High Holidays in LBI collections

Rosh Ha-Shanah and Yom Kippur

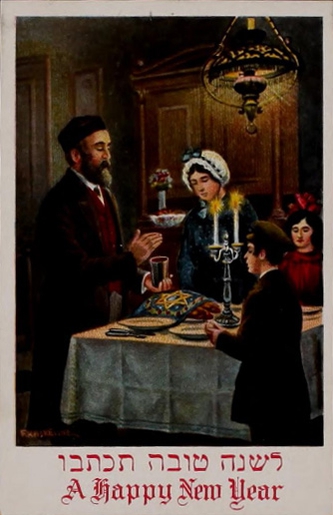

Postcard with a picture of a Jewish family celebrating Rosh Hashanah.

LBI call number: AR 4554.

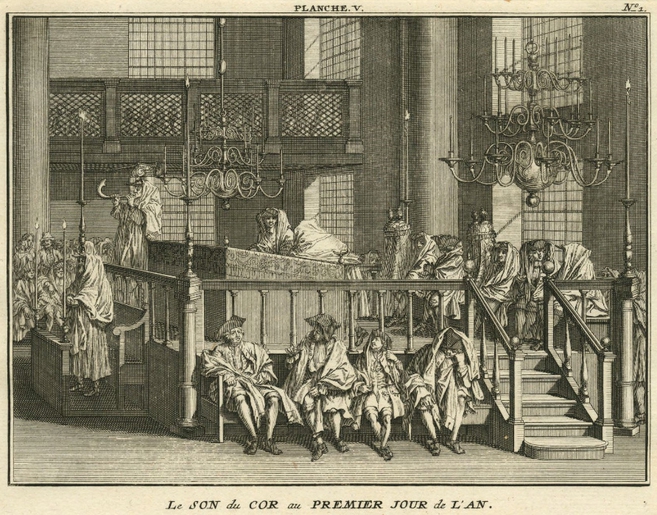

Engraving by Bernard Picart in: "Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde", Amsterdam, 1723-1743.

LBI call number 78.65e.

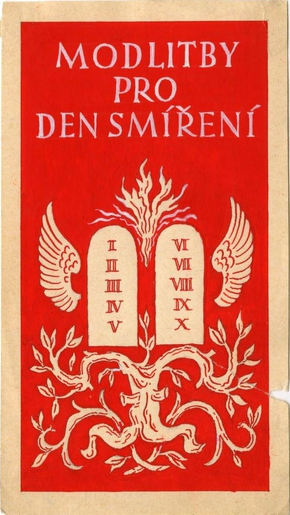

Front page of a Czech prayer book designed by Hugo Steiner-Prag (1880-1945), 1936.

LBI call number 80.199.

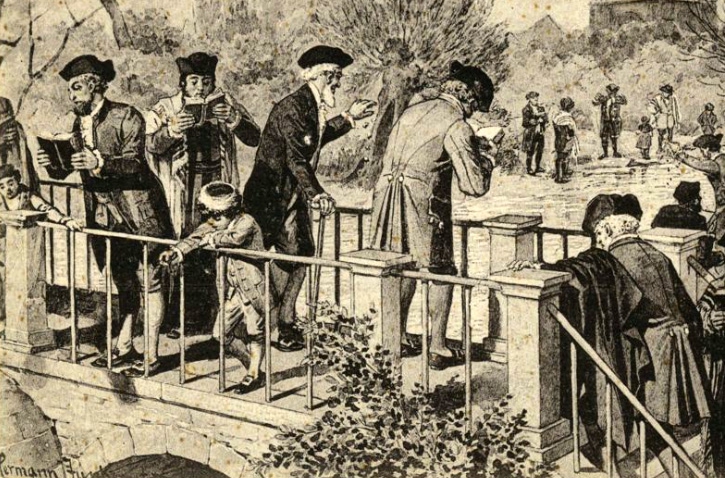

Engraving by Bernard Picart in: "Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde", Amsterdam, 1723-1743.

LBI call number 78.65e.

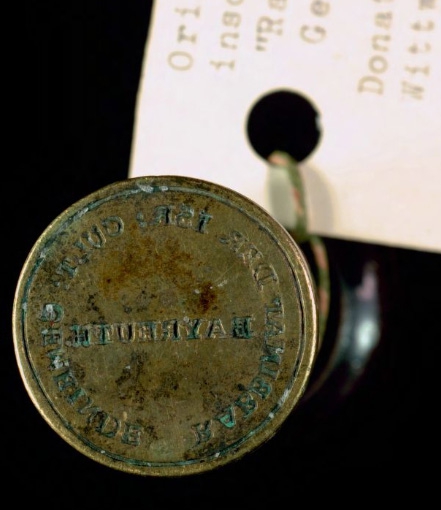

A Yemenite-style shofar from the horn of a kudu, a type of antelope.

LBI call number 2019.07.

