Learn your Alef-Bet

The influence of Zionism in German-Jewish children's books

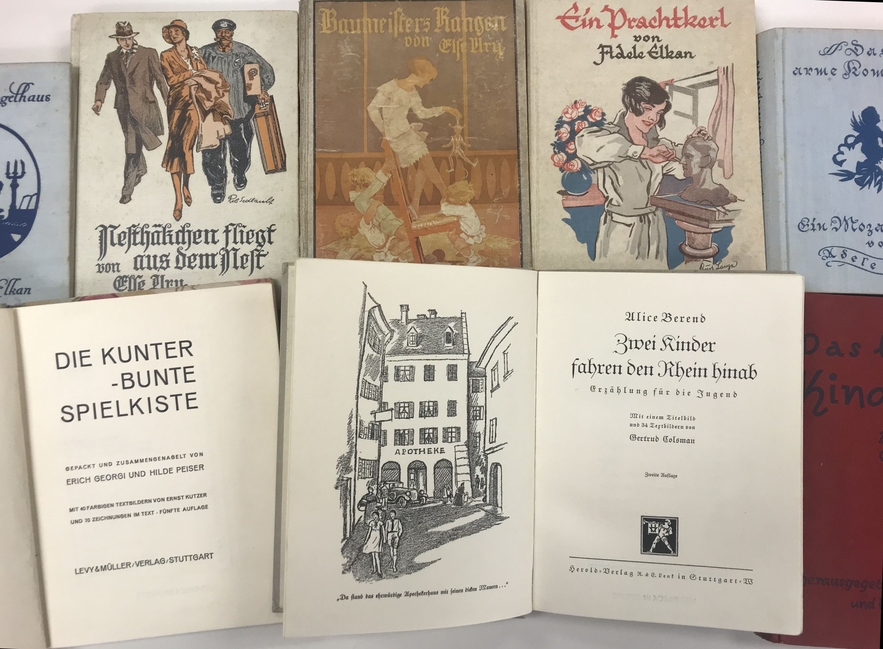

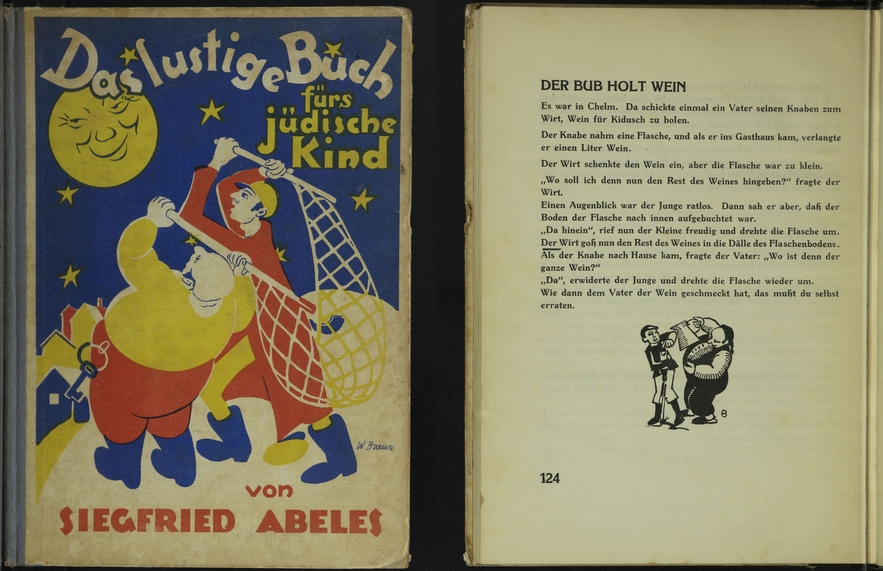

In the early 20th century, authors and publishers of Jewish descent held significant roles in the German children's books industry. Prominent writers like Else Ury, Alice Berend, and Adele Elkan wrote children's novels that were published in numerous editions and printings. Else Ury's Nesthäkchen series about Annemarie Braun, the lively youngest child of a middle-class doctor’s family, is probably the most well-known; the first volume of the series, Nesthäkchen und ihre Puppen (“Nesthäkchen and her dolls”), reached a print run of over 300,000. Children's book publishing firms such as Levy & Müller had Jewish owners, and printed story collections of both Jewish and non-Jewish authors.

