Hélènemama's Austro-Hungarian Gourmet

A Jewish Refugee's Love for Viennese Cuisine

The Kochbuch der Hélènemama (“Cookbook of Mother Helena”) was first published in Arad, Romania in 1920, followed by a second edition in 1924. Hélènemama was published in the German language in Romania. Although it is not written for a kosher kitchen, this book came to the Leo Baeck Institute as part of a collection of cookbooks and manuscript recipe books donated by Hedi Levenback, a Viennese Jewish refugee.

Hélènemama was probably published for the German-speaking minority in Romania, which included many Jews. Arad itself had a German-speaking population that was substantial until the end of the Second World War (even today, a small number of ethnic Germans still live in Arad). The cookbook does not appear to have any ethnic recipes that are Romanian or from countries of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. The non-German or non-Austro-Hungarian recipes are fanciful items adopted for the German kitchen, such as “French Lamb,” “Brazilian Cake” or “Gnocchi Palmyra”. In countries of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, food was often seen as a sign of identity. For example, Hungarian Goulash became a symbol of Hungarian nationalism to the Hungarian separatists working towards a Hungarian nation independent of Austria.

One can guess that ethnic Romanian cookbooks contained very different recipes than this German-language cookbook does. Arad was a very Hungarian city prior to WWI (it borders Hungary today and geographically is considered part of the Great Hungarian plain-Alföld). The Romanian population in the area lived in the countryside, while the Hungarian and German population lived in Arad itself, so it would make sense in any case that Romanian recipes weren’t included. Romanian dishes might have been considered peasant food recipes, not included in cookbooks for the cosmopolitan city dweller. On the other hand, the book does include some Hungarian items.

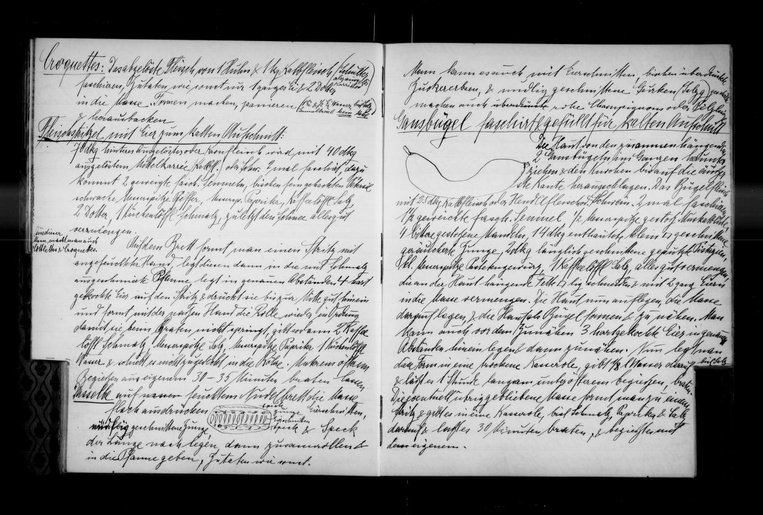

This cookbook, like many others in the Leo Baeck Institute, assume the readers, housewives and cooks, already know the basics of cooking. Directions can be sparse on measurements or cooking time. Some recipes begin: “Make loose yeast dough” or “add an amount of lemon juice” or other sentences that, for the modern chef and baker, could make or break a recipe. The author also urges the cook to use a sense of poetry (“poesie”) with the recipes.

Hedi Levenback, the owner of the copy of the Kochbuch der Hélènemama at the Leo Baeck Institute, was born in Vienna, although her paternal grandparents had been born in Budapest. She escaped Austria in 1939 via a Kindertransport to England at the age of 14. Her own mother had died of natural causes when she was only six, and she was raised by an aunt. Her aunt managed to flee Austria as well, immigrating to Shanghai and, after the war, joining her niece in New York. After arriving in the United States, Hedi Levenback became a senior consultant in early childhood education with the New York City Department of Education. She was considered a pioneer in her field. It appears this cookbook belonged to her aunt, carried with her from Vienna to China and to her new life in the United States. She seems to have been truly devoted to the domestic arts. The collection contains a large body of published cookbooks, but also handwritten recipes; as well as needlepoint and sewing patterns which she also brought with her into exile–reminders of a lost domestic home.

