From Prague to Princeton: Tracing the Story of the Kulbach Family

- Author

- Sarah Glover

- Date

- Fri, Nov 1, 2019

Devotion, heartache, intrigue, New Age spiritualism, the von Trapp family, a love triangle, and even Matthew Broderick! The Frankl-Kulbach family collection has it all. Once members of the German-Jewish intellectual elite, the Kulbachs survived wartime Germany, endured the trauma of immigration, and established new lives in the United States. Piecing together photos, letters, and other archival materials, Center for Jewish History archivist Sarah Glover brought their story “Out of the Box” at the first in a new series of public programs that give audiences a chance to immerse themselves in the story of a single family the way that archivists do when they process collections.

One of the best parts of my work as an Archivist at the Center for Jewish History is the incredible opportunity to process collections held by the Leo Baeck Institute. LBI’s distinctive holdings of extremely personal family collections provide a unique insight into the lives of Jews in German-speaking countries before and during World War II. Of all the captivating collections I’ve worked on, none has grabbed me like LBI’s Frankl-Kulbach Family Collection (AR 25568). On June 12, I presented stories from the collection as part of the Center’s new “Out of the Box” series.

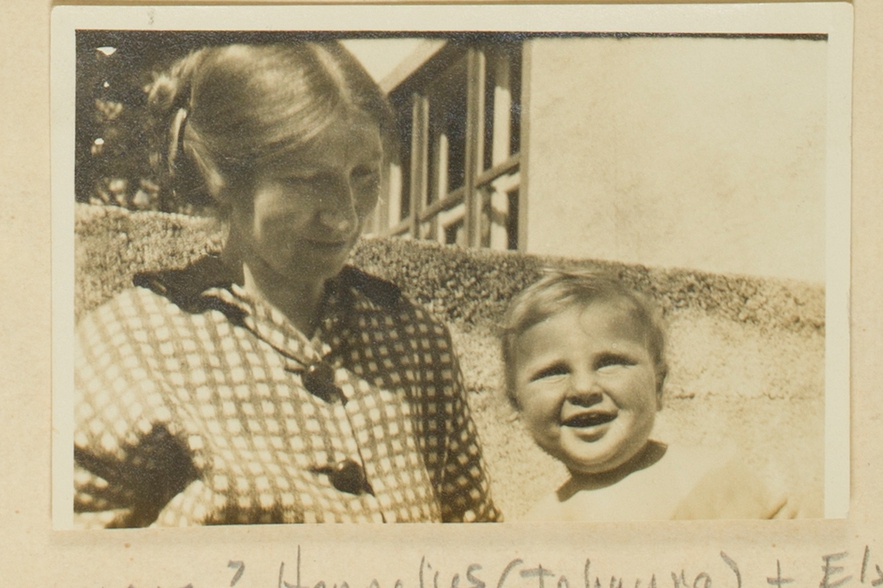

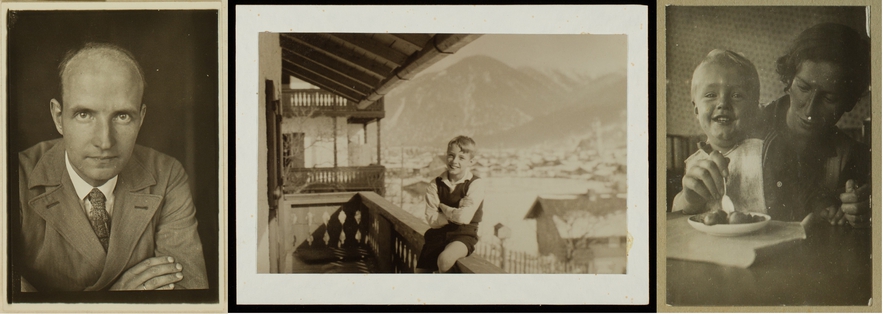

The story begins in Prague, where Paul Frankl (noted art historian and descendant of a prominent Sephardic rabbinic family) was born in 1878. Paul married Elsa Herzberg in London on June 28, 1905. Why London? Their first son Peter was born January 2, 1906—just six months later. Elsa was an artist and, let’s say, a character. As her granddaughter Lisle Kulbach later wrote: “As the professor’s wife, Elsa was not one to follow the rules. She never wore the gloves you were supposed to wear, nor the hat, and when visitors came to the door on Sunday for tea, Elsa would pretend she was not home, rather than endure a formal and boring setting.” Furthermore, “Elsa was not someone to follow the crowd. Her interests were art and music […]. She would, for instance, sing at the table. This was not good manners. Paul, rather than say outright to his wife ‘Stop singing,’ would tell one of the children ‘There is no singing at the table.’”

Elsa’s father was a non-believing Jew, and her mother was a Huguenot. Paul had converted to Catholicism in order to attend university in Germany, and Elsa considered herself, through her mother, to be Protestant. Their five children were raised as Protestants. As Lisle wrote: “My mother Johanna [Paul and Elsa’s daughter] always thought of herself as Protestant, was confirmed as a Protestant, and according to Jewish law […] was not Jewish, but the Nazis counted my mother as Jewish. The Nazis thought of everyone in my family as Jewish, although a Seder had not been celebrated in several generations […].”

