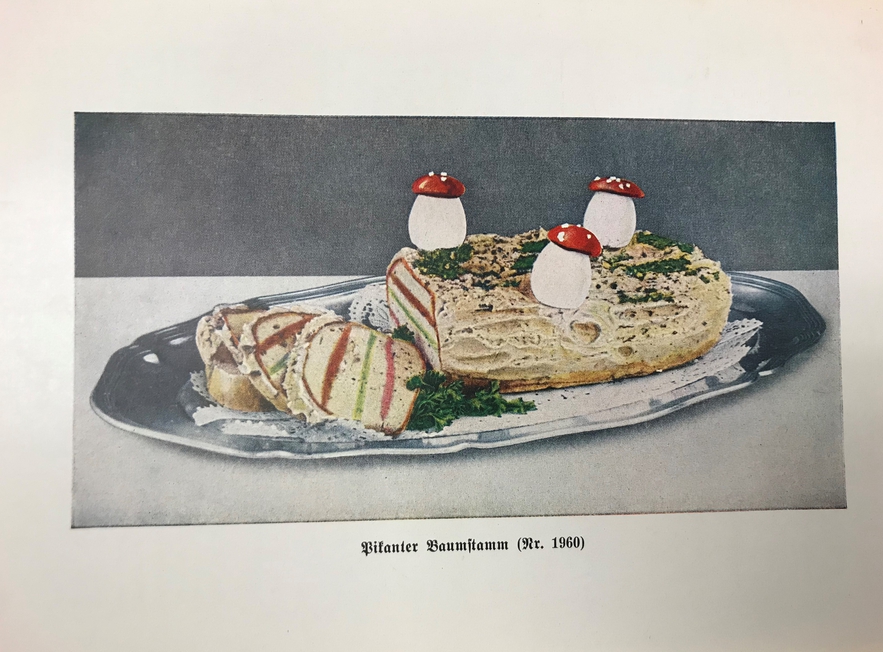

After her first cookbook, Alice continued to collect and develop recipes, which she eventually gave to the publisher Ernst Reinhardt as a manuscript for her second cookbook. So kocht man in Wien!, published in 1936, became a bestseller. By 1938, it was on its third edition, with a print run of 15,000 to 25,000. In the book were numerous black and white photos of Alice’s hands demonstrating cooking skills, but none of her face.

In March 1938, Austria was annexed by Germany. Life became exceedingly difficult for Jewish Viennese. Karl Urbach lost his position at the University of Vienna and could not even retrieve his books. While Alice Urbach found a position in England and was able to leave Vienna, Karl had to wait for an affidavit from his brother in the U.S. He continued to work small jobs, like delivering coffee, while waiting many hours in lines for immigration papers. On the day after Kristallnacht, Karl went to get a necessary paper for his immigration and, like many other Jewish men in Vienna, was picked up by Gestapo. They were loaded into cattle trucks and taken to Dachau. In 1939, Karl was released - it is unclear why that happened. He immediately left Austria after this imprisonment, arriving in the United States in 1939.

In England, Alice Urbach continued to work as a cook until she and her friend Paula Sieber opened a hostel in Windermere for Jewish refugee girls from the Kinderstransport. In interviews, former residents of the Windermere hostel spoke of that time. Speaking with the Austrian Heritage Collection , Alisa Tennenbaum (born Liselotte Liesl Scherzer) said, "She had a cooking school in Vienna. So we were never without food. Even during the war ... from carrots we got a birthday cake." Ilse Camis remembered, "The matron happened to be my mother's teacher in Vienna in her cooking school ... We had to do our own cleaning [in the hostel]. The matron taught us in the kitchen." Another resident, Anita Heufeld Fellner, described Alice and Paula as insufferably strict, especially about cleaning and housework. Alice, with her experience as a cook, and Paula, who had run a movie theater in Vienna, were both very capable managers, but had little experience running a home for girls. In a biography Anita Fellner commented that,"[t]he two women [Alice and Paula] who ran the home came from Vienna and didn't understand anything about dealing with children ... No one knew anything about psychology yet."

Alice’s cookbook continued to be published, but due to Nazi laws prohibiting the publication of “Jewish” books, it could not be published under her name. By this time, the original publisher of So Kocht man in Wien! had passed away and the company had been taken over by his nephew Hermann Jungck. In the Nazi period, it was not uncommon for a publisher to change a work’s author, if the original author was Jewish, or to plagiarize a text written by a Jewish author. Two editions of So kocht man in Wien! were published in 1939, but this time under the name Rudolf Rösch. On the title page, Rösch is described as a “langjähriger Küchenmeister” (a longtime master cook). There is no concrete evidence that this person ever existed.

Alice and her two sons managed to survive World War II. After arriving in the United States, Karl worked odd jobs as a roofer, ski instructor, and fire fighter, graduating from Reed College in 1942. He completed his Ph.D. from Northwestern University in 1950 and worked in the US Public Health Service. Otto Urbach joined the American military and was involved with counter intelligence. Alice continued to run her hostel for Kindertransport youth until, after the war, she immigrated to the United States, where she worked as a professional cook for private parties, was a nutritional specialist, and, as a retiree, a teacher of Viennese cooking. Her sisters, Sidonie and Helene, both perished in the Holocaust.

Though her cookbook no longer had her name, she was often stopped on the street in San Francisco and New York by people who remembered her and her cooking school. Alice’s book continued to be published - and profited from - through the 1960s with the name Rudolf Rösch. Alice never received any compensation for her stolen book.

Additional sources:

AHC interview with Lilly Mendelsohn-Urbach about her husband Karl Urbach. Leo Baeck Institute, AHC 756. San Francisco, 2008.

AHC questionnaire with Karl F. Urbach, completed in 1998. Leo Baeck Institute, Austrian Heritage Collection, Questionnaires, AR 10378.