Between Two Nations

Jews and the 1921 Upper Silesian Plebiscite

- Author

- Agata Sobczak

- Date

- Fri, May 1, 2020

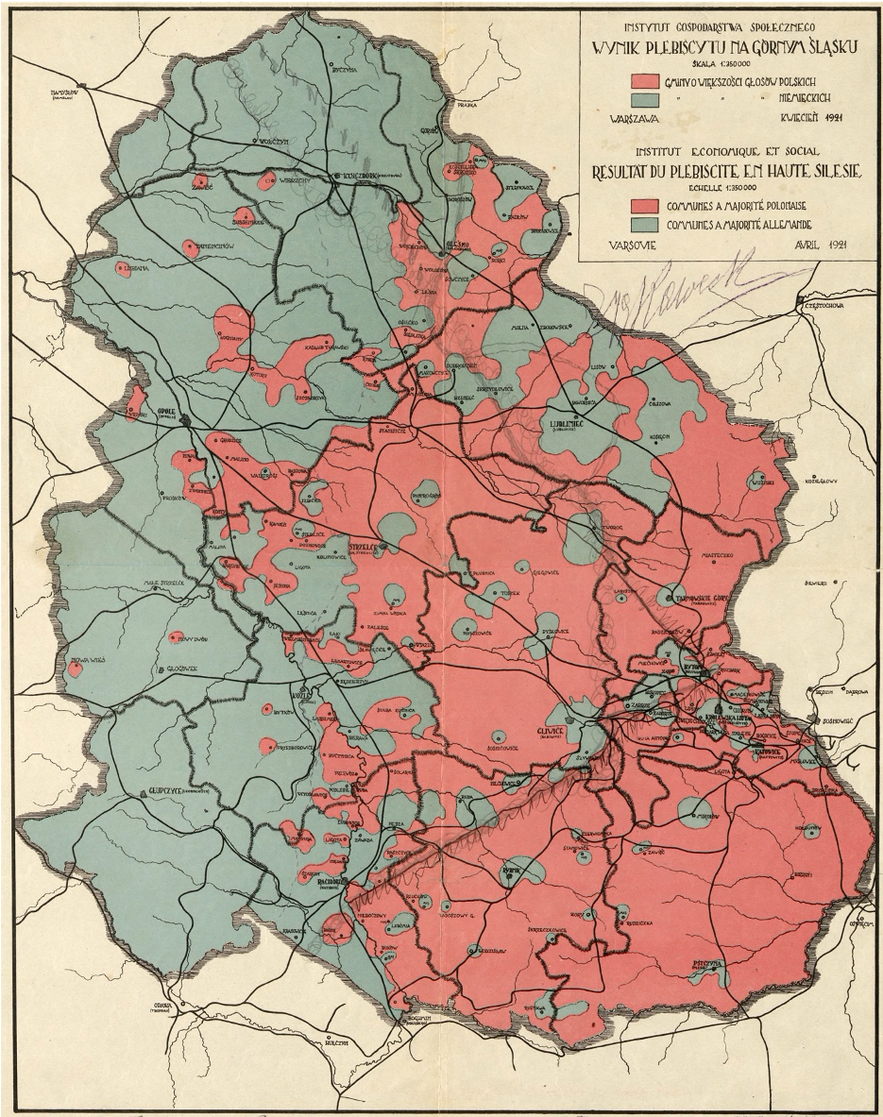

Just as World War I was winding down, Upper Silesia, a Polish-German borderland, was set ablaze by ethnic violence that threatened to tear apart the population. The tensions were exacerbated by unstable border politics with both Germany and a newly reestablished Poland claiming its right to the land. In an effort to resolve the issue, the League of Nations outlined in Article 88 of the Treaty of Versailles that in 1921 a plebiscite was to take place in the region to determine its national belonging. Despite this measure, violence in the region escalated into three armed conflicts (1919,1920,1921) and an extensive propaganda war. The Jewish population found itself caught between the two sides in the lead up to the plebiscite, as both Polish and German nationalists scapegoated Jews for the conflict in the region.