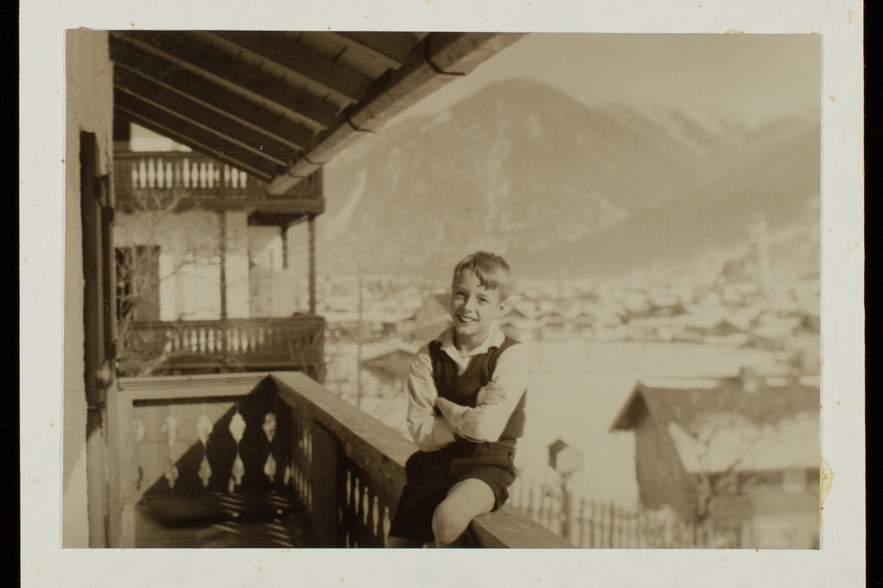

For Johanna, who survived the war in Berlin, the ostracism she endured at the hands of former friends on account of her Jewishness was especially painful. Johanna married Richard Kulbach on May 13, 1933, just two months after Richard’s first wife died from tuberculosis. Richard had read Mein Kampf and feared that if he did not marry Johanna immediately, he would not be able to. Due to his marriage to Johanna and his “anti-Fascist attitudes,” Richard lost ownership of his bookstore. Worse yet, he lost custody of Bernhard, his son with his first wife.

Richard’s German Lutheran family also considered Johanna to be Jewish. In 1937, Bernhard went to visit his aunt Ella (Richard’s sister) and Ella’s husband Jo, a member of the Nazi Party. They refused to give him back on the grounds that Johanna’s Jewishness made her “unfit” to raise a child. In 1938, Richard went to court to get his son back, but the court ruled against him as “the government found [his] politics to be untrustworthy and unreliable.” Richard would not see his son again until the war’s end. He would also discover that, in the interim, Bernhard had been raised to believe that Ella and Jo were his parents.

During the war, Johanna was compelled to spend her days peeling potatoes under the supervision of the Gestapo. Richard was eventually put into forced labor, given the demeaning task of “cleaning” printing presses with soap and water—presses that, in fact, could not be cleaned with soap and water. In November 1943, Richard and Johanna’s apartment was destroyed by a chemical bomb. All through this time, Richard kept up correspondence with his good friend Bertha (Fränzl) Krimke. While he did mention the hardships that he and Johanna suffered, what is truly incredible about these letters is that the couple’s hardships are not the focus of the correspondence. More prominent are musings on his readings of Goethe and Spinoza, classical music on the radio, and plays attended. Even after the loss of their apartment and nearly all their possessions, Richard focused on the books he managed to save. On October 12, 1943, he wrote, “We rescued the collected works of Goethe, Gottfr. Keller, Eichendorff, Plato, Th. M., an old Bible, Schweitzer, J.S. Bach, and the essentials of Spinoza. I believe, if we can still rescue that from all future threats, we would have enough for the rest of our life.”

In January 1943 he wrote, in a moment of haunting foreshadowing, “A few days ago Johanna said to me that perhaps we would determine later that these ten years now behind us had been the happiest and most contented of our lives.” Sadly, Richard and Johanna would not have many more years together. On January 20, 1949, while working in the Dahlem Museum, Richard stepped into an empty elevator shaft, falling one story and breaking his neck. He died that night.

Johanna immigrated to the United States with her daughter Lisle (born April 4, 1948), where she was reunited with her parents and sisters. She was a music teacher, teaching recorder to children at schools throughout New York City. One such student was a young Matthew Broderick, about whom she wrote, “Matthew Broderick at least half of the time comes without recorder and books. He cannot find it, is his remark. Sometimes he plays well, sometimes not. He reads the notes but seems not to read otherwise, since he never finds the song titles in the book. His concentration span improved during the year, it was the best sometime after Christmas, now it is less again.”

Johanna also taught at various summer music camps, most notably the Trapp family music camp in Stowe, Vermont. Photographs show Johanna and various members of the Trapp family, including Maria, in the mountains of Vermont, relaxing, playing recorder, and yodeling. “Mother” Maria Trapp sent young Lisle postcards from her travels and wrote to Johanna asking for help finding yoga classes in New York City. A lifelong music lover, musician, and music teacher, Johanna died on July 21, 2010.

At the end of the “Out of the Box” program, an attendee asked me if members of the Frankl-Kulbach family—baptized and buried in a Quaker cemetery in Princeton—had in any way returned to their Jewish roots. Too hastily, I almost said no. But then I remembered Lisle Kulbach, daughter of Johanna and granddaughter of Paul and Elsa, who lives in Boston and is a founding member of the Sephardic musical ensemble Voice of the Turtle. She is preserving a musical tradition that links her to the Sephardic forebears of the rabbinic family that produced her grandfather Paul. The entire family’s story is also now preserved among the thousands of German-Jewish families’ stories in the LBI archives.

From LBI News No. 108