What’s in a Name? Dennis Baum and the Simson Company

- Autor

- David Brown

- Datum

- Sa., 1. Mär. 2014

Dennis Baum fought for restitution of his family’s assets in Germany for years following German reunification in 1990. In January, Baum joined his former negotiating partners in a public forum at the Jewish Museum Berlin to discuss what went wrong 20 years ago. The records of the Simson Company and the case of its restitution through the Treuhandanstalt are now preserved in the LBI Archives.

In Germany, the name Simson is remembered primarily as the East German manufacturer of a utilitarian moped called the Schwalbe. Like other brands made ubiquitous by the dictates of socialist economic planners (from the Trabi sedan to Halberstädter sausages) it endeared itself to East Germans not so much for its elegant design, quality, or reliability, but because it was one of very few choices for two-wheeled freedom on the market. Although they are no longer manufactured, used Schwalbe scooters are still hotly desired by a cult following of GDRnostalgists and grease-stained tinkerers.

In the United States, Simson is less of a household name, but it inspires similar fervor among historic firearms enthusiasts. Simson-Suhl hunting rifles with intricate engravings of game birds in flight and stags in the woods fetch much higher prices than their two-wheeled cousins, up to $10,000 for the right make and year.

For Dennis Baum, a New York investment manager who has been an LBI trustee since 2009, Simson was first and foremost the maiden name of his grandmother, Minna, who came to the US from Germany in 1936. “The family rarely discussed the assets we had left behind in Germany,” said Baum, “I knew vaguely that there had been a company that produced cars at some point.”

In the spring of 1990, traveling down pot-holed East German roads to his family’s former hometown of Suhl in Thuringia, he saw his first clue that the Simson name meant more than he realized. “We were stuck behind a bus, and on the back of the bus was an ad for a Roller, which is a scooter, basically, called the Simson-Schwalbe.”