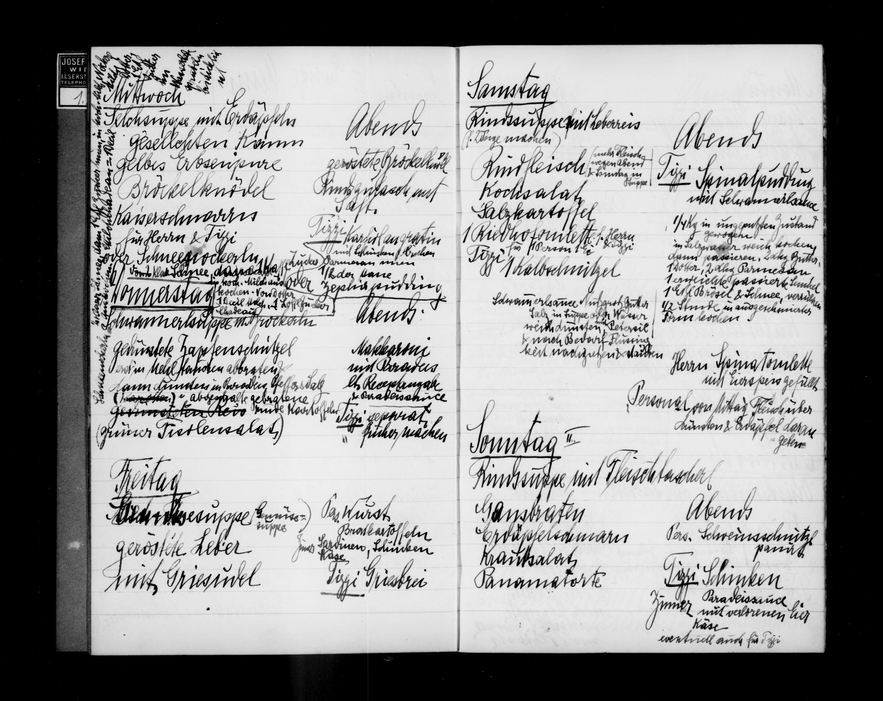

The meals described in the manuscript notebooks of the Hedi Levenback Collection are as luxurious as Hélènemama's Austro-Hungarian recipes. One notebook in the Levenback collection shows how elaborate meals in Vienna were compared to meals today. These meals included an appetizer (usually soup), followed by a main course and one or two side dishes, and a dessert. Here is one menu for a Sunday meal: beef broth soup, followed by roast duck with potatoes, and a cabbage salad. Dessert was a "Panamatorte," a layered chocolate almond cake.

