Sparkling Water and Sparkling Conversation on the Upper East Side

- Author

- Christopher Rochow

- Date

- Fri, Nov 1, 2019

It became a ritual. Whenever I entered Franz Leichter’s apartment on New York’s Upper East Side, he offered me a glass of sparkling water, because he knows I like it. He is just as sharp a conversation partner as he is an attentive host. Wide-ranging political analysis flows freely, ranging over the collapse of democracy in his native Austria to the current political landscape.

It’s no wonder that Leichter likes to talk politics. He was a member of the New York State Senate from 1975 until 1998 and a member of the New York State Assembly before that. Representing various districts that included Washington Heights, where he had found refuge with his brother, Henry, and father, Otto, in 1940, Leichter was a progressive stalwart. In the Assembly, he drafted the Cook-Leichter bill, which expanded abortion rights when it became law in 1970 and later influenced the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in its Roe v. Wade decision. In the tradition of his father, a prominent Austrian socialist writer and activist, Leichter saw himself as an advocate of working people and left a legacy of tenant and consumer protections in New York State before joining the Federal Housing Finance Board during the Clinton Administration.

With all that, Leichter didn’t have much time left to keep his German sharp. When the Wiesenthal Institute in Vienna re-issued his father Otto’s book on the collapse of democracy in Austria last year, they did so only in German. Franz wanted to read his father’s book, so he called the Leo Baeck Institute hoping they could find someone to help him with the German part. I’m very glad that I became that person.

Between the summers of 2018 and 2019, I worked as a volunteer for the Austrian Heritage Collection (AHC). Since 1996, young Austrian volunteers like myself have worked at the LBI conducting oral history interviews with people who emigrated from Austria to North America due to Nazi persecution. In fact, Franz Leichter gave an interview to the AHC in 2009, and it is one of over 700 such interviews available in audio format in the LBI catalog.

The book we read together was an education for me. Otto Leichter finished Ein Staat Stirbt: Österreich 1934–1938 (Death of a State: Austria 1934–1938) in his Paris exile in 1939 and published it under the pseudonym Georg Wieser. Paris wasn’t Otto Leichter’s first exile. After the February Uprising in 1934—a series of street battles between Socialists and Fascists—the Social-Democratic Party was banned, and Otto fled to Switzerland. He returned to Vienna under cover only to flee again after the Anschluss. During this whole time, Otto was deeply involved in underground work of the Austrian workers’ movement, which he describes among many other things in his book.

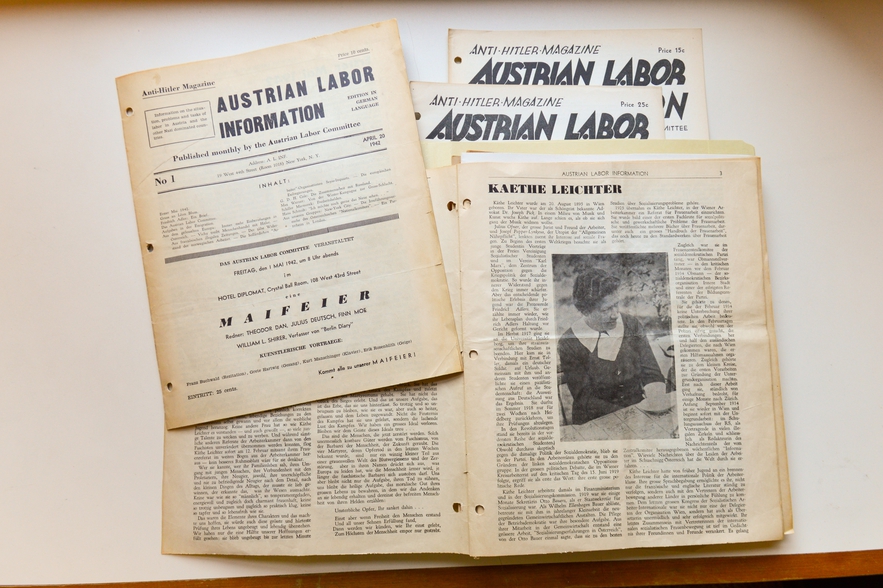

Otto’s wife and Franz’s mother, Käthe, a social scientist who had studied with Max Weber, was also active in the Socialist underground. The family was torn apart when Käthe was arrested by the Gestapo in May 1938. Franz and his brother Heinz (Henry) were able to escape Europe along with their father, but Käthe was murdered in the Bernburg Euthanasia Center in 1942. Otto Leichter rejoined the labor movement in Austria in 1947, but he returned to New York just a year later after his hope for a leftward shift in the Social-Democratic Party ended in disappointment.

I grew up in Germany, so Austrian history, especially the four years of Austro-fascism before the Anschluss, wasn’t something I was taught in school. As an antifascist and a student of political science living in Austria (not to mention my work on the AHC) I was glad to learn more about this period, but that’s not all I learned.

In weekly meetings, Franz and I sat side-by-side on his comfortable couch, working our way through his father’s book, word-by-word, and page-by-page. The long, multi-clause sentences filled with double negatives made for slow going. But we managed just fine, and I could tell that Franz’s German improved, as did my ability to translate 1930s political terminology.

As we read, I found myself as impressed with Franz’s political insights as I was with his father’s. Observing the daily developments of politics—whether in 1930s Austria or today’s New York—both have an uncanny ability to quickly discern the competing interests, ideologies, power structures foreign and domestic, and economic factors that drive them.

One thing that wasn’t so easy was finding reading dates. Most people in New York seem very busy, but Franz is easily the busiest person in his late 80s that I ever met. Franz knows how to make the most of his precious time, which he splits among trips within the US and abroad, visits of friends and family, and excursions to the theater and museums. I was grateful that he was able to work me into his schedule, and for everything I learned from him.

From LBI News No. 108