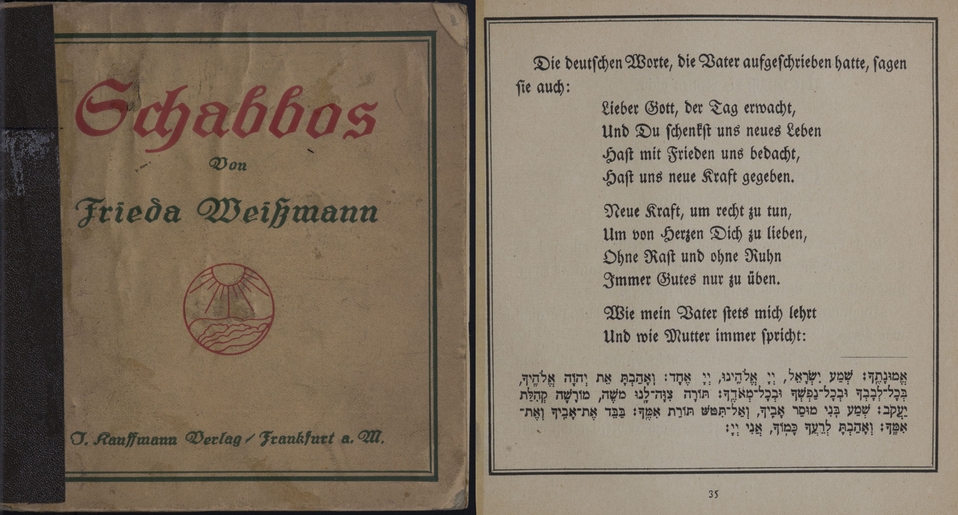

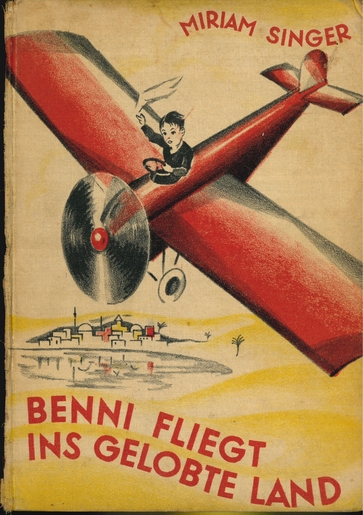

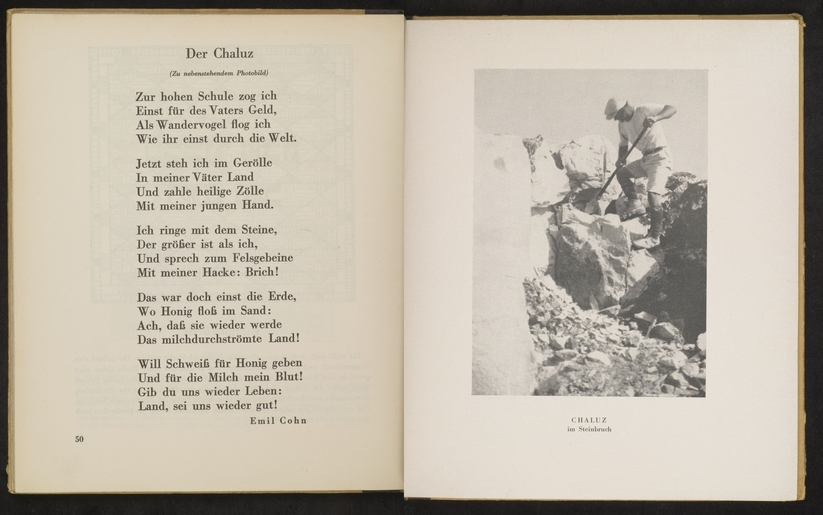

Beginning in the 1930s, Zionism's influence grew in German and Austrian books written specifically for Jewish children. Earlier in the 20th century, books for German-Jewish children had often stressed a German identity as well as a Jewish one. However, as antisemitism grew in Germany and Europe, Jewish children's books presented Palestine increasingly as a natural Jewish homeland. At first, Palestine was only portrayed in children’s literature as a home for some point in the future. As the safety and well-being of German and Austrian youths was threatened by National Socialism, children’s literature began encouraging settlement in Palestine.

Parallel to the influence of Zionism on children’s literature was a rise in Hebrew-language texts for children to prepare them for immigration. In the late 19th century, Hebrew texts for children usually were grammars or readers, often published with parallel German text, and meant as an aid in language-learning for Bible study and other religious purposes. As Jewish children’s education emphasized German identity first, the rigorous study of Hebrew declined.