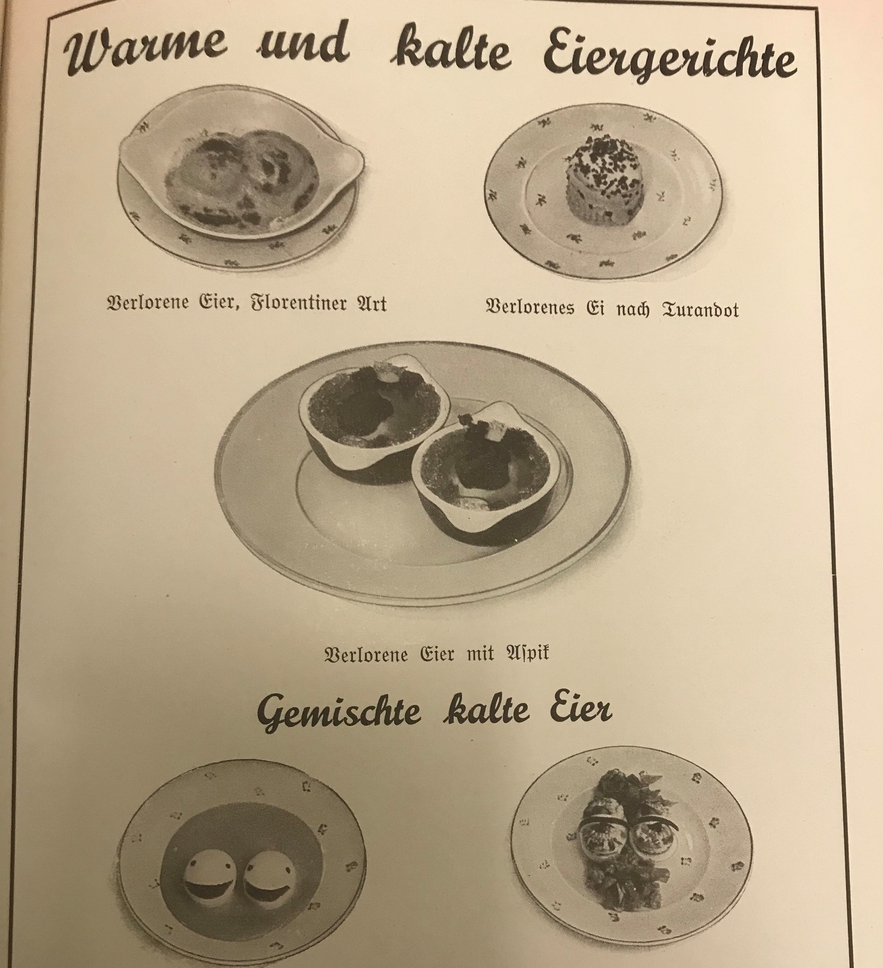

Interestingly, written next to the main meals on the sides of the pages are simpler meals for "Tizzi" (possibly a child), who was served dishes such as "Paradeissauce mit verlorenen Eier" ("paradise sauce with lost eggs” -- poached eggs in tomato sauce) and "Griesbrei" ("semolina pudding"). There are also separate simple menus labeled "personal" for dishes such as schnitzel and sausage with potatoes. (These "personal" dishes may have been for a house cook.)

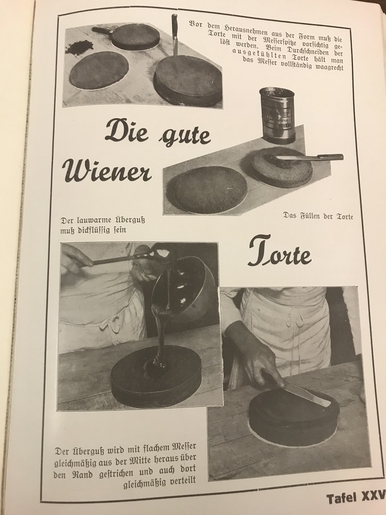

In the Hedi Levenback Collection are also two notebooks formerly owned by Juliane Steiner and "diktiert von meiner lieben Mutter" ("dictated by my darling mother"). Juliane Steiner's notebooks contain pages of mouth-watering savory Austro-Hungarian recipes like "Eierschwammerlgulasch" (a goulash made of chanterelles), "Paprikahuhn" (paprika chicken), and "Serviettenknödel (a type of bread dumpling served in a napkin). The sweet recipes are even more delicious: "Dobotorte" (a buttercream and caramel layered Hungarian sponge cake), "Indianerkrampfen" (a cream filled doughnut), "Palatschinke" (a filled pancake), "Milchrahmstrudel" (milk-cream strudel), and at least five variations of Linzertorte.

The effort with which hundreds of handwritten recipes and a dozen of cookbooks were held on to and carried with Hedi Levenback's family as they fled Austria - despite separation and loss - reveals a strong relationship between family, memory, and food. The recipes and cookbooks were passed on to generations, in part preserving a legacy of the kitchen as Levenback began a new life in America.

Bibliography:

Roden, Claudia. The Book of Jewish Food : An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York with more than 800 Ashkenazi and Sephardi Recipes. New York : Knopf, 1997