A mark of quality—from guns to bicycles

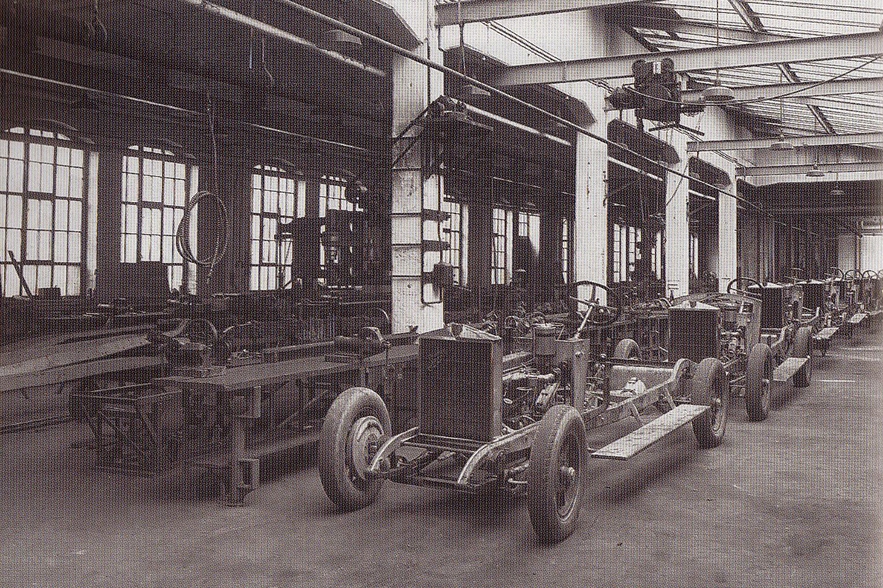

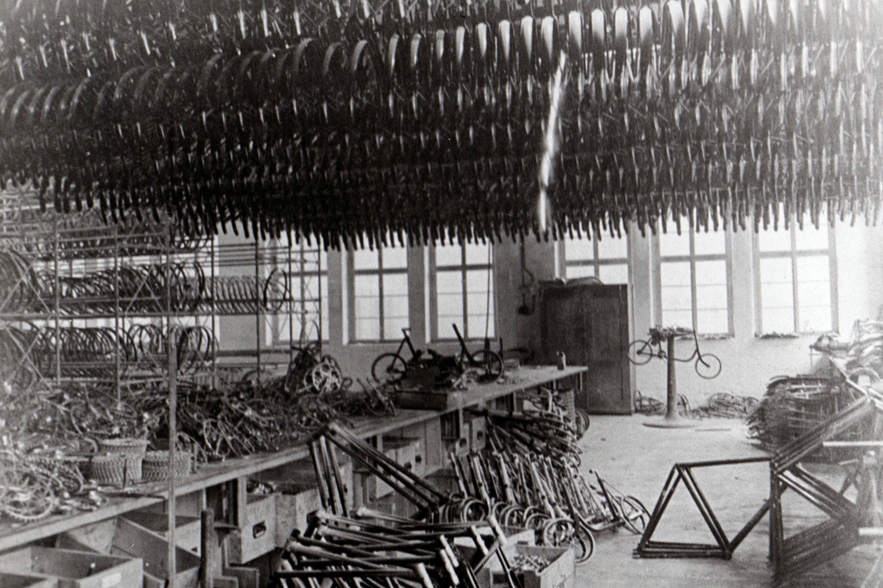

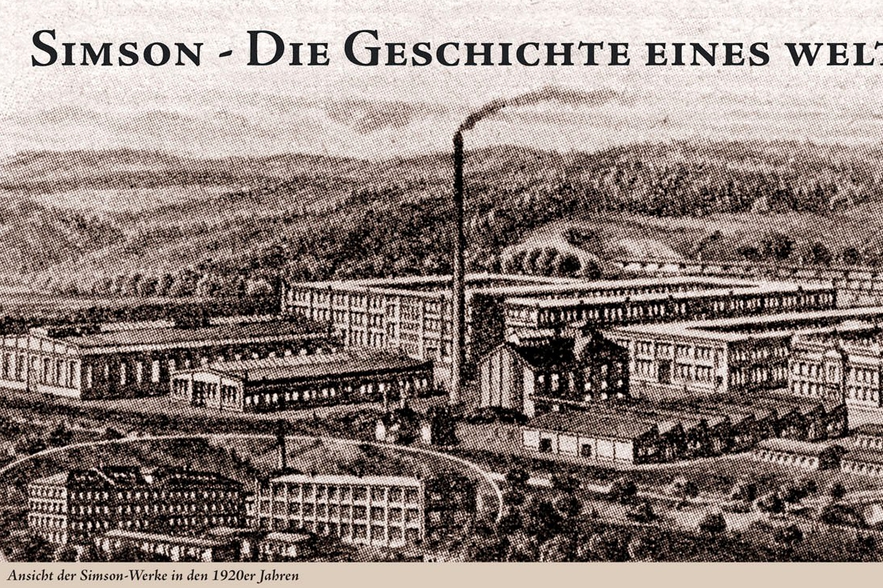

Baum would learn that the assets his family could claim as the rightful heirs to a business founded by two Jewish brothers in 1856 encompassed around 500 properties in the former GDR. Part of the first generation of Jews in Prussia that could own property, Moses and Löb Simson purchased a steel forge in Suhl, a region that had produced armaments since the 15th century. By the time Moses’s grandsons Arthur and Julius Simson took over management of the company in the early 1920’s, they oversaw the largest workforce in Suhl, which produced an array of firearms, bicycles, automobiles, and even engines for aircraft.

By branching out into civilian products, the Simson family had shielded its company from the boom and bust cycles of an armaments market driven by state contracts. In the de-militarized Weimar republic, however, Simson & Co. received the exclusive license to produce weapons for the Reichswehr. This monopoly proved as dangerous as it was lucrative, tying the business to a weak government in a volatile political environment.

Although the Reichswehr contract allowed the business to weather the economic cataclysm of 1929, the company’s success was fodder for anti-Semitic propaganda against the “Jewish monopoly.” Various stakeholders had an interest in the future of Germany’s only arms builder, but one local Nazi functionary named Fritz Sauckel made the company a target of a very personal crusade. As early as 1927, Sauckel published an editorial in Der National-Sozialist claiming that the company had billed the Reichswehr for costs related to its civilian products. His opening salvo against the family was based on the absurd premise that workers kept gun parts under their workbenches as they built bicycles, which they would swap out at short notice to deceive military inspectors.

It was the first of a series of scurrilous claims that came to a head at the Gestapo headquarters on Prinz-Albrecht-Straße in Berlin on November 23, 1935. In the nerve center of the Nazi terror apparatus, Arthur Simson was forced to sign a contract transferring control of the company to Sauckel. The “Sales Agreement” included no compensation for the Simson family; the value of the company was offset by a penalty for “excess profits” allegedly skimmed off the Reichswehr orders. Stripped of their family’s business, Arthur and Julius Simson joined their siblings, including Dennis Baum’s grandmother Minna, in the United States.

Fight for restitution

That was not the last time the Simson company would change hands. After WWII, the former Simson factories became property of the Soviet occupiers. Later, they were returned to the workers of the GDR, who built mopeds and hunting rifles there in massive, vertically integrated Kombinate and Volkseigene Betriebe.

Though the circumstances of production had changed, the Simson brand was still a mark of quality. Arthur Simson granted permission for the East German successor companies to keep using the Simson brand name over the phone in the 1970s. “I think that was one of Arthur Simson’s smartest decisions,” said Baum. “He sensed that the name strengthened the family’s claim to the company.”

After German reunification, the companies passed into the control of the Treuhandanstalt, a government trust charged with privatizing the entire economy of the former German Democratic Republic in short order. That meant breaking up the massive socialist conglomerates and selling them to private investors.

Before they could be sold, however, the question of reparations or restitution for expropriated owners had to be settled, a mammoth task given the company’s history. “Every asset was a different story,” says Baum, “we’re talking about villas, villages, and even one Schrebergarten, these tiny plots of land where Germans grow vegetables.”