Plate no. 8 in a lithograph album by Wilhelm Thielmann.

LBI call number 78.1834h.

The High Holidays

Judaism’s High Holidays – the New Year, Rosh HaShanah, and the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur – are traditionally widely observed by many Jews all over the world. The Leo Baeck Institute holds a myriad of published and unpublished materials reaching back to the first half of the 19th century. They all explain, interpret and illustrate these two holidays through prayer books; liturgy; sermons; photographs; works of art and many other documents.

Rosh Ha-Shanah

The names of those who will live through the coming year are inscribed in the Book of Life!

Rosh Ha-Shanah is the Jewish New Year and the first of the High Holidays. It falls on the first - and outside of Israel, also on the second day of the Hebrew month Tishrei, which overlaps with the months of September and October in the Gregorian calendar.

There are actually four different days known as “New Years” in the Talmud. The Torah places the beginning of the year in springtime, in the Hebrew month of Nissan, but only the first day of the month of Tishrei is known as the “Birthday of the World”.

The most prominent observance of the day is the blowing of the shofar. A shofar is traditionally a ram’s horn, although several other species’ horns may be used. The horn is blown like a brass instrument several times throughout the synagogue service on the holiday in a set pattern of blasts that has been passed down since antiquity. The Torah refers to Rosh Ha-Shanah as Yom Teruah, the Day of Blasting, underlining the day’s principal Mitzvah, or commandment. It is said that the shofar is blown many more times than required by the Torah in order to “confuse the Satan” who stands as an accuser against the children of Israel before the Heavenly Court.

Other traditional observances include eating symbolic foods to help set a tone for our hopes for the coming year. The eating of apples with honey to induce a sweet year is well known. Challah loaves are usually made in a round shape to symbolize the cycle of the year. Some people have the custom of eating the head of a fish to express the desire that we should be the “head” this year and not the “tail.” There are also traditions to consume pomegranates, dates, peas, leeks, spinach, beets, gourds, dates, and many other foods.

The synagogue service is solemn and introspective. The major themes are repentance and Divine Kingship. It is said that on Rosh Ha-Shanah the Book of Life is opened and in it are inscribed the names of those who will live through the coming year. The service contains many special Piyyutim, liturgical poems, that were composed specifically for Rosh Ha-Shanah and the High Holiday season. Extra blessings relating to the Divine Kingship, remembrance, and the sounding of the shofar are included in Rosh Ha-Shanah’s Mussaf service - the additional set of prayers added on special days.

After services, there is the custom of Tashlikh: Jews go to a body of water and cast their sins into the depths. Many people use pieces of bread to represent the sins they are throwing away and commit to overcome.

Yom Kippur

The Book of Life with the names of those who will live through the coming year is sealed!

Yom Kippur - the tenth day of the month of Tishrei - is the Jewish Day of Atonement and the holiest day of the Hebrew calendar. The primary observance of the day is fasting from one evening to the next for the full twenty-five hour (!) duration of the holiday. Fasting involves abstaining completely from food and drink; also forbidden are wearing leather, washing one’s self, anointing with perfumes or lotions, and engaging in marital intimacy. During services, it is customary for married, Ashkenazi men to wear a type of burial garment known as a Kittl or a Sargenes.

Yom Kippur concludes an intense ten-day period of penitence and introspection that began on Rosh Ha-Shanah. While it is said that the names are inscribed in the Book of Life according to their fate on Rosh Ha-Shanah, this fate is sealed on Yom Kippur. It is repeated in the High Holiday liturgy that repentance, prayer, and charity can reverse a bad decree against a person. From Rosh Ha-Shanah until the end of Yom Kippur, a major emphasis is placed on looking within and working hard to improve one’s behavior.

Prior to the evening service on the night of Yom Kippur, a passage in the form of an Aramaic legal statement is chanted. This passage, known as Kol Nidrei, absolves all vows the congregants have taken upon themselves, but find themselves unable or unwilling to sustain. While Kol Nidrei does not undo vows made to another person, it releases one from personal oaths made before the divine. To begin Yom Kippur in this way is to provide a clean slate on promises made to the self and G-d and to clear the way for an intense day of self-examination.

One very moving part of the day’s liturgy describes the service of the High Priest on Yom Kippur in the days when the Temples stood in Jerusalem. The Priest’s service included many ritual immersions and sacrifices, but it all culminated in one grand event. The High Priest would enter the Holy of Holies and speak the explicit Name of G-d aloud. If he and the Israelites were deemed fit, the Priest would emerge in peace with a radiant countenance and the nation would be considered absolved of its sins.

The Yom Kippur liturgy concludes with the Neilah service that includes numerous Piyyutim - liturgical poems - on the subject of repentance and awe of the divine. At the end of the Neilah service, the shofar is blown, and the weary and hungry congregants are released to their break-fast, hopefully a little wiser and ready to take on the challenges of the year ahead.

Text by Karel Teifer