At the turn of the 20th century, Hebrew literature for children underwent a change as Hebrew education began a national revival. Societies and organizations were founded to help spread Zionism and the Hebrew language. Many had the goal of transforming Hebrew from a literary language to a spoken language. Schools were developed and books for children were published to help teach Hebrew to aid in the preparation for immigration.

Below are some highlights of the Hebrew children's books.

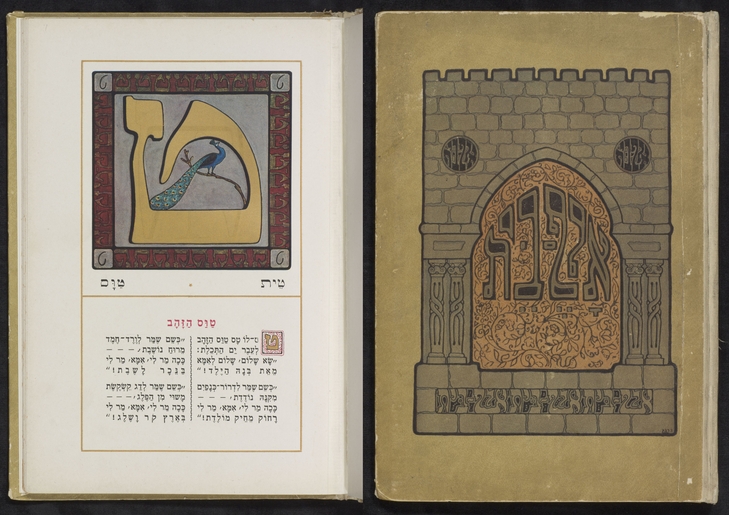

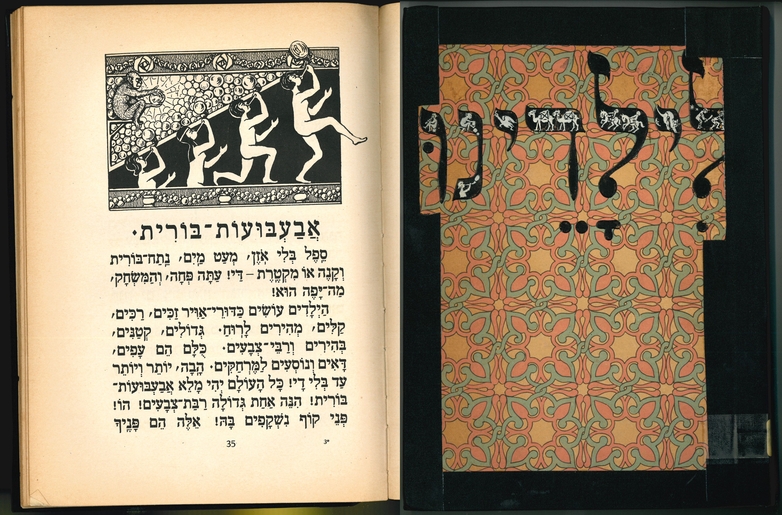

Alef bet by Levin Kipnis and Ze'ev Raban (Berlin : Hotsaʼat "ha-Sefer", 1923. LBI Library, r 537) was a children's Hebrew alphabet book and reader. In 1923, Russian-born Israeli Levin Kipnis, alongside illustrator Ze'ev Raban, created this Hebrew alphabet reader. First printed in Berlin, it served the purpose of teaching Hebrew to the Jewish children of Europe. Kipnis, a poet as well as a writer, dedicated his life to children's causes, publishing hundreds of story and song collections such as this reader. The artist behind the beautiful illustrations in the book was Ze'ev Raban, a founder of the Bezalel school art movement and the Israeli art world as a whole.

The reader itself was structured with small alliterative rhyming poems accompanying each Hebrew letter. Each letter was gilded with detailed illustration of items starting with the same letter surrounding it. For example, the letter "מ" (mem) was shown with a menorah (מנורה).

Both fervent Zionists, Kipnis and Raban infused their alphabet book with Israeli iconography such as camels, palm trees, and pomegranates. Kipnis and Raban were Olim (Israeli immigrants) and included messages encouraging their readers to make aliyah (immigration to Israel).