As they negotiated for hundreds of assets, Baum stresses that the heirs took pains to be fair in their dealings, especially since many of the restituted properties involved people’s homes.

In one case, however, they saw a business opportunity. The family believed that the Suhler Jagd- und Sportwaffen GmbH (Suhl Hunting and Sports Weapons – JuS GmbH) was a brand they could build on.

The company had built the precision rifles that East German biathletes used to bring home Olympic gold. The Simson heirs enlisted a team that included the late J. Thompson Ruger, the scion of a leading family of American gunsmiths, to get the new company off the ground with a marketing campaign built on the firm’s former Olympic prowess. “Tom’s forte was marketing,” said Baum, “he was a kind of man’s man—the one who went hunting and shooting with all the buyers.” Those buyers worked for some of the largest gun retailers in the United States—national chains like Kmart, Walmart, and Sears. The Simson heirs proposed a joint venture with the Sturm-Ruger company. They would invest the reparations they received from the defunct moped business to acquire and rebuild the hunting rifle business and bring (East-)German engineering to the deer and duck blinds of the American heartland.

The heirs to the Jewish family that built one of the largest businesses in Thuringia were poised to make a symbolic return to their hometown in a reunited Germany, building the same products that had driven the region’s economy for centuries. They wanted to give a traditional industry in one of the new German states a much-needed infusion of expertise and entrepreneurial vigor just as its former markets in the Soviet Bloc were collapsing.

Instead, the Simson heirs were excluded from the bidding process in 1992, and the JuS GmbH was awarded to a DutchFrench consortium for 27 million DM. The investment funds never materialized, JuS GmbH went bankrupt within a year, and today only a tiny number of gunsmiths still work in Suhl. The Simson heirs received monetary reparations for their assets, but their emotional investment in making a return to their roots in Germany never bore fruit.

Twenty years later, a discussion

“We privatized thousands of companies in a span of four years. A normal investment bank would do two or three per year if they are doing a professional job,” said Detlev Scheunert on January 23, 2014 at the Jewish Museum in Berlin. As the youngest department manager at the Treuhandanstalt and the only one from the former East Germany, Scheunert had sat across the negotiating table from Baum and the Simson family attorneys in the early 1990s.

Twenty years later, he was once again at a table with Dennis Baum and other key players in the Simson restitution case, this time at the Jewish Museum Berlin for an unusually candid public forum to present each side’s perspective.

Scheunert described how political considerations created a compressed time-frame for the Treuhand that left little room for the complex legal, ethical, and emotional issues of restitution. In addition to the limited tolerance of allies like France and the UK for a protracted German unification process, the concerns of West-German taxpayers had to be neutralized. “[Chancellor Helmut] Kohl was a campaigner,” said Scheunert, “there was an election in 1990 and an election in 1994, so that set the timeframe for us.”

As it became clear that “privatization” usually meant shuttered factories and lost jobs, the Treuhand became deeply unpopular among former East Germans. As one of the only Easterners in an agency that was viewed as the wrecking crew for the East German economy, Scheunert paid a social price. “It wasn’t fun to come to work and see how workers were smashing up your car with poles,” he said.

Asked whether he might act differently today, however, Scheunert suggested that the narrow mission of the Treuhand wouldn’t have permitted any other result. “It was very difficult to thread the Simson case through the needle that was ‘privatization by the Treuhand.’ ” As a result, the family’s history in the region played no role in the decision on their bid. “There were very clear criteria,” said Scheunert, “We had a questionnaire with 70 questions and 11 signatures.”

Herbert Warth, a German consultant who was hired by the Simson heirs to conduct research and then became their business partner, argued that while the criteria may have been clear, they weren’t the right ones. “The Treuhand’s job should have been to secure jobs,” said Warth, “the decisive question was, ‘who can sell this many hunting rifles?’ Maybe the other bidders offered more cash, but they had no chance.”

One reason that the facts of the case remain the subject of such intense debate even 20 years later is that the files of the Treuhandanstalt have been sealed. “I was one-sided in my presentation because I only had documents from the Simson side,” said Ulrike Schulz, a historian at the University of Bielefeld who wrote a history of the company in 2013. “Historians will have to play an arduous game of catch-up to present a complete picture of this chapter in German history.”

Although the Treuhand’s files will not be fully opened until 2050, the documentation collected by Herbert Warth’s team will be preserved and made public in its entirety at the LBI archives. That, and discussions like this one at the Jewish Museum Berlin, will make this history—of the German Jews, German unification, restitution, and the myriad ways they still intersect—that much richer.

And, as Ulrike Schulz noted hopefully, the history of Simson is not necessarily over. One of the concessions the heirs did win from the Treuhand was the rights to the Simson brand name. “So, if an investor wants to resurrect moped production in Suhl again under the Simson name, they can call Dennis Baum and ask him.”

LITERATURE

Schulz, Ulrike. Simson: Vom unwahrscheinlichen Überleben eines Unternehmens 1856–1993. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2013.

Aktuelles