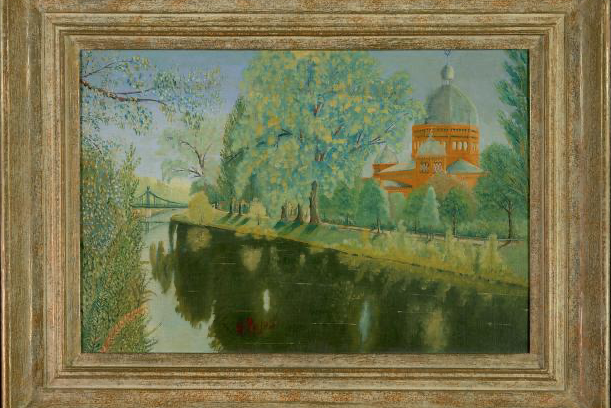

Landscape with view of Synagogue at Oppeln painted by G. Pujas offers the viewer a rare glimpse at the peaceful moments amidst the chaos of everyday life in interwar Upper Silesia. The predominant feature of the painting is the Oppeln Synagogue built in 1893–1897 by the renowned Breslau architect Felix Henry. The synagogue was the center of religious life in the city. It was here that Rabbi Leo Baeck published his famous work Das Wesen des Judentums in 1905. Yet, in the context of the 1921 plebiscite, the painting of the Oppeln Synagogue serves as more than a mere laude to the architectural accomplishments of the Oppeln Jews. It sheds light on the complicated and often violent attempts at manufacturing national identity in nationally ambiguous Upper Silesia.

Upper Silesia has a long and complicated history, having been ruled by a myriad of duchies, kingdoms, and nations each with different languages and customs. In turn, Upper Silesians formed a strong regional identity which manifested itself in unique dialects and cultural traditions. The strong regional identity shunned strict national loyalty. This ambivalence towards national identity became problematic with the approaching of the 1921 plebiscite. Groups of local nationalists supplemented by nationalists from Poland and Germany sought to “awaken” national identity within the Upper Silesians. Nationalist groups and organizations used radical measures to force the population to choose a side. One such measure was the use of antisemitism, which served as a political tool to create a perceived Jewish threat that could unite the population under nationalist banners by refashioning old anti-Jewish stereotypes.

Polish and German nationalist newspapers and other print media portrayed Jews in Upper Silesia as national outsiders who had no ties to where they lived and the land they resided on. A 1919 article in “Górnoślązak” (The Upper Silesian) laments, “And the Jew is a German when he needs it, and a Pole when he wants to, because the Jews speak both languages, but the Jew won’t let anyone look into his Jewish heart.”[1] The alleged ambiguity of Jews was meant to serve as a warning to the Upper Silesians that they must “awaken” the national identity within them and not be like the Jews. The hostile portrayals of Jews as nationally ambiguous outsiders is far removed from the reality of 1920s Upper Silesia. Many Jews fought and died for both sides in the border conflict. Just like other groups, many Jews may have felt ambiguous about their own national identity and remained unconvinced by nationalist propaganda.

The hostile image of the Jews in the contemporary local media is contrasted by Pujas’ painting. Even at the height of ethnic tensions, Pujas presented the synagogue as an integral part of the Upper Silesian cultural and religious landscape, contradicting the narrative put forth by the nationalists. The Jewish community, faced with persecution, persevered through the division of Upper Silesia between Poland and Germany following the mixed results of the 1921 plebiscite, with Oppeln remaining under German rule. However, the resolution of the Polish-German border conflict did not bring peace to the region’s Jews. They remained a target of nationalist hate with the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. In November 1938, the Oppeln synagogue—which once stood proudly on the banks of the Oder River—was set on fire and destroyed as part of the Kristallnacht pogroms. Following the destruction of the synagogue, the number of Oppeln Jews declined drastically, with many choosing to emigrate from Germany. The community was annihilated during the war and failed to rebuild in Oppeln. After 1945, the city of Oppeln (now Opole) became part of Poland. Virtually all traces of its former Jewish inhabitants were erased.

Where the Oppeln synagogue once stood a memorial now bears the words: “They set your temple on fire. Here stood a synagogue burned down by the Nazis during the Kristallnacht on November 9, 1938. People will not forget it.” The synagogue of Oppeln was one of many synagogues destroyed during the Kristallnacht in Upper Silesia and the violence that followed. However, in recent years local organizations in Upper Silesia have put in a great deal of effort to safeguard the legacy of German Jews, including the Upper Silesian Jews House of Remembrance in Gliwice. The House of Remembrance, a 1903 funeral home designed by Max Fleischer, now serves as a museum dedicated to the history of the region’s Jews. Steps are slowly being taken by Polish communities to recognize their shared history with those inhabitants, both Jewish and German, of the region and to reckon with the complicated past of Upper Silesia.

[1] Józef Palędzik, ed., “Wiadomości z bliższych i dalszych stron: Katowice - Mysłowice. (Cygaństwa niemieckie)” Głos Śląskie, Nr. 60- May 20, 1919; Górnoślązak, Nr- 113, May 20, 1919.