New Research Tool: German Refugee Rabbis in the United States, 1933–1990

- Date

- Wed, Apr 24, 2019

A new online database tracks the careers and biographies of Rabbis who fled Germany for the United States, and LBI’s rich archival collections figure prominently in the linked sources.

The modern German rabbinate emerged in the German lands early in the 19th century as part of the process of Jewish emancipation. This modern rabbinate, university-trained and immersed in secular knowledge, played a key role in leading German Jewry on the path toward social integration. They also initiated a new self-examination within Judaism through the academic study of Jewish history and tradition, known as the “Wissenschaft des Judentums” or “science of Judaism.”

Since the modern rabbinate was symbolic for Jewish social integration and became the backbone of Jewish communities during Nazism, the rabbinate was particularly confronted by harassment and persecution after 1933. While rabbinical scholars and students sought to leave Germany early on to continue their studies and professional lives, the communal rabbinate faced its largest crisis during the Kristallnacht on November 9, 1938, when synagogues were destroyed and many rabbis were arrested. To gain their own release, many were forced to commit to emigrating from Germany within four weeks.

Thanks to a cooperative rescue effort of the American Jewish seminaries (Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, the Jewish Institute of Religion in New York, the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, Yeshiva University in New York, and Dropsie College in Philadelphia), all institutions with long-standing intellectual and personal relationship with their German counterparts, the United States became the first choice as place of refuge for the German rabbinate. These American seminaries joined with the National Coordinating Committee for Aid to Refugees and Emigrants Coming from Germany (NCC), and the National Refugee Service to establish an Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars, a National Committee on Refugee Jewish Ministers, and a close connection with the International Student Service in order to help their colleagues in Germany.

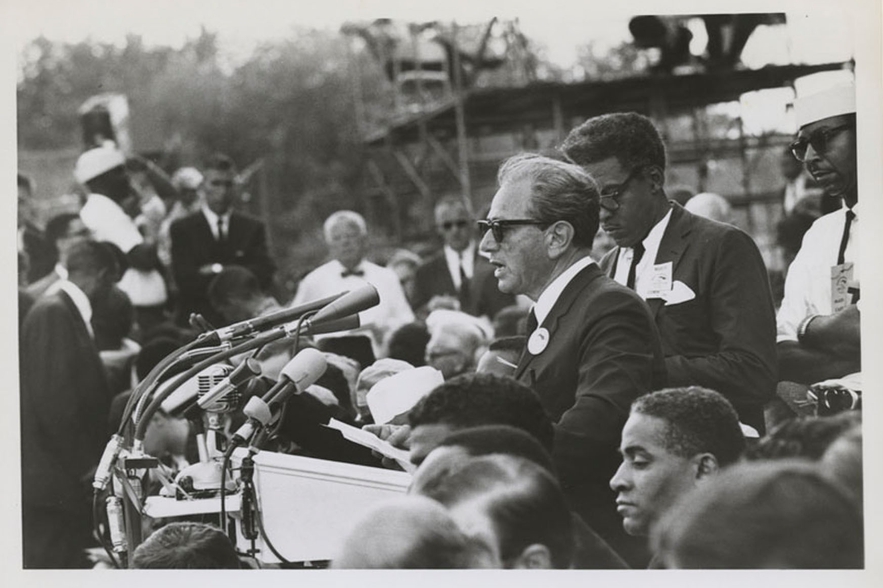

Their work benefited from the existence of non-quota immigration visas available to clergy, students, and visiting scholars. This regulation allowed the American Jews to mediate opportunities for short-term rabbinical positions of two years at a minimum salary in exchange for immigration visas for qualified refugees from Germany, or to transfer scholars and students to either one of the rabbinical seminaries in the US. Based on this cooperation, roughly 250 refugee rabbis, rabbinical students, and scholars found their way to the United States after 1933, and a large number of them continued their careers as rabbis quite successfully in the United States. Among them were Joachim Prinz, Max Nussbaum, Alfred Jospe, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Walter Würzburger, Alexander Schindler, Herman Schaalman, Walter Jacob, Emil Schorsch, Gunther Plaut, and many other future leaders in American Judaism.

The web-based database “German Refugee Rabbis in the United States 1933–1990” was planned and compiled by Cornelia Wilhelm, a professor of Jewish history at the University of Munich. It traces the migration paths and careers of German rabbis who fled to the United States from Nazi Germany after 1933.

The database seeks to complement and expand the scope of existing biographical reference works such as the Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner published by the Steinheim Institute at the University of Essen and the Biographisches Handbuch der deutschsprachigen Emigration, the three-volume joint project of the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich and the Research Foundation for Jewish Immigration.

The database compiles information on the complex trans-national lives of this Jewish leadership, both for American and European scholars. It explores the refugee rabbinate’s impact on Judaism and Jewish communities in the United States as well as their travels or returns to post-war Germany. The engagement of refugee rabbis with post-war Germany recently culminated in the founding of a new liberal rabbinical college, the Abraham Geiger Kolleg, which is the first of its kind since 1933, and a Jewish School of Theology at the University of Potsdam. This new institution finally puts the “Wissenschaft des Judentums” and the academic study of modern Jewish theology on equal footing with Christian theology in Germany, as Abraham Geiger had already demanded in the 19th century.

Besides providing detail on the biographies of the rabbis in an interactive map, the database also makes available resources for further research on this group on both sides of the Atlantic by providing information on archival resources, library materials, and links to digital collections and oral history interviews. Many of these rabbis left papers in the Leo Baeck Institute archives, and LBI collections figure prominently in the linked sources. A monograph by Cornelia Wilhelm is forthcoming.