Lijeladenu (Leipzig : Kaufmann, 1921. LBI Library, PJ 5053 V6 L5), meaning "for our children," was a Hebrew reader of fables written by Mojzis Woskin-Nahartabi and illustrated by the medical doctor Raphel Chamizer. Woskin-Nahartabi was the founder of the first Hebrew private school in German, "Techijja,," located in Leipzig. The school taught both adults and children. Its kindergarten was influential in its use of the Montessori method as its pedagogical model. Woskin-Nahartabi was a pioneer in the spread of New Hebrew in Germany. After 1933, "Techijja" ran an intensive Hebrew evening course for adults in preparation for immigration to Palestine. During the period of National Socialism, the Ukrainian-born Woskin-Nahartabi was forced to leave his position in Leipzig. He eventually relocated to Prague with his family, where they resided until they were deported to Theresienstadt. While in Theresienstadt, he continued to teach Hebrew. He also worked with an elite group of 40 scholars known as the "Talmudkommando" or "Talmud unit" forced to catalog and prepare Nazi looted books. In October 1944, he and his family were deported and murdered in Auschwitz.

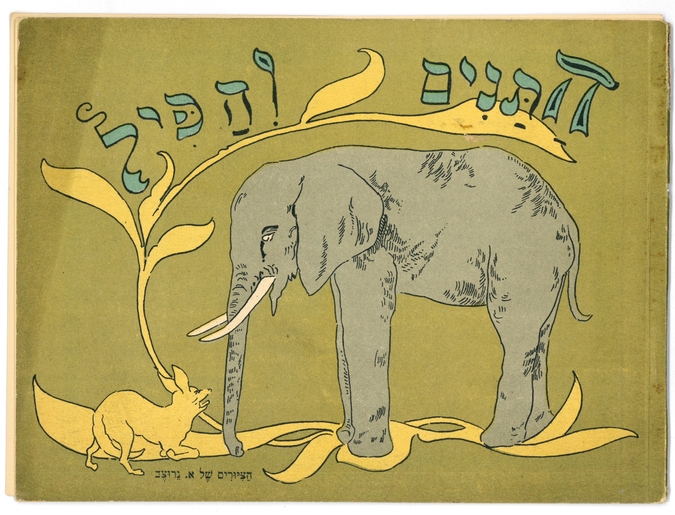

Ha-Tanim ṿeha-pil ("The jackals and the elephant," Franḳfurṭ a.N. Main : Omanut, [1922?]. LBI Library, r 1095) was a children's fable written by Leo Tolstoy and translated into Hebrew. The book's publisher, Omanuth Verlag, was founded in Moscow by Shoshanah Persitz and her father Hilel Zaltopolski, but then newly founded in Frankfurt in 1920. Omanuth published largely Hebrew children's book, especially pedagogical texts. They later relocated to Tel Aviv. It was one the most important publishers for Hebrew texts for a long time.

The advent of the Holocaust brought this chapter of children’s book publishing to a heartbreaking close. Like many Jewish-owned businesses, the publishing house of Levy & Müller was "aryanized." Many authors, like Alice Berend, were forced to emigrate. Others, like Else Ury and Adele Elkan, were both murdered in the Holocaust. However, a new generation of authors who left Germany and Austria as refugees – authors like Doris Orgel and Judith Kerr – grew up to write their own stories for children.

Bibliography:

Grieb, Wolfgang. "Israel - Land der Jugend : "Wir kehren zurück und bauen auf." Jüdisches Kinderleben im Spiegel jüdischer Kinderbücher. Oldenberg, Bibliotheks- und Informationssystem der Universität Oldenburg, 1998. Pages 125-135.

Hinz, Renate and Wilhelm Topsch. "Jüdische Grundschulbücher aus drei Jahrhunderten." Jüdisches Kinderleben im Spiegel jüdischer Kinderbücher. Oldenberg, Bibliotheks- und Informationssystem der Universität Oldenburg, 1998. Pages 167-187

Heitzenröder, Reinhard and Helge-Ulrike Hyams. "Die Bedeutung der hebräischen Sprache für das jüdischen Kind." Jüdisches Kinderleben im Spiegel jüdischer Kinderbücher. Oldenberg, Bibliotheks- und Informationssystem der Universität Oldenburg, 1998. Pages 245-251.

Kowalzik, Barbara. Lehrerbuch : die Lehrer und Lehrerinnen des Leipziger jüdischen Schulwerks 1912-1942. Leipzig : Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2006.

Shavit, Zohar and Hans-Heino Ewers. Deutsche-jüdische Kinder- und Jugendliterature von der Haskala bis 1945. Stuttgart : Verlag J.B. Metzler